|

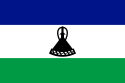

Lesotho

Lesotho (/lɪˈsuːtuː/ ⓘ lih-SOO-too,[6][7] Sotho pronunciation: [lɪˈsʊːtʰʊ]), formally the Kingdom of Lesotho, formerly known as Basutoland, is a landlocked country in Southern Africa. As an enclave of South Africa, with which it shares a 1,106 km (687 mi) border,[8] it is the largest sovereign enclave in the world, and the only one outside of the Italian Peninsula. It is situated in the Maloti Mountains and contains the highest peak in Southern Africa.[9] It has an area of over 30,000 km2 (11,600 sq mi) and has a population of about two million. Its capital and largest city is Maseru. The country is also known by the nickname The Mountain Kingdom/The Kingdom in the Sky.[10] The Sotho ethnic group (also known as Basotho), from which the country derives its name, composes 99.7% of the country's current population, making it one of the most ethnically homogeneous in the world. Their native language, Sesotho, is the official language along with English. The name Lesotho translates to "land of the Sesotho speakers".[11][12] Lesotho was formed in 1824 by King Moshoeshoe I. Continuous encroachments by Dutch settlers made the King enter into an agreement with the British Empire to become a protectorate in 1868 and, in 1884, a crown colony. It achieved independence in 1966, and was subsequently ruled by the Basotho National Party (BNP) for two decades. Its constitutional government was restored in 1993 after seven years of military rule. King Moshoeshoe II was exiled in 1990 but returned in 1992 and was reinstated in 1995. One year later, Moshoeshoe II died and his son Letsie III took the throne, which he still holds.[8] Lesotho is considered a lower middle income country with significant socioeconomic challenges. Almost half of its population is below the poverty line, and the country's HIV/AIDS prevalence rate is the second-highest in the world. However, it also targets a high rate of universal primary education and has one of the highest rates of literacy in Africa (81% as of 2021). Lesotho is a member of the United Nations, the Non-Aligned Movement, the Commonwealth of Nations, the African Union, and the Southern African Development Community. According to 2023 V-Dem Democracy indices, Lesotho is ranked 64th electoral democracy worldwide and 7th electoral democracy in Africa.[13] History

Basotho land Basutoland emerged as a single polity under King Moshoeshoe I in 1822. Moshoeshoe, a son of Mokhachane, a minor chief of the Bakoteli lineage, formed his own clan and became a chief around 1804. Between 1820 and 1823, he and his followers settled at the Butha-Buthe Mountain, joining with former adversaries in resistance against the Lifaqane associated with the reign of Shaka Zulu from 1818 to 1828. Further evolution of the state emerged from conflicts between British and Dutch colonists leaving the Cape Colony following its seizure from the French-allied Dutch by the British in 1795, and also from the Orange River Sovereignty and subsequent Orange Free State. Missionaries Thomas Arbousset, Eugène Casalis and Constant Gosselin from the Paris Evangelical Missionary Society, invited by Moshoeshoe I, were placed at Morija, developing Sesotho orthography and printed works in the Sesotho language between 1837 and 1855. Casalis, acting as translator and providing advice on foreign affairs, helped set up diplomatic channels and acquire guns for use against the encroaching Europeans and the Griqua people. Trekboers from Cape Colony arrived on the western borders of Basutoland and claimed rights to its land, the first of which being Jan de Winnaar who settled in the Matlakeng area in 1838. Incoming Boers attempted to colonise the land between the two rivers and north of the Caledon, claiming that it had been abandoned by the Sotho people. Moshoeshoe subsequently signed a treaty with the British Governor of the Cape Colony, Sir George Thomas Napier, that annexed the Orange River Sovereignty where Boers had settled. These outraged Boers were suppressed in a skirmish in 1848. In 1851, a British force was defeated by the Basotho army at the city of Kolonyama. After repelling another British attack in 1852, Moshoeshoe sent an appeal to the British commander that settled the dispute diplomatically, and then defeated the Batlokoa in 1853. In 1854, the British pulled out of the region, and in 1858, Moshoeshoe fought a series of wars with the Boers in what is known as the Free State–Basotho War. As a result, Moshoeshoe lost a portion of the western lowlands. The last war with the Boers ended in 1867 when Moshoeshoe appealed to Queen Victoria who agreed to make Basutoland a British protectorate in 1868.  