|

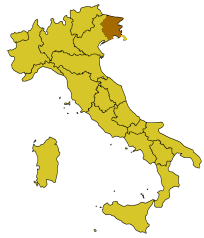

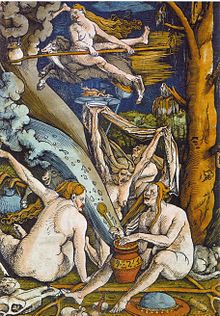

BenandantiThe benandanti ("Good Walkers") were members of an agrarian visionary tradition in the Friuli district of Northeastern Italy during the 16th and 17th centuries. The benandanti claimed to travel out of their bodies while asleep to struggle against malevolent witches (malandanti) in order to ensure good crops for the season to come. Between 1575 and 1675, in the midst of the Early Modern witch trials, a number of benandanti were accused of being heretics or witches under the Roman Inquisition. According to Early Modern records, benandanti were believed to have been born with a caul on their head, which gave them the ability to take part in nocturnal visionary traditions that occurred on specific Thursdays during the year. During these visions, it was believed that their spirits rode upon various animals into the sky and off to places in the countryside. Here they would take part in various games and other activities with other benandanti, and battle malevolent witches who threatened both their crops and their communities using sticks of sorghum. When not taking part in these visionary journeys, benandanti were also believed to have magical powers that could be used for healing. In 1575, the benandanti first came to the attention of the Friulian Church authorities when a village priest, Don Bartolomeo Sgabarizza, began investigating the claims made by the benandante Paolo Gasparotto. Although Sgabarizza soon abandoned his investigations, in 1580 the case was reopened by the inquisitor Fra' Felice de Montefalco, who interrogated not only Gasparotto but also a variety of other local benandanti and spirit mediums, ultimately condemning some of them for the crime of heresy. Under pressure by the Inquisition, these nocturnal spirit travels (which often included sleep paralysis) were assimilated to the diabolised stereotype of the witches' Sabbath, leading to the extinction of the benandanti cult. The Inquisition's denunciation of the visionary tradition led to the term "benandante" becoming synonymous with the term "stregha" (meaning "witch") in Friulian folklore right through to the 20th century. The first historian to study the benandanti tradition was the Italian Carlo Ginzburg, who began an examination of the surviving trial records from the period in the early 1960s, culminating in the publication of his book The Night Battles: Witchcraft and Agrarian Cults in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries (1966, English translation 1983). In Ginzburg's interpretation of the evidence, the benandanti was a "fertility cult" whose members were "defenders of harvests and the fertility of fields". He furthermore argued that it was only one surviving part of a much wider European tradition of visionary experiences that had its origins in the pre-Christian period, identifying similarities with Livonian werewolf beliefs.[1] Various historians[who?] have alternately built on or challenged aspects of Ginzburg's interpretation. Members The benandanti – a term meaning "good walkers"[2] – were members of a folk tradition in the Friuli region. The benandanti, who included both males and females, were individuals who believed that they ensured the protection of their community and its crops. The benandanti reported leaving their bodies in the shape of mice, cats, rabbits, or butterflies. The men mostly reported flying into the clouds battling against witches to secure fertility for their community; the women more often reported attending great feasts. Across Europe, popular culture viewed magical abilities as either innate or learned; in Friulian folk custom, the benandanti were seen as having innate powers marked out at birth.[2] Specifically, it was a widely held belief that those who in later life became benandanti were born with a caul, or amniotic sac, wrapped around their heads.[3][4] In the folklore of Friuli at the time, cauls were imbued with magical properties, being associated with the ability to protect soldiers from harm, to cause an enemy to withdraw, and to help lawyers win their legal cases.[5] In subsequent centuries, a related folkloric tradition found across much of Italy held to the belief that witches had been born with a caul.[5] From surviving records, it is apparent that members of the benandanti first learned about its traditions during infancy, usually from their mothers.[6] For this reason, historian Norman Cohn asserted that the benandanti tradition highlights how "not only the waking thoughts but the trance experiences of individuals can be deeply conditioned by the generally accepted beliefs of the society in which they live".