|

History of Tonga

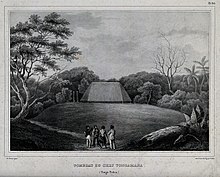

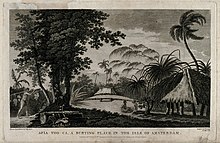

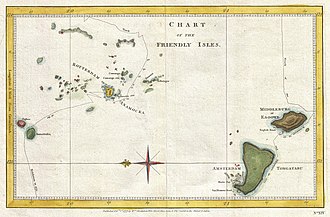

The history of Tonga is recorded since the ninth century BC, when seafarers associated with the Lapita diaspora first settled the islands which now make up the Kingdom of Tonga.[1] Along with Fiji and Samoa, the area served as a gateway into the rest of the Pacific region known as Polynesia.[2] Ancient Tongan mythologies recorded by early European explorers report the islands of 'Ata and Tongatapu as the first islands having been hauled to the surface from the deep ocean by Maui.[3][4] Pre-contactThe dates of the initial settlement of Tonga are still subject to debate; nonetheless, one of the oldest occupied sites is found in the village of Pea on Tongatapu. Radiocarbon dating of a shell found at the site reportedly dates the occupation at 3180 ± 100 BP (Before Present).[5] Some of the oldest sites pertaining to the first occupants of the Tongan Islands are found on Tongatapu which is also where the first Lapita ceramics were found by WC McKern in 1921.[6] Nonetheless, reaching the Tongan islands (without Western navigational tools and techniques) was a remarkable feat accomplished by the Lapita peoples. Not much is known about Tonga before European contact because of the lack of a writing system during prehistoric times other than the oral history told to the early European explorers. The first time the Tongan people encountered Europeans was in April 1616 when Jacob Le Maire and Willem Schouten made a short visit to the islands to trade with them. Early culture  Centuries before Westerners arrived, Tongans created megalithic stoneworks. Most notably, these are the Haʻamonga ʻa Maui and the Langi terraced tombs. The Haʻamonga is 5 meters high and made of three coral-lime stones that weigh more than 40 tons each. The Langi are low, very flat, two or three tier pyramids that mark the graves of former kings. What is known about Tonga before European contact comes from myths, stories, songs, poems (as there was no writing system), as well as from archaeological excavations. Many ancient sites, kitchens and refuse heaps, have been found in Tongatapu and Haʻapai, and a few in Vavaʻu and the Niuas that provide insights into old Tongan settlement patterns, diet, economy, and culture. The Old TongaThe Haʻapai of three thousand years ago was a bit different from the Haʻapai of today. Large flightless birds called megapodes bounded through the tropical rain forest while giant iguanas and various other lizards rested on tree limbs.[7] The skies hosted three different species of fruit bats, three different species of pigeon, and more than two dozen other types of birds. There were no pigs, horses, dogs, cows, or rats. The South Pacific, meanwhile, was almost completely uninhabited. Any present humans existed on the western fringes of the Solomon Islands. Then, around that time, these islanders were suddenly replaced by a new branch of humanity that originated from the Bismarck Archipelago off Papua New Guinea.[8] They intrepidly stormed through the region, rapidly colonizing and pushing east. They brought with them new plant and animal species, as well as a distinct pottery design. Today these people are named the Lapita, after the location in New Caledonia where they were first noticed archaeologically. The Lapita Period  Around 3000 B.P., the Lapita people reached Tonga, and carbon dating places their landfall first in Tongatapu and then in Haʻapai soon after.[9] The newcomers were already well adapted to the resource-scarce island life and settled in small communities of a few households[9] on beaches just above high tide line that faced open lagoons or reefs. Through continued interaction with Lapita relatives of the west, the Haʻapaians obtained domesticated animals and cultivatable plants, but it seems that both of these possible food sources contributed minimally towards their diet for at least the first two hundred years. Instead, they feasted mainly on life in the sea: parrotfish, wrasses, turtles, surgeonfish, jacks, eels, emperors, bottom-dwellers, shellfish, and the occasional deep water tuna.[8] Just as their Polynesian descendants do today. Sea food was inexhaustible, so reefs then were not very different from reefs today, except for the marked decline in sea turtle populations. Fauna didn't fare as well, however, and soon the giant iguanas, the megapodes, twenty four bird species, almost all pigeons, and all but one species of fruit bat were all extinct.