|

Bulgarian phonology

This article discusses the phonological system of the Bulgarian language. The phonemic inventory of Contemporary Standard Bulgarian (CSB) has been a contested and controversial matter for decades, with two major currents, or schools of thought, forming at national and international level:[1][2][3][4][5] One school of thought assumes palatalization as a phonemic distinction in Contemporary Standard Bulgarian and consequently states that it has 17 palatalized phonemes, rounding its phonemic inventory to 45 phonemes.[6][7][8] This view, originally suggested in a sketch made by Russian linguist Nikolai Trubetzkoy in his 1939 book Principles of Phonology, was subsequently elaborated by Bulgarian linguists Stoyko Stoykov and Lyubomir Andreychin. It is the traditional and prevalent view in Bulgaria and is endorsed by the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences;[3] some international linguists also favour it.[9] The other view considers that there are only 28 phonemes in Contemporary Standard Bulgarian: 21 consonants, 1 semivowel and 6 vowels and that only one of them, the semivowel /j/, is palatal. This view is held by a minority of Bulgarian linguists and a substantial number of international ones.[10][11][12][13][3][9][14][15] Vowels

^1 /ɤ/ is actually a mid-back and somewhat centralized vowel, usually pronounced midway between [ɤ̞] and [ə]. Thus, it is sometimes transcribed as ⟨ə⟩,[16] or even ⟨ɜ⟩,[17] but its usual notation is ⟨ɤ⟩.

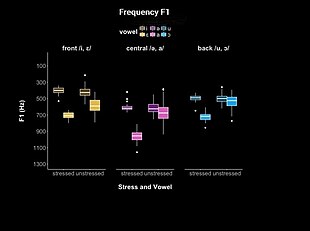

According to their place of articulation, Bulgarian vowels can be grouped in three pairs—front vowels: ⟨е⟩ (/ɛ/) and ⟨и⟩ (/i/); central vowels: ⟨а⟩ (/a/) and ⟨ъ⟩ (/ɤ/); and back vowels: ⟨о⟩ (/ɔ/) and ⟨у⟩ (/u/). Here /ɛ/, /a/ and /ɔ/ are "low", and /i/, /ɤ/ and /u/ are "high". The dominant theory of Bulgarian vowel reduction posits that Bulgarian vowels have a phonemic value only in stressed position, while when unstressed, they neutralize in an intermediate centralized position, where lower vowels are raised and higher vowels are lowered.[18][14] This concerns only the central vowels /a/ and /ɤ/, which neutralize into [ɐ], and the back vowels /ɔ/ and /u/, which neutralize into [o]. The merger of /ɛ/ and /i/ is not allowed in formal speech and is regarded as a provincial (East Bulgarian) dialectal feature; instead, unstressed /ɛ/ is both raised and centralized, approaching the schwa ([ə]).[19] The Bulgarian /ɤ/ vowel does not exist as a phoneme in other Slavic languages, though a similar reduced vowel transcribed as [ə] does occur. The theory further posits that such neutralization may nevertheless not always happen: vowels tend to be distinguished in emphatic or deliberately distinct pronunciation, while reduction is strongest in colloquial speech. Nevertheless, the hypothesis that high and low vowels neutralize into a common centralized vowel has never been properly studied or proven in a practical setting. Several recent studies by both Bulgarian and foreign researchers, involving volunteers speaking Contemporary Standard Bulgarian, have established—on the contrary—that while unstressed low vowels /ɛ/, /a/ and /ɔ/ are indeed raised as expected, unstressed high /ɤ/ and /u/ are also raised somewhat, rather than lowered, while /i/ remains in the same position.[20][21][22] All three studies indicate that a clear distinction is kept between unstressed /ɛ/ and both stressed and unstressed /i/. The situation with unstressed /a/ and /ɔ/ is more complex, but all studies indicate that they both approach unstressed /ɤ/ and /u/ very closely and overlap with them to a great extent, but their average realisations remain slightly more open. One of the studies finds that unstressed /a/ to be practically undistinguishable from stressed /ɤ/,[23] while another finds a lack of statistically significant difference between /ɔ/ and /u/,[22] and a third one finds coalescence only in formants for one of the pairs and only in tongue position for the other. While the difference between all stressed vowels and between unstressed /i/ and /ɛ/ can be heard in almost all cases, the unstressed back and central vowels are perceptually neutralised in minimal pairs, with only 62% identifying unstressed /u/, 59% unstressed /a/ and /ɔ/ and a mere 57% unstressed /ɤ/.[22] SemivowelsThe Bulgarian language officially has only one semivowel: /j/. It is traditionally regarded as a semivowel, but in recent years, it has largely been treated as a "glide" or approximant, thus making it part of the consonant system. Orthographically, it is represented by the Cyrillic letter ⟨й⟩ (⟨и⟩ with a breve) as in най- [naj] (prefix 'most') and (тролей [troˈlɛj] ('trolleybus'), except when it precedes /a/ or /u/ (and their reduced counterparts [ɐ] and [o]), in which case both phonemes are represented by a single letter, ⟨я⟩ or ⟨ю⟩, respectively: e.g., ютия [juˈtijɐ] ('flat iron'), but Йордан [jorˈdan] ('Jordan'). As a result of lenition of velarized /l/ ([ɫ]), ongoing since the 1970s, [w] appears to be an emerging allophone of velarized [ɫ] among younger speakers, especially in preconsonantal position: вълк [vɤwk] ('wolf') instead of [vɤɫk]. While certain Western Bulgarian dialects (in particular, those around Pernik), have had a long-standing tradition of pronouncing [ɫ] as [w], the use of the glide in the literary language was first noted by a radio operator in 1974.[24] A Ukrainian researcher found in 2012 that Bulgarians split into three age-specific groups in terms of [ɫ] pronunciation: 1) people in their 40s or older who have standard pronunciation; 2) people in their 30s, who can articulate [ɫ] but unconsciously say [w]; and 3) younger people who are unable to differentiate between the two sounds and generally say [w].[25] A study of 30 graduate students was therefore conducted in 2014 to quantify the trend. The study testified to an extremely wide proliferation of the phenomenon, with 9 out of 30 participants unable to produce [ɫ] in any given word, and only 2 participants able to produce [ɫ] correctly, but in no more than half the words in the study.[26] Remarkably, not a single participant was able to enunciate [ɫ] between a bilabial consonant and a rounded vowel, e.g., in аплодирани [ɐpwoˈdirɐni] ('applauded'), or between a rounded vowel and a velar consonant, e.g. in толкова [ˈtɔwkovɐ] ('so').[27] Another discovery of the study was that in particular positions, certain participants enunciated neither [ɫ] nor [w], but the high back unrounded vowel [ɯ] (or its corresponding glide [ɰ]). The glide [w] can also be found in English loan words such as уиски [ˈwiski] ('whiskey') or Уикипедия [ˈwikiˈpɛdiɐ] ('Wikipedia'). The semivowel /j/ forms a number of diphthongs, which are summarized below:[28][29]

