|

Thai script

The Thai script (Thai: อักษรไทย, RTGS: akson thai, pronounced [ʔàksɔ̌ːn tʰāj]) is the abugida used to write Thai, Southern Thai and many other languages spoken in Thailand. The Thai script itself (as used to write Thai) has 44 consonant symbols (Thai: พยัญชนะ, phayanchana), 16 vowel symbols (Thai: สระ, sara) that combine into at least 32 vowel forms, four tone diacritics (Thai: วรรณยุกต์ or วรรณยุต, wannayuk or wannayut), and other diacritics. Although commonly referred to as the Thai alphabet, the script is not a true alphabet but an abugida, a writing system in which the full characters represent consonants with diacritical marks for vowels; the absence of a vowel diacritic gives an implied 'a' or 'o'. Consonants are written horizontally from left to right, and vowels following a consonant in speech are written above, below, to the left or to the right of it, or a combination of those. History  The Thai script is derived from the Sukhothai script, which itself is derived from the Old Khmer script (Thai: อักษรขอม, akson khom), which is a southern Brahmic style of writing derived from the south Indian Pallava alphabet (Thai: ปัลลวะ). According to tradition it was created in 1283 by King Ram Khamhaeng the Great (Thai: พ่อขุนรามคำแหงมหาราช).[1] The earliest attestation of the Thai script is the Ram Khamhaeng Inscription dated to 1292, however some scholars question its authenticity.[2] The script was derived from a cursive form of the Old Khmer script of the time.[1] It modified and simplified some of the Old Khmer letters and introduced some new ones to accommodate Thai phonology. It also introduced tone marks. Thai is considered to be the first script in the world that invented tone markers to indicate distinctive tones, which are lacking in the Mon-Khmer (Austroasiatic languages), Dravidian languages and Indo-Aryan languages from which its script is derived or partly influenced. Although Chinese and other Sino-Tibetan languages have distinctive tones in their phonological system, no tone marker is found in their orthographies. Thus, tone markers are an innovation in the Thai language that later influenced other related Tai languages and some Tibeto-Burman languages on the Mainland Southeast Asia.[2] Another addition was consonant clusters that were written horizontally and contiguously, rather than writing the second consonant below the first one.[2] Finally, the script wrote vowel marks on the main line, however this innovation fell out of use not long after.[1] Orthography There is a fairly complex relationship between spelling and sound. There are various issues:

Thai letters do not have upper- and lower-case forms like Latin letters do. Spaces between words are not used, except in certain linguistically motivated cases. PunctuationMinor pauses in sentences may be marked by a comma (Thai: จุลภาค or ลูกน้ำ, chunlaphak or luk nam), and major pauses by a period (Thai: มหัพภาค or จุด, mahap phak or chut), but most often are marked by a blank space (Thai: วรรค, wak). Thai writing also uses quotation marks (Thai: อัญประกาศ, anyaprakat) and parentheses (round brackets) (Thai: วงเล็บ, wong lep or Thai: นขลิขิต, nakha likhit), but not square brackets or braces. A paiyan noi ฯ (Thai: ไปยาลน้อย) is used for abbreviation. A paiyan yai ฯลฯ (Thai: ไปยาลใหญ่) is the same as "etc." in English. Several obsolete characters indicated the beginning or ending of sections. A bird's eye ๏ (Thai: ตาไก่, ta kai, officially called ฟองมัน, fong man) formerly indicated paragraphs. An angkhan kuu ๚ (Thai: อังคั่นคู่) was formerly used to mark the end of a chapter. A kho mut ๛ (Thai: โคมูตร) was formerly used to mark the end of a document, but is now obsolete. Alphabet listingThai (along with its sister system, Lao) lacks conjunct consonants and independent vowels, while both designs are common among Brahmic scripts (e.g., Burmese and Balinese).[4] In scripts with conjunct consonants, each consonant has two forms: base and conjoined. Consonant clusters are represented with the two styles of consonants. The two styles may form typographical ligatures, as in Devanagari. Independent vowels are used when a syllable starts with a vowel sign. ConsonantsThere are 44 consonant letters representing 21 distinct consonant sounds. Duplicate consonants either correspond to sounds that existed in Old Thai at the time the alphabet was created but no longer exist (in particular, voiced obstruents such as d), or different Sanskrit and Pali consonants pronounced identically in Thai. There are in addition four consonant-vowel combination characters not included in the tally of 44. Consonants are divided into three classes — in alphabetical order these are middle (กลาง, klang), high (สูง, sung), and low (ต่ำ, tam) class — as shown in the table below. These class designations reflect phonetic qualities of the sounds to which the letters originally corresponded in Old Thai. In particular, "middle" sounds were voiceless unaspirated stops; "high" sounds, voiceless aspirated stops or voiceless fricatives; "low" sounds, voiced. Subsequent sound changes have obscured the phonetic nature of these classes.[nb 1] Today, the class of a consonant without a tone mark, along with the short or long length of the accompanying vowel, determine the base accent (พื้นเสียง, phuen siang). Middle class consonants with a long vowel spell an additional four tones with one of four tone marks over the controlling consonant: mai ek, mai tho, mai tri, and mai chattawa. High and low class consonants are limited to mai ek and mai tho, as shown in the . Differing interpretations of the two marks or their absence allow low class consonants to spell tones not allowed for the corresponding high class consonant. In the case of digraphs where a low class follows a higher class consonant, often the higher class rules apply, but the marker, if used, goes over the low class one; accordingly, ห นำ ho nam and อ นำ o nam may be considered to be digraphs as such, as explained below the Tone table.[nb 2]