[7] They hunted and cooked these animals with the most basic of technologies. When shell pieces were too brittle for tools, they utilized volcanic soils for “andesite/basalt used for adze manufacture and other artifacts such as oils as hammerstones, weaving weights, cooking stones, and decorative pebbles for grave decoration.”[10] If they were lucky, they obtained harder obsidian shards from the far northern fringe volcano of Tafahi in the Niuas.[8] Another useful technology was their eponymous pottery with “dentate” impressions and simple designs that were characteristic of all Lapita settlements in the South Pacific. Tongan Lapita designs were simpler than western Lapita designs, evolving from ornate curvilinear and rectilinear patterns into simple rectilinear forms.[10] The pottery was “slab-built earthenware of andesitic-tephra clay mixed with calcareous or mineral sand tempers and fired at a low temperature.” [10] Decades of archaeological excavations of ancient Lapita kitchens and middens (refuse piles) both in Tongatapu and Haʻapai have taught us much about early Tongan settlement. We know what they ate, what tools they used, where they settled (one colony each on ‘Uiha, Kauvai, and Foa, and two on Lifuka), and how large the settlements were. Despite a wealth of archaeological evidence, however, the Lapita people still stifle us with two main mysteries: How did they spread through the South Pacific so quickly, and why did the Lapita settlers in Tonga quickly abandon their ornate pottery tradition? The Lapitan diaspora began from Papua New Guinea in 1500 BC. By 2850 BP (900 BC) they were already in Tonga, meaning they virtually sprinted east for three hundred years. They travelled in small wooden boats over open ocean to invisible destinations faster than the Europeans colonizers walked across their continent.[8] Archaeologists wonder what would compel people to embark on statistically suicidal missions. It doesn't appear that population pressure was a problem, because most Lapitan islands were sparsely inhabited and could have supported much higher populations, especially if they had turned more towards available root crops. A hypothesis from Kirch is that Lapitan culture encouraged emigration by younger sons.[8] Not just in Tonga, but throughout the South Pacific is a tradition of passing down land to eldest sons. To obtain their own land, younger sons needed to explore. Tangaloa, the chief Tongan god before the arrival of Christianity, was a younger sibling who created Tonga while searching for land from a canoe. His fish hook accidentally caught on a rock on the ocean floor and he was able to pull Tonga to the surface. The other great mystery is why the ornate pottery tradition disappeared, and with such speed. Only two hundred years after arriving, the Lapitan settlers ceased to decorate their earthenware pots at all, and the only thing the leading contemporary Tongan archaeologist can say about the disappearance is that, “Unfortunately most explanations are based on inferential speculation, and they are difficult to validate with any degree of certainty. What we can say with confidence is that, for whatever reason pottery decoration ceased in Tonga, it did so rather suddenly.”[10] The Polynesian Plain Ware Period: 2650–1550 BP (700 BC – 400 AD)Life began to change drastically for Haʻapaians at the same time that ornate pottery was replaced by a strictly utilitarian plain ware kit, and it is at this time that the people may be called Polynesian. Of all the linguistically and traditionally similar people who came to inhabit the triangle created by New Zealand, Hawai’i, and Easter Island, they can all trace ancestry to a few original settlers in Tonga[citation needed]. These original Polynesians in Tonga shifted somewhat away from maritime subsistence towards an increased reliance on agriculture and animal husbandry. Taro, yam, breadfruit, and banana became principal carbohydrate sources, and domesticated animals came to represent much more of the diet.[7] At original Lapita sites, 24% of bird bones came from chickens, which increased after the Polynesian transformation into 81%, marking probably the demise of other bird species as well as an increased reliance on domesticated species.