In 1869, the British signed a treaty at Aliwal North with the Boers that defined the boundaries of Basutoland. This treaty reduced Moshoeshoe's kingdom to half its previous size by ceding the western territories. Then, the British transferred functions from Moshoeshoe's capital in Thaba Bosiu to a police camp on the northwest border, Maseru, until eventually the administration of Basutoland was transferred to the Cape Colony in 1871. Moshoeshoe died on 11 March 1870, marking the beginning of the colonial era of Basutoland. In the Cape Colony period between 1871 and 1884, Basutoland was treated similarly to other territories that had been forcibly annexed, much to the humiliation of the Basotho, leading to the Basuto Gun War in 1880–1881.[14][15] In 1884, the territory became a Crown colony by the name of Basutoland, with Maseru as its capital. It remained under direct rule by a governor, while effective internal power was wielded by tribal chiefs. In 1905, a railway line was built to connect Maseru to the railway network of South Africa. IndependenceBasutoland gained its independence from the United Kingdom and became the Kingdom of Lesotho in 1966.[16] The Basotho National Party (BNP) ruled from 1966 until January 1970. What later ensued was a de facto government led by Leabua Jonathan. In January 1970, the ruling BNP lost the first post-independence general elections, with 23 seats to the Basotho Congress Party's (BCP) 36. Prime Minister Jonathan refused to cede power to BCP, instead declaring himself prime minister and imprisoning the BCP leadership. BCP began a rebellion and then received training in Libya for its Lesotho Liberation Army (LLA) under the pretense of being Azanian People's Liberation Army soldiers of the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC). Deprived of arms and supplies by the David Sibeko faction of PAC in 1978, the 178-strong LLA was rescued from their Tanzanian base by the financial assistance of a Maoist PAC officer and launched a guerrilla war. A force was defeated in northern Lesotho, and later guerrillas launched more sporadic attacks. The campaign was compromised when BCP's leader, Ntsu Mokhehle, went to Pretoria. In the 1980s, some Basotho who sympathised with the exiled BCP were threatened with death and attacked by the government of Leabua Jonathan. On 4 September 1981, the family of Benjamin Masilo was attacked. In the attack his 3-year-old grandson died. Four days later, Edgar Mahlomola Motuba, the editor of the newspaper Leselinyana la Lesotho, was abducted from his home, together with two friends, and murdered.  After Jonathan was sacked in a 1986 coup, the Transitional Military Council that came to power granted executive powers to King Moshoeshoe II, who was until then a ceremonial monarch. In 1987 the king was forced into exile after coming up with a 6-page memorandum on how he wanted the Lesotho's constitution to be, which would have given him more executive powers than the military government had originally agreed to. His son was installed as King Letsie III in his place. The chairman of the military junta, Major General Justin Metsing Lekhanya, was ousted in 1991 and replaced by Major General Elias Phisoana Ramaema who handed over power to a democratically elected government of BCP in 1993. Moshoeshoe II returned from exile in 1992 as an ordinary citizen. After the return to democratic government, King Letsie III tried unsuccessfully to persuade the BCP government to reinstate his father (Moshoeshoe II) as head of state. In August 1994, Letsie III staged a military-backed coup that deposed the BCP government, after the BCP government refused to reinstate his father, Moshoeshoe II, according to Lesotho's constitution. Member states of the Southern African Development Community (SADC) engaged in negotiations to reinstate the BCP government. One of the conditions Letsie III put forward for this was that his father should be re-installed as head of state. After protracted negotiations, the BCP government was reinstated and Letsie III abdicated in favour of his father in 1995, and ascended the throne again when Moshoeshoe II died at the age of 57 in a supposed road accident when his car plunged off a mountain road on 15 January 1996. According to a government statement, Moshoeshoe had set out at 1 am to visit his cattle at Matsieng and was returning to Maseru through the Maluti Mountains when his car left the road.