|

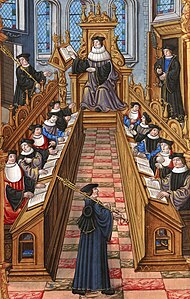

Academic degreeAn academic degree is a qualification awarded to a student upon successful completion of a course of study in higher education, usually at a college or university. These institutions often offer degrees at various levels, usually divided into undergraduate and postgraduate degrees. The most common undergraduate degree is the bachelor's degree, although some educational systems offer lower-level undergraduate degrees such as associate and foundation degrees. Common postgraduate degrees include engineer's degrees, master's degrees and doctorates. In the UK and countries whose educational systems are based on the British system, honours degrees are divided into classes: first, second (broken into upper second, or 2.1, and lower second, or 2.2) and third class. History Emergence of the doctor's and master's degrees and the licentiateThe doctorate (Latin: doceo, "I teach") first appeared in medieval Europe as a license to teach (Latin: licentia docendi) at a medieval university.[1] Its roots can be traced to the early church when the term "doctor" referred to the Apostles, church fathers and other Christian authorities who taught and interpreted the Bible.[1] The right to grant a licentia docendi was originally reserved by the church which required the applicant to pass a test, take an oath of allegiance, and pay a fee. The Third Council of the Lateran of 1179 guaranteed the access – now largely free of charge – of all able applicants, who were, however, still tested for aptitude by the ecclesiastic scholastic.[2] This right remained a point of contention between the church authorities and the slowly emancipating universities, but was granted by the Pope to the University of Paris in 1231 where it became a universal license to teach (licentia ubique docendi).[2] While the licentia continued to hold a higher prestige than the bachelor's degree (Baccalaureus), it was ultimately reduced to an intermediate step to the Magister and doctorate, both of which now became the exclusive qualification for teaching.[2] In universities, doctoral training was a form of apprenticeship to a guild.[3] The traditional term of study before new teachers were admitted to the guild of "Master of Arts" was seven years. This was the same as the term of apprenticeship for other occupations. Originally the terms "master" and "doctor" were synonymous,[4] but over time the doctorate came to be regarded as a higher qualification than the master's degree.[citation needed] Today the terms "master" (from the Latin magister, lit. 'teacher'), "Doctor", and "Professor" signify different levels of academic achievement, but in the Medieval university, they were equivalent terms. The use of them in the degree name was a matter of custom at a university. Most universities conferred the Master of Arts, although the highest degree was often termed Master of Theology/Divinity or Doctor of Theology/Divinity, depending on the place.[citation needed] The earliest doctoral degrees (theology – Divinitatis Doctor (D.D.), law – Legum Doctor (LL.D., later D.C.L.) and medicine – Medicinæ Doctor (M.D., D.M.)) reflected the historical separation of all higher University study into these three fields. Over time, the D.D. has gradually become less common outside theology and is now mostly used for honorary degrees, with the title "Doctor of Theology" being used more often for earned degrees. Studies outside theology, law, and medicine were then called "philosophy", due to the Renaissance conviction that real knowledge could be derived from empirical observation. The degree title of Doctor of Philosophy is a much later creation and was not introduced in England before 1900. Studies in what once was called philosophy are now classified as sciences and humanities.[citation needed] George Makdisi theorizes that the ijazah issued in medieval Islamic madrasas in the 9th century was the origin of the doctorate that later appeared in medieval European universities.[5] Alfred Guillaume,[6] Syed Farid al-Attas[6] and Devin J. Stewart agree that there is a resemblance between the ijazah and the university degree.[7] However, Toby Huff and others reject Makdisi's theory.[8][9][10][11] Devin J. Stewart finds that the ijazat al-ifta, license to teach Islamic law and issue legal opinions, is most similar to the medieval European university degree in that it permits entry into certain professions. A key difference was that the granting authority of the ijaza was an individual professor whereas the university degree was granted by a corporate entity.[12] The University of Bologna in Italy, regarded as the oldest university in Europe, was the first institution to confer the degree of Doctor in Civil Law in the late 12th century; it also conferred similar degrees in other subjects, including medicine.[13] The University of Paris used the term "master" for its graduates, a practice adopted by the English universities of Oxford and Cambridge, as well as the ancient Scottish universities of St Andrews, Glasgow, Aberdeen and Edinburgh. Emergence of the bachelor's degreeIn medieval European universities, candidates who had completed three or four years of study in the prescribed texts of the trivium (grammar, rhetoric and logic) and the quadrivium (arithmetic, geometry, astronomy and music), together known as the Liberal Arts, and who had successfully passed examinations held by their master, would be admitted to the degree of Bachelor of Arts. The term "bachelor" comes from the Latin baccalaureus, a term previously used to describe a squire (i.e., apprentice) to a knight. Further study and, in particular, successful participation in, and moderation of, disputations would earn one the Master of Arts degree, from the Latin magister, "master" (typically indicating a teacher), entitling one to teach these subjects. Masters of Arts were eligible to enter study under the "higher faculties" of Law, Medicine or Theology and earn first a bachelor's and then master's or doctor's degree in these subjects. Thus, a degree was only a step on the way to becoming a fully qualified master – hence the English word "graduate", which is based on the Latin gradus ("step"). Evolution of the terminology of degreesThe naming of degrees eventually became linked to the subjects studied. Scholars in the faculties of arts or grammar became known as "masters", but those in theology, medicine and law were known as "doctors". As a study in the arts or grammar was a necessary prerequisite to study in subjects such as theology, medicine and law, the degree of doctor assumed a higher status than the master's degree. This led to the modern hierarchy in which the Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.), which in its present form as a degree based on research and dissertation is a development from 18th- and 19th-century German universities, is a more advanced degree than the Master of Arts (M.A.). The practice of using the term doctor for PhDs developed within German universities and spread across the academic world. The French terminology is tied closely to the original meanings of the terms. The baccalauréat (cf. "bachelor") is conferred upon French students who have completed their secondary education and allows the student to attend university. When students graduate from university, they are awarded a licence, much as the medieval teaching guilds would have done, and they are qualified to teach in secondary schools or proceed to higher-level studies. Spain had a similar structure: the term "Bachiller" was used for those who finished the secondary or high-school level education, known as "Bachillerato". The standard Spanish university 5-year degree was "Licenciado", (although there were a few 3-year associate degrees called "diplomaturas", from where the "diplomados" could move to study a related licenciatura). The highest level was "Doctor". Degrees awarded by institutions other than universitiesIn the past, degrees have been directly issued by the authority of the monarch or by a bishop, rather than any educational institution. This practice has mostly died out. In Great Britain, Lambeth degrees are still awarded by the Archbishop of Canterbury.[14] The Archbishop of Canterbury's right to grant degrees is derived from the Peter's Pence Act 1533, which empowered the Archbishop to grant dispensations previously granted by the Pope.[15] Among educational institutions, St David's College, Lampeter, was granted limited degree awarding powers by royal charter in the nineteenth century, despite not being a university. The University College of North Staffordshire was also granted degree awarding powers on its foundation in 1949, despite not becoming a university (as the University of Keele) until 1962. Following the Education Reform Act 1988, many educational institutions other than universities have been granted degree-awarding powers, including higher education colleges and colleges of the University of London, many of which are now effectively universities in their own right.[16] Academic dressIn many countries, gaining an academic degree entitles the holder to assume distinctive academic dress particular to the awarding institution, identifying the status of the individual wearing them. Laws on granting and use of degreesIn many countries, degrees may only be awarded by institutions authorised to do so by the national or regional government. Frequently, governments will also regulate the use of the word university in the names of businesses. This approach is followed, for example, by Australia,[17] the United Kingdom[18] and Israel.[19] The use of fake degrees by individuals, either obtained from a bogus institution or simply invented, is often covered by fraud laws.[20][21] Indicating earned degreesDepending on the culture and the degree earned, degrees may be indicated by a pre-nominal title, post-nominal letters, a choice of either, or not indicated at all. In countries influenced by the UK, post-nominal letters are the norm, with only doctorates granting a title, while titles are the norm in many northern European countries. Depending on the culture and the purpose of the listing, only the highest degree, a selection of degrees, or all degrees might be listed. The awarding institution may be shown and it might be specified if a degree was at honours level, particularly where the honours degree is a separate qualification from the ordinary bachelor's degree.[22] For member institutions of the Association of Commonwealth Universities, there is a standard list of abbreviations for university names given in the Commonwealth Universities Yearbook. In practice, many variations are used and the Yearbook notes that the abbreviations used may not match those used by the universities concerned.[23] For some British universities it is traditional to use Latin abbreviations, notably 'Oxon' and 'Cantab' for the universities of Oxford and Cambridge respectively,[24][25] in spite of these having been superseded by English 'Oxf' and 'Camb' in official university usage,[26] particularly in order to distinguish the Oxbridge MA from an earned MA.[27] Other Latin abbreviations commonly used include 'Cantuar' for Lambeth degrees (awarded by the Archbishop of Canterbury),[26] 'Dunelm' for Durham University,[28][29] 'Ebor' for the University of York[30] and 'Exon' for the University of Exeter.[31] The Ancient universities of Scotland and the University of London have abbreviations that are the same in English and Latin. (See Universities in the United Kingdom § Post-nominal abbreviations for a more complete list and discussion of abbreviations for British universities.) Confusion can result from universities sharing similar names, e.g. the University of York in the UK and York University in Canada or Newcastle University in the UK and the University of Newcastle in Australia. In this case, the convention is to include a country abbreviation with the university's name. For example, 'York (Can.)' and 'York (UK)' or 'Newc (UK)' and 'Newc (Aus.) are commonly used to denote degrees conferred by these universities where the potential for confusion exists,[32] and institution names are given in this form in the Commonwealth Universities Yearbook.[23] Abbreviations used for degrees vary between countries and institutions, e.g. MS indicates Master of Science in the US and places following American usage, but Master of Surgery in the UK and most Commonwealth countries, where the standard abbreviation for Master of Science is MSc. Common abbreviations include BA and MA for Bachelor and Master of Arts, BS/BSc and MS/MSc for Bachelor and Master of Science, MD for Doctor of Medicine and PhD for Doctor of Philosophy.[33][34] Online degreeAn online degree is an academic degree (usually a college degree, but sometimes the term includes high school diplomas and non-degree certificate programs) that can be earned primarily or entirely on a distance learning basis through the use of an Internet-connected computer, rather than attending college in a traditional campus setting. Improvements in technology, the increasing use of the Internet worldwide, and the need for people to have flexible school schedules that enable them to work while attending school have led to a proliferation of online colleges that award associate's, bachelor's, master's, and doctoral degrees.[35] Degree systems by regions