[10] More energy supportive food sources allowed a population explosion. A 25x40 m Lapitan “hamlet” grew into a village over one kilometer in length.[10] Settlement grew around most of the lagoon in Tongatapu and villages finally reached the interior of the main island. Similar expansions have been identified in the Niuas and in Vava’u. To archaeologists, these early Polynesians provide a mystery just as perplexing as the Lapitans. By 1550 BP (400 AD), they ceased to produce any pottery at all. They seem to have turned towards more natural materials instead, and therefore the archaeological record enters into a “dark age”[10] of relatively little information until the emergence of chiefly states hundreds of years later. Speculations as to disappearance of the pottery tradition ranges from the use of coconut cups and bowls that are easier to use, a shift away from steaming shellfish in large bowls to baking in underground ovens, and the unsuitability of Tongan clays for pottery.[10] Nothing can be said with certainty except that the same disappearance also occurred in Fiji and Samoa. The Formative Dark Age: 1550–750 BP (400–1200 AD)Little is known about the period because of the absence of much archaeological evidence. What is clear is that population continued to increase, reaching between 17,000 and 25,000[10] on Tongatapu, and that chiefdoms arose to protect against the increased competition for resources. Tongatapu may have been politically consolidated by a single individual of the future Tuʻi Tonga familial line, as oral tradition traces the king's lineage back through 39 individuals that could have started as early as 1000 bp (950 AD).[10] The maritime empire made famous by oral tradition, however did not begin until after 750 BP (1200 AD). Tongan Maritime Empire  By the 12th century, Tongans, and the Tongan kings named the Tu'i Tonga, were known across the Pacific, from Niue, Samoa to Tikopia. They ruled these nations for more than 400 years, sparking some historians to refer to a "Tongan Empire", although it was more of a network of interacting navigators, chiefs, and adventurers. It is unclear whether chiefs of the other islands actually came to Tonga regularly to acknowledge their sovereign. Distinctive pottery and Tapa cloth designs also show that the Tongans have travelled to Fiji and Hawaii.[11] In 950 AD Tu'i Tonga 'Aho'eitu started to expand his rule outside of Tonga. According to leading Tongan scholars, including Okusitino Mahina, the Tongan and Samoan oral traditions indicate that the first Tu'i Tonga was the son of their god Tangaloa.[12] As the ancestral homeland of the Tu'i Tonga dynasty and the abode of deities such as Tagaloa 'Eitumatupu'a, Tonga Fusifonua, and Tavatavaimanuka. By the time it comes to the 10th Tu’i Tonga Momo, and his successor, ‘Tu’itatui, the empire had already stretched from Tikopia in the west to Niue in the east.[13] Their realm contained Wallis and Futuna, Tokelau, Tuvalu, Rotuma, Nauru, parts of Fiji, parts of the Solomon Islands, Kiribati, Niue, and parts of Samoa.[13] However, some islands in Polynesia were left alone by the Tu'i Tonga such as, parts of Tahiti Nui, The Cook Islands, and the Marquesas. To better govern the large territory, the Tu’i Tongas had their throne moved by the lagoon at Lapaha, Tongatapu. The influence of the Tu’i Tonga was renowned throughout the Pacific, and many of the neighboring islands participated in the widespread trade of resources and new ideas. Under the 10th Tuʻi Tonga, Momo and his son Tuʻitātui (11th Tuʻi Tonga) the empire was at its height of expansion, tributes for the Tu'i Tonga were said to be exacted from all tributary chiefdoms of the empire. This tribute was known as the " 'Inasi " and was conducted annually at Mu'a following the harvest season when all countries that were subject to the Tu'i Tonga must bring a gift for the gods, who was recognized as the Tu'i Tonga.[14] Captain Cook witness an Inasi ceremony in 1777, in which he noticed a lot of foreigners in Tonga, especially the darker people that resembles African descend from Fiji, Solomon Islands [citation needed] and Vanuatu.[11] The finest mats of Samoa ('ie toga) are incorrectly translated as "Tongan mats;" the correct meaning is "treasured cloth" ("ie" = cloth, "toga" = female goods, in opposition to "oloa" = male goods).