ConsonantsTwo schools of thought on Bulgarian consonantismThe main point of contention between the two schools of thought on Bulgarian consonantism has been whether palatalized consonants should be defined as separate phonemes or simply as allophones of their respective hard counterparts. Until the 1940s, Bulgarian linguists classified the Bulgarian consonants without including any palatal or palatalized consonants other than /j/ and, sometimes, the postalveolars ([ʃ], [tʃ], [ʒ], [dʒ]). The palatalized consonant sounds, when mentioned, were described merely as positional variants (what would today be called allophones) of hard consonants. Accordingly, the Bulgarian language was considered to have only 28 consonants.[30] A phonological analysis aligned with this view, positing 28 phonemes and viewing the palatalized consonants as allophones, has maintained some currency outside of Bulgaria and has also been (re-)adopted by some Bulgarian linguists since as early as the 1970s and 1980s[9] and even more so after the end of the Communist period.[31][13][14] It has proposed alternative notation of palatalized consonants in the form of C-j-V (consonant-glide-vowel) clusters and has made a tentative hypothesis about the decomposition of Bulgarian palatals into consonants + glide using the following arguments:[4][32][2]

The second school of thought came to being rather unexpectedly in the late 1940s, as a refinement of Trubetzkoy's rough draft a decade before. It posits that apart from ⟨й⟩ (/j/), there are 17 separate palatal phonemes that are in minimal pairs with their hard counterparts, including дз' (/d͡zʲ/) and х' (/ç/), which are not found in any native Bulgarian words and were excluded from Trubetzkoy's draft.[40] Thus, only 5 consonants are not in minimal pairs, ⟨ч⟩ (/t͡ʃ/), ⟨дж⟩ (/d͡ʒ/), ⟨ш⟩ (/ʃ/) and ⟨ж⟩ (/ʒ/), which are only hard, and the glide ⟨й⟩ (/j/), which is only soft. They argue that Bulgarian phonemic inventory consists of a total of 45 phonemes, whereof 6 vowels, 1 semivowel and 38 consonants, and present the following arguments:[41]