AsiaBangladesh, India and PakistanBangladesh and India mostly follow the colonial era British system for the classification of degrees,[36] however, Pakistan has recently switched[when?] to the US model of a two-year associate degree and a four-year bachelor's degree program. The arts, referring to the performing arts and literature, may confer a Bachelor of Arts (BA) and a Master of Arts (MA). Management degrees are also classified under 'arts' but are nowadays considered a separate stream, with degrees of Bachelor of Business Administration (BBA) and Master of Business Administration (MBA). Science refers to the basic sciences and natural science (Biology, Physics, Chemistry, etc.); the corresponding degrees are Bachelor of Science (BSc) and Master of Science (MSc). Information Technology degrees are conferred specially in the field of computer science, and include Bachelor of Science in Information Technology (B.Sc.IT.) and Master of Science in Information Technology (M.Sc.IT.). The engineering degree in India follows two nomenclatures, Bachelor of Engineering (B.Eng.) and Bachelor of Technology (B.Tech.). Both represent bachelor's degree in engineering.[37] In Pakistan, engineering degrees are Bachelor of Engineering (B.E.) and Bachelor of Science in Engineering (B.S./B.Sc. Engineering). Both are the same in curriculum, duration and pattern, and differ only in nomenclature. The engineering degree in Bangladesh is a Bachelor of Science in Engineering (B.Sc. Engineering). Other degrees include the medical degree (Bachelor of Medicine & Bachelor of Surgery (MBBS)), dental degree (Bachelor of Dental Surgery (BDS)) and computer application degrees (Bachelor of Computer Application (BCA)) and Master of Computer Application (MCA). IndonesiaIndonesia follows the colonial Dutch system for the classification of degrees. However, Indonesia has been dropping the Dutch titles and developing its own distinctions. Sri LankaSri Lanka, like many other commonwealth countries, follows the British system, but with its own distinctions. Degrees are approved by the University Grants Commission.[38] AfricaTunisiaTunisia's educational grading system, ranging from elementary school to Ph.D. programs, operates on a scale of 0 to 20. The minimum score for passing is set at 10 out of 20. This numerical system exclusively evaluates a student's academic accomplishments, serving as the determinant for admission into advanced programs. For instance, a student's grades obtained for their bachelor's degree are considered when they apply for a Master's program. Level 4 courses, which include the first year of a Bachelor's program or a Higher National Certificate (HNC), may allow students to enter directly into the second year of a Bachelor's program, provided that the course they completed is the same as the one they are applying for. South AfricaIn South Africa, grades (also known as "marks") are presented as a percentage, with anything below 50% considered a failure. Students who receive a failing grade may have the opportunity to rewrite the exam, depending on the criteria established by their institution. Degrees in almost any field of study can be pursued at one of the institutions in the country, with certain institutions being known for excelling in specific fields. Major fields of study across the country include Arts, Commerce, Engineering, Law, Medicine, Science, and Theology. The South African Qualifications Authority (SAQA)[39] has developed a credit-based system for degrees, with different levels of National Qualifications Framework (NQF) ratings corresponding to each degree level. For example, an undergraduate degree in Science is rated at NQF level 6, while an additional year of study in that discipline would result in an NQF level 8 (honours degree) rating. KenyaIn Kenya, the first undergraduate degree is pursued after students have completed four years of secondary school education and attained at least a C+ (55–59%) on the Kenya Certificate of Secondary Education (KCSE). Students pursuing a degree in engineering, such as B.Sc. Mechanical Engineering or B.Sc. Electrical and Electronics Engineering, are required to join programs that are accredited by the Engineers Board of Kenya and the Commission for University Education. The B.Sc. degree in engineering typically takes five years to complete. A degree in medicine or surgery may take six to seven years, while a degree in education or management takes around four years. For students pursuing a master's degree, they must have completed an undergraduate degree and attained at least a second-class honours upper division (60–69%) or lower division plus at least two years of relevant experience. Most master's degree programs take two years to complete. In an engineering master's degree program, students are typically required to publish at least one scientific paper in a peer-reviewed journal. To pursue a doctor of philosophy degree, students must have completed a relevant master's degree. They are required to carry out a supervised scientific study for a minimum of three years and publish at least two scientific first-author papers in peer-reviewed journals relevant to their area of study. Currently, Kenya is implementing a Competency Based Curriculum (CBC) that follows a 2–6–3–3 education system to replace the existing 8–4–4 system which allows confirmation of undergraduate degrees upon successful completion. The CBC system was introduced in 2017.[40][41] EuropeSince the Convention on the Recognition of Qualifications concerning Higher Education in the European Region in 1997 and the Bologna Declaration in 1999, higher education systems in Europe have been undergoing harmonisation through the Bologna Process, which is based on a three-cycle hierarchy of degrees: Bachelor's/Licence – Master's – Doctorate. This system is gradually replacing the two-stage system previously used in some countries and is combined with other elements such as the European Credit Transfer and Accumulation System (ECTS) and the use of Diploma Supplements to make comparisons between qualifications easier. The European Higher Education Area (EHEA) was formally established in 2010 and, as of September 2016, has 50 members.[42] The implementation of the various elements of the EHEA varies between countries. Twenty-four countries have fully implemented a national qualifications framework, and a further ten have a framework but have not yet certified it against the overarching framework. In 38 countries, ECTS credits are used for all higher education programmes, and 31 countries have fully implemented diploma supplements. Only 11 countries have included all the major points of the Lisbon Recognition Convention in national legislation.[43] Since 2008, the European Union has been developing the European Qualifications Framework (EQF). This is an eight-level framework designed to allow cross-referencing of the various national qualifications frameworks. While it is not specific to higher education, the top four levels (5–8) correspond to the short cycle, first cycle, second cycle, and third cycle of the EHEA.[44][45] AustriaIn Austria, there are currently two parallel systems of academic degrees:

The two-cycle degree system was phased out by 2010, with a few exceptions. However, some of the established degree naming has been preserved, allowing universities to award the "Diplom-Ingenieur" (and for a while also the "Magister") to graduates of the new-style Master programmes.[46] BelgiumWhile higher education is regulated by the three communities of Belgium, all have common and comparable systems of degrees that were adapted to the Bologna structure during the 2000s. The primary 3-cycle structure is called BMD (Bachelor-Master-Doctorate; French: Bachelier-Master-Doctorat or Dutch: Bachelor-Master-Doctoraat). In the first cycle, the Bachelor's degree is issued after 180 ECTS (3 years, EQF level 6). Other first cycle degrees include the one-year Advanced Bachelor's degree degree (French: Bachelier de spécialisation, lit. 'Specialized Bachelor'; Dutch: Bachelor-na-bachelor, lit. 'Bachelor-after-bachelor') and the Brevet (in the French-speaking Community only) for short-cycle higher education programmes. Bachelor's degrees are followed in the second cycle (EQF level 7) by Master's degrees that last two years, completing an extra 120 ECTS credits. The master's degree can be followed by an Advanced Master's degree (French: Master de spécialisation, lit. 'Specialized Master'; Dutch: Master-na-master, lit. 'Master-after-master') that lasts one year (60 ECTS). The third cycle of Belgium's higher education is covered by the Doctorate degree (French: Doctorat; Dutch: Doctoraat) that covers a 3-to-7-year-long PhD, depending on whether the doctoral student has teaching responsibilities in addition to conducting research or not (typically 6 years for teaching assistants and 4 years for research-only mandates). Czech RepublicThe Czech Republic has implemented the Bologna process, and functionally has three degrees: Bachelor (3 years), Master (2 years after Bachelor) and Doctor (4 years after Master). The Czech Republic also has voluntary academic titles called "small doctorates" (e.g. RNDr. for natural sciences, PhDr. for philosophy, JUDr. for law etc.) which are achieved after passing an additional exam. Medical students do not get bachelor's or master's degrees, but instead attend a six year program and obligatory exam they achieve the title MUDr. (equivalent to MD degree in the United States of America)[clarification needed], or MDDr. for dentists and MVDr. for veterinary physicians. They can also get a "big doctorate" (Ph.D.) after another three or four years of study. Bachelor's degrees, master's degrees and small doctorates in the form of letters (Bc., Mgr., Ing., ...) are listed before the person's name, and Doctor's degrees (Ph.D.) are listed after name (e.g. MUDr. Jan Novák, Ph.D.). The Czech Republic previously had more degrees that were awarded.[citation needed] DenmarkBefore the adoption of the Bologna Process, the lowest degree that would normally be studied at universities in Denmark was equivalent to a master's degree (kandidatgrad). Officially, a bachelor's degree was always obtained after 3 years' university studies. Various medium-length (2–4 years) professional degrees have been adopted, so they now have status as professional bachelor's degrees of varying length. As opposed to academic bachelor's degrees, they are considered to be "applied" degrees. A professional bachelor's degree is 180, 210, or 240 ECTS-points.[47] The academic degrees available at universities are:[47]

FinlandHistorically, the Finnish higher education system is derived from the German system. The current system of higher education comprises two types of higher education institutions, the universities and the polytechnics, many of whom refer to themselves as universities of applied sciences (UAS).[48][49] With the exception of a few fields, such as medicine and dentistry, the Finnish system of higher education degrees is in compliance with the Bologna process. Universities award bachelor's degrees (kandidaatti / kandidat), Master's degrees (maisteri / magister) and doctoral degrees (lisensiaatin tutkinto / licentiat examen and tohtorin tutkinto / doktorexamen). In most fields, the system of doctoral degrees is two-tier, the degree of licentiate is an independent academic degree but completing the degree of doctor does not require completion of a licentiate degree. The polytechnics (universities of applied sciences) have the right to award bachelor's and master's degrees; the degree titles are distinct from the titles used for university degrees. In general, students who are admitted to bachelor studies at a university have the right to continue to studies at master level. At polytechnics, the right to continue to master-level studies has to be applied for separately and there is also a work experience requirement. The majority of master's degree holders have graduated from university. The degrees awarded by the universities and polytechnics are at par by law, but the content and orientation of studies is different. A master's degree obtained at a polytechnic gives the same academic right to continue studies at doctoral level as a master's degree obtained at a university. France