[15] Many fine mats came into the possession of the Tongan royal families through chiefly marriages with Samoan noblewomen, such as Tohu'ia the mother of Tu'i Kanokupolu Ngata who came from Safata, 'Upolu, Samoa. These mats, including the Maneafaingaa and Tasiaeafe, are considered the crown jewels of the current Tupou line[16] (which is derived matrilineally from Samoa).[17] The success of the Empire was largely based upon the Imperial Navy. The most common vessels were long-distance double-canoes fitted with triangular sails. The largest canoes of the Tongan kalia type could carry up to 100 men. The most notable of these were the Tongafuesia, ʻĀkiheuho, the Lomipeau, and the Takaʻipōmana. It should be mentioned that the Takaʻipōmana was actually a Samoan kalia; according to Queen Salote and the Palace Records this was the Samoan double-canoe that brought Tohu'ia Limapō from Samoa to wed the Tu'i Ha'atakalaua.[17] The large navy allowed for Tonga to become wealthy with large amounts of trade and tribute flowing into the Royal Treasury.[11] The Tuʻi Tonga decline began due to numerous wars and internal pressure. In the 13th or 14th century Samoa defeated Tu'i Tonga Talakaifaiki under the lead of the Malietoa family. In response the falefā was created as political advisors to the Empire. The falefā officials were initially successful in maintaining some hegemony over other subjected islands but increased dissatisfaction led to the assassination of several rulers in succession. The most notable were, Havea I (19th TT), Havea II (22nd TT), and Takalaua (23rd TT), who were all known for their tyrannical rule. In AD 1535, Takalaua was assassinated by two foreigners while swimming in the lagoon of Mu'a. His successor, Kauʻulufonua I pursued the killers all the way to ʻUvea, where he killed them.[18]  Because of so many assassination attempts on the Tu'i Tonga, Kauʻulufonua established a new dynasty called Tu'i Ha'atakalaua in honor of his father and he gave his brother Mo’ungamotu’a, the title of Tu’i Ha’a Takalaua. This new dynasty was to deal with the everyday decisions of the empire, while the position of Tu’i Tonga was to be the nation's spiritual leader, though he still controlled the final say in the life or death of his people. The Tu'i Tonga "empire" at this period becomes Samoan in orientation as the Tu'i Tonga kings themselves became ethnic Samoans who married Samoan women and resided in Samoa.[20] Kau'ulufonua's mother was a Samoan from Manu'a,[21] Tu'i Tonga Kau'ulufonua II and Tu'i Tonga Puipuifatu had Samoan mothers and as they married Samoan women the succeeding Tu'i Tongas - Vakafuhu, Tapu'osi, and 'Uluakimata - were allegedly more "Samoan" than "Tongan."[22] In 1610, the 6th Tu’i Ha’a Takalaua, Mo'ungatonga, created the position of Tu’i Kanokupolu for his half-Samoan son, Ngata, which divided regional rule between them, though as time went on the Tu’i Kanokupolu's power became more and more dominant over Tonga. The Tu'i Kanokupolu dynasty oversaw the importation and institution of many Samoan policies and titles and according to Tongan scholars this Samoanized form of government and custom continues today in the modern Kingdom of Tonga [23] Things continued this way for a long time afterward. The first Europeans arrived in 1616, when the Dutch explorers Willem Schouten and Jacob Le Maire spotted Tongans in a canoe off the coast of Niuatoputapu,[24] followed by Abel Tasman who passed by the islands on 20 January 1643.[25] These visits were brief, however, and did not significantly change the island.[24][25] Captain James Cook observed and recorded his accounts of the Tuʻi Tonga kings during his visits to Tonga.[26][27][28] The dividing line between the two moieties was the old coastal road named Hala Fonua moa (dry land road). Still today the chiefs who derive their authority from the Tuʻi Tonga are named the Kau hala ʻuta (inland road people) while those from the Tuʻi Kanokupolu are known as the Kau hala lalo (low road people). Concerning the Tuʻi Haʻatakalaua supporters: when this division arose, in the 15th century, they were of course the Kauhalalalo. But when the Tuʻi Kanokupolu had overtaken them they shifted their allegiance to the Kauhalaʻuta. Modern archeology, anthropology and linguistic studies confirm widespread Tongan cultural influence ranging widely[29][30] through East 'Uvea, Rotuma, Futuna, Samoa and Niue, parts of Micronesia (Kiribati, Pohnpei), Vanuatu, and New Caledonia and the Loyalty Islands,[31] and while some academics prefer the term "maritime chiefdom",[32] others argue that, while very different from examples elsewhere, "..."empire" is probably the most convenient term."