[17] In 1997, the ruling BCP split over leadership disputes. Prime Minister Ntsu Mokhehle formed a new party, the Lesotho Congress for Democracy (LCD), and was followed by a majority of members of parliament, which enabled him to form a new government. Pakalitha Mosisili succeeded Mokhehle as party leader and LCD won the general elections in 1998. Opposition protests "intensified", culminating in a demonstration outside the royal palace in August 1998. While the Botswana Defence Force troops were welcomed, tensions with South African National Defence Force troops resulted in fighting. Incidences of rioting "intensified" when South African troops hoisted a South African flag over the Royal Palace. By the time the SADC forces withdrew in May 1999, much of the capital of Maseru "lay in ruins", and the southern provincial capital towns of Mafeteng and Mohale's Hoek had lost over a third of their commercial real estate. An Interim Political Authority (IPA), charged with reviewing the electoral structure in the country, was created in December 1998. IPA devised a proportional electoral system to ensure that the opposition would be represented in the National Assembly. The new system retained the existing 80 elected Assembly seats, and added 40 seats to be filled on a proportional basis. Elections were held under this new system in May 2002, and LCD won, gaining 54% of the vote. There are irregularities and threats of violence from Major General Lekhanya. Nine opposition parties hold all 40 of the proportional seats, with BNP having the largest share (21). LCD has 79 of the 80 constituency-based seats.[18] While its elected members participate in the National Assembly, BNP has launched legal challenges to the elections, including a recount. On 30 August 2014, an alleged abortive military "coup" took place, forcing then Prime Minister Thomas Thabane to flee to South Africa for three days.[19][20] On 19 May 2020, Thomas Thabane formally stepped down as prime minister of Lesotho following months of pressure after he was named as a suspect in the murder of his ex-wife.[21] Moeketsi Majoro, the economist and former Minister of Development Planning, was elected as Thabane's successor.[22] On 13 May 2020, according to the health ministry, Lesotho became the last African nation to report a COVID-19 case.[23] On 28 October 2022, Sam Matekane was sworn in as Lesotho's new Prime Minister after forming a new coalition government. His Revolution for Prosperity (RFP) party, formed earlier same year, won the 7 October elections.[24] PoliticsThe Lesotho Government is a parliamentary constitutional monarchy. The Prime Minister, Sam Matekane, is the head of government and has executive authority. The King of Lesotho, Letsie III, is the head of state and serves a "largely ceremonial function"; he no longer possesses any executive authority and is prohibited from actively participating in political initiatives. The Revolution for Prosperity leads a coalition government in the National Assembly, the lower house of parliament. The upper house of parliament, the Senate, is composed of 22 principal chiefs whose membership is hereditary, and 11 appointees of the king, acting on the advice of the prime minister. The constitution provides for an independent judicial system, made up of the High Court, the Court of Appeal, Magistrate's Courts, and traditional courts that exist predominantly in rural areas. All but one of the Justices on the Court of Appeal are South African jurists. There is no trial by jury; rather, judges make rulings alone or, in the case of criminal trials, with two other judges as observers. The constitution protects some civil liberties, including freedom of speech, freedom of association, freedom of the press, freedom of peaceful assembly, and freedom of religion. Lesotho was ranked 12th out of 48 sub-Saharan African countries in the 2008 Ibrahim Index of African Governance.[25] In 2010, the People's Charter Movement called for the practical annexation of the country by South Africa due to the HIV epidemic. Nearly a quarter of the population tests positive for HIV.[26] The country has faced economic collapse, a weaker currency, and travel documents restricting movement. An African Union report called for economic integration of Lesotho with South Africa and stopped short of suggesting annexation. In May 2010, the Charter Movement delivered a petition to the South African High Commission requesting integration. South Africa's home affairs spokesman Ronnie Mamoepa rejected the idea that Lesotho should be treated as a special case.