|

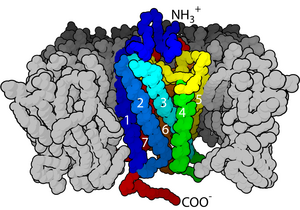

Cell surface receptor Cell surface receptors (membrane receptors, transmembrane receptors) are receptors that are embedded in the plasma membrane of cells.[1] They act in cell signaling by receiving (binding to) extracellular molecules. They are specialized integral membrane proteins that allow communication between the cell and the extracellular space. The extracellular molecules may be hormones, neurotransmitters, cytokines, growth factors, cell adhesion molecules, or nutrients; they react with the receptor to induce changes in the metabolism and activity of a cell. In the process of signal transduction, ligand binding affects a cascading chemical change through the cell membrane. Structure and mechanismMany membrane receptors are transmembrane proteins. There are various kinds, including glycoproteins and lipoproteins.[2] Hundreds of different receptors are known and many more have yet to be studied.[3][4] Transmembrane receptors are typically classified based on their tertiary (three-dimensional) structure. If the three-dimensional structure is unknown, they can be classified based on membrane topology. In the simplest receptors, polypeptide chains cross the lipid bilayer once, while others, such as the G-protein coupled receptors, cross as many as seven times. Each cell membrane can have several kinds of membrane receptors, with varying surface distributions. A single receptor may also be differently distributed at different membrane positions, depending on the sort of membrane and cellular function. Receptors are often clustered on the membrane surface, rather than evenly distributed.[5][6] MechanismTwo models have been proposed to explain transmembrane receptors' mechanism of action.

Domains P = plasma membrane I = intracellular space Transmembrane receptors in plasma membrane can usually be divided into three parts. Extracellular domainsThe extracellular domain is just externally from the cell or organelle. If the polypeptide chain crosses the bilayer several times, the external domain comprises loops entwined through the membrane. By definition, a receptor's main function is to recognize and respond to a type of ligand. For example, a neurotransmitter, hormone, or atomic ions may each bind to the extracellular domain as a ligand coupled to receptor. Klotho is an enzyme which effects a receptor to recognize the ligand (FGF23). Transmembrane domainsTwo most abundant classes of transmembrane receptors are GPCR and single-pass transmembrane proteins.[8][9] In some receptors, such as the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor, the transmembrane domain forms a protein pore through the membrane, or around the ion channel. Upon activation of an extracellular domain by binding of the appropriate ligand, the pore becomes accessible to ions, which then diffuse. In other receptors, the transmembrane domains undergo a conformational change upon binding, which affects intracellular conditions. In some receptors, such as members of the 7TM superfamily, the transmembrane domain includes a ligand binding pocket. Intracellular domainsThe intracellular (or cytoplasmic) domain of the receptor interacts with the interior of the cell or organelle, relaying the signal. There are two fundamental paths for this interaction:

Signal transduction Signal transduction processes through membrane receptors involve the external reactions, in which the ligand binds to a membrane receptor, and the internal reactions, in which intracellular response is triggered.[10][11] Signal transduction through membrane receptors requires four parts:

Membrane receptors are mainly divided by structure and function into 3 classes: The ion channel linked receptor; The enzyme-linked receptor; and The G protein-coupled receptor.