[33] European arrival and Christianization  In the 15th century and again in the 17th, civil war erupted. It was in this context that the first Europeans arrived, beginning with Dutch explorers Willem Schouten and Jacob Le Maire. Between April 21 to 23, 1616 they moored at the Northern Tongan islands "Cocos Island" (Tafahi) and "Traitors Island" (Niuatoputapu), respectively. The kings of both of these islands boarded the ships and Le Maire drew up a list of Niuatoputapu words, a language now extinct. On April 24, 1616, they tried to moor at the "Island of Good Hope" (Niuafo'ou), but a less welcoming reception there made them decide to sail on. On January 21, 1643, the Dutch explorer Abel Tasman was the first European to visit the main island (Tongatapu) and Haʻapai after rounding Australia and New Zealand while looking for a faster route to Chile. He mapped several islands. Tasman named the island of Tongatapu t’ Eijlandt Amsterdam (Amsterdam Island), because of its abundance of supplies.[34] This name is no longer used except by historians. The most significant impact had the visits of Captain Cook in 1773, 1774, and 1777, followed by the first London missionaries in 1797, and the Wesleyan Methodist Walter Lawry in 1822. Around that time, most Tongans converted en masse to the Wesleyan (Methodist) or Catholic faiths. Other denominations followed, including Pentecostals, Mormons, Seventh-day Adventists, and most recently the Bahá'í faith. The islands were also visited by the Spanish under Francisco Antonio Mourelle in 1781 and Alessandro Malaspina (who unsuccessfully claimed Vavau for Spain) in 1793 and by the French under Marc-Joseph Marion du Fresne in 1772, Jean-François de Galaup, comte de Lapérouse in 1787 and Antoine Bruni d'Entrecasteaux in 1793.[35] Fletcher Christian also led the mutiny on the Bounty while crossing Tongan waters, in 1789.

Unification In 1799, the 14th Tuʻi Kanokupolu, Tukuʻaho was murdered, which sent Tonga into a civil war for fifty years. Finally, the islands were united into a Polynesian kingdom in 1845 by the ambitious young warrior, strategist, and orator Tāufaʻāhau. He held the chiefly title of Tu'i Kanokupolu, but was baptised with the name King George Tupou I. In 1875, with the help of missionary Shirley Baker, he declared Tonga a constitutional monarchy, at which time he emancipated the serfs, enshrined a code of law, land tenure, and freedom of the press, and limited the power of the chiefs. The islands were not fully surveyed until 1898, when the British warships HMS Egeria (1873) and HMS Penguin (1876) completed the task.[35]

20th century  Kingdom of Tonga (1900–1970)Tonga became a British protected state under a Treaty of Friendship on May 18, 1900, when European settlers and rival Tongan chiefs tried to oust the second king. The Treaty of Friendship and protected state status ended in 1970 under arrangements established prior to her death by the third monarch, Queen Sālote. On 18 May 1900, to discourage German advances,[36] the Kingdom of Tonga became a Protected State with the United Kingdom under a Treaty of Friendship signed by George Tupou II after European settlers and rival Tongan chiefs attempted to overthrow him.[37][38] Foreign affairs of the Kingdom of Tonga were conducted through the British Consul. The United Kingdom had veto power over foreign policies and finances of the Kingdom of Tonga.[36] Tonga was affected by the 1918 flu pandemic, with 1,800 Tongans killed, around eight percent of the residents.[39] For most of the 20th century Tonga was quiet, inward-looking, and somewhat isolated from developments elsewhere in the world. Tonga's complex social structure is essentially broken into three tiers: the king, the nobles, and the commoners. Between the nobles and commoners are Matapule, sometimes called "talking chiefs," who are associated with the king or a noble and who may or may not hold estates. Obligations and responsibilities are reciprocal, and although the nobility are able to extract favors from people living on their estates, they likewise must extend favors to their people. Status and rank play a powerful role in personal relationships, even within families.