Historical development of Bulgarian consonantismProto-Slavic underwent three separate rounds of palatalization and one of iotation, but the resulting palatal consonants eventually hardened in Western and South Slavic. By the Old Bulgarian period, there were only four consonants left forming contrastive pairs: р (/r/) and р' (/rʲ/), н (/n/) and н' (/ɲ/), л (/l/) and л' (/ʎ/), с (/s/) and с' (/sʲ/). Three consonants were only hard: к (/k/), г (/ɡ/) and х (/x/), four were only soft: /ʒ/, /t͡ʃ/, /ʃ/ and ꙃ' (/d͡zʲ/), while the remaining eight consonants were generally hard, but could be semi-palatalized: б (/b/), в (/β/), д (/d/), ꙁ (/z/), м (/m/), п (/p/), т (/t/) and ф (/f/).[43] Historical phonetician Anna-Maria Totomanova has expressed a slightly divergent opinion: the four hard/palatal contrastive pairs were again /r/ and /rʲ/, /n/ and /ɲ/, /l/ and /ʎ/, /s/ and /sʲ/, 11 consonants, /p/, /b/, /m/, (/f/, /β/), /d/, /t/, /z/, /k/, /ɡ/ and /x/, were only hard, and six consonants, /ʃ/, /ʒ/, /t͡ʃ/, /t͡sʲ/, /d͡zʲ/ and iota (/j/), along with the typically Bulgarian consonant combinations ⟨щ⟩ [ʃt] and ⟨жд⟩ [ʒd], were only soft.[44] Finally, Huntley mentions 9 palatal consonants: /ʃ/, /ʒ/, /t͡ʃ/, /t͡sʲ/, /d͡zʲ/ and /j/, which were only soft, and /ɲ/, /ʎ/ and /rʲ/, which could also be hard.[45] Both Haralampiev and Totomanova have noted a marked trend towards consonant hardening.[43] Eventually, /ʃ/, /ʒ/ and /t͡ʃ/ hardened permanently, /d͡z/ disappeared from the phonemic inventory, and ⟨дж⟩ (/d͡ʒ/) was borrowed from Ottoman Turkish as only hard. But before that, two phenomena led to the palatalization of more consonants: a second iotation and the dissolution of the yat vowel. As a result of the contraction and closure of the syllable in the Middle Bulgarian period, unstressed /i/ in many cases turned into the semivowel /j/ or attached to a consonant, palatalising it. Thus, Old Bulgarian свиниꙗ [sviˈnija] ('swine') contracted into свиня [sviˈɲa] and братиꙗ [ˈbratija] ('brothers') into братя [ˈbratʲɐ].[46] In many dialects, the resulting palatalised т' (/tʲ/) and д' (/dʲ/) turned into palatalised к' (/c/) and г' (/ɟ/).[47] These were subsequently eliminated from CSB as dialecticisms, e.g., цвет'e [ˈt͡svɛtʲɛ] ('flower')→ цвек'е [ˈt͡svɛkʲɛ] → Ø. The form accepted in the literary language was instead the unpalatalised цвете [ˈt͡svɛtɛ] based on the Old Bulgarian form. The dissolution of the yat happened somewhat later, towards the end of the Middle Bulgarian period and had different effects on the various dialects. In most of the East, yat in a stressed syllable softened the preceding consonant and turned into /a/. In the West, however, it led to /ɛ/ in both stressed and unstressed syllables producing no palatalisation anywhere.[48] This was one of the main factors that led to the markedly different patterns of palatalisation in Western and Eastern Bulgarian dialects, i.e., strong palatalisation of only 5 consonants in the West vs. moderate palatalisation of almost all consonants in the East. Development of phonological theory before 1945The first Bulgarian grammar to mention phonetics is Ivan Bogorov's First Bulgarian Grammar, where he identified 22 consonants, however, including among them ⟨щ⟩ (ʃt), ⟨ъ⟩ and ⟨ь⟩ (no phonemic status at word end).[49] In 1868, Ivan Momchilov identified only 21 consonants.[50] Momchilov observed that Bulgarian consonants could sound hard or soft, entirely depending on the vowel accompanying them.[51] Phonetics only started developing seriously after World War I, and towards the 1930s, all major Bulgarian linguists had reached consensus that Bulgarian phonemic inventory consisted of 28 phonemes. Out of the six major Bulgarian grammars published in the Interwar period, five explicitly mention the existence of 22 consonants (including the semivowel /j/) and 6 vowels: Petar Kalkandzhiev,[52] Aleksandar Teodorov-Balan, who suggested 20 certain consonants + 2 conditional ones (for the non-native and infrequent ⟨дж⟩ (/d͡ʒ/) and ⟨дз⟩ (/d͡z/)),[12] Dimitar Popov, who posited that the only soft or palatal consonant in Bulgarian was ⟨й⟩ (/j/),[53] as well as Lyubomir Andreychin, who mentioned the distinctive articulation of palatalised consonants, but did not ascribe them phonemic status.[54] All phoneticians referenced palatalisation extensively, but without ascribing phonemic value to the resulting sounds. Moreover, according to Stefan Mladenov,[55]

This was a result of the attempts to unify the extremely divergent patterns of Eastern and Western palatalization into a common standard in the 1800s and early 1900s, which eventually led to its general elimination from the standard language. Examples include the complete elimination of end-word palatals in a number of words ending in ⟨р'⟩ (/rʲ/), ⟨н'⟩ (/ɲ/), ⟨л'⟩ (/ʎ/) and ⟨т'⟩ (/tʲ/), e.g., writing and saying кон [kɔn] ('horse') instead of The opinions of Bulgarian linguistics were also shared by a number of foreign Slavicists. French linguist Léon Beaulieux has stated that Bulgarian is characterised by its tendency to eliminate all palatal consonants.[57] Czech linguist Horalek claimed as early as the 1940s that palatalisation in standard Bulgarian was on its way to disappear through decomposition and the development of a specific /j/ glide and that words such as бял (white) and дядо (grandfather) were pronounced [bjaɫ] and [ˈdjado] (i.e., CjV) or even [biaɫ] and [ˈdiado] just as often as they were pronounced [bʲaɫ] and [ˈdʲado].[58] Bulgarian consonantism according to IPA (22-consonant model)A graphic representation of the Bulgarian consonant systems according to the International Phonetic Association (22 consonants) follows below:[14]

^2 [ɱ] only appears as an allophone of /m/ and /n/ before /f/ and /v/. For example, инфлация [iɱˈflat͡sijɐ] ('inflation'). In other words, /m/ and /n/ always neutralize into [ɱ] before /f/ and /v/.[59] ^3 /n/ is usually elided before fricatives but nasalizes and usually lengthens the preceding vowel (V + [n] + CFricative → VNasalised + Ø + CFricative). Examples: бранш [brãːʃ] ('line of business'), конски [ˈkɔ̃ski] ('of a horse').[60] ^4 [ŋ] only exists as an allophone of /n/ before /k/, /ɡ/ and /x/. Examples: тънко [ˈtɤŋko] ('thin' neut.), танго [tɐŋˈɡɔ] ('tango').[61] ^5 /d͡z/ is only used in a handful of native words, and its use in dialects or foreign proper names is not wider. Thus, some phonologists include the phoneme into the phonemic inventory on a provisional basis only or not at all.[12][62] ^6 [ɣ] only exists as an allophone of /x/, and its distribution is rather restricted. It appears only before voiced obstruents other than /v/ (i.e., only across word boundaries. Example: видях го [viˈdʲaɣɡo] ('I saw him'). ^8 [w] is not a native phoneme. It appears in borrowings from English, where it is often vocalised as /u/ (or as the fricative /v/ in a handful of very old borrowings adopted through German or Russian), e.g. уиски [ˈwiski] ('whiskey'), Уилям [ˈwiʎɐm] ('William'). Always marked with the Cyrillic letter ⟨у⟩ /u/ in Bulgarian orthography.[64] Allophone of /ɫ/ among younger speakers,[65] apparently causing an ongoing sound change, cf. Semivowels above. ^9 /l/ as a phoneme in Bulgarian has three allophones in complementary distribution; "clear" [l], occurring before front vowels, "dark" or velarized [ɫ] occurring before central and back vowels, in between vowels and before consonants, and palatalized [ʎ], occurring before /j/ and a central or back vowel. As palatalized consonants have very limited distribution in Standard Bulgarian and are only possible in syllable-initial position before central/back vowels, IPA's consonant table above treats them as palatalized allophones of their respective "hard" counterparts + [j] rather than as palatal phonemes and suggests that they can unambiguously be interpreted as CjV (consonant-glide-vowel) clusters.[11]<[10] Thus, for example, някой [nʲakoj] ('somebody') can easily be reanalysed as [njakoj]. According to Ternes and Vladimirova-Buhtz:[66]

Among modern Bulgarian phoneticians, strong opinions about the existence of 22 consonants only are held by, e.g., Blagoy Shklifov, Mitko Sabev, Andrey Danchev and especially by Dimitrina Ignatova-Tzoneva, who has consistently argued that palatal consonants, though present in a number of dialects and in earlier stages of the development of the Bulgarian language, have largely been eliminated from Contemporary Standard Bulgarian.[67][68] All of them have advocated for a CjV reanalysis of palatalization. A large number of other Bulgarian linguists have come out in support of this more minimalistic view of Bulgarian consonantism, e.g., Kiril Mirchev,[69] Petar Pashov,[70] Bozhil Nikolov,[71] Todor Boyadzhiev,[72] Борис Симеонов, who has argued that there was no logic that could explain why a consonant affected by yat mutation (e.g., /b/ in бял-бели [bʲaɫ]-[ˈbɛli]) would be palatal in some of its forms and hard in others, and so on.[73] A number of foreign linguists have rejected the 39-consonant model based on an analysis of the distribution and degree of "softening" of Bulgarian "palatals" and the number of speakers pronouncing ⟨bj⟩, ⟨dj⟩ or ⟨fj⟩ instead of ⟨bʲ⟩, ⟨dʲ⟩ or ⟨fʲ⟩. These have included Austrian researcher Merlingen (1957),[74] Americans Carleton Hodge (1957)[75] and Joseph van Campen and Jacob Ornstein (1959),[76] Romanian linguist Alexandru Rosetti, who qualified the degree of palatalization of Bulgarian consonants as "a softening" (1967),[77] Swiss Max Mangold (1988),[78] Korean Slavist Gwon-Jin Choi, who has argued about the decomposition of Bulgarian palatalism (into C + j) (1994),[4][36] as well as phoneticians Ternes and Vladimirova-Buhtz, who have most recently suggested C-j-V notation of palatals, as their limited distribution proved they were allophones rather than phonemes (1999).[14] A comparison of the distribution of palatalized consonants in Bulgarian and other Slavic languages and of the number of palatals in each major Slavic languages is of key importance for understanding the issue:

All other palatalized consonants in Bulgarian have the same distribution:

It is argued that it is highly unlikely for modern Bulgarian to have developed 18 palatalized consonants (incl. /j/) from the 9 or 10 that existed in Old Bulgarian (/ʃ/, /ʒ/, /t͡ʃ/, /t͡sʲ/, /d͡zʲ/, /j/, /ɲ/, /ʎ/, /rʲ/ and /sʲ/), considering that four of those had already hardened or disappeared (/ʃ/, /ʒ/, /t͡ʃ/, /d͡zʲ/).[84] Townsend and Janda have argued that such a development is at odds with the general development in all South Slavic languages, which had suppressed the development of palatals very early.[85] If Bulgarian indeed had 18 palatal phonemes, it would be as palatal a language as Russian and Belarussian, which runs counter to auditory experience. Bulgarian consonantism according to BAS (39-consonant model)A graphic representation of the Bulgarian consonant system according to the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences and based on Trubetzkoy's ideas follows below (39 consonants):[41]

^2 [ɱ] only appears as an allophone of /m/ and /n/ before /f/ and /v/. For example, инфлация [iɱˈflat͡sijɐ] ('inflation'). In other words, /m/ and /n/ always neutralize into [ɱ] before /f/ and /v/.[59] ^3 /n/ is usually elided before fricatives but nasalizes and usually lengthens the preceding vowel (V + [n] + CFricative → VNasalized + Ø + CFricative). Examples: бранш [brãːʃ] ('line of business'), конски [ˈkɔ̃ski] ('of a horse').[60] ^4 [ŋ] only exists as an allophone of /n/ before /k/, /ɡ/ and /x/. Examples: тънко [ˈtɤŋko] ('thin' neut.), танго [tɐŋˈɡɔ] ('tango').[61] ^5 /d͡z/ is only used in a handful of native words, and its use in dialects or foreign proper names is not wider. Thus, some phonologists include the phoneme into the phonemic inventory on a provisional basis only or not at all.[12][86] ^6 [ɣ] only exists as an allophone of /x/, and its distribution is rather restricted. It appears only before a voiced obstruent other than /v/ (i.e., only across word boundaries. Example: видях го [viˈdʲaɣɡo] ('I saw him').[87] ^8 [w] is not a native phoneme. It appears in borrowings from English, where it is often vocalised as /u/ (or as the fricative /v/ in a handful of very old borrowings adopted through German or Russian), e.g. уиски [ˈwiski] ('whiskey'), Уилям [ˈwiʎɐm] ('William'). Always marked with the Cyrillic letter ⟨у⟩ /u/ in Bulgarian orthography.[64] Allophone of /ɫ/ among younger speakers,[65] apparently causing an ongoing sound change, cf. Semivowels above. ^9 /l/ as a phoneme in Bulgarian has three versions in complementary distribution: clear [ɫ] occurring before central and back vowels, in between vowels and before consonants; [l], occurring before front vowels and considered allophonic to [ɫ]; and palatalized [ʎ], occurring before a central or back vowel.[88] ^10 According to Klagstad Jr. (1958:46–48), /t tʲ d dʲ s sʲ z zʲ n/ are dental. He also analyzes /ɲ/ as palatalized dental nasal, and provides no information about the place of articulation of /t͡s t͡sʲ r rʲ l ɫ/. ^11 [d͡zʲ] and [xʲ] do not exist in any native words, which has caused even phonologists who accept Trubetzkoy/BAN's model to remove them from the phonemic inventory.[89]

The 39-consonant model is inextricably linked to Russian linguist Nikolai Trubetzkoy. A refugee from the Bolshevik Revolution, he settled in Sofia in 1920, where he was granted tenure at Sofia University.[90] Eventually, he moved to Vienna and became one of the founders of the immensely influential Prague Linguistic Circle.[91] In his magnum opus, Principles of Phonology, published posthumously in 1939, he referenced extensively Eastern Bulgarian, even offering a model phonemic inventory it.[92] There he argued in favor of the existence of the distinctive feature of palatalization in Bulgarian, establishing 14 contrastive pairs of hard and palatalized consonants. The consonant inventory suggested by Trubetzkoy consisted of 36 consonants, including й (/j/), but not дз (/d͡z/), дз' (/d͡zʲ/) and х' (/ç/). By the turn of the 1940s, Bulgarian linguist Stoyko Stoykov had adopted Trubetzkoy's consonant model, adding 15 palatalized consonants to his analysis of the Bulgarian phonemic inventory.[93] The other major postwar Bulgarian linguist, Lyubomir Andreychin, then quickly suggested another two, /d͡zʲ/ and /ç/, arguing that even though they only existed in foreign proper names like Хюстън /xʲustɤn/ ('Houston') and Ядзя [jad͡zʲa] ('Jadzia') and had no contrastive function, they could have one, if need be. Stoykov eventually accepted the inclusion of these phonemes, too, and after the most distinguished Bulgarian phonetician of the Communist period, Димитър Тилков, also agreed to the inclusion ("as they were entailed by the system"), the 39-consonant system was set in stone.[94] Tilkov designated /d͡zʲ/ and /ç/ as "potential phonemes", adding ф' (/fʲ/) to them in 1982, as it existed in only a handful of words, all of them borrowings (e.g., фюрер [ˈfʲurɛr] ('Führer')).[95] The "potential phoneme"approach has not enjoyed much support abroad, where most authors generally omit not only /d͡zʲ/ and /ç/, but also /d͡z/.[96][97][98] While the consonant model was lauded in the Soviet Union by linguists such as, e.g., Yuriy Maslov, acceptance in the West, except for Klagstad, has been lukewarm.[citation needed] Most of those who have opted to go with it rather than with the alternative model routinely call into question parts of it or make caveats. The most prolific Bulgarian phonologist and grammarian in the English-speaking world, Ernest Scatton, notes (1993):[99]

In the compilation Common and Comparative Slavic (1996), American Slavist Charles E. Townsend states:[15]

According to Voegelin (1965):[100]

PalatalizationPalatalization refers to a type of consonant articulation, where a secondary palatal movement similar to that for /i/ is superimposed on the primary movement associated with the consonant's plain counterpart.[101] During the palatalization of most hard consonants (bilabial, labiodental and denti-alveolar consonants), the middle part of the tongue is raised toward the hard palate and the alveolar ridge, which leads to the formation of a second articulatory centre whereby the specific palatal "clang" of the soft consonants is achieved. The articulation of palatalised alveolars /l/, /n/ and /r/ normally does not follow that rule. The palatal clang is instead achieved by moving the place of articulation further back towards the palate so that /ʎ/, /ɲ/ and /rʲ/ actually become alveopalatal (postalveolar) consonants. In turn, the articulation of soft /ɡ/ and /k/ (transcribed as /ɡʲ/ and /kʲ/ or /ɟ/ and /c/) moves from the velum towards the palate, and they are therefore considered palatal consonants. However, the only articulatory study of palatalized consonants in Bulgarian, conducted by Stoyko Stoykov via X-ray tracings of vocal tract configurations of hard/palatalised consonant pairs, indicates that the secondary palatal movement is missing (or severely weakened) during the articulation of a number of palatalized consonants.[102] Only the articulation of bilabial and labiodental consonants (/pʲ/, /bʲ/, /mʲ/, /fʲ/, /vʲ/) is accompanied by a noticeable raising of the body of the tongue towards the palate, but only to a moderate extent.[103] The articulation of soft /k/, /ɡ/ and /x/ (/c/, /ɟ/ and /ç/) also shows distinctive palatalization, as the place of articulation moves onto the palate.[104] However, in denti-alveolars (/tʲ/, /dʲ/, /tsʲ/, /dzʲ/, /sʲ/, /zʲ/), the place of articulation neither shifts towards the palate, nor is the tongue raised. Instead, they are articulated with the blade of the tongue (laminally) rather than the tip (apically), which results in greater surface contact of the tongue front and a modification of the primary articulatory gesture.[105][106] Stoykov defines them as "weakly palatalized", while Scatton notes that the position of the mid-tongue in palatalized stops is not much higher than that in their plain counterparts.[107][108] A comparison with the articulation of the same consonants in a language where palatal consonants indisputably exist, such as Russian, reveals drastically different articulation, with Bulgarian being completely non-conformant with the definition of palatalization.[109] A comparison of the articulation of bilabials and labiodentals (/pʲ/, /bʲ/, /mʲ/, /fʲ/, /vʲ/) in Bulgarian also reveals much less pronounced secondary palatal gesture than in Russian. The articulation of /ʎ/, /ɲ/ and /rʲ/ is very similar to that of the denti-alveolars, but with a slight shift of the place of articulation towards the palate and some raising of the mid-tongue towards the palate.[110] According to Stoykov, /ʎ/ and /ɲ/ are harder than their counterparts in the other Slavic languages, while /rʲ/ is just as palatal.[110] Based on Stoykov's study, several foreign and Bulgarian phonologists have noted that distinctive palatalization in Bulgarian can be only claimed in the cases of /c/, /ɟ/, /ʎ/ and /ɲ/,[111][112][100] or /c/, /ɟ/, /ç/ and /ʎ/.[32] Moreover, a study of the perception of hard and palatlized consonants conducted by Tilkov in 1983 has indicated that with the exception of palatalized velars (/c/, /ɟ/, /ç/), Bulgarian listeners needed to hear the transition to the vowel to correctly identify a consonant as soft.[113] All this has raised the question whether Bulgarian palatals have indeed lost their secondary articulatory gesture and have decomposed into CjV sequences, as claimed by Danchev, Ignatova-Tzoneva, Choi, etc. A 2012 perception study of palatalized consonants in Bulgarian compared with a language where palatalization is indisputed (Russian) and a language where such consonants are undoubtedly articulated as CjV clusters (English) concluded that unlike English listeners, Russian and Bulgarian listeners could identify a palatal(ized) consonant without waiting for the transition to the following vowel.[114] The study also found similarities in the phonetic shape of palatal(ized) consonants in Bulgarian and Russian and marked differences between those in the two languages and English, disproving the hypothesis for the decomposition of palatalization put forward by Horalek, Ignatova-Tzoneva, Choi, etc.[114] Nevertheless, based on the phonological distribution of Bulgarian palatals, which was similar to that in English and completely different from that in Russian, the author argued in favour of CjV notation.[114] Palatalization of *tj/*gt/*kt and *dj in BulgarianWhile the results of the three Slavic palatalizations are generally the same across all or most Slavic languages, the palatalization of *tj (and the related *gti and *kti) and *dj in Late Common Slavic led to vastly divergent result in each individual Slavic language.