[7] Visionary journeysAlthough these were described by benandanti as spirit journeys, they nevertheless stressed the reality of such experiences, believing that they were real occurrences.[8] On Thursdays between the Ember days, periods of fasting for the Catholic Church, the benandanti claimed their spirits would leave their bodies at night in the form of small animals. The spirits of the men would go to the fields to fight evil witches (malandanti[9]). The benandanti men fought with fennel stalks, while the witches were armed with sorghum stalks (sorghum was used for witches' brooms, and the "brooms' sorghum" was one of the most current type of sorghum). If the men prevailed, the harvest would be plentiful.[10] The female benandanti performed other sacred tasks. When they left their bodies they traveled to a great feast, where they danced, ate and drank with a procession of spirits, animals and faeries, and learned who amongst the villagers would die in the next year. In one account, this feast was presided over by a woman, "the abbess", who sat in splendour on the edge of a well. Carlo Ginzburg has compared these spirit assemblies with others reported by similar groups elsewhere in Italy and Sicily, which were also presided over by a goddess-figure who taught magic and divination. The earliest accounts of the benandanti's journeys, dating from 1575, did not contain any of the elements then associated with the diabolic witches' sabbath; there was no worshipping of the Devil (a figure who was not even present), no renunciation of Christianity, no trampling of crucifixes and no defilement of sacraments.[11] Relationship with witchesGinzburg noted that whether the benandanti were themselves witches or not was an area of confusion in the earliest records. Whilst they combated the malevolent witches and helped heal those who were believed to have been harmed through witchcraft, they also joined the witches on their nocturnal journeys, and the miller Pietro Rotaro was recorded as referring to them as "benandanti witches"; for this reason the priest Don Bartolomeo Sgabarizza, who recorded Rotaro's testimony, believed that while the benandanti were witches, they were 'good' witches who tried to protect their communities from the bad witches who would harm children. Ginzburg remarked that it was this contradiction in the relationship between the benandanti and the malevolent witches that ultimately heavily influenced their persecution at the hands of the Inquisition.[11] Inquisition and persecution Sgabarizza's investigation: 1575In early 1575, Paolo Gasparotto, a male benandante who lived in the village of Iassico (modern spelling: Giassìcco), gave a charm to a miller from Brazzano named Pietro Rotaro, in the hope of healing his son, who had fallen sick from some unknown illness. This event came to the attention of the local priest, Don Bartolomeo Sgabarizza, who was intrigued by the use of such folk magic, and called Gasparotto to him to learn more. The benandante told the priest that the sick child had "been possessed by witches" but that he had been saved from certain death by the benandanti, or "vagabonds" as they were also known.[12] He went on to reveal more about his benandanti brethren, relating that "on Thursdays during the Ember Days of the year [they] were forced to go with these witches to many places, such as Cormons, in front of the church at Giassìcco, and even into the countryside around Verona," where they "fought, played, leaped about, and rode various animals", as well as taking part in an activity during which "the women beat the men who were with them with sorghum stalks, while the men had only bunches of fennel."[12]

Don Sgabarizza was concerned with such talk of witchcraft, and on 21 March 1575, he appeared as a witness before both the vicar general, Monsignor Jacopo Maracco, and the Inquisitor Fra Giulio d'Assis, a member of the Order of the Minor Conventuals, at the monastery of San Francesco of Cividale del Friuli, in the hope that they could offer him guidance in how to proceed in this situation. He brought Gasparotto with him, who readily furnished more information in front of the Inquisitor, relating that after taking part in their games, "the witches, warlocks and vagabonds" would pass in front of people's houses, looking for "clean, clear water" that they would then drink. According to Gasparotto, if the witches could not find any clean water to drink, they would "go into the cellars and overturn all the wine".[14] Sgabarizza did not initially believe Gasparotto's claim that these events had actually occurred. In response to the priest's disbelief, Gasparotto invited both him and the Inquisitor to join the benandanti on their next journey, although refused to provide the names of any other members of the "fraternity", stating that he would be "badly beaten by the witches" should he do so.