World War IIUpon the British declaration of war against Germany in 1939, the government of Tonga issued a declaration "placing all of its resources at the disposal of the British" and formally declared war against Germany in its own right(since the British control Tonga's external affairs, it coerce Tonga to declare war on Germany). Queen Sālote directed the re-establishment of the national militia and donated 160 acres (65 ha) to the British for the construction of an airfield. The people of Tonga subsequently raised enough funds to buy three Spitfires for the Royal Air Force.[40] In August 1941, Sālote proclaimed a national day of prayer for the British war effort.[41] In mid-1941, the New Zealand Army despatched 70 military advisors to Nuku'alofa to train the Tongan Defence Force. Following the attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, Tonga also declared war on Japan. In anticipation of a Japanese invasion, citizens were evacuated from Nuku'alofa and barbed wire and trenches were erected on the beaches of Tongatapu.[42] Independence (1970)  On 4 June 1970, protected state status ended under arrangements established prior to her death in 1965 by the third monarch, Queen Sālote. Tonga joined the Commonwealth of Nations in 1970, and the United Nations in 1999. While exposed to colonial forces, Tonga has never lost indigenous governance, a fact that makes Tonga unique in the Pacific and boosts confidence in the monarchical system. The British High Commission in Tonga closed in March 2006. Tonga's current king, Tupou VI, traces his line directly back through six generations of monarchs. The previous king, George Tupou V, born in 1946, continued to have ultimate control of the government until August 2008. At that point, concerns over financial irregularities and calls for democracy led to his relinquishing most of his day-to-day powers over the government.[43] Tongans are beginning to confront the problem of how to preserve their cultural identity and traditions in the wake of the increasing impact of Western technology and culture. Migration and the gradual monetization of the economy have led to the breakdown of the traditional extended family. Some of the poor, once supported by the extended family, are now being left without visible means of support. Educational opportunities for young commoners have advanced, and their increasing political awareness has stimulated some dissent against the nobility system. In addition, the rapidly increasing population is already too great to provide the constitutionally mandated 8.25 acre (33,000 m2) API for each male at age 16. In mid-1982, the population density was 134 persons per square kilometer. Because of these factors, there is considerable pressure to move to the Kingdom's only urban center. 21st century

2002 electionIn the March 2002 election, supporters of the Human Rights and Democracy Movement (HRDM) won seven of the nine popularly-elected seats for people's representatives, with the remaining two representing "traditionalist" values. Voter turnout was 48.9%.[44] The nine nobles and all the cabinet ministers that sit in the Legislative Assembly generally support the government. Following the election, HRDM leader 'Akilisi Pohiva was arrested and charged with sedition over an article published in his newspaper Kele’a alleging the king had a secret fortune,[45] but was later acquitted by a jury.[46] In 2003, the Taimi 'o Tonga (Tongan Times), a newspaper published in New Zealand in the Tongan language that had been critical of the government was prohibited from distribution in Tonga due to government objections to its political content. After the newspaper obtained two court orders, it was again distributed freely. A Media Operators Bill and constitutional amendment, intended to restrict media freedom in Tonga, was hotly debated in 2003. The legislation allowed the government to exert control over coverage of "cultural" and "moral" issues, ban publications it deemed offensive, and ban foreign ownership of the media. In October 2003, thousands of Tongans marched peacefully through the streets of the capital city Nukuʻalofa in an unprecedented demonstration against the government's plans to limit media freedom. Despite the protests, the Media Operators Bill and constitutional amendment passed the Legislature and as of December 2003 needed only the King's signature to become law. By February 2004, the amendment was passed and licensure of news media was required. Those papers denied licenses under the new act included the Taimi 'o Tonga (Tongan Times), the Kele'a and the Matangi Tonga, while those permitted licenses were uniformly church based or pro-government. Further opposition to government action included calls by the Tu'i Pelehake (a prince, nephew of the King and elected member of parliament) for Australia and other nations to pressure the Tongan government to democratize the electoral system, and a legal writ calling for a judicial investigation of the bill. The latter was supported by some 160 people, including 7 of the 9 elected "People's Representatives". 2005 election At the 2005 Tongan general election, the Human Rights and Democracy Movement won seven of the nine popularly-elected seats (the rest of the 30 MPs are appointed by the King or are members of the Tongan aristocracy). 'Aho'eitu 'Unuaki'otonga Tuku'aho, son of the King, initially retained his position as Prime Minister, but he resigned in 2006, after the Tongan Speaker of the House was found guilty of bribery.