[27] At the peak of the AIDS epidemic, over 30,000 Lesotho residents signed a petition for the country to be annexed to prevent life expectancy from falling to 34 years old.[28] Scholars of comparative politics, like in Jeffrey Herbst's "War and the State of Africa", argue that the lack of border disputes for countries like Lesotho and Eswatini has kept the countries weak politically.[29] This weakness stems from the remnants of colonialism in the government, influenced by English and Roman-Dutch common law.[30] As a result, the government was not made to serve the Basotho people but rather to be exploitative. After prime minister Tom Thabane resigned due to impeachment threats and a warrant of arrest for the murder of his wife in 2020, the South African finance minister suggested a confederation between Lesotho, Eswatini, and South Africa as a solution.[31] His successor, Moeketsi Majoro, held office from 2020 to 2022 until he similarly resigned[32] after a vote of "no-confidence" in Parliament for misconduct with the military and improperly handling COVID-19.[33] While prime minister Sam Matekane is working with the South African Development Community (SADC) towards legal reform, his administration still shows signs of corruption, as 40,000 garment workers protested for better conditions and faced excessive force that killed two protestors.[34] Foreign relationsLesotho is a member of some regional economic organisations, including the Southern African Development Community (SADC)[35] and the Southern African Customs Union (SACU).[36] It is active in the United Nations (UN), the African Union (AU), the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM), the Commonwealth, and other international organisations.[37] Lesotho has maintained ties with the United Kingdom (Wales in particular), Germany, the United States, and other Western states. It broke relations with China and re-established relations with Taiwan in 1990, and later restored ties with China. It recognises the State of Palestine.[38] From 2014 up until 2018, it recognised the Republic of Kosovo.[39] It was a public opponent of apartheid in South Africa and granted a number of South African refugees political asylum during the apartheid era.[38] In 2019, it signed the UN treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons.[40] Defence and law enforcementThe Lesotho Defence Force (LDF) is charged with the maintenance of internal security and the defence of Lesotho. Its chief officer is designated Commander.[41] The Lesotho Mounted Police Service (LMPS) is charged with the maintenance of law and order. Its chief officer is designated Commissioner. LMPS provides uniformed policing, criminal detection, and traffic policing. There are specialist units dealing with high-tech crime, immigration, wildlife, and terrorism. The force has existed, with changes of name, continuously since 1872. The Lesotho National Security Service (LNSS) is charged with the protection of national security. Established in modern form by the National Security Services Act of 1998, its chief officer is designated Director General, and appointed and dismissed by the Prime Minister.[42] LNSS is an intelligence service, part of the Ministry of Defence and National Security, and reporting directly to the Government.[43] Law The Constitution of Lesotho came into force after the publication of the Commencement Order. Constitutionally, legislation refers to laws that have been passed by both houses of parliament and have been assented to by the king (Section 78(1)). Subordinate legislation refers to laws passed by other bodies to which parliament has, by virtue of Section 70(2) of the Constitution, validly delegated such legislative powers. These include government publications, ministerial orders, ministerial regulations, and municipal by-laws. While Lesotho shares with South Africa, Botswana, Eswatini, Namibia, and Zimbabwe a mixed general legal system which resulted from the interaction between the Roman-Dutch civil law and the English common law. Its general law operates independently. Lesotho applies the common law, which refers to unwritten law or law from non-statutory sources, and excludes customary law. Decisions from South African courts are only persuasive, and courts refer to them in formulating their decisions. Decisions from some jurisdictions can be cited for their persuasive value. Magistrates' court decisions do not become precedent since these are lower courts. They are bound by the decisions of the High Court and the Court of Appeal. The Court of Appeal, the final appellate forum on all matters, has supervisory and review jurisdiction over all the courts of Lesotho. Lesotho has a dual legal system consisting of customary and general laws operating side by side. Customary law is made up of the customs of the Basotho, written and codified in the Laws of Lerotholi. The general law consists of Roman Dutch law imported from the Cape and the Lesotho statutes. The codification of customary law came about after a council was appointed in 1903 to advise the British Resident Commissioner on which laws would be best for governing the Basotho. Until this time, the Basotho customs and laws were passed down from generation to generation through oral tradition. The council was given the task of codifying them, and they came up with the Laws of Lerotholi which are then applied by customary courts (local courts). The written works of certain authors have persuasive value in the courts of Lesotho. These include the writings of the "old authorities as well as contemporary writers from similar jurisdictions". Districts For administrative purposes, Lesotho is divided into 10 districts, each headed by a district administrator. Each district has a capital known as a camptown. The districts are subdivided into 80 constituencies, which consist of 129 local community councils. Geography  Lesotho covers 30,355 km2 (11,720 sq mi). It is the only independent state in the world that lies entirely above 1,000 metres (3,281 ft) in elevation. Its lowest point of 1,400 metres (4,593 ft) is thus the highest lowest point of any country in the world. Over 80% of the country lies above 1,800 metres (5,906 ft). Lesotho is the southernmost landlocked country in the world. It is the largest of the world's three independent states completely surrounded by the territory of another country, with Vatican City and San Marino being the other two. It is the only such state outside the Italian peninsula and Europe, as well as the only one that is not a microstate. Lesotho lies between latitudes 28° and 31°S, and longitudes 27° and 30°E. About 12% of Lesotho is arable land which is vulnerable to soil erosion; it is estimated that 40 million tons of soil are lost each year due to erosion.[44] ClimateBecause of its elevation, Lesotho remains cooler throughout the year than other regions at the same latitude. Most of the rain falls as summer thunderstorms. Maseru and surrounding lowlands may reach 30 °C (86 °F) in summer. The temperature in the lowlands can get down to −7 °C (19 °F) and the highlands to −18 °C (0 °F) at times. Snow is more common in the highlands between May and September; the higher peaks may experience snowfalls year-round. Rainfall in Lesotho is variable regarding both when and where precipitation occurs. Annual precipitation can vary from 500 mm annually in one area to 1200 mm in another because of elevation.[44] The summer season that stretches from October to April sees the most rainfall, and from December to February, the majority of the country receives over 100 mm of rain a month.[44] The least monthly rainfall in Lesotho occurs in June when most regions receive less than 15 mm a month.[44] Drought Periodic droughts have an effect on Lesotho's majority rural population as some people living outside of urban areas rely on subsistence farming or small scale agriculture as their primary source of income.[45] Droughts in Lesotho are exacerbated by some agricultural practices.[46] The World Factbook lists periodic droughts under the 'Natural Hazard' section of Lesotho's section of the publication.[8] In 2007, Lesotho experienced a drought and was advised by the United Nations to declare a state of emergency to get aid from international organizations.[45] The Famine Early Warning Systems Network reported that the rainy season of 2018/2019 not only started a month later than normal but also recorded below-average amounts of rain.[47] Data from the Climate Hazards Group InfraRed Precipitation Station (CHIRP) shows rainfall in Lesotho between October 2018 and February 2019 ranged from 55% to 80% below normal rates.[47] In March 2019, the Lesotho Vulnerability Assessment and Analysis Committee conducted a report that initially predicted that 487,857 people in the country need humanitarian assistance because of the effects of drought.[47] There are a variety of different ways drought in Lesotho has led to the need for humanitarian assistance. Some hygiene practices that result from "a lack of clean water" can cause cases of typhoid and diarrhea. Lack of available water indirectly leads to an "increased risk" for women and girls who collect water for household consumption as they must spend more time and travel longer distances while running the risk of being physically or sexually assaulted.