To aid learning, each consonant is traditionally associated with an acrophonic Thai word that either starts with the same sound, or features it prominently. For example, the name of the letter ข is kho khai (ข ไข่), in which kho is the sound it represents, and khai (ไข่) is a word which starts with the same sound and means "egg". Two of the consonants, ฃ (kho khuat) and ฅ (kho khon), are no longer used in written Thai, but still appear on many keyboards and in character sets. When the first Thai typewriter was developed by Edwin Hunter McFarland in 1892, there was simply no space for all characters, thus two had to be left out.[5] Also, neither of these two letters correspond to a Sanskrit or Pali letter, and each of them, being a modified form of the letter that precedes it (compare ข and ค), has the same pronunciation and the same consonant class as the preceding letter, thus making them redundant. They used to represent the sound /x/ in Old Thai, but it has merged with /kʰ/ in Modern Thai. Equivalents for romanisation are shown in the table below. Many consonants are pronounced differently at the beginning and at the end of a syllable. The entries in columns initial and final indicate the pronunciation for that consonant in the corresponding positions in a syllable. Where the entry is '-', the consonant may not be used to close a syllable. Where a combination of consonants ends a written syllable, only the first is pronounced; possible closing consonant sounds are limited to 'k', 'm', 'n', 'ng', 'p' and 't'. Although official standards for romanisation are the Royal Thai General System of Transcription (RTGS) defined by the Royal Thai Institute, and the almost identical ISO 11940-2 defined by the International Organization for Standardization, many publications use different romanisation systems. In daily practice, a bewildering variety of romanisations are used, making it difficult to know how to pronounce a word, or to judge if two words (e.g. on a map and a street sign) are actually the same. For more precise information, an equivalent from the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) is given as well. Alphabetic

PhoneticThe consonants can be organised by place and manner of articulation according to principles of the International Phonetic Association. Thai distinguishes among three voice/aspiration patterns for plosive consonants:

Where English has only a distinction between the voiced, unaspirated /b/ and the unvoiced, aspirated /pʰ/, Thai distinguishes a third sound which is neither voiced nor aspirated, which occurs in English only as an allophone of /p/, approximately the sound of the p in "spin". There is similarly a laminal denti-alveolar /t/, /tʰ/, /d/ triplet. In the velar series there is a /k/, /kʰ/ pair and in the postalveolar series the /tɕ/, /tɕʰ/ pair. In each cell below, the first line indicates International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA),[6] the second indicates the Thai characters in initial position (several letters appearing in the same box have identical pronunciation). The conventional alphabetic order shown in the table above follows roughly the table below, reading the coloured blocks from right to left and top to bottom.

Although the overall 44 Thai consonants provide 21 sounds in case of initials, the case for finals is different. The consonant sounds in the table for initials collapse in the table for final sounds. At the end of a syllable, all plosives are unvoiced, unaspirated, and have no audible release. Initial affricates and fricatives become final plosives. The initial trill (ร), approximant (ญ), and lateral approximants (ล, ฬ) are realized as a final nasal /n/. Only 8 ending consonant sounds, as well as no ending consonant sound, are available in Thai pronunciation. Among these consonants, excluding the disused ฃ and ฅ, six (ฉ, ผ, ฝ, ห, อ, ฮ) cannot be used as a final. The remaining 36 are grouped as following.

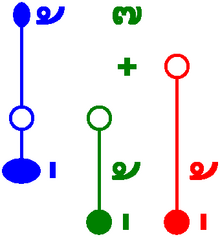

VowelsThai vowel sounds and diphthongs are written using a mixture of vowel symbols on a consonant base. Each vowel is shown in its correct position relative to a base consonant and sometimes a final consonant as well. Vowels can go above, below, left of or right of the consonant, or combinations of these places. If a vowel has parts before and after the initial consonant, and the syllable starts with a consonant cluster, the split will go around the whole cluster. Twenty-one vowel symbol elements are traditionally named, which may appear alone or in combination to form compound symbols.