[15] Not long after, on the Monday following Easter, Sgabarizza visited Giassìcco in order to say Mass to the assembled congregation, and following the ritual stayed among the locals for a feast held in his honour.[16] During and after the meal, Sgabarizza once more discussed the journeys of the benandanti with both Gasparotto and the miller Pietro Rotaro, and later learned of another self-professed benandante, the public crier Battista Moduco of Cividale, who offered more information on what occurred during their nocturnal visions. Ultimately, Sgabarizza and the inquisitor Giulio d'Assisi decided to abandon their investigations into the benandanti, something the later historian Carlo Ginzburg believed was probably because they came to believe that their stories of nocturnal flights and battling witches were "tall tales and nothing more".[16] Montefalco's investigation: 1580–1582Gasparotto and ModucoFive years after Sgabarizza's original investigation, on 27 June 1580, the inquisitor Fra Felice da Montefalco decided to revive the case of the benandanti. To do so he ordered Gasparotto to be brought in for questioning; under interrogation, Gasparotto repeatedly denied having ever been a benandante and asserted that involvement in such things were against God, contradicting the former claims that he had made to Sgabarizza several years before. The questioning over, Gasparotto was imprisoned.[13] That same day, the public crier of Cividale, Battista Moduco, who was also known locally to be a benandante, was rounded up and interrogated at Cividale, but unlike Gasparotto, he openly admitted to Montefalco that he was a benandante, and went on to describe his visionary journeys, in which he battled witches in order to protect the community's crops. Vehemently denouncing the actions of the witches, he claimed that the benandanti were fighting "in service of Christ", and ultimately Montefalco decided to let him go.[17]

On 28 June, Gasparotto was brought in for interrogation again. This time he admitted to being a benandante, claiming that he had been too scared to do so in the previous interrogation lest the witches beat him in punishment. Gasparotto went on to accuse two individuals, one from Gorizia and the other from Chiana, of being witches, and was subsequently released by Montefalco on the proviso that he return for further questioning at a later date.[19] This eventually came about on 26 September, taking place at the monastery of San Francesco in Udine. This time, Gasparotto added an extra element to his tale, claiming that an angel had summoned him to join the benandanti. For Montefalco, the introduction of this element led him to suspect that the actions of Gasparotto were themselves heretical and satanic, and his method of interrogation became openly suggestive, putting forward the idea that the angel was actually a demon in disguise.[20] As historian Carlo Ginzburg related, Montefalco had begun to warp Gasparotto's testimony of the benandanti journey to fit the established clerical image of the diabolical witches' sabbat, while under the stress of interrogation and imprisonment, Gasparotto himself was losing his self-assurance and beginning to question "the reality of his beliefs".[21] Several days later, Gasparotto openly told Montefalco that he believed that "the apparition of that angel was really the devil tempting me, since you have told me he can transform himself into an angel". When Moduco was also summoned to Montefalco, on 2 October 1580, he went on to announce the same thing, proclaiming that the Devil must have deceived him into going on the nocturnal journey which he believed was performed for good.[22] Having both confessed to Montefalco that their nocturnal journeying had been caused by the devil, both Gasparotto and Moduco were released, pending sentencing for their crime at a later date.[23] Due to a jurisdictional conflict between the Cividale commissioner and the patriarch's vicar, the pronouncement of Gasparotto and Moduco's punishment was postponed until 26 November 1581. Both denounced as heretics, they were spared from excommunication but condemned to six months' imprisonment, and furthermore ordered to offer prayers and penances to God on certain days of the year, including the Ember Days, in order that He might forgive their sins. However, their penalties were soon remitted, on the condition that they remain within the city of Cividale for a fortnight.