[47] Drought in Lesotho leads to both migration to more urban areas and immigration to South Africa for new opportunities and to escape food insecurity.[46] The report found that between July 2019 and June 2020 640,000 people in Lesotho are expected to be affected by food insecurity as a result of "unproductive harvests as well as the corresponding rise in food prices because of the drought".[47] Wildlife There are known to be 339 bird species in Lesotho, including 10 globally threatened species and two introduced species, 17 reptile species, including geckos, snakes and lizards, and 60 mammal species endemic to Lesotho, including the endangered white-tailed rat. Lesotho's flora is alpine, due to mountainous terrain. The Katse Botanical Gardens houses a collection of medicinal plants and has a seed bank of plants from the Malibamat'so River area.[48][49] Three terrestrial ecoregions lie within Lesotho's boundaries: Drakensberg alti-montane grasslands and woodlands, Drakensberg montane grasslands, and Highveld grasslands.[50] Economy The economy of Lesotho is based on agriculture, livestock, manufacturing and mining, and depends on inflows of workers' remittances and receipts from the Southern African Customs Union (SACU).[51][52] The majority of households subsist on farming. The formal sector employment consists mainly of female workers in the apparel sector, male migrant labour, primarily miners in South Africa for 3 to 9 months, and employment by the Government of Lesotho (GOL). The western lowlands form the main agricultural zone. Almost 50% of the population earn income through informal crop cultivation or animal husbandry with nearly two-thirds of the country's income coming from the agricultural sector. The percentage of the population living below USD Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) US$1.25/day fell from 48% to 44% between 1995 and 2003.[51] Lesotho has taken advantage of the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) to become the largest exporter of garments to the US from sub-Saharan Africa.[53] US brands and retailers sourcing from Lesotho include Foot Locker, Gap, Gloria Vanderbilt, JCPenney, Levi Strauss, Lululemon Athletica, Saks, Sears, Timberland and Wal-Mart.[54] In mid-2004, its employment reached over 50,000, mostly female, marking the first time that manufacturing sector workers outnumbered government employees. In 2008 it exported goods worth 487 million dollars mainly to the US. Since 2004, employment in the sector has dwindled to about 45,000 in mid-2011 due to international competition in the garment sector. It was the largest formal sector employer in Lesotho in 2011.[55] In 2007, the average earnings of an employee in the textile sector were US$103 per month, and the official minimum wage for a general textile worker was US$93 per month. The average gross national income per capita in 2008 was US$83 per month.[55] The sector initiated a program to fight HIV/AIDS called Apparel Lesotho Alliance to Fight AIDS (ALAFA). It is an industry-wide program providing disease prevention and treatment for workers.[56] Water and diamonds are some of Lesotho's natural resources.[51] Water is used through the 21-year, multibillion-dollar Lesotho Highlands Water Project (LHWP), under the authority of the Lesotho Highlands Development Authority. The project commenced in 1986.[57] LHWP is designed to capture, store, and transfer water from the Orange River system to South Africa's Free State and greater Johannesburg area. Completion of the first phase of the project has made Lesotho "almost completely self-sufficient" in the production of electricity and generated approximately US$70 million in 2010 from the sale of electricity and water to South Africa.[58] Diamonds are produced at the Letšeng, Mothae, Liqhobong, and Kao mines, which combined are estimated to produce 240,000 carats of diamonds in 2014, worth US$300 million. The Letšeng mine is estimated to produce diamonds with an average value of US$2172 per carat, making it the world's richest mine on an average price per carat basis.[59] The sector underwent a setback in 2008 as the result of the world recession and rebounded in 2010 and 2011. The export of diamonds reached US$230 million in 2010–2011.