The inherent vowels are /a/ in open syllables (CV) and /o/ in closed syllables (CVC). For example, ถนน transcribes /tʰànǒn/ "road". There are a few exceptions in Pali loanwords, where the inherent vowel of an open syllable is /ɔː/. The circumfix vowels, such as เ–าะ /ɔʔ/, encompass a preceding consonant with an inherent vowel. For example, /pʰɔʔ/ is written เพาะ, and /tɕʰapʰɔʔ/ "only" is written เฉพาะ. The characters ฤ ฤๅ (plus ฦ ฦๅ, which are obsolete) are usually considered as vowels, the first being a short vowel sound, and the latter, long. The letters are based on vocalic consonants used in Sanskrit, given the one-to-one letter correspondence of Thai to Sanskrit, although the last two letters are quite rare, as their equivalent Sanskrit sounds only occur in a few, ancient words and thus are functionally obsolete in Thai. The first symbol 'ฤ' is common in many Sanskrit and Pali words and 'ฤๅ' less so, but does occur as the primary spelling for the Thai adaptation of Sanskrit 'rishi' and treu (Thai: ตฤๅ /trɯ̄ː/ or /trīː/), a very rare Khmer loan word for 'fish' only found in ancient poetry. As alphabetical entries, ฤ ฤๅ follow ร, and themselves can be read as a combination of consonant and vowel, equivalent to รึ (short), and รือ (long) (and the obsolete pair as ลึ, ลือ), respectively. Moreover, ฤ can act as ริ as an integral part in many words mostly borrowed from Sanskrit such as กฤษณะ (kritsana, not kruetsana), ฤทธิ์ (rit, not ruet), and กฤษดา (kritsada, not kruetsada), for example. It is also used to spell อังกฤษ angkrit England/English. The word ฤกษ์ (roek) is a unique case where ฤ is pronounced like เรอ. In the past, prior to the turn of the twentieth century, it was common for writers to substitute these letters in native vocabulary that contained similar sounds as a shorthand that was acceptable in writing at the time. For example, the conjunction 'or' (Thai: หรือ /rɯ̌ː/ rue, cf. Lao: ຫຼຶ/ຫລື /lɯ̌ː/ lu) was often written Thai: ฤ. This practice has become obsolete, but can still be seen in Thai literature. The pronunciation below is indicated by the International Phonetic Alphabet[6] and the Romanisation according to the Royal Thai Institute as well as several variant Romanisations often encountered. A very approximate equivalent is given for various regions of English speakers and surrounding areas. Dotted circles represent the positions of consonants or consonant clusters. The first one represents the initial consonant and the latter (if it exists) represents the final. Ro han (ร หัน) is not usually considered a vowel and is not included in the following table. It represents the sara a /a/ vowel in certain Sanskrit loanwords and appears as ◌รร◌. When used without a final consonant (◌รร), /n/ is implied as the final consonant, giving /an/.

ToneCentral ThaiThai is a tonal language, and the script gives full information on the tones. Tones are realised in the vowels, but indicated in the script by a combination of the class of the initial consonant (high, mid or low), vowel length (long or short), closing consonant (plosive or sonorant, called dead or live) and, if present, one of four tone marks, whose names derive from the names of the digits 1–4 borrowed from Pali or Sanskrit. The rules for denoting tones are shown in the following chart:

"None", that is, no tone marker, is used with the base accent (พื้นเสียง, phuen siang). Mai tri and mai chattawa are only used with mid-class consonants. Two consonant characters (not diacritics) are used to modify the tone:

In some dialects there are words which are spelled with one tone but pronounced with another and often occur in informal conversation (notably the pronouns ฉัน chan and เขา khao, which are both pronounced with a high tone rather than the rising tone indicated by the script). Generally, when such words are recited or read in public, they are pronounced as spelled. Southern ThaiSpoken Southern Thai can have up to seven tones.[7] When Southern Thai is written in Thai script, there are different rules for indicating spoken tone.

DiacriticsOther diacritics are used to indicate short vowels and silent letters:

Fan nu means "rat teeth" and is thought as being placed in combination with short sara i and fong man to form other characters.

NumeralsFor numerals, mostly the standard Hindu-Arabic numerals (Thai: เลขฮินดูอารบิก, lek hindu arabik) are used, but Thai also has its own set of Thai numerals that are based on the Hindu-Arabic numeral system (Thai: เลขไทย, lek thai), which are mostly limited to government documents, election posters, license plates of military vehicles, and special entry prices for Thai nationals.