[23] Anna la Rossa, Donna Aquilina and Caterina la GuerciaGasparotto and Moduco would not be the only victims of Montefalco's investigations, however, for during late 1581 he had heard of a widow living in Udine named Anna la Rossa (the Red one). While she did not claim to be a benandante, she did claim that she could see and communicate with the spirits of the dead, and so Montefalco had her brought in for questioning on 1 January 1582. Initially denying that she had such an ability to the inquisitor, she eventually relented and told him of how she believed that she could see the dead, and how she sold their messages to members of the local community willing to pay, using the money in order to alleviate the poverty of her family. Although Montefalco intended to interrogate her again at a later date, the trial ultimately remained permanently unfinished.[24] That year, Montefalco also took an interest in the claims regarding the wife of a tailor living in Udine who allegedly had the power to see the dead and to cure diseases with the use of spells and potions. Known among locals as Donna Aquilina, she was said to have become relatively rich through offering her services as a professional healer, but when she learned that she was under suspicion from the Holy Inquisition, she fled the city, and Montefalco did not initially set out to locate her. Later, on 26 August 1583, Montefalco traveled to Aquilina's home in order to interrogate her, but she fled and hid in a neighbouring house. She was finally brought in for interrogation on 27 October, in which she defended her practices, but claimed that she was neither a benandante nor a witch.[25] In 1582, Montefalco had also begun investigating a Cividale widow named Caterina la Guercia (the One-eyed one), whom he had accused of practicing "various maleficent arts". Under interrogation on 14 September, she admitted that she knew several charms which she used to cure children's sicknesses, but that she was not a benandante. She added however that her deceased husband, Andrea of Orsaria, near Premariacco, had been a benandante, and that he used to enter trances in which his spirit would leave his body and go with the "processions of the dead".[26] Subsequent depositions and denunciations: 1583–1629In 1583, an anonymous individual denounced a herdsman, Toffolo di Buri of Pieris, to the Holy Office at Udine. The village of Pieris was near Monfalcone, across the Isonzo river and therefore outside of Friuli; it was nevertheless within the diocese of Aquileia. The anonymous source claimed that Toffolo openly admitted to being a benandante, and that he went out at night on his visionary journeys to battle the witches. The source also asserted that Toffolo regularly attended confession, recognising that his activities as a benandante were contrary to the teachings of the Catholic Church, but that he was unable to stop the journeying.[27] Having heard this testimony, the members of the Holy Office of Udine met on 18 March to discuss the situation; they requested that the Mayor of Monfalcone, Antonia Zorzi, arrest Toffolo and send him to Udine. While Zorzi did orchestrate the arrest, he had no men spare to transfer the prisoner, and so let him go. In November 1586, the inquisitor of Aquileia decided to reinvestigate the matter, and travelled to Monfalcone, but discovered that Toffolo had moved away from the area over a year before.[27] On 1 October 1587, a priest known as Don Vincenzo Amorosi of Cesana denounced a midwife named Caterina Domenatta to the inquisitor of Aquileia and Concordia, Fra Giambattista da Perugia. Lambasting Domenatta as a "guilty sorceress", he claimed that she had encouraged mothers to put their newborn children on a spit in order to prevent them from becoming either benandanti or witches. Agreeing to investigate, the inquisitor travelled to Monfalcone in January 1588 to gain depositions against the midwife. When he came to interrogating Domenatta, she openly admitted to the practice, and was condemned to public penance and an abjuration.[28] In 1600, a woman named Maddalena Busetto of Valvasone made two depositions regarding the benandanti of Moruzzo village to Fra Francesco Cummo of Vicenza, the commissioner of the Inquisition in the dioceses of Aquileia and Concordia. Claiming that she wanted to unburden her conscience, Busetto informed the commissioner that she had visited the village, where she met a friend whose child was injured. Seeking out the perpetrator of the injury, she talked to the old woman she believed to be guilty, Pascutta Agrigolante, who claimed that she was a benandante and knew witches.[29] Busetto did not know what the benandanti were, so enquired further, to which Agrigolante obliged by providing her an account of the nocturnal journeys. Agrigolante also named several other benandanti who lived locally, including the village priest and a woman named Narda Peresut. Busetto proceeded to seek out Peresut, who admitted to being a benandante but who stated that she performed her healing magic in Gao to avoid prosecution from the Inquisition. Busetto would inform the commissioner that she did not believe any of these claims, but while he agreed to investigate further, there is no evidence that he ever did.[29] That same year, a self-professed benandante named Bastian Petricci of Percoto was also denounced to the Holy Office, although it is not recorded that they took any action on the issue.[30] In 1606, Giambattista Valento, an artisan from Palmanova, went to the superintendent general of the Patria del Friuli[31] Andrea Garzoni, and informed him of his belief that his wife had been bewitched. Garzoni was concerned, and sent the inquisitor general, Fra Gerolamo Asteo, to Palmanova to investigate. Asteo found that the villagers widely concurred that Valento's wife had been the victim of witchcraft, and a benandante was implicated, an 18-year-old shop assistant named Gasparo. Talking to Gasparo, Asteo heard the stories of the nocturnal journeys, but the young benandante was insistent that they served God rather than the devil. Gasparo proceeded to name some of the villagers as witches, but the inquisitor did not believe him, and brought the case to a close.[32] In 1609 this was followed by the denunciation of another benandante, a peasant named Bernardo of Santa Maria la Longa, to the religious authorities.[33] In 1614, a woman named Franceschina of Frattuzze arrived at the monastery of San Francesco in Portogruaro in order to denounce a folk magician named Marietta Trevisana of Giai as a witch. Although not described as a benandante, Trevisana's work in claiming to combat witchcraft might have indicated that she would have considered herself to be of the benandanti.[33] In 1618, a woman from Latisana, Maria Panzona, was arrested for theft. While imprisoned, it was revealed that she described herself as a benandante and worked as a professional healer and anti-witch. She proceeded to accuse a number of local women of being witches, but when questioned further in January 1619 admitted that she had paid homage to the devil, but only to gain powers which she used to help people.[34] She was subsequently moved to Venice, there to be tried for heresy in front of the Holy Office, and two women whom she accused of witchcraft were also summoned. Here, Panzona denied ever honouring the devil, insisting that she and other benandanti served Jesus Christ.[35] The members of the Holy Office did not believe that the stories she related ever took place, allowing the two accused witches to go free, and condemning Panzona to a three-year prison sentence for heresy.[35] In 1621, a wealthy man named Alessandro Marchetto of Udine submitted a memorandum to the Holy Office accusing both a fourteen-year-old boy and a local shepherd named Giovanni of being benandanti, each of whom he had previously tried to employ to cure his own cousin, whom it was believed had been bewitched by sorcery.[36] Ginzburg suggests that by the 1620s, the benandanti were becoming bolder in their public accusations against alleged witches.[37] In February 1622 the inquisitor of Aquileia, Fra Domenico Vico of Osimo was informed that a beggar and benandante named Lunardo Badou had been accusing various individuals of being witches in the area of Gagliano, Cividale del Friuli, and Rualis. Badou had become unpopular locally as a result, with the inquisitor not taking his claims seriously and proceeding to ignore the situation.[38] In 1623 and again in 1628–29 a series of depositions were made against Gerolamo Cut, a peasant and benandante from Percoto, who had been healing individuals who were believed to have been afflicted by witchcraft; he had proceeded to accuse various local individuals of being witches, but his accusations led nowhere.[39] In May 1629 Francesco Brandis, an official at Cividale, sent a letter to the inquisitor of Aquileia informing him that a twenty-year-old benandante had been arrested for theft and was thus due to be transferred to Venice.[40] LegacyFolk terminologyIn the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Italian folklorists – such as G. Marcotti, E. Fabris Bellavitis, V. Ostermann, A. Lazzarini and G. Vidossi – who were engaged in the study of Friulian oral traditions, noted that the term benandante had become synonymous with the term "witch", a result of the original Church persecutions of the benandanti.[41] Historical investigation and interpretationDuring the 1960s, the Italian historian Carlo Ginzburg was searching through the Archepiscopal Archives of Udine when he came across the 16th and 17th century trial records which documented the interrogation of several benandanti and other folk magicians.[42] Historian John Martin of Trinity University in San Antonio, Texas would later characterize this lucky find as the sort of "discovery most historians only dream of".[42] Since 1970, the trend for interpreting elements of Early Modern witchcraft belief as having ancient origins proved popular among scholars operating in continental Europe, but far less so than in the Anglophone world of Great Britain and the United States, where scholars were far more interested in understanding these witchcraft beliefs in their contemporary contexts, such as their connection to gender and class relations.[43] Various scholars were critical of Ginzburg's interpretation. In Europe's Inner Demons (1975), English historian Norman Cohn asserted that there was "nothing whatsoever" in the source material to justify the idea that the benandanti were the "survival of an age-old fertility cult".[44] The German anthropologist Hans Peter Duerr briefly discussed the benandanti in his book Dreamtime: Concerning the Boundary between Wilderness and Civilization (1978, English translation 1985). Like Ginzburg before him, he compared them to the Perchtenlaufen and the Livonian werewolf, arguing that they all represented a clash between the forces of order and chaos.[45] Gábor Klaniczay argued that the benandanti were part of a wider survival of pre-Christian rites, and points to the survival of broadly similar practices (differing in both names and minor details) in the Balkans, Hungary and Romania during the same period.[46] Popular culture

Connections and originsA pre-Christian shamanistic survival?In The Night Battles, Ginzburg argues that the benandanti tradition was connected to "a larger complex of traditions" that were spread "from Alsace to Hesse and from Bavaria to Switzerland", all of which revolved around "the myth of nocturnal gatherings" presided over by a goddess figure, varyingly known as Perchta, Holda, Abundia, Satia, Herodias, Venus or Diana. He also noted that "almost identical" beliefs could be found in Livonia (modern Latvia and Estonia), and that because of this geographic spread "it may not be too daring to suggest that in antiquity these beliefs may once have covered much of central Europe".[52] Romanian historian of religion Mircea Eliade agreed with Ginzburg's theory, describing the benandanti as "a popular and archaic secret cult of fertility".[53] Other historians were sceptical of Ginzburg's theories. In 1975, English historian Norman Cohn asserted that there was "nothing whatsoever" in the source material to justify the idea that the benandanti were the "survival of an age-old fertility cult".[44] Echoing these views in 1999 was English historian Ronald Hutton, who stated that Ginzburg's claim that the benandanti's visionary traditions were a survival from pre-Christian practices was an idea resting on "imperfect material and conceptual foundations".[54] Explaining his reasoning, Hutton remarked that "dreams do not self-evidently constitute rituals, and shared dream-imagery does not constitute a 'cult'," before noting that Ginzburg's "assumption" that "what was being dreamed about in the sixteenth century had in fact been acted out in religious ceremonies" dating to "pagan times" was entirely "an inference of his own". He thought that this approach was a "striking late application" of "the ritual theory of myth", a discredited anthropological idea associated particularly with Jane Ellen Harrison's 'Cambridge group' and Sir James Frazer.[55] Related traditionsThe themes associated with the benandanti (leaving the body in spirit, possibly in the form of an animal; fighting for the fertility of the land; banqueting with a queen or goddess; drinking from and soiling wine casks in cellars) are found repeatedly in other testimonies: from the armiers of the Pyrenees, from the followers of Signora Oriente in 14th century Milan and the followers of Richella and "the wise Sibillia" in 15th century Northern Italy, and much further afield, from Livonian werewolves, Dalmatian kresniki, Serbian zduhaćs, Hungarian táltos, Romanian căluşari and Ossetian burkudzauta.[46] Historian Carlo Ginzburg posits a relationship between the benandanti cult and the shamanism of the Baltic and Slavic cultures, a result of diffusion from a central Eurasian origin, possibly 6,000 years ago. This explains, in his opinion, the similarities between the Italian benandanti cult and a distant case in Livonia concerning a benevolent werewolf.[56] In 1692 in Jürgensburg, Livonia, an area near the Baltic Sea, an old man named Theiss was tried for being a werewolf. His defense was that his spirit (and that of others) transformed into werewolves in order to fight demons and prevent them from stealing grain from the village. Ginzburg has shown that his arguments, and his denial of belonging to a Satanic cult, corresponded to those used by the benandanti. On 10 October 1692, Theiss was sentenced to ten whip strikes on charges of superstition and idolatry.[57] ReferencesFootnotes

Bibliography

External links |