[60] In 1957, a South African adventurer, colonel Jack Scott, accompanied by Keith Whitelock, set out prospecting for diamonds. They found their diamond mine at 3,100 m elevation, on top of the Maluti Mountains in northeastern Lesotho, some 70 km from Mokhotlong at Letšeng. In 1967, a 601-carat (120.2 g) diamond (Lesotho Brown) was discovered in the mountains by a Mosotho woman. In August 2006, a 603-carat (120.6 g) white diamond, the Lesotho Promise, was discovered at the Letšeng-la-Terae mine. Another 478-carat (95.6 g) diamond was discovered at the same location in 2008.[61] Lesotho has progressed in moving from a predominantly subsistence-oriented economy to a lower middle-income economy through exporting natural resources and manufacturing goods. The exporting sectors have brought "higher and more secure" incomes to a portion of the population.[51] The global economic crisis caused Lesotho to suffer a loss of textile exports and jobs due to the economic slowdown in the United States, one of their export destinations. Reduced diamond mining and exports, including a drop in the price of diamonds and a drop in SACU revenues due to the economic slowdown in the South African economy contributed to the crisis. A reduction in worker remittances due to the "weakening" of the South African economy, contraction of the mining sector, and related job losses in South Africa contributed to Lesotho's GDP growth slowing to 0.9% in 2009.[51] The official currency is the loti (plural: maloti) which can be used interchangeably with the South African rand. The loti is at par with the rand. Lesotho, Eswatini, Namibia, and South Africa form a common currency and exchange control area known as the Common Monetary Area (CMA). 100 lisente (singular: sente) equal 1 loti. Demographics

Lesotho has a population of approximately 2,281,454.[63][64] The population distribution of Lesotho is 25% urban and 75% rural. It is estimated that the annual increase in urban population is 3.5%.[65] 60.2% of the population is between 15 and 64 years of age.[65] Ethnic groups and languagesLesotho's ethno-linguistic structure consists mostly of the Basotho, a Bantu-speaking people: an estimated 99.7% of the people identify as Basotho. In this regard, Lesotho is part of a minority of African countries that are nation states with a single dominant cultural ethnic group and language; the majority of African nations' borders were drawn by colonial powers and do not correspond to ethnic boundaries or pre-colonial polities.[66] Basotho subgroups include the Bafokeng, Batloung, Baphuthi, Bakuena, Bataung, Batšoeneng, and Matebele. About 1% of the population consists of Europeans, Asians, and Xhosa.[67] Religion In December 2011, the population of Lesotho is estimated to be more than 95% Christian.[68] Among these estimations, Catholics represent 49.4% of the population,[69] served by the province of the Metropolitan Archbishop of Maseru and his three suffragans (the bishops of Leribe, Mohale's Hoek and Qacha's Nek), who form the national episcopal conference. Protestants account for 18.2% of the population, Pentecostals 15.4%, Anglicans 5.3%, and other Christians an additional 1.8%.[69] Non-Christian religions represent 9.6% of the population, and those of no religion 0.2%.[69] Education and literacy According to estimates, 85% of women and 68% of men over the age of 15 are literate.[70] As such, Lesotho holds "one of the highest literacy rates in Africa",[65] in part because Lesotho invests over 12% of its GDP in education.[71] Female literacy (84.93%) exceeds male literacy (67.75%) by 17.18%. According to a study by the Southern and Eastern Africa Consortium for Monitoring Educational Quality in 2000, 37% of grade 6 pupils in Lesotho (average age 14 years) are at or above reading level 4, "Reading for Meaning."[72] A pupil at this level of literacy can read ahead or backwards through parts of text to link and interpret information. While education is not compulsory, the Government of Lesotho is incrementally implementing a program for free primary education.[73] In a 2009 report, adult literacy is as high as 82%. Among the children below the age of 5 years, 20% are underweight.[74] According to the International Telecommunication Union, 3.4% of the population use the internet. A service from Econet Telecom Lesotho expanded the country's access to email through entry-level, low-end mobile phones and consequently improved access to educational information. The African Library Project works to establish school and village libraries in partnership with US Peace Corps Lesotho[75] and the Butha-Buthe District of Education. HealthThe country is among the "Low Human Development" countries (rank 160 of 187 on the Human Development Index as classified by UNDP), with 52 years of life expectancy for men and women, estimated in 2009.