[47] The position passed to Feleti Sevele, Minister of Labour and one of the two independent candidates elected, as well as the first non-noble Prime Minister of the country. In 2005 the government spent several weeks negotiating with striking civil service workers before reaching a settlement. A constitutional commission met in 2005–2006 to study proposals to update the constitution. A copy of the commission's report was presented to King Taufa'ahau Tupou IV, shortly before his death in September 2006. 2006 riots  Tonga did not rate as an "electoral democracy" under the criteria of Freedom House's Freedom in the World 2006 report. This is likely because while elections exist, they could only elect nine of 30 Legislative Assembly seats, the remainder being selected either by the nobility or the government; as such the people have a voice in but no control over the government. The public expected democratic changes from the new monarch. On November 16, 2006, rioting broke out in the capital city of Nukuʻalofa when it seemed that the parliament would adjourn for the year without having made any advances in increasing democracy in government. Government buildings, offices, and shops were looted and burned[48] Eight people died in the riots.[49] The government agreed that elections would be held in 2008 in which a majority of the parliament would be elected by popular vote.[50] A state of emergency was declared on November 17, with emergency laws giving security forces the right to stop and search people without a warrant.[51] On 18 January 2007 Pōhiva was arrested[52] and charged with sedition[53] over his role in the 2006 Nuku'alofa riots. 2008 electionThe April 2008 elections saw a 48% turnout to elect the nobles' representatives and the 9 people's representatives. Most of the pro-democracy MPs were reconfirmed, despite several facing charges of sedition over the 2006 Nuku'alofa riots[54] All nine elected MPs were pro-democracy activists.[55] About two weeks before the election, it was announced that the Tonga Broadcasting Commission would henceforth censor candidates' political broadcasts,[56] and that TBC reporters would be banned from reporting on political matters.[57] Tonga Review criticised the decision as an undue restriction on freedom of speech.[58] On 29 May 2008, in the speech from the throne at the opening of Parliament, Princess Regent, Salote Mafile'o Pilolevu Tuita announced that the government would introduce a political reform bill by June 2008, and that the current term of Parliament would be the last one under the current constitution[59] In July 2008, three days before his coronation, King George Tupou V announced that he would relinquish most of his power and be guided by his Prime Minister's recommendations on most matters, following upcoming elections.[43] In November 2009, a constitutional review panel recommended a ceremonial monarchy stripped of real political power and to invest political power in a completely elected Legislative Assembly of Tonga (the Fale Alea) which, up to this point was largely hereditary due to the fact that most of the seats where designated for the nobles.[60][61] and were preceded by a programme of constitutional reform.[62] Democratisation and 2010 electionsIn April 2010 the Legislative Assembly enacted a package of political reforms towards a fully representative democracy, increasing the number of directly elected people's representatives from 9 to 17,[63] with ten seats for Tongatapu, three for Vavaʻu, two for Haʻapai and one each for Niuas and ʻEua.[64] All of the seats are single-seat constituencies, as opposed to the multi-member constituencies used before. These changes mean that 17 out of 26 representatives (65.4%) would be directly elected, up from 9 out of 30 (30.0%).[65][66] The aristocracy would still select its nine representatives, while all remaining seats, which were previously appointed by the monarch, would be abolished.[66] Early general elections under the new electoral law were held on 25 November 2010.[67] The Taimi Media Network described the 2010 Tongan Legislative Assembly as "Tonga’s first democratically elected Parliament".[68] The Democratic Party of the Friendly Islands (DPFI), founded in September 2010 specifically to fight the election and led by veteran pro-democracy campaigner 'Akilisi Pohiva, secured the largest number of seats, with 12 out of the seventeen "people's representative" seats.[69] ʻAkilisi Pohiva, the MP for Tongatapu 1, had sought to become Prime Minister, but the nobles and independent MP entrusted Lord Tuʻivakanō with the task of forming a government, relegating the DPFI to the status of a de facto parliamentary opposition.[70] The DPFI put forward bills for further democratisation, including the proposal of direct election of the Prime Minister from among the 26 elected MPs, as well as of universal suffrage for all 26 MPs. These proposals were not taken forward by the conservative majority.[71][72] At the death of King George Tupou V on 18 March 2012, his son ʻAhoʻeitu ʻUnuakiʻotonga Tukuʻaho became King of Tonga, with the regnal name ʻAhoʻeitu Tupou VI. New elections in 2014 saw the DPFI lose three seats to independent candidates. Its leader Pohiva was nevertheless appointed as new Prime Minister of Tonga. On August 25, 2017 Pohiva was dismissed by the King along with the rest of parliament with fresh elections to be held on November 16. The Elections resulted in the DPFI winning 14 seats - enough for Pohivia to form government without relying on nobles' or independent MPs.[73][74] 2022 tsunamiOn 15 January 2022 a tsunami caused by an eruption of the Hunga Tonga–Hunga Haʻapai volcano swept through many parts of Tonga. It killed four people in Tonga and two others in Peru.[75][76] Many places in Australia and other countries were also put on high alert.[77] See also

References

Further reading

External links |