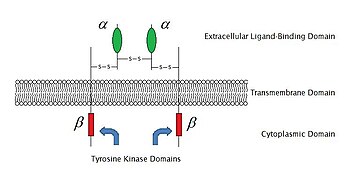

Ion channel-linked receptorDuring the signal transduction event in a neuron, the neurotransmitter binds to the receptor and alters the conformation of the protein. This opens the ion channel, allowing extracellular ions into the cell. Ion permeability of the plasma membrane is altered, and this transforms the extracellular chemical signal into an intracellular electric signal which alters the cell excitability.[12] The acetylcholine receptor is a receptor linked to a cation channel. The protein consists of four subunits: alpha (α), beta (β), gamma (γ), and delta (δ) subunits. There are two α subunits, with one acetylcholine binding site each. This receptor can exist in three conformations. The closed and unoccupied state is the native protein conformation. As two molecules of acetylcholine both bind to the binding sites on α subunits, the conformation of the receptor is altered and the gate is opened, allowing for the entry of many ions and small molecules. However, this open and occupied state only lasts for a minor duration and then the gate is closed, becoming the closed and occupied state. The two molecules of acetylcholine will soon dissociate from the receptor, returning it to the native closed and unoccupied state.[13][14] Enzyme-linked receptors As of 2009, there are 6 known types of enzyme-linked receptors: Receptor tyrosine kinases; Tyrosine kinase associated receptors; Receptor-like tyrosine phosphatases; Receptor serine/threonine kinases; Receptor guanylyl cyclases and histidine kinase associated receptors. Receptor tyrosine kinases have the largest population and widest application. The majority of these molecules are receptors for growth factors such as epidermal growth factor (EGF), platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), fibroblast growth factor (FGF), hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), nerve growth factor (NGF) and hormones such as insulin. Most of these receptors will dimerize after binding with their ligands, in order to activate further signal transductions. For example, after the epidermal growth factor (EGF) receptor binds with its ligand EGF, the two receptors dimerize and then undergo phosphorylation of the tyrosine residues in the enzyme portion of each receptor molecule. This will activate the tyrosine kinase and catalyze further intracellular reactions. G protein-coupled receptorsG protein-coupled receptors comprise a large protein family of transmembrane receptors. They are found only in eukaryotes.[15] The ligands which bind and activate these receptors include: photosensitive compounds, odors, pheromones, hormones, and neurotransmitters. These vary in size from small molecules to peptides and large proteins. G protein-coupled receptors are involved in many diseases, and thus are the targets of many modern medicinal drugs.[16] There are two principal signal transduction pathways involving the G-protein coupled receptors: the cAMP signaling pathway and the phosphatidylinositol signaling pathway.[17] Both are mediated via G protein activation. The G-protein is a trimeric protein, with three subunits designated as α, β, and γ. In response to receptor activation, the α subunit releases bound guanosine diphosphate (GDP), which is displaced by guanosine triphosphate (GTP), thus activating the α subunit, which then dissociates from the β and γ subunits. The activated α subunit can further affect intracellular signaling proteins or target functional proteins directly. Membrane receptor-related diseaseIf the membrane receptors are denatured or deficient, the signal transduction can be hindered and cause diseases. Some diseases are caused by disorders of membrane receptor function. This is due to deficiency or degradation of the receptor via changes in the genes that encode and regulate the receptor protein. The membrane receptor TM4SF5 influences the migration of hepatic cells and hepatoma.[18] Also, the cortical NMDA receptor influences membrane fluidity, and is altered in Alzheimer's disease.[19] When the cell is infected by a non-enveloped virus, the virus first binds to specific membrane receptors and then passes itself or a subviral component to the cytoplasmic side of the cellular membrane. In the case of poliovirus, it is known in vitro that interactions with receptors cause conformational rearrangements which release a virion protein called VP4.The N terminus of VP4 is myristylated and thus hydrophobic【myristic acid=CH3(CH2)12COOH】. It is proposed that the conformational changes induced by receptor binding result in the attachment of myristic acid on VP4 and the formation of a channel for RNA. Structure-based drug design Through methods such as X-ray crystallography and NMR spectroscopy, the information about 3D structures of target molecules has increased dramatically, and so has structural information about the ligands. This drives rapid development of structure-based drug design. Some of these new drugs target membrane receptors. Current approaches to structure-based drug design can be divided into two categories. The first category is about determining ligands for a given receptor. This is usually accomplished through database queries, biophysical simulations, and the construction of chemical libraries. In each case, a large number of potential ligand molecules are screened to find those fitting the binding pocket of the receptor. This approach is usually referred to as ligand-based drug design. The key advantage of searching a database is that it saves time and power to obtain new effective compounds. Another approach of structure-based drug design is about combinatorially mapping ligands, which is referred to as receptor-based drug design. In this case, ligand molecules are engineered within the constraints of a binding pocket by assembling small pieces in a stepwise manner. These pieces can be either atoms or molecules. The key advantage of such a method is that novel structures can be discovered.[20][21][22] Other examples

See alsoReferences

External links

|