[76][77] Life expectancy at birth in Lesotho in 2016 was 51 years for men and 55 for women. Infant mortality is about 8.3%. As of 2018, Lesotho's adult H.I.V./A.I.D.S. prevalence rate of 23.6% was the second-highest in the world, after Eswatini.[78] In 2021, Lesotho had a 22.8% H.I.V. prevalence rate among people between 15 and 49 years of age.[79] The country has the highest incidence of tuberculosis in the world.[80] According to the 2006 census of Lesotho, around 4% of the population is thought to have some sort of disability. There are concerns regarding the reliability of the methodologies used and the real figure is thought to be closer to the global estimate of 15%. According to a survey conducted by the Lesotho National Federation of Organisations of the Disabled in conjunction with SINTEF,[81] people with disability in Lesotho face social and cultural barriers which prevent them from accessing education, health-care and employment on an equal basis with others. On 2 December 2008, Lesotho became the 42nd country in the world to sign the U.N. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. According to World Health Organization data, Lesotho has had the world's highest rate of suicide per capita since 2008.[82] Violence against women in LesothoAccording to the U.N., Lesotho has the highest rape rate of any country (91.6 per 100,000 people reported rape in 2008).[83] International data from UNODC found the incidence of rape recorded in 2008 by the police to be the highest in Lesotho out of any country in the study.[84] A study in Lesotho found that 61% of women reported having experienced sexual violence at some point in their lives, of whom 22% reported being physically forced to have sexual intercourse.[85] In the 2009 D.H.S. survey, 15.7% of men said that a husband is justified in hitting or beating his wife if she refuses to have sex with him, while 16% said a husband is justified in using force to have sex.[86] In another study, researchers concluded that "Given the high prevalence of HIV in Lesotho, programs should address women's right to control their sexuality."[87] The Married Persons Equality Act 2006 gives equal rights to wives regarding their husbands, abolishing the husband's marital power.[88] The World Economic Forum's 2020 Gender Gap Report ranks Lesotho 88th worldwide for gender parity, while neighboring South Africa ranks 17th.[89] Culture The cuisine of Lesotho includes African traditions and British influences.[90] The national dish of Lesotho is Motoho, a fermented sorghum porridge. Some staple foods include pap, or 'mealies', a cornmeal porridge covered with a sauce consisting of vegetables. Tea and locally brewed beer are choices for beverages. Lesotho is famed for its fermented ginger beer, of which there are two types with and without raisins. Sishenyama is regularly sold independently throughout Lesotho with side-dishes such as cabbage, pap and baked bean salad.[91] The national dress revolves around the Basotho blanket, a covering made originally of wool. Most of the Basotho blanket is now made out of acrylic fibres. The main manufacturer of the Basotho blanket is Aranda, which has a factory over the border in South Africa. British influence in Lesotho is visible through the remnants of trading posts that were operated from the 18th century into the 20th century.[92] These are in the villages of Roma, Ramabantana, Ha Matala, Malealea and Semonkong. In the past, these lodges were employed in the sale of fuel, grains, mealie meals and animals. Examples of San rock art can be found in the mountains throughout Basutoland. There are examples in the village of Ha Matela.[93] The Morija Arts & Cultural Festival is held annually in the town of Morija where missionaries arrived in 1833. Basotho ponyThe Basotho pony was historically ridden into battle and in the modern day used for transport and agriculture.[citation needed] Film and mediaRyan Coogler, director of the 2018 film Black Panther, stated that his depiction of Wakanda was inspired by Lesotho.[94][95] Basotho blankets "became more known" as a result of the film.[96] In November 2020, the film This Is Not a Burial, It's a Resurrection became the first Lesotho film to be submitted for the Academy Award for Best International Feature Film by the country.[97] See alsoReferences

External links

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||