Other symbols

Pai-yan noi and angkhan diao share the same character. Sara a (–ะ) used in combination with other characters is called wisanchani. Some of the characters can mark the beginning or end of a sentence, chapter, or episode of a story or of a stanza in a poem. These have changed use over time and are becoming uncommon. Summary charts

colour codes red: dead green: alive

colour codes pink: long vowel, shortened by add "ะ"(no ending consonant) or "-็"(with ending consonant) green: long vowel, has a special form when shortened

Sanskrit and Pali

The Thai script (like all Indic scripts) uses a number of modifications to write Sanskrit and related languages (in particular, Pali). Pali is very closely related to Sanskrit and is the liturgical language of Thai Buddhism. In Thailand, Pali is written and studied using a slightly modified Thai script. The main difference is that each consonant is followed by an implied short a (อะ), not the 'o', or 'ə' of Thai: this short a is never omitted in pronunciation, and if the vowel is not to be pronounced, then a specific symbol must be used, the pinthu อฺ (a solid dot under the consonant). This means that sara a (อะ) is never used when writing Pali, because it is always implied. For example, namo is written นะโม in Thai, but in Pali it is written as นโม, because the อะ is redundant. The Sanskrit word 'mantra' is written มนตร์ in Thai (and therefore pronounced mon), but is written มนฺตฺร in Sanskrit (and therefore pronounced mantra). When writing Pali, only 33 consonants and 12 vowels are used. This is an example of a Pali text written using the Thai Sanskrit orthography: อรหํ สมฺมาสมฺพุทฺโธ ภควา [arahaṃ sammāsambuddho bhagavā]. Written in modern Thai orthography, this becomes อะระหัง สัมมาสัมพุทโธ ภะคะวา arahang sammasamphuttho phakhawa. In Thailand, Sanskrit is read out using the Thai values for all the consonants (so ค is read as kha and not [ga]), which makes Thai spoken Sanskrit incomprehensible to sanskritists not trained in Thailand. The Sanskrit values are used in transliteration (without the diacritics), but these values are never actually used when Sanskrit is read out loud in Thailand. The vowels used in Thai are identical to Sanskrit, with the exception of ฤ, ฤๅ, ฦ, and ฦๅ, which are read using their Thai values, not their Sanskrit values. Sanskrit and Pali are not tonal languages, but in Thailand, the Thai tones are used when reading these languages out loud. In the tables of this section, the Thai value (transliterated according to the Royal Thai system) of each letter is listed first, followed by the IAST value of each letter in square brackets. The IAST values are never used in pronunciation, but sometimes in transcriptions (with the diacritics omitted). This disjoint between transcription and spoken value explains the romanisation for Sanskrit names in Thailand that many foreigners find confusing. For example, สุวรรณภูมิ is romanised as Suvarnabhumi, but pronounced su-wan-na-phum. ศรีนครินทร์ is romanised as Srinagarindra but pronounced si-nakha-rin. Plosives (vargaḥ)Plosives (also called stops) are listed in their traditional Sanskrit order, which corresponds to Thai alphabetical order from ก to ม with three exceptions: in Thai, high-class ข is followed by two obsolete characters with no Sanskrit equivalent, high-class ฃ and low-class ฅ; low-class ช is followed by sibilant ซ (low-class equivalent of high-class sibilant ส that follows ศ and ษ.) The table gives the Thai value first, and then the IAST (International Alphabet of Sanskrit Transliteration) value in square brackets.

None of the Sanskrit plosives are pronounced as the Thai voiced plosives, so these are not represented in the table. While letters are listed here according to their class in Sanskrit, Thai has lost the distinction between many of the consonants. So, while there is a clear distinction between ช and ฌ in Sanskrit, in Thai these two consonants are pronounced identically (including tone). Likewise, the Thai phonemes do not differentiate between the retroflex and dental classes, since Thai has no retroflex consonants. The equivalents of all the retroflex consonants are pronounced identically to their dental counterparts: thus ฏ is pronounced like ต, ฐ is pronounced like ถ, ฑ is pronounced like ท, ฒ is pronounced like ธ, and ณ is pronounced like น. The Sanskrit unaspirated unvoiced plosives are pronounced as unaspirated unvoiced, whereas Sanskrit aspirated voiced plosives are pronounced as aspirated unvoiced. Non-plosives (avargaḥ)Semivowels (กึ่งสระ kueng sara) and liquids come in Thai alphabetical order after ม, the last of the plosives. The term อวรรค awak means "without a break"; that is, without a plosive.

