|

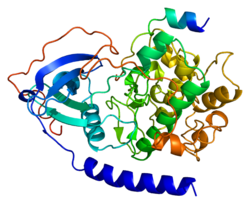

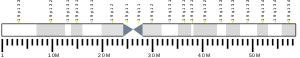

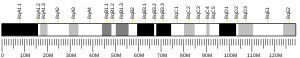

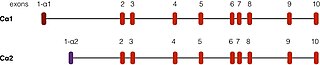

PRKACAThe catalytic subunit α of protein kinase A is a key regulatory enzyme that in humans is encoded by the PRKACA gene.[5] This enzyme is responsible for phosphorylating other proteins and substrates, changing their activity. Protein kinase A catalytic subunit (PKA Cα) is a member of the AGC kinase family (protein kinases A, G, and C), and contributes to the control of cellular processes that include glucose metabolism, cell division, and contextual memory.[6][7][8] PKA Cα is part of a larger protein complex that is responsible for controlling when and where proteins are phosphorylated. Defective regulation of PKA holoenzyme activity has been linked to the progression of cardiovascular disease, certain endocrine disorders and cancers. DiscoveryEdmond H. Fischer and Edwin G. Krebs at the University of Washington discovered PKA in the late 1950s while working through the mechanisms that govern glycogen phosphorylase. They realized that a key metabolic enzyme called phosphorylase kinase was activated by another kinase that was dependent on the second messenger cyclic AMP (cAMP).[9] They named this new enzyme the cAMP-dependent protein kinase, and proceeded to purify and characterize this new enzyme. Fischer and Krebs won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1992 for this discovery and their continued work on kinases, and their counterparts the protein phosphatases. Today, this cAMP-dependent protein kinase is more simply noted as PKA. Another key event in the history of PKA occurred when Susan Taylor and Janusz Sowadski at the University of California San Diego solved the three dimensional structure of the catalytic subunit of the enzyme.[10] It was also realized that inside cells, PKA catalytic subunits are found in complex with regulatory subunits and inhibitor proteins that block the activity of the enzyme. An additional facet of PKA action that was pioneered by John Scott at the University of Washington and Kjetil Tasken at the University of Oslo is that the enzyme is tethered within the cell through its association with a family of A-kinase-anchoring proteins (AKAPs). This led to the hypothesis that the subcellular localization of anchored PKA controls what proteins are regulated by the kinase.[11] Catalytic subunits PRKACA is found on chromosome 19 in humans.[5] There are two well-described transcripts of this gene, arising from alternative splicing events. The most common form, called Cα1, is expressed throughout human tissue. Another transcript, called Cα2, is found primarily in sperm cells and differs from Cα1 only in the first 15 amino acids.[12] In addition, there are two other isoforms of the catalytic subunit of PKA called Cβ and Cγ arising from different genes but have similar functions as Cα.[13][14] Cβ is found abundantly in the brain and in lower levels in other tissues, while Cγ is most likely expressed in the testis. Signaling Inactive PKA holoenzyme exists as a tetramer composed of two regulatory (R) subunits and two catalytic (C) subunits.[15] Biochemical studies demonstrated that there are two types of R subunits. The type I R subunits of which there are two isoforms (RIα, and RIβ) bind the catalytic subunits to create the type I PKA holoenzyme. Likewise type II R subunits, of which there are two isoforms (RIIα, and RIIβ), create the type II PKA holoenzyme. In the presence of cAMP, each R subunit binds 2 cAMP molecules and causes a conformational change in the R subunits that releases the C subunits to phosphorylate downstream substrates.[16] The different R subunits differ in their sensitivity to cAMP, expression levels and subcellular locations. A-kinase-anchoring proteins (AKAPs) bind a surface formed between both R subunits and target the kinase to different locations in the cell. This optimizes where and when cellular communication occurs within the cell.[11] Clinical significanceProtein kinase A has been implicated in a number of diseases, including cardiovascular disease, tumors of the adrenal cortex, and cancer. It has been speculated that abnormally high levels of PKA phosphorylation contributes to heart disease. This affects excitation-contraction coupling, which is a rhythmic process that controls the contraction of cardiac muscle through the synchronized actions of calcium and cAMP responsive enzymes.[17] There is also evidence to support that the mis-localization of PKA signaling contributes to cardiac arrhythmias, specifically Long QT syndrome. This results in irregular heartbeats that can cause sudden death. Mutations in the PRKACA gene that promote abnormal enzyme activity have been linked to disease of the adrenal gland. Several mutations in PRKACA have been found in patients with Cushing's syndrome that result in an increase in the ability of PKA to broadly phosphorylate other proteins. One mutation in the PRKACA gene that causes an amino acid substitution of leucine to arginine in position 206, was found in over 60% of patients with adrenocortical tumors.[18] Other mutations and genetic alterations in the PRKACA gene have been identified in adrenocortical adenomas that also disrupt PKA signaling, leading to aberrant PKA phosphorylation. The Cα gene has also been incriminated in a variety of cancers, including colon, renal, rectal, prostate, lung, breast, adrenal carcinomas and lymphomas. There is recent and growing interest in fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma. The molecular basis for this rare form of liver cancer that afflicts young adults is a genetic deletion on chromosome 19. The loss of DNA has been found in a very high percent of patients.[19] The consequence of this deletion is the abnormal fusion of two genes- DNAJB1, which is the gene that codes for the heat shock protein 40 (Hsp40), and PRKACA. Further analyses of fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma tissues show an increase in protein levels of this DNAJ-PKAc fusion protein. This is consistent with the hypothesis that increased kinase in liver tissues can initiate or perpetuate this rare form of liver cancer. Given the wealth of information on the three dimensional structures of DNAJ and PKA Cα there is some hope that new drugs can be developed to target this atypical and potentially tumorigenic fusion kinase. Notes

References

External links

|