Bulgarian *tj/*kti/*gti and *dj reflexes ⟨щ⟩ ([ʃt]) and ⟨жд⟩ ([ʒd]), which are exactly the same as in Old Church Slavonic, and the near-open articulation [æ] of the Yat vowel (ě), which is still widely preserved in a number of Bulgarian dialects in the Rhodopes, Pirin Macedonia (Razlog dialect) and northeastern Bulgaria (Shumen dialect), etc., are the strongest evidence that Old Church Slavonic was codified on the basis of a Bulgarian dialect and that Bulgarian is its closest direct descendant.[116] Though the ⟨ʃt⟩/⟨ʒd⟩ speaking area currently covers only the territory of the Republic of Bulgaria and the eastern half of the wider region of geographical Macedonia, toponomy containing ⟨ʃt⟩ and ⟨ʒd⟩ that goes back to the Early Middle Ages is widely preserved across Northern and Central Greece, Southern Albania, the Republic of Macedonia, Kosovo and the Torlak-speaking regions in Serbia.[116][117] For example, in the Struga municipality, the names of 13 out of 43 villages contain either ⟨ʃt⟩ (Kališta, Korošišta, Labuništa, Moroišta, Piskupština, Radolišta, Tašmaruništa, Velešta and Vraništa) or ⟨ʒd⟩ (Delogoždi, Mislodežda, Radožda and Zbaždi).[116] The same applies to Kosovo, where Russian Slavist Afanasiy Selishchev found а number of place names around the city of Prizren featuring the Bulgarian clusters ⟨ʃt⟩/⟨ʒd⟩ in a Serbian official document from the 1300s (Nebrěgošta, Dobroušta, Sěnožeštani, Graždenikī, Obražda, Ljubižda, etc.).[118] At present, a total of 8 villages out of 76 villages in the Prizren municipality still feature the Bulgarian consonant clusters ⟨ʃt⟩/⟨ʒd⟩, even though the region has not been ruled by Bulgaria in eight centuries: Lubizhdë, Lubizhdë e Hasit, Poslishtë, Skorobishtë, Grazhdanik, Nebregoshtë, Dobrushtë, Kushtendil. There are also numerous toponyms with the two clusters in the districts of Vranje, Pirot, Knjaževac, etc. in Serbia proper.[119] The development of ⟨ʃt⟩ > /c/ and ⟨ʒd⟩ > /ɟ/ in certain dialects in the geographic region of Macedonia is a late and partial phenomenon dating back to the Late Middle Ages, probably caused by the influence of Serbian /t͡ɕ/ and /d͡ʑ/, and possibly aided by the Late Middle Bulgarian's trend to palatalise /t/ and /d/ and then transform them into soft k and g > /c/ and /ɟ/.[120][121][122] PhonationPhonation is a primary distinctive feature for obstruents in Bulgarian, dividing them into voiced and voiceless consonants. Obstruents form 8 minimal pairs: /p/↔/b/, /f/↔/v/, /t/↔/d/, /t͡s/↔/d͡z/, /s/↔/z/, /ʃ/↔/ʒ/, /t͡ʃ/↔/d͡ʒ/, /k/↔/ɡ/.[123] The only obstruent without a counterpart is the voiceless fricative /x/, whose voiced counterpart /ɣ/ does not exist as a separate phoneme in Bulgarian. The sonorants /m/, /n/, /l/ and /r/ and the approximant /j/ are always voiced. If the existence of separate palatalised consonant phonemes (39-consonant model) is accepted, 6 more contrastive obstruent pairs are added: /pʲ/↔/bʲ/, /fʲ/↔/vʲ/, /tʲ/↔/dʲ/, /sʲ/↔/zʲ/, /tsʲ/↔/dzʲ/, /ɟ/↔/c/, for a total of 14. Voicing, devoicing, assimilation, sandhi, ellisionLike all other Slavic languages apart from Serbo-Croatian and Ukrainian, Bulgarian features word-final devoicing of obstruents, unless the following word begins with a voiced consonant.[124] Thus, град is pronounced [ˈgrat] ('city'), жив is pronounced [ˈʒif] ('alive'). While obstruents devoice before enclitics (град ли [ˈgratli] ('а city?')), they do not devoice at the end of prepositions followed by a voiced consonant (под липите [podliˈpitɛ] ('under the lindens')). CSB also features regressive assimilation in consonant clusters. Thus, voiced obstruents devoice if they are followed by a voiceless obstruent (e.g., изток is pronounced [ˈistok]) ('East')), and voiceless obstruents voice if they are followed by a voiced obstruent (e.g., сграда is pronounced [ˈzgradɐ] ('building')).[125] Assimilation also occurs across word boundaries (in the form of sandhi), for example, от гората is pronounced [odgoˈratɐ] ('from the forest'), while над полето becomes [natpoˈlɛto] ('above the field').[126] The consonants /t/ and /d/ in consonant clusters such as стн [stn] and здн [zdn] are usually not pronounced, unless the articulation is very careful, i.e., вестник tends to pronounced as [ˈvɛsnik] ('newspaper'), while бездна tends to pronounced as [ˈbeznɐ]) ('abyss').[127] Distribution of voiced and voiceless consonants in Bulgarian