SibilantsInserted sounds (เสียดแทรก siat saek) follow the semi-vowel ว in alphabetical order.

Like Sanskrit, Thai has no voiced sibilant (so no 'z' or 'zh'). In modern Thai, the distinction between the three high-class consonants has been lost and all three are pronounced 'sà'; however, foreign words with a sh-sound may still be transcribed as if the Sanskrit values still hold (e.g., ang-grit อังกฤษ for English instead of อังกฤส).

Voiced h

ห, a high-class consonant, comes next in alphabetical order, but its low-class equivalent, ฮ, follows similar-appearing อ as the last letter of the Thai alphabet. Like modern Hindi, the voicing has disappeared, and the letter is now pronounced like English 'h'. Like Sanskrit, this letter may only be used to start a syllable, but may not end it. (A popular beer is romanized as Singha, but in Thai is สิงห์, with a karan on the ห; correct pronunciation is "sing", but foreigners to Thailand typically say "sing-ha".) Retroflex lla

This represents the retroflex liquid of Pali and Vedic Sanskrit, which does not exist in Classical Sanskrit. Vowels

All consonants have an inherent 'a' sound, and therefore there is no need to use the ะ symbol when writing Sanskrit. The Thai vowels อื, ใอ, and so forth, are not used in Sanskrit. The zero consonant, อ, is unique to the Indic alphabets descended from Khmer. When it occurs in Sanskrit, it is always the zero consonant and never the vowel o [ɔː]. Its use in Sanskrit is therefore to write vowels that cannot be otherwise written alone: e.g., อา or อี. When อ is written on its own, then it is a carrier for the implied vowel, a [a] (equivalent to อะ in Thai). The vowel sign อำ occurs in Sanskrit, but only as the combination of the pure vowels sara a อา with nikkhahit อํ. Other non-Thai symbolsThere are a number of additional symbols only used to write Sanskrit or Pali, and not used in writing Thai. Nikkhahit (anusvāra)

In Sanskrit, the anusvāra indicates a certain kind of nasal sound. In Thai this is written as an open circle above the consonant, known as nikkhahit (นิคหิต), from Pali niggahīta. Nasalisation does not occur in Thai, therefore, a nasal stop is always substituted: e.g. ตํ taṃ, is pronounced as ตัง tang by Thai Sanskritists. If nikkhahit occurs before a consonant, then Thai uses a nasal stop of the same class: e.g. สํสฺกฤตา [saṃskṛta] is read as สันสกฤตา san-sa-krit-ta (The ส following the nikkhahit is a dental-class consonant, therefore the dental-class nasal stop น is used). For this reason, it has been suggested that in Thai, nikkhahit should be listed as a consonant.[8] Also, traditional Pali grammars describe nikkhahit as a consonant. Nikkhahit นิคหิต occurs as part of the Thai vowels sara am อำ and sara ue อึ. Phinthu (virāma)อฺ Because the Thai script is an abugida, a symbol (equivalent to virāma in devanagari) needs to be added to indicate that the implied vowel is not to be pronounced. This is the phinthu, which is a solid dot (also called 'Bindu' in Sanskrit) below the consonant. Yamakkanอ๎ Yamakkan (ยามักการ) is an obsolete symbol used to mark the beginning of consonant clusters: e.g. พ๎ราห๎มณ phramana [brāhmaṇa]. Without the yamakkan, this word would be pronounced pharahamana [barāhamaṇa] instead. This is a feature unique to the Thai script (other Indic scripts use a combination of ligatures, conjuncts or virāma to convey the same information). The symbol is obsolete because pinthu may be used to achieve the same effect: พฺราหฺมณ. VisargaThe means of recording visarga (final voiceless 'h') in Thai has reportedly been lost, although the character ◌ะ which is used to transcribe a short /a/ or to add a glottal stop after a vowel is the closest equivalent and can be seen used as a visarga in some Thai-script Sanskrit text. SukhothaiThe Thai script is derived from the Sukhothai script. Sukhothai consonant inventory

Historical Sukhothai pronuncation

UnicodeThai script was added to the Unicode Standard in October 1991 with the release of version 1.0. The Unicode block for Thai is U+0E00–U+0E7F. It is a verbatim copy of the older TIS-620 character set which encodes the vowels เ, แ, โ, ใ and ไ before the consonants they follow, and thus Thai, Lao, Tai Viet and New Tai Lue are the only Brahmic scripts in Unicode that use visual order instead of logical order.

Keyboard layoutsThai characters can be typed using the Kedmanee layout and the Pattachote layout. See also

References

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Thai text.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||