|

Würzburg witch trials

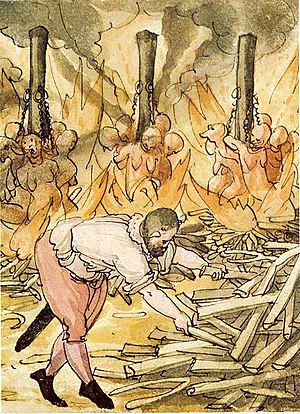

The Würzburg witch trials of 1625–1631, which took place in the self-governing Catholic Prince-Bishopric of Würzburg in the Holy Roman Empire in present-day Germany, formed one of the biggest mass trials and mass executions ever seen in Europe, and one of the largest witch trials in history. The trials resulted in the execution of hundreds of people of all ages, sexes and classes, all of whom were burned at the stake, sometimes after having been beheaded, sometimes alive. One hundred fifty-seven women, children and men in the city of Würzburg are confirmed to have been executed; 219 are estimated to have been executed in the city proper, and an estimated 900 were executed or died in custody in the Prince-Bishopric. The witch trials took place during the ongoing religious Thirty Years War between Protestants and Catholics, in an area on the religious border between Catholic and Protestant territories, and were conducted by a Catholic Prince Bishop intent on introducing the Counter-Reformation in his territory. The Würzburg witch trials were among the largest Witch trials in the Early Modern period: the series was one of the four largest in Germany along with the Trier witch trials, the Fulda witch trials, and the Bamberg witch trials.[1] HistoryContextThe first persecutions in Würzburg started with the consent of Julius Echter von Mespelbrunn, Prince bishop of Würzburg, and reached its climax during the reign of his nephew and successor Philipp Adolf von Ehrenberg. They started in the territory around the city in 1626 and evaporated in 1630. As so often with the mass trials of sorcery, the victims soon counted people from all society, including nobles, councilmen and mayors. This was during a witch hysteria that caused a series of witch trials in South Germany, such as in Bamberg, Eichstätt, Mainz and Ellwangen. In the 1620s, with the destruction of Protestantism in Bohemia and the Electorate of the Palatinate, the Catholic reconquest of Germany was resumed. In 1629, with the Edict of Restitution, its basis seemed complete. Those same years saw, in central Europe at least, the worst of all witch-persecutions, the climax of the European craze. Many of the witch-trials of the 1620s multiplied with the Catholic reconquest. In some areas the lord or bishop was the instigator, in others the Jesuits. Sometimes local witch-committees were set up to further the work. Among prince-bishops, Philipp Adolf von Ehrenberg of Würzburg was particularly active: in his reign of eight years (1623–31) he burnt 900 persons, including his own nephew, nineteen Catholic priests, and children of seven who were said to have had intercourse with demons. The years 1627–29 were dreadful years in Baden, recently reconquered for Catholicism by Tilly: there were 70 victims in Ortenau, 79 in Offenburg. In Eichstätt, a Bavarian prince-bishopric, a judge claimed the death of 274 witches in 1629. At Reichertshofen, in the district of Neuburg an der Donau, 50 were executed between November 1628 and August 1630. In the three prince-archbishoprics of the Rhineland the fires were also relit. At Coblenz, the seat of the Prince-Archbishop of Trier, 24 witches were burnt in 1629; at Sélestat at least 30—the beginning of a five-year persecution. In Mainz, too, the burnings were renewed. At Cologne the City Fathers had always been merciful, much to the annoyance of the prince-archbishop, but in 1627 he was able to put pressure on the city and it gave in. Naturally enough, the persecution raged most violently in Bonn, his own capital. There, the chancellor and his wife, and the archbishop's secretary's wife, were executed; children of three and four years were accused of having devils for their paramours, and students and small boys of noble birth were sent to the bonfire. The craze of the 1620s was not confined to Germany: it raged also across the Rhine in Alsace, Lorraine and Franche-Comté. In the lands ruled by the abbey of Luxueil, in Franche-Comté, the years 1628–30 have been described as an "épidémie démoniaque." "Le mal va croissant chaque jour", declared the magistrates of Dôle, "et cette malheureuse engeance va pullulant de toutes parts." The witches, they said, "in the hour of death accuse an infinity of others in fifteen or sixteen other villages."[citation needed] Local background and outbreakThe witchcraft persecutions in Würzburg was initiated by the Reform Catholic and Counter-Reformation Catholic Prince Bishop Julius Echter von Mespelbrunn, Prince Bishop of Würzburg in 1609–1622. In 1612 he incorporated the Protestant city of Freudenburg in the Catholic Bishopric, which resulted in a witch trial with fifty executions.[2] This was followed by a witch trial in Würzburg itself, where 300 people were executed between July 1616 and July 1617,[2] before the persecutions suddenly stopped at the outbreak of the Thirty Years War in 1618.[3] The exact cause of the witch trials of 1625-1631 is not entirely clear due to the incomplete documentation. A first witch trial took place in 1625, though it was an isolated case. In 1626, the vine grape harvest was destroyed by frost.[3] Upon rumours that the frost had been caused by sorcery, some suspects were arrested and confessed under torture that they had caused the frost by use of magic.