The French national education system makes a distinction between a diplôme national ("national degree") and diplôme universitaire ("university degree"). The former, which are considered to have a higher status, are controlled by the state and issued by universities on behalf of the responsible ministry; the latter are controlled and granted by the universities themselves.[67] Additionally, private universities and schools may be recognised by the state with a diplôme visé ("recognised degree") and then, after five years of recognition, have their degrees validated by the state, the validation having to be renewed every six years.[68] Historically, academic degrees were orientated towards research, and the vocational education system awarded only diplomas. Since the implementation of the Bologna Process in France, the degree-granting system is being simplified: schools continue to grant their own diplomas, but the state's recognition in degree awarding is more important than before. Diploma courses such as the university Bachelor of Technical Studies (bachelor universitaire de technologie; BUT) are recognised as vocational bachelor's degree qualifications worth 180 ECTS credits; the Advanced Technician Certificate (brevet de technician supérieur; BTS) is now recognised as a "short cycle" qualification worth 120 ECTS credits, allowing progression from these to academic qualifications.[69] However, in France there are diplomas that are not recognised as degrees, such as specific diplomas designed by colleges (écoles supérieures), like the mastère spécialisé (accredited by the Conférence des Grandes Écoles but not automatically by the French Government). Since 2002, grande école diplomas have been able to award a university degree, such as the Sciences Po Bachelor, which is a state-accredited diploma that awards a bachelor's degree (Licence in French). The recognised degrees are in three levels, following the Qualifications Framework of the European Higher Education Area. These are the licence (first level), master (second level) and doctorat (third level). All licence degrees take 3 years (180 ECTS credits) and all master's degrees take 2 years (120 ECTS credits). There are also 5-year (300 ECTS credits) engineer's degrees, which are master's degrees. In addition to the doctorate, which is always a research degree, the Diplôme d'Etat de docteur en médicine and the Diplôme d'Etat de docteur vétérinaire are third level qualifications and recognized as level 7 in EQF.[70] GermanyTraditionally in Germany, students graduated after four-to-six years either with a Magister degree in social sciences, humanities, linguistics or the arts, or with a Diplom degree in the natural sciences, economics, business administration, political science, sociology, theology or engineering. Those degrees were the first, and at the same time highest, non-PhD/Doctorate-titles in many disciplines before their gradual replacement by other Anglo-Saxon-inspired master's and bachelor's degrees under the Bologna process. The Magister and Diplom awarded by universities, both of which require a final thesis, are considered equivalent to a master's degree, although the Diplom awarded by a Fachhochschule (university of applied sciences) is at bachelor's degree level.[71] A special kind of examination is the Staatsexamen (State Examination). It is not an academic degree but a government licensing examination that future doctors, dentists, teachers, lawyers (solicitors), judges, public prosecutors, patent attorneys and pharmacists have to pass in order to be eligible to work in their profession. Students usually study at university for three to six years, depending on the field, before they take the first Staatsexamen. While this is normally at the master's level, a few courses (e.g. primary and lower secondary level teaching), which have a standard study period of three years, are assigned to the bachelor's level.[72] After the first Staatsexamen, teachers and lawyers go through a form of pupillage, the Vorbereitungsdienst, for two years, before they are able to take the second Staatsexamen, which tests their practical abilities in their jobs.[71] At some institutions pharmacists and jurists can choose whether to be awarded the first Staatsexamen or a master's degree (or formerly the Diplom). Since 1999, the traditional degrees have been replaced by bachelor's (Bachelor) and master's (Master) degrees as part of the Bologna process. The main reasons for this change are to make degrees internationally comparable and to introduce degrees to the German system that take less time to complete (German students typically took five years or more to earn a Magister or Diplom). Some universities were initially resistant to this change, considering it a displacement of a venerable tradition for the pure sake of globalization. However, universities had to fulfill the new standard by the end of 2007. Enrollment into Diplom and Magister programs is no longer possible at most universities, with a few exceptions. Programs leading to Staatsexamen did not usually make the transition to Bologna degrees. Doctorates are issued with various designations, depending on the faculty: e.g., Doktor der Naturwissenschaften (Doctor of Natural Science); Doktor der Rechtswissenschaften (Doctor of Law); Doktor der Medizin (Doctor of Medicine); Doktor der Philosophie (Doctor of Philosophy), to name just a few. Multiple doctorates and honorary doctorates are often listed, and even used in forms of address, in German-speaking countries. A Diplom, Magister, Master's or Staatsexamen student can proceed to a doctorate. Well-qualified bachelor's graduates can also enrol directly into PhD programs after a procedure to determine their aptitude is administered by the admitting university.[73] The doctoral degree—such as Dr. rer. nat., Dr. phil. and others—is the highest academic degree in Germany and is generally a research degree. The degree Dr. med. for medical doctors has to be viewed differently; medical students usually write their doctoral theses right after they have completed studies, without any previously conducted scientific research, just as students in other disciplines write a Diplom, Magister or Master's thesis.[citation needed] Higher doctorates, such as the D.Sc. degree in the UK, are not present in the German system. However, sometimes incorrectly regarded as a degree, the Habilitation is a higher academic qualification—in Germany, Austria, Switzerland and the Czech Republic—that grants a further teaching and research endorsement after a doctorate. It is earned by writing a second thesis (the Habilitationsschrift) or presenting a portfolio of first-author publications on an advanced topic. The exact requirements for satisfying a Habilitation depend on individual universities. The "habil.", as it is abbreviated, to indicate that a habilitation has been awarded after the doctorate, was traditionally the conventional qualification for serving at least as a Privatdozent (e.g. "PD Dr. habil.") (senior lecturer) in an academic professorship. Some German universities no longer require the Habilitation, although preference may still be given to applicants who have this credential in securing academic posts in the more traditional fields. GreeceIn Greece access to university is possible after national exams (Panhellenic Exams). The Greek academic degrees are:

IrelandIreland operates under a National Framework of Qualifications (NFQ). The school-leaving qualification attained by students is called the Leaving Certificate. It is considered as Level 4–5 in the framework. This qualification is the traditional route of entry into third-level education. There are also Level 5 qualifications in certain vocational subjects (e.g. Level 5 Certificate in Restaurant Operations) awarded by the Further Education and Training Awards Council (FETAC). Advanced Certificates at Level 6 are also awarded by FETAC. The Higher Education and Training Awards Council (HETAC) awards the following: A higher certificate at Level 6; An ordinary bachelor's degree at Level 7; An honours bachelor's degree or higher diploma at Level 8; A master's degree or postgraduate diploma at Level 9; A doctoral degree or higher doctorate at Level 10.[74] These are completed in institutes of technology or universities. ItalyIn Italy access to university is possible after gaining the Diploma di Maturità at 19 years of age, following 5 years of study in a specific high school focused on certain subjects (e.g. liceo classico focused on classical subjects, including philosophy, ancient Greek and Latin; liceo scientifico focused on scientific subjects such as maths, chemistry, biology and physics but also including philosophy, ancient Latin and Italian literature; liceo linguistico focused on foreign languages and literature; istituto tecnico focused on practical and theoretical subjects such as mechanics, aerospace, shipbuilding, electronics, computer science, telecommunications, chemistry, biology, fashion industry, food industry, building technology, law and economics). After gaining the diploma one can enter university and enrol in any curriculum (e.g. physics, medicine, chemistry, engineering, architecture): all high school diplomas allow access to any university curriculum, although most universities have pre-admission tests. In 2011, Italy introduced a qualifications framework, known as the Quadro dei Titoli Italiani (QTI), which tied together, in a three-level system, both the new qualifications introduced as part of the Bologna Process and the older, pre-Bologna qualifications and which covers qualifications from university institutions and higher-education institutions for fine arts, music and dance (AFAM institutions).[75] In addition to academic degrees, many professional qualifications are tied to the QTI at the different levels.[76] The first level, tied to the first cycle of the Bologna Process, covers the laurea (bachelor's degree) in universities and the Diploma accademico di primo livello in AFAM institutions.[77] The older qualifications that map to this level are the Diploma universitario and the Diploma di scuole dirette a fini speciali (SDAFS) from universities, and the Diploma di Conservatorio, Diploma di Istituto Musicale Pareggiato, Diploma dell'Accademia di Belle Arti, Diploma dell'Istituto Superiore delle Industrie Artistiche (ISIA), Diploma dell'Accademia Nazionale di Danza and Diploma dell'Accademia Nazionale di Arte Drammatica from AFAM institutions.[78] The laurea is obtained after three years of study (180 ECTS credits) and confers the academic title of dottore;[77] the older university qualifications at this level took two to three years, with the three-year courses conferring the title of dottore.[78] The second level, tied to the second cycle of the Bologna Process, covers the laurea magistrale and the laurea specialistica of university institutions, and the Diploma accademico di secondo livello of AFAM institutions.[77] The old Diploma di laurea is mapped to this level.[78] The Laurea magistrale and the laurea specialistica are obtained after two further years of study (120 ECTS credits) and give the academic title of dottore magistrale.[77] The old Diploma di laurea took four to six years but was accessed directly from school, with a possible reduction by one year for those with a related diploma and also granted the title of dottore magistrale.[78] The third level, tied to the third cycle of the Bologna Process, covers the Dottorato di ricerca from university institutions and the Diploma accademico di formazione alla ricerca from AFAM institutions.[77] The old Dottorato di ricerca and Diploma di specializzazione are tied to this level.[78] The Dottorato di ricerca, under both new and old systems, takes a minimum of three years after the laurea magistralie/specialistica, and gives the academic titles of Dottore di Ricerca (Dott. Ric.) and PhD.[77][78] The old Diploma di specializzazione took two to six years and gave the academic title of Specialista.[78] Universities in Italy offer a number of other qualifications, including the Master universitario di primo livello (1 year/60 ECTS credits, 2nd cycle qualification) and the Master universitario di secondo livello (1 year/60 ECTS credits, 3rd cycle qualification), continuing from the laurea and the laurea magistrale/specialistica, respectively. These do not give access to the PhD. The Diploma di specializzazione, which is offered in a few specific professions, takes two to six years and gives the title of specialista. The Diploma di perfezionamento is a university certificate, aimed at professional training or in specific fields of study, which usually takes one year; it is not allocated a level in the framework.[79] AFAM institutions may offer the Diploma di perfezionamento o Master and Diploma accademico di specializzazione. These are one-year and two-year qualifications, respectively, and may be offered at the second cycle or third cycle level, distinguished by adding (I) or (II) after the qualification name. Higher schools for language mediators offer the Diploma di mediatore linguistico, a first-cycle degree that takes three years (180 ECTS credits), and which gives access to the laurea specialistica. Specialisation institutes/schools in psychoterapy offer the Diploma di specializzazione in psicoterapia, a third-cycle qualification that takes at least four years and requires a laurea magistrale/specialistica in either psychology or medicine and surgery, along with professional registration.[79] NetherlandsIn the Netherlands, the structure of academic studies was altered significantly in 1982 when the "Tweefasenstructuur" (Two Phase Structure) was introduced by the Dutch Minister of Education, Wim Deetman. With this structure an attempt was made to standardise all the different studies and to have them conform to similar timetables. An additional effect was that students would be forced to produce results within a preset time-frame or otherwise discontinue their studies. The two-phase structure has been adapted to a bachelor-master structure as a result of the Bologna process. AdmissionIn order for a Dutch student to get access to a university education, the student must complete a six-year pre-university secondary education called voorbereidend wetenschappelijk onderwijs (VWO). There are other routes possible, but only if the educational level of the applicant is comparable to that at the end of the standard two levels is access to university education granted. For some studies, specific end levels or disciplines are required, e.g., graduating without having studied physics, biology and chemistry will make it impossible to study medicine. People 21 years old, or older, who do not have the required entrance diplomas, may opt for an entrance exam to be admitted to a higher-educational curriculum. In this exam, they have to prove their command of disciplines considered necessary for pursuing such study. After 1 September 2002, they would be thus admitted to a Bachelor's curriculum, not to a Master's curriculum. For some disciplines[80][81] in the Netherlands, a governmentally determined limited access is in place (although under political review for abolishment, as of February 2011).[82] This limits the number of applicants to a specific course of study, thus trying to control the number of future graduates. The disciplines most renowned for their numerus clausus are medicine and dentistry. Every year a combination of the highest pre-university graduation grades and some additional conditions determine who can start such a numerus clausus course of study and who can not. Almost all Dutch universities are government supported, with only a few privately owned universities in existence (i.e. one in business and all others in theology). Leiden University is the oldest, founded in 1575. Pre-Bologna phases

Before the introduction of the bachelor-master structure, almost all academic studies in the Netherlands had the same length of four years and had two phases:

For medical students the "doctorandus" degree is not equivalent to the European Anglo Saxon postgraduate research degree in medicine, of MD (Medical Doctor). Besides the title doctorandus, the graduates of the Curius curriculum may also bear the title arts (physician). The doctorandus in medicine title is granted after four years (nominal time) of the Curius curriculum, while the title physician is granted after six years (nominal time) of that curriculum. The Dutch physician title is equal to a MSc degree according to the Bologna process and can be compared with the MBBS in the UK degree system and the North American MD, but not the UK MD degree, which is a research degree. One-on-one equivalence or interchangeability of the Dutch medical title and MD is often suggested. However, officially the MD title is not known, nor legal to use, in the Netherlands. The correct notation for a Dutch physician who completed his or her medical studies, but did not pursue a doctoral (PhD-like) study is "drs." (e.g. drs. Jansen, arts) and not "dr." in medicine, which is often used incorrectly. However, like in the United Kingdom, physicians holding these degrees are referred to as 'Doctor' by courtesy. In the Netherlands, there is the informal title dokter for physicians, but not doctor (dr.), unless they also earn such adegree by completing a PhD curriculum. Furthermore, the doctorandus degree does not give a medical student the right to treat patients; for this a minimum of two years of additional study (internship) is required. After obtaining a Medical Board registration, Dutch physicians must work an additional two to six years in a field of expertise to become a registered medical specialist. Dutch surgeons commonly are only granted access to surgical training and positions after obtaining a doctorate (PhD) successfully. In recent years, the six-year (nominal time) old Curius curriculum (which offered the titles doctorandus and physician) has been replaced with a three-year (nominal time) Bachelor Curius+ followed by a three-year (nominal time) Master Curius+. Those who had already begun their old-style Curius curriculum before that will still have to complete it as a six-year study (nominal time). A doctorandus in law uses the title meester (master, abbreviated as mr. Jansen) instead of drs., and some courses of study, such as in technology and agriculture< grant the title ingenieur (engineer, noted as ir. Jansen) instead of drs. These titles as equivalent to an LL.M (the title mr.) and to a MSc (the title ir.) and if gotten before 1 September 2002, from a recognized Dutch university, may be rendered as M (from Master) behind one's name, instead of using the typical Dutch honorifics before one's name. Since 1 September 2002, Dutch universities offer specific BSc, BA or LLB studies followed by MSc, MA or LLM studies, thus integrating into the international scientific community, offering lectures, other classes, seminars or complete curricula in English instead of Dutch. According to their field of study, MSc graduates may use either ir. or drs. before their names; MA graduates may use drs. before their name; LLM graduates may use mr. before their names, but only if they received such degrees from recognized Dutch universities. Not uncommonly, the Dutch "drs." abbreviation can cause much confusion in other countries, since it is perceived as a person who has a PhD in multiple disciplines. In the Netherlands, the degree MPhil was not awarded after 2009 as the Universiteiten van Nederland refused to recognize the MPhils awarded by Leiden University.[83] After successfully obtaining a "drs.", "ir." or "mr." degree, a student has the opportunity to follow a further, promotional course of study (informally called PhD) to eventually obtain a doctorate and subsequently the title "doctor". Promotion studies are ideally structured according to a preset time schedule of 4 to 6 years, during which the student has to be mentored by at least one professor. The promotion study has to be concluded with at least a scientific thesis, which has to be defended to "a gathering of his/her peers", in practice the board of the faculty with guest professors from other faculties or universities added. More and more common—and, in some disciplines, even mandatory—is that the student write, and have accepted for publication by peer-reviewed journals, original scientific work. The number of publications required is often debated and varies considerably between the various disciplines. However, in all disciplines the student is obligated to produce and publish a dissertation or thesis in book form. Bachelor/master structureAll current Dutch academic programs are offered under the Anglo-Saxon bachelor/master structure. It takes three years to earn a bachelor's degree and another one or two years to earn a master's degree. There are three official academic bachelor titles (BA, BSc and LLB) and three official master titles (MA, MSc and LLM). These academic titles are protected by the Dutch government. Using academic titlesAfter obtaining a doctorate, Dutch doctors may bear either the title dr. (lower case) before, or the letter D following, their name, but not both simultaneously.[84] There is no notation signifying the specific discipline in which the doctorate is obtained. As of 1 January 2021, the title 'PhD' and post-nominal degree 'PhD' can also be used, and these are also legally protected. Stacking of titles, as seen in countries such as Germany (Prof. Dr. Dr. Dr. Gruber), is highly uncommon in the Netherlands and not well received culturally. Those who have multiple doctoral titles may use dr.mult. before their name, but this is seldom seen in practice.[84] The honoris causa doctors may use dr.h.c. before their name.[84] Combining different Dutch titles, especially in different disciplines, is allowed, however, (e.g. mr. dr. Jansen, dr. mr. Jansen, dr. ir. Jansen, mr. ir. drs. Jansen, mr. ir. Jansen). The use of the combination ir. ing. is frequent, indicating one holds a HBO, vocational, or professional engineering degree, together with an academic engineering degree.[85] What is not allowed is, after obtaining a doctorate, using dr. drs. Jansen; dr. Jansen should be used instead. A combination of a Dutch title with an international title is not allowed, except for some limited number of international professional titles.[85] Thus, one should choose either one's classical Dutch title or use the shortcut provided by the law following one's name (since 1 September 2002 it is the other way around: those who hold Dutch degrees as MSc, LLM or MA may optionally use the old-style shortcuts before their names).[85][86] "Doctors" (dr.) can proceed to teach at universities as "universitair docent" (UD – assistant professor). With time, experience and achievement, this can evolve to a position as "universitair hoofddocent" (UHD – associate professor). Officially an UHD still works under the supervision of a "hoogleraar" (professor), the head of the department. However, this is not a given; it is also possible that a department is headed by a "plain" doctor, based on knowledge, achievement and expertise. The position of "hoogleraar" is the highest possible scientific position at a university and equivalent to the US "full" professor. The Dutch professor's title, noted as prof. Jansen or professor Jansen, is connected to one's employment. This means that, should the professor leave the university, he or she also loses the privilege to use the title of professor. Retired professors are an exception and may continue to note the title in front of their name, or use the title emeritus professor (em. prof.). People who switch to a non-university job lose their professorial title and are only allowed to use the "dr." abbreviation. Unlike some other European countries, such as Germany, Dutch academic titles are used rarely outside academia, hold no value in everyday life, and typically are not listed on official documentation (e.g. passport, drivers license, (governmental) communication). Dutch academic titles, however, are legally protected and can only be used by graduates from Dutch institutions of higher education. Illegal use is considered a misdemeanor and is subject to legal prosecution.[87][88] Holders of foreign degrees, therefore, need special permission before being able to use a recognised Dutch title, but they are free to use their own foreign title (untranslated).[89][90][91][92] In practice, the Public Department does not prosecute the illegal use of a protected title (the Netherlands applies prosecutorial discretion, so some known criminal uses are not prosecuted).[93] NorwayPrior to 1980, there were around 50 different degrees and corresponding educational programs within the Norwegian higher education system. Degrees had titles that included the gender based Latin term candidatus/candidata. The second part of the title usually consisted of a Latin word corresponding to the profession or training. For example, Cand. Mag. (Candidatus Magisterii) required 4 to 5 years, Cand. Real.[94] (Candidatus Realium) required 6 years of study and a scientific thesis in a select set of scientific disciplines (realia). Over the years these were replaced gradually with degrees that were more and more internationally comparable programs and corresponding titles. For example, the degree Cand. Scient. replaced Cand. Real. in the period 1985 to 2003. These degrees were all retired in 2003 in favour of an international system. The reform of higher education in Norway, Kvalitetsreformen ("The Quality Reform"), was passed in the Norwegian Parliament, the Storting, in 2001 and carried out during the 2003/2004 academic year. It introduced standard periods of study and the titles master and bachelor (baccalaureus). The system differentiates between a free master's degree and a master's degree in technology. The latter corresponds to the former sivilingeniør degree (not to be confused with a degree in civil engineering, which is but one of many degrees linked to the title sivilingeniør, which is still in use for new graduates who can choose to also use the old title). All pre-2001 doctoral degree titles were replaced with the title "Philosophical Doctor degree", written philosophiæ doctor (instead of the traditional doctor philosophiæ). The title dr. philos. is a substantially higher degree than the PhD[citation needed] and is reserved for those who qualify for such a degree without participating in an organized doctoral degree program. PolandIn Poland, the system is similar to the German one.

Russia, Ukraine and some other former USSR republicsSince 1992, Russian higher education has introduced a multilevel system, enabling higher education institutions to award and issue Bachelor of Science and Master of Science degrees.[95] In Russia, Ukraine and some other former USSR republics educational degrees are awarded after finishing a college education. There are several levels of education that one must choose in the 2nd and 3rd year of college, usually in the 3rd year of study.[96]