^a The very limited distribution of /d͡z/ is yet another indicator that it is unable to function as a fully-fledged phoneme in CSB and should instead be regarded as an allophone of /z/, as suggested by Scatton.[89]

Consonant classification based on place and manner of articulationPlace of articulationThe consonants:

The palatalized allophones of

Manner of articulation

Word stressStress is not usually marked in written text. In cases where the stress must be indicated, a grave accent is placed on the vowel of the stressed syllable.13 Bulgarian word stress is dynamic. Stressed syllables are louder and longer than unstressed ones. As in Russian and other East Slavic languages, as well as English, Bulgarian stress is also lexical rather than fixed as in French, Latin or the West Slavic languages. It may fall on any syllable of a polysyllabic word, and its position may vary depending on the inflection and derivation, for example:

Bulgarian stress is also distinctive: the following examples are only differentiated by stress (see the different vowels):

Stress usually isn't signified in written text, even in the above examples, if the context makes the meaning clear. However, the grave accent may be written if confusion is likely.15 The stress is often written in order to signify a dialectal deviation from the standard pronunciation:

^13 For practical purposes, the grave accent can be combined with letters by pasting the symbol "

̀" directly after the designated letter. An alternative is to use the keyboard shortcut Alt + 0300 (if working under a Windows operating system), or to add the decimal HTML code "̀" after the targeted stressed vowel if editing HTML source code. See "Accute accent" diacritic character in Unicode, Unicode character "Cyrillic small letter i with grave" and Unicode character "Cyrillic capital letter i with grave" for the exact Unicode characters that utilize the grave accent. Retrieved 2010-06-21.^14 Note that the last example is only spelled the same in the masculine. In the feminine, neuter and the plural, it is spelled differently—e.g. vzrìvna ('explosive' fem.), vzrivèna ('exploded' fem.), etc. ^15 However, the grave accent is obligatorily used to disambiguate between the two non-stressed words—* и ('and'), ѝ ('to her'). Since many computer programs do not allow for accents on Cyrillic letters, "й" is sometimes seen instead of "ѝ". ^16 Note that in this case the accent would be written in order to differentiate it from the present tense иска да дойде /ˈiskɐ dɐ dojdɛ/ ('he wants to come'). References

Bibliography

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Portal di Ensiklopedia Dunia