[3] Legal process The Würzburg witch trials of 1625-1631 was initiated by the Reform Catholic and Counter-Reformation Catholic Prince Bishop Philipp Adolf von Ehrenberg, Prince Bishop of Würzburg in 1623–1631, who was the nephew and successor of Julius Echter von Mespelbrunn. The territory was close to the Catholic-Protestant religious border, and the goal of the new Prince Bishop was to create a "godly state" in accordance with the ideals of the Counter-Reformation, and to make the population obedient, devout and conformally Catholic,[3] and when witchcraft was rumoured to exist in the city, he ordered an investigation. A special Witch Commission was organized with the task to handle all cases of witchcraft.[2] The Witch Commission used torture without any of the restrictions regulated by the Constitutio Criminalis Carolina, in order to force the accused to first confess to their own guilt and then to name accomplices and other they had seen performing magic or attending the Witches' Sabbath. Those who had been named as accomplices were arrested in turn and tortured to name new accomplices, which caused the witch trial to expand rapidly in number of arrests and executions, especially since the Witch Commission did not discriminate in which names to accept but arrested men and women of all ages and classes indiscriminately.[3] Cases and accused Typical for both the Würzburg witch trial as well as the parallel witch trial in Bamberg, members of the elite were arrested after having been named by working-class people under torture, which was a phenomenon which would normally not have happened in contemporary society, if the process had been about a different crime. Würzburg and Bamberg, however, differed somewhat in that in Würzburg, many members of the clerical elite were arrested, and many children were among the accused.[3] The first arrests in the city were of the traditionally suspected poor working-class women, but as the trials expanded in size, more and more men and children from all classes were among the accused, and in the later years of the trials, men were sometimes in the majority of the executed.[2] Forty-three priests were executed, as well as Ernst von Ehrenberg, nephew of the Prince Bishop himself.[3][4] At least 49 children under the age of twelve are confirmed to have been executed,[3] many of them from the orphanage and school Julius-Spital.[5] A contemporary letter from 1629 describes how people of all ages and classes were arrested every day. A third of the population was suspected of having attended the Witches' Sabbath and being noted in the black book of Satan that the authorities were searching for.[3] People from all walks of life were arrested and charged, regardless of age, profession, or sex, for reasons ranging from murder and satanism to humming a song including the name of the Devil, or simply for being vagrants and unable to give a satisfactory explanation of why they were passing through town: 32 appear to have been vagrant. The exact number of executions is not known, since documentation is only partially preserved. A list describes 157 executions from 1627 until February 1629 in the city itself, but Hauber who preserved the list in Acta et Scripta Magica, noted that the list was far from complete and that there were a great many other burnings, too many to specify. February 1629 was furthermore in the middle of the witch trials, which continued for two more years until 1631. The executions within the city itself have been estimated at 219, with another 900 in the areas under the authority of the Prince Bishop outside the city. It has been referred to as the greatest witch trial in the history of Franconia, just ahead of the contemporaneous Bamberg witch trials of 1626–1630.[citation needed] The endThe ongoing mass process in Würzburg attracted considerable attention. That the Witch Commission accepted the names of supposed accomplices given by people undergoing torture indiscriminately, regardless of societal standing, had the result that many of those arrested had influential relatives and connections among the upper class. Such persons had resources to escape the territory and to issue complaints against the Prince Bishop and his witch trials to his superiors, all the way to the Pope himself, as well as to the Holy Roman Emperor. In 1630, after just such a complaint to the Imperial Chamber Court in Speyer, a public condemnation against the persecutions was issued by the Emperor.[2] On 16 July 1631, the Prince Bishop Philipp Adolf von Ehrenberg died. That same year, the city was occupied by the Swedish Army under King Gustavus Adolphus, and the witch trials were finally brought to an end. Legacy and aftermath In contemporary Germany, the gigantic, parallel mass witch trials of Würzburg and Bamberg were seen as role models by other states and cities interested in investigating witchcraft, notably Wertheim and Mergentheim.[5] The Würzburg witch trials influenced the start of the Mergentheim witch trials in 1628,[5] and unrestricted witchcraft persecutions came to be known as "Würzburgisch work".[2] AccountsWhile the parallel Bamberg witch trials are famous for the contemporary letter of the prisoner Johannes Junius to his daughter, the Würzburg witch trials are famous for the contemporary letter written by a councillor of the Prince Bishop to a friend, describing the ongoing witch hunt. In August, 1629, the Chancellor of the Prince-Bishop of Würzburg thus wrote (in German) to a friend:

Friedrich SpeeA Jesuit, Friedrich Spee, was more radically converted by his experience as a confessor of witches in the great persecution at Würzburg. That experience, which turned his hair prematurely white, convinced him that all confessions were worthless, being based solely on torture, and that not a single person whom he had led to the stake had been guilty. Since he could not utter his thoughts otherwise — for, as he wrote, he dreaded the fate of Tanner [clarification needed] — he wrote a book which he intended to circulate in manuscript, anonymously. However, a friend secretly conveyed it to the Protestant city of Hameln, where it was printed in 1631 under the title Cautio Criminalis.[3] FictionA German novel, Der Aufruhr um den Junker Ernst (The uproar over the junker Ernst), by Jakob Wassermann (1873-1934), published in 1926 by S. Fischer Verlag in Berlin, took place during the trials with the main character being one of the most known victims; Ernst von Ehrenberg, nephew of the Prince Bishop. The list of executions There is a famous list of the executions in the Würzburg witch trials, published in 1745 in the Eberhard David Hauber: Bibliotheca sive acta et scripta magica. Gründliche Nachrichten und Urtheile von solchen Büchern und Handlungen, welche die Macht des Teufels in leiblichen Dingen betreffen, 36 Stücke in 3 Bänden. Lemgo 1738-1745, Bibl. mag. 36. Stück, 1745, S. 807. The list is, however, incomplete, being based on a document which explicitly states that it has cited only a selection of the executions, and that there were numerous other burnings beside those enumerated. Furthermore, the list includes only executions carried out before the date 16 February 1629, at which time the trials were still ongoing, continuing for more than another two years. Most of those listed as executed are not identified by name, but instead in terms such as Gobel's child, aged nineteen, "The prettiest girl in town", "A wandering boy, twelve years of age" or "Four strange men and women, found sleeping in the market-place". The accusation of "strange" often simply meant that they were not residents of Würzburg or were believed to be Protestants. The list gives the following cases:[4] In the First Burning, Four people.

In the Second Burning, Four people.

In the Third Burning, Five people.

In the Fourth Burning, Five people.

In the Fifth Burning, Eight people.

In the Sixth Burning, Six people

In the Seventh Burning, Seven people.

In the Eighth Burning, Seven people.

In the Ninth Burning, Five people.

In the Tenth Burning, Three people.

In the Eleventh Burning, Four people.

In the Twelfth Burning, Two people.

In the Thirteenth Burning, Four people.

In the Fourteenth Burning, Two people.

In the Fifteenth Burning, Two people.

In the Sixteenth Burning, Six people. A noble page of Ratzenstein, was executed in the chancellor's yard at six o'clock in the morning, and left upon his bier all day, and then next day burnt with the following:

In the Seventeenth Burning, Four people.

In the Eighteenth Burning, Six people.

In the Nineteenth Burning, Six people.

In the Twentieth Burning Six people.

In the Twenty-first Burning, Six people.

In the Twenty- second Burning, Six people.

In the Twenty-third Burning, Nine people.

In the Twenty-fourth Burning, Seven people.

In the Twenty-fifth Burning, Six people.

In the Twenty-sixth Burning, Seven people.

In the Twenty-seventh Burning, Seven people.

In the Twenty-eighth Burning, after Candlemas, 1629, Six people.

In the Twenty-ninth Burning, Seven people.

References

External links

Sources

|

Portal di Ensiklopedia Dunia