But a Specialist degree can appear equivalent to Magister degree by reason of taking an equivalent amount of time. Usually Specialist or Magister degrees incorporate the bachelor's degrees in them, but only the high-level degree is given on the final diploma. Specialist and Magister degrees require taking final state exams and producing written work on practical application of studied skills or research thesis (usually 70–100 pages) and is roughly equivalent to a master's degree.[98] The first-level academic degree is called Kandidat nauk ("Candidate of Sciences"). This degree requires extensive research, taking some classes, publications in peer-reviewed academic journals (not less than 5 publications in Ukraine or 3 publications in Russia), taking 3 or more exams (one or more in their speciality, one in a foreign language and one in the history and philosophy of science) and writing and defending an in-depth thesis (80–200 pages) called a "dissertation". Finally, there is a Doktor Nauk ("Doctor of Sciences") degree in Russia and some former USSR academic environments. This degree is granted for contributions in a certain field (formally – who established new direction or new field in science). It requires discovery of new phenomenon or development of new theory or essential development of new direction, etc. There is no equivalent of this "doctor of sciences" degree in the US academic system. It is roughly equivalent to Habilitation in Germany, France, Austria and some other European countries. In countries with a two-tier system of doctoral degrees, the degree of Kandidat Nauk should be considered for recognition at the level of the first doctoral degree. According to Guidelines for the recognition of Russian qualifications in the other countries,[99] in countries with a two-tier system of doctoral degrees, the degree of Doktor Nauk should be considered for recognition at the level of the second doctoral degree. In countries in which only one doctoral degree exists, the degree of Doktor Nauk should be considered for recognition at the level of this degree. According to International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED) UNESCO 2011,[100] par.262, for purposes of international educational statistics:

SpainSpain's higher-education legal framework includes official and accredited education, as well as non-official education. 1.1 Official and accredited education In Spain, accreditation of official university study programmes is regulated by law and monitored by governmental agencies responsible for verifying their quality and suitability for official approval and accreditation. Official professional study programmes lead to degree qualifications (Títulos) with full academic and professional rights. The degrees awarded in accordance with the latest higher-education system are: 1. Bachelor's Degree (Grado) – 240 ECTS Credits in 4 years. 2. Master's Degree (Master Universitario) – 60 to 120 ECTS Credits in 1–2 years. 3. Doctoral degree PhD (Doctorado) – in 3–4 years. Accredited bachelor's degrees and master's degrees qualifications will always be described as Grado and Master Universitario. These qualifications comply with the European Higher Education Area (EHEA)[101] framework. Officially approved and accredited university study programmes by law must implement this framework in order to attain and retain accreditation in Spain.  1.2 Non-official education Not all EHEA-compliant study programmes in Spain are officially approved or accredited by government agencies. Some universities offer proprietary study programmes as alternatives for a variety of reasons: serving the continuing education market for individual self-advancement and also providing higher education to individuals who have failed to acquire bachelor's degree qualifications. The main reason for offering these alternative studies, though, is the complex bureaucratic process required to receive the approval of specific titles, in particular when it refers to new studies or studies about matters that do not fit with the official studies. For historical reasons, the academic system has been very much under the control of the state, and private universities are still regarded with as a threat to the state system. These programmes fall within the category of "non officially approved and accredited" or estudios no oficiales, and they confer no academic or professional rights. This means that they do not entitle the bearer to claim to have any specific academic or professional qualifications, as far as the Spanish authorities are concerned. However, there may be private agreements to recognize the titles.  Universities offering non-official study programmes are legally bound to clearly differentiate between officially-approved and non-officially-approved qualifications. Non-accredited master's degrees will be described as just Master, without the accompanying Universitario. Certain non-officially approved and accredited study programmes may acquire a positive reputation. However, neither professional associations, government agencies, judiciary authorities, nor universities – other than the study programme provider – are obliged to recognize non-official qualifications in any way. 2. Accreditation system University-taught study programme accreditation is granted through the National Agency for Quality Assessment and Accreditation (ANECA),[102] a government-dependent quality assurance and accreditation provider for the Spanish higher education system that ensures that the data held in the Register of Universities, Centres and Qualifications (RUCT),[103] a national registry for universities and qualifications, is correct and up to date. All study programmes must be accredited by ANECA[102] prior to their inclusion in the RUCT.[103] The RUCT[103] records all officially approved universities and their bachelor's degrees, master's degrees and PhDs and each and every one of the officially approved and accredited study programmes. Universities are assigned a specific number Code (Código) by the RUCT. The same study programme may acquire different codes as it progresses through various stages of official approval by local and central governments. Prospective students should check the RUCT Code awarded to the study programme of their interest at every stage of their enquiries concerning degrees in Spain.[103] ANECA makes recommendations regarding procedures, staffing levels, quality of teaching, resources available to students and continuity or loss of accreditation. The ANECA Registry[104] records all events in the life of an officially approved and accredited study programme or a university. The ANECA Registry Search Facility[105] may be the simplest and safest way to verify the status of all officially approved and accredited study programmes in Spain. It is also possible to track qualifications by using the search facility that several Autonomous Communities' own accreditation agencies offer. These agencies work within the ANECA framework and generally show more detailed information about the study programmes available in each territory (e.g., Catalonia, Madrid, etc.) 3. Qualifications framework for higher education The qualifications framework for higher education MECES is the reference framework adopted in Spain in order to structure degree levels. Not all universities offer degrees named exactly the same, even if they have similar academic and professional effects. Each university may present proposals for the study programme considered to meet professional and academic demand. The proposal will consist of a report linking the study programme being considered and the proposed qualification to be awarded. This report will be assessed by ANECA and sent for the Consejo de Universidades Españolas.[106] If the Consejo agrees with ANECA's approval, it will be included in the RUCT and ANECA registries. 4. Spanish qualifications and their professional effects. All bachelor's and master's degrees accredited by ANECA bestow full academic and professional rights in accordance with new and previous laws. Professional-practice law in Spain is currently under revision. Sweden

SwitzerlandBefore the Bologna Process, the academic degree of a Licentiate was reached after 4 or 5 years of study.[107] Depending on the official language of the university, it was called Lizentiat (German), Licence (French) or licenza (Italian) and, according to the Bologna reform, is today considered equivalent to a master's degree.[108] A Licentiate with a predefined qualification gave access to the last stage of a further two or more years of studies (depending on the field) for a doctoral degree. Apart from this, most universities offered a postgraduate diploma requiring up to two years of study. French-speaking universities called them diplôme d'études approfondies DEA or DESS, the Italian-speaking university post laurea and German-speaking universities mostly Nachdiplomstudium (NDS). Today the federal legislation defines these postgraduate diplomas (60 ECTS credits) as Master of Advanced Studies (MAS) or Executive Master of Business Administration (EMBA) degrees. Universities may also offer the possibility to gain a diploma in advanced studies (DAS, less than 60 ECTS credits).[109] These degrees do not normally give access to a doctoral programme. United KingdomEngland, Wales and Northern Ireland An academic degree is protected under UK law. All valid UK degrees are awarded by universities or other degree-awarding bodies whose powers to do so are recognised by the UK government; hence they are known as "recognised bodies".[110] The standard first degree in England, Northern Ireland and Wales is the bachelor's degree conferred with honours. Usually this is a Bachelor of Arts (BA) or a Bachelor of Science (BSc) degree. Other variants exist: for example, Bachelor of Education or Bachelor of Laws. It usually takes three years to read for a bachelor's degree. The honours are usually categorised into four classes:

Candidates who have not achieved the standard for the award of honours may be admitted without honours to the "ordinary" bachelor's degree if they have met the required standard for this lesser qualification (also referred to as a "pass degree"). Standard levels for each of these classes are 70%+ for a first, 60–69% for a 2:1, 50–59% for a 2:2, 40–49% for a 3rd and 30%+ for a pass degree, although this can vary by institution (e.g. the Open University).[112] The foundation degree[113] is a qualification, lower than bachelor's level, awarded following a two-year programme of study that is usually vocational in nature. The foundation degree can be awarded by a university or college of higher education that has been granted foundation-degree-awarding powers by the UK government. This degree is comparable to an associate degree in the United States. The universities of Oxford and Cambridge award honorary Master of Arts (MA) degrees to graduates of their bachelor's programmes, following a specified period of time. This is comparable to the practice of the ancient universities in Scotland awarding an MA for a first degree and arguably reflects the rigorous standards expected of their graduates. Master's degrees[114] such as Master of Arts or Master of Science are typically awarded to students who have undertaken at least a year of full-time postgraduate study, which may require study and involve an element of research. Degrees such as Master of Philosophy (MPhil) or Master of Letters/Literature (MLitt) are likely to be awarded for postgraduate study involving original research. A student undertaking a master's would normally be expected to already hold a bachelor's degree in a relevant subject, hence the possibility of reaching the master's level in one year. Some universities award a master's as a first degree following an integrated programme of study (an 'integrated master's degree'). These degrees are usually designated by the subject, such as Master of Engineering for engineering, Master of Physics for physics, Master of Mathematics for mathematics and so on; it usually takes four years to read for them. Graduation to these degrees is always with honours. Master of Engineering in particular has now become the standard first degree in engineering at the top UK universities, replacing the older Bachelor of Engineering. Master's degrees are often graded as:

The Master of Business Administration (MBA) degree is highly valued by those seeking to advance in business as managers and decision makers. Doctoral degrees or doctorates,[115] such as the Doctor of Philosophy degree (PhD or DPhil) or Doctor of Education (EdD or DEd), are awarded following a programme of original research that contributes new knowledge within the context of the student's discipline. Doctoral degrees usually take three years full-time. Therefore, in the UK it may only take seven years to progress from undergraduate to earning a doctorate – in some cases six, since having a master's is not always a precondition for embarking on a doctoral degree. This contrasts with nine years in the United States, reflecting differences in the educational systems. Some doctorates, such as the Doctor of Clinical Psychology (DClinPsy) qualification, confirm competence to practice in particular professions. There are also higher doctorates – Doctor of Science (DSc) and Doctor of Letters/Literature (DLitt) — that are typically awarded to experienced academics who have demonstrated a high level of achievement in their academic career; for example, they may have published widely on their subject or become professors in their fields. UK post-secondary qualifications are defined at different levels, with levels 1–3 denoting further education and levels 4–8 denoting higher education. Within this structure, a foundation degree is at level 5; a bachelor's degree at level 6; a master's degree at level 7; and a doctoral degree at level 8.[116] Full information about the expectations for different types of UK degrees is published by the Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education.[117] See also graduate certificate, graduate diploma, postgraduate certificate, postgraduate diploma and British degree abbreviations. ScotlandThe standard first degree for students studying arts or humanities in Scotland is either a Bachelor of Arts or a Master of Arts (the latter traditionally awarded by the Ancient Universities of Scotland for a first degree in an arts/humanities subject). The standard undergraduate degree for natural and social science subjects is the Bachelor of Science.[118] Students can work towards a first degree at either ordinary or honours level. A general or ordinary degree (BA/MA or BSc) takes three years to complete; an honours degree (BA/MA Hons or BSc Hons) takes four years. The ordinary degree need not be in a specific subject, but can involve study across a range of subjects within (and sometimes beyond) the relevant faculty, in which case it may also be called a general degree. If a third year or junior honours subject is included, the ordinary degree in that named discipline is awarded. The honours degree involves two years of study at a sub-honours level in which a range of subjects within the relevant faculty are studied and then two years of study at honours level which is specialised in a single field (for example classics, history, chemistry, biology, etc.). Not all universities in Scotland adhere to this; in some, one studies in several subjects within a faculty for three years and can then specialise in two areas and attain a joint honours degree in fourth year. This also reflects the broader scope of the final years of Scottish secondary education, where traditionally five Highers are studied, compared to (typically) three English or Welsh A-Levels. The Higher is a one-year qualification, as opposed to the two years of A-Levels, which accounts for Scottish honours degrees being a year longer than those in England. Advanced Highers add an optional final year of secondary education, bringing students up to the level of their A-Level counterparts – students with strong A-Levels or Advanced Highers may be offered entry directly into the second year at Scottish universities. Honours for MA or bachelor's degrees are classified into three classes:

Students who complete all the requirements for an honours degree, but who do not receive sufficient merit to be awarded third-class honours, may be awarded a Special Degree (ordinary degree – bachelor's level SCQF Level 9). In most respects, the criteria for awarding qualifications at honours level and above are the same as in the rest of the UK (see above under England, Wales and Northern Ireland). Postgraduate qualifications are not designated Master of Arts, as in the rest of the UK, as this is an undergraduate degree. Postgraduate degrees in arts and humanities subjects are usually designated Master of Letters (M.Litt.) or, in natural and social sciences, Master of Science (M.Sc.). Non-doctoral postgraduate research degrees are usually designated Master of Philosophy (M.Phil.) or Master of Research (M.Res.). The postgraduate teaching qualification is the Postgraduate Diploma in Education (PGDE). Postgraduate qualifications are classified into four classes:

North AmericaCanadaIn Canada, education is the responsibility of the provinces and territories, rather than the federal government. However, all of Canada follows the three-level bachelor's-master's-doctorate system common to the Anglophone world, with a few variations. A common framework for degrees was agreed between the provinces and territories in 2007.[119] Bachelor's degrees take normally three to four years, more commonly three years in Quebec (where they follow on from college courses rather than directly from secondary education). Outside Quebec, three-year bachelor's degrees are normally ordinary degrees, while four-year bachelor's degrees are honours degrees; an honours degree is normally needed for further study at the master's level.[120] Master's degrees take one to three years (in Quebec they normally take one and a half to two years). Doctorates take a minimum of three years. Alone among Canadian provinces and territories, British Columbia offers two-year associate degrees, allowing credit to be transferred into a four-year bachelor's program.[121] In Canada, first professional degrees such as DDS, MD, PharmD and LLB or JD are considered bachelor's level qualifications, despite their often being named as if they were doctorates.[119][122][123][124][125][126] QuebecIn the province of Quebec, the majority of students must attend college prior to entering university. Upon completion of a two-year pre-university program, such as in sciences or humanities, or a three-year technical program, such as nursing or computer science, college graduates obtain a college diploma, which is a prerequisite for access to university-level studies. Although these college programs are typical, they are not offered in every institution in the province. Moreover, while a few other pre-university programs with various concentrations exist, many other technical/career programs are available, depending on the college of choice. For example, Dawson College in Montreal has nearly sixty different programs leading to a college diploma. Special programs, such as physical rehabilitation therapy, are offered in some colleges as well. These programs allow students to enter professional university programs, such as physiotherapy (which consists of an integrated Bachelor of Science in Physiotherapy and Master of Physical Therapy), without having to meet the usual grade and course prerequisites required from students holding a pre-university science diploma. A similar option is offered for college nursing graduates as they can pursue their studies in university to obtain a Bachelor of Nursing in two years (rather than the usual three or four years, depending on whether the student has completed a college diploma in Quebec). Additionally, whereas aspiring medical students are usually required to complete an undergraduate degree before applying to medical schools, Quebec college graduates have the option to enter: