RNA誘導サイレンシング複合体 (RNAゆうどうサイレンシングふくごうたい、英 : RNA-induced silencing complex 、略称: RISC )は、タンパク質複合体 、リボヌクレオタンパク質 であり、転写 や翻訳 段階においてさまざまな経路を介して遺伝子サイレンシング を行う機能を持つ[ 1] miRNA などの一本鎖RNA 断片や二本鎖のsiRNA を利用して、遺伝子調節の重要なツールとして機能する[ 2] 相補的 なmRNA 転写産物を認識する際の鋳型として機能し、相補的なmRNAが見つかると、RISCを構成するタンパク質の1つであるArgonaute がmRNAを切断する。この過程はRNA干渉 (RNAi)と呼ばれ、多くの真核生物 でみられる。RNAiは二本鎖RNA(dsRNA)の存在によって開始されるため、ウイルス 感染に対する防御の重要な過程として機能する[ 1] [ 3] [ 4]

RISCの生化学的な同定は、コールド・スプリング・ハーバー研究所 のグレゴリー・ハノン (英語版 ) [ 5] アンドリュー・ファイアー とクレイグ・メロー によるのRNAiの発見(1998年)からわずか2年後のことであった[ 3]

キイロショウジョウバエDrosophila melanogaster ハノンらは、ショウジョウバエ Drosophila の細胞において、dsRNAによる遺伝子サイレンシング に関与するRNAi機構の同定を試みており、ショウジョウバエS2細胞 (英語版 ) lacZ ベクター でトランスフェクション し、β-ガラクトシダーゼ 活性によって遺伝子発現 の定量を試みた。lacZ のdsRNAを共にトランスフェクションすると、コントロールdsRNAの場合と比較して、β-ガラクトシダーゼ活性が大きく低下した。ここから、dsRNAは配列の相補性を利用して遺伝子発現を制御していることが示された。

その後、ショウジョウバエのサイクリンE をコードするdsRNAを用いてS2細胞のトランスフェクションが行われた。サイクリンEは細胞周期 のS期 への進行に必要不可欠な因子であるが、サイクリンEのdsRNAは細胞周期をG1 期 (S期の前の段階)で停止させた。ここから、RNAiは内因性遺伝子を標的とすることができることが示された。

さらに、サイクリンEのdsRNAはサイクリンEのmRNAのみを減少させ、同様の結果は細胞周期のS期、G2 期 、M期 に作用するサイクリンA のdsRNAを用いた場合でも示された。このことは、RNAiの特徴である、加えられたdsRNAに対応するmRNAのレベルが低下することを示している。

mRNAレベルの低下が(他の系でのデータから示唆されるように)直接的な標的化の結果であるのかどうかを確かめるため、ショウジョウバエS2細胞をサイクリンEまたはlacZ のいずれかのdsRNAでトランスフェクションを行い、その後サイクリンEまたはlacZ の合成mRNAをインキュベーションした。その結果、サイクリンEのdsRNAでトランスフェクションを行った細胞でのみサイクリンE転写産物が分解され、一方lacZ 転写産物は安定であった。逆に、lacZ のdsRNAでトランスフェクションを行った細胞のみlacZ 転写産物が分解され、サイクリンE転写産物は安定であった。これらの結果に基づいてハノンらは、RNAi機構は配列特異的なヌクレアーゼ 活性によって標的mRNAを分解していることを示唆した。彼らはそのヌクレアーゼ活性を担う酵素をRISCと命名した[ 5]

dsRNAと複合体を形成したArgonauteタンパク質のPIWIドメイン

RNase III (英語版 ) Dicer は、二本鎖のsiRNAや一本鎖のmiRNAを産生することでRNAi過程を開始する、RISCの重要なメンバーである。細胞内でのdsRNAの酵素的切断によって、長さは21–23ヌクレオチドで3'末端に2ヌクレオチドのオーバーハングを持つ、短いsiRNA断片が形成される[ 6] [ 7] [ 8] [ 9] [ 10] [ 11] [ 12] [ 13]

熱力学的安定性の低い5'末端を持つ鎖がArgonaute タンパク質によって選択され、RISCに取り込まれる[ 11] [ 14]

もう一方の鎖はパッセンジャー鎖と呼ばれ、RISCによって分解される[ 15] RNAi経路の一部を示した図。RISCはさまざまな経路でmRNAを介した遺伝子のサイレンシングを行う。

RISCの主要なタンパク質であるAgo2 (英語版 ) SND1 (英語版 ) AEG-1 は、遺伝子サイレンシング機能に重要な役割を果たす[ 16]

RISCはmiRNAまたはsiRNAのガイド鎖を用いて、ワトソン・クリック型の塩基対形成によってmRNA転写産物の3' UTRの相補的領域を標的とし、さまざまな方法によるmRNA転写産物からの遺伝子発現の調節を可能にする[ 1] [ 17]

RISCの最もよく解明されている機能は、標的mRNAの分解によってリボソーム による翻訳 に利用される転写産物の量を減少させることである。Argonauteによる、RISCのガイド鎖に相補的なmRNAのエンドヌクレアーゼ 的切断は、RNAiの開始に重要である[ 18]

ガイド鎖と標的mRNA配列とのほぼ完全な相補性

「スライサー」(slicer)と呼ばれる標的mRNA切断活性を持つArgonauteタンパク質の存在[ 1] mRNAの切断が行われた後の分解には、2つの主要な経路が存在する。どちらもmRNAのポリ(A)テール の分解によって開始され、mRNAの5'キャップ の除去が行われる。

RISCは翻訳時のリボソームや補助因子のローディングを調節し、結合したmRNA転写産物の発現を抑制することができる。翻訳抑制には、ガイド鎖と標的mRNAとの配列の相補性は部分的なものでよい[ 1]

翻訳開始後段階での調節

ペプチドの分解

翻訳中のリボソームの上流での終結の促進[ 21]

伸長反応の遅延[ 22] 開始段階での翻訳抑制と開始後段階での抑制が相互排他的であるのかについては、いまだ推測の域を出ていない。

一部のRISCはゲノムを直接的に標的化することができ、特定の遺伝子座 へヒストンメチルトランスフェラーゼ をリクルートしてヘテロクロマチン を形成し、遺伝子のサイレンシングを行うことができる。こうしたRISCはRNA誘導転写サイレンシング (英語版 ) [ 1] [ 23] [ 24]

RITSはセントロメア リピート配列を認識し、ヘテロクロマチンの形成を指示することが示されている。siRNA(ガイド鎖)と転写新生鎖との塩基対形成によって、特定の染色体領域へRITS、そしてヒストン修飾酵素 がリクルートされると考えられている[ 25]

RITSは新生mRNA転写産物を分解するが、その機構の詳細は解明されていない。この機構は、分解された新生転写産物がRNA依存性RNAポリメラーゼ (RdRp)によって利用され、より多くのsiRNAが形成される、という自己増幅型のフィードバックループとして作用することが示唆されている[ 26]

分裂酵母 とシロイヌナズナ では、DicerによるdsRNAのsiRNAへのプロセシングは、ヘテロクロマチン形成による遺伝子サイレンシング経路を開始する。AGO4と呼ばれるArgonauteタンパク質は、ヘテロクロマチン配列を定義する低分子RNAと相互作用する。ヒストンメチルトランスフェラーゼはヒストンH3 (H3K9)をメチル化し、メチル化部位にクロモドメイン タンパク質をリクルートする。ヘテロクロマチンが確立され拡大するにつれて、DNAのメチル化 によって遺伝子のサイレンシングが維持される[ 27]

テトラヒメナ では、RISCによって形成されたsiRNAは体細胞での大核 の発生時にDNAを分解する役割を持っているようである。この機構は上述のヘテロクロマチン形成機構と類似しており、侵入してきた遺伝的エレメントに対する防御として機能することが示唆されている[ 27]

分裂酵母やシロイヌナズナにおけるヘテロクロマチン形成と同様に、テトラヒメナでもArgonauteファミリーのTwi1pがinternal elimination sequence(IES)と呼ばれる標的配列のDNAの除去を触媒する。メチルトランスフェラーゼやクロモドメインタンパク質によって、IESはヘテロクロマチン化されてDNAから除去される[ 27]

RISCの完全な構造は未解明である。多くの研究によってRISCのサイズと構成要素に関してさまざまな報告がなされているが、これは多数のRISC複合体が存在するためであるのか、研究によって異なる細胞や組織から精製が行われているためであるのか、完全には明らかにされていない[ 28]

RISCの組み立てと機能に関係する複合体[ 28]

複合体

由来

既知の構成要素

推定サイズ

RNAi経路における推定機能

Dcr2-R2D2[ 29]

D. melanogaster S2細胞Dcr2 , R2D2~250 kDa

dsRNAのプロセシング、siRNAの結合

RLC (A)[ 30] [ 31]

D. melanogaster 胚Dcr2, R2D2

NR

dsRNAのプロセシング、siRNAの結合、RISCの前駆体

Holo-RISC[ 30] [ 31]

D. melanogaster 胚Ago2 (英語版 ) Fmr1 /Fxr (英語版 ) ~80S

標的RNAへの結合と切断

RISC[ 5] [ 32] [ 33] [ 34]

D. melanogaster S2細胞Ago2, Fmr1/Fxr, Tsn, Vig

~500 kDa

標的RNAへの結合と切断

RISC[ 35]

D. melanogaster S2細胞Ago2

~140 kDa

標的RNAへの結合と切断

Fmr1-associated complex[ 36]

D. melanogaster S2細胞L5 (英語版 ) L11 (英語版 ) 5S rRNA , Fmr1/Fxr, Ago2, Dmp68 (英語版 ) NR

標的RNAへの結合と切断の可能性

Minimal RISC[ 37] [ 38] [ 39] [ 40]

HeLa細胞 eIF2C1 (英語版 ) ~160 kDa

標的RNAへの結合と切断

miRNP[ 41] [ 42]

HeLa細胞

eIF2C2 (Ago2), Gemin3 (英語版 ) Gemin4 (英語版 )

~550 kDa

miRNAの結合、標的RNAへの結合と切断

Ago, Argonaute; Dcr, Dicer; Dmp68, D. melanogaster orthologue of mammalian p68 RNA unwindase; eIF2C1, eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2C1; eIF2C2, eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2C2; Fmr1/Fxr, D. melanogaster orthologue of the fragile-X mental retardation protein; miRNP, miRNA-protein complex; NR, not reported; Tsn, Tudor-staphylococcal nuclease; Vig, vasa intronic gene.

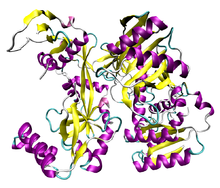

古細菌Pyrococcus furiosus のArgonauteタンパク質全長の構造

Argonauteタンパク質は、原核生物と真核生物にみられるタンパク質ファミリーである。原核生物における機能は不明であるが、真核生物ではRNAiに関与している[ 43] [ 40]

RISCローディング複合体は、Dicerによって形成されたdsRNA断片のAgo2へのローディングを(TRBPの助けを借りて)可能にする。

RISCローディング複合体(RLC)は、dsRNAをRISCへロードするために必要不可欠な構造体である。RLCにはDicer、TRBP (英語版 )

Dicer はRNase III型エンドヌクレアーゼ であり、RNAiを指示するためにロードされるdsRNA断片を形成する。TRBP は、3つのdsRNA結合ドメインを持つタンパク質である。Ago2 はRNaseであり、RISCの触媒中心である。DicerとTRBP、Ago2との結合は、Dicerによって形成されたdsRNAのAgo2への移行を促進する[ 44] [ 45] DHX9 (英語版 ) [ 46]

近年同定されたRISCのメンバーには、SND1 (英語版 ) MTDH がある[ 47] SND1 とMTDH はがん遺伝子 であり、さまざまな遺伝子の発現を調節する[ 48]

Ago, Argonaute; Dcr, Dicer; Dmp68, D. melanogaster orthologue of mammalian p68 RNA unwindase; eIF2C1, eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2C1; eIF2C2, eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2C2; Fmr1/Fxr, D. melanogaster orthologue of the fragile-X mental retardation protein; Tsn, Tudor-staphylococcal nuclease; Vig, vasa intronic gene.

miRNAとRISCの活性の模式図 活性化されたRISC複合体が細胞内のmRNA標的をどのように見つけているのかに関しては未解明であるが、この過程はmRNAからタンパク質への翻訳が起こっていない状況でも行われることが示されている[ 50]

後生動物 において内因的に発現しているmiRNAは通常、完全な相補性は持たない多くの遺伝子に対して作用し、そのため遺伝子発現の調節は翻訳抑制によって行われる[ 51] [ 52] [ 53]

^ a b c d e f “The RNA-induced silencing complex: A versatile gene-silencing machine” . Journal of Biological Chemistry 284 (27): 17897–17901. (2009). doi :10.1074/jbc.R900012200 . PMC 2709356 . PMID 19342379 . https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2709356/ .

^ a b “Mechanisms of post-transcriptional regulation by microRNAs: are the answers in sight?”. Nature Reviews Genetics 9 (2): 102–114. (2008). doi :10.1038/nrg2290 . PMID 18197166 .

^ a b

“Potent and specific genetic interference by double-stranded RNA in Caenorhabditis elegans ”. Nature 391 (6669): 806–811. (1998). Bibcode : 1998Natur.391..806F . doi :10.1038/35888 . PMID 9486653 .

^

Watson, James D. (2008). Molecular Biology of the Gene . San Francisco, CA: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. pp. 641–648. ISBN 978-0-8053-9592-1

^ a b c d

“An RNA-directed nuclease mediates post-transcriptional gene silencing in Drosophila cells”. Nature 404 (6775): 293–296. (2000). Bibcode : 2000Natur.404..293H . doi :10.1038/35005107 . PMID 10749213 .

^ “RNAi: double-stranded RNA directs the ATP-dependent cleavage of mRNA at 21 to 23 nucleotide intervals”. Cell 101 (1): 25–33. (2000). doi :10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80620-0 . PMID 10778853 . ^ “The contributions of dsRNA structure to Dicer specificity and efficiency” . RNA 11 (5): 674–682. (2005). doi :10.1261/rna.7272305 . PMC 1370754 . PMID 15811921 . https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1370754/ . ^ Hutvagner, Gyorgy (2005). “Small RNA asymmetry in RNAi: Function in RISC assembly and gene regulation” (英語). FEBS Letters 579 (26): 5850–5857. doi :10.1016/j.febslet.2005.08.071 . ISSN 1873-3468 . PMID 16199039 . ^ “Asymmetry in the assembly of the RNAi enzyme complex”. Cell 115 (2): 199–208. (2003). doi :10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00759-1 . PMID 14567917 . ^ “Functional siRNAs and miRNAs exhibit strand bias”. Cell 115 (2): 209–216. (2003). doi :10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00801-8 . PMID 14567918 . ^ a b “On the road to reading the RNA-interference code”. Nature 457 (7228): 396–404. (2009). Bibcode : 2009Natur.457..396S . doi :10.1038/nature07754 . PMID 19158785 .

^ Preall, Jonathan B.; Sontheimer, Erik J. (2005-11-18). “RNAi: RISC Gets Loaded” (英語). Cell 123 (4): 543–545. doi :10.1016/j.cell.2005.11.006 . ISSN 0092-8674 . PMID 16286001 . ^ “RNA interference overview | Abcam ”. www.abcam.com . 2021年3月7日 閲覧。 ^ Preall, Jonathan B.; He, Zhengying; Gorra, Jeffrey M.; Sontheimer, Erik J. (2006-03-07). “Short Interfering RNA Strand Selection Is Independent of dsRNA Processing Polarity during RNAi in Drosophila” (English). Current Biology 16 (5): 530–535. doi :10.1016/j.cub.2006.01.061 . ISSN 0960-9822 . PMID 16527750 . ^ “Human RISC couples microRNA biogenesis and posttranscriptional gene silencing”. Cell 123 (4): 631–640. (2005). doi :10.1016/j.cell.2005.10.022 . PMID 16271387 . ^ Santhekadur, Prasanna K.; Kumar, Divya P. (2020-06-01). “RISC assembly and post-transcriptional gene regulation in Hepatocellular Carcinoma” (英語). Genes & Diseases 7 (2): 199–204. doi :10.1016/j.gendis.2019.09.009 . ISSN 2352-3042 . PMC 7083748 . PMID 32215289 . https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7083748/ . ^ a b “Let-7 microRNA-mediated mRNA deadenylation and translational repression in a mammalian cell-free system” . Genes & Development 21 (15): 1857–1862. (2007). doi :10.1101/gad.1566707 . PMC 1935024 . PMID 17671087 . https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1935024/ .

^ a b ORBAN, TAMAS I.; IZAURRALDE, ELISA (April 2005). “Decay of mRNAs targeted by RISC requires XRN1, the Ski complex, and the exosome” . RNA 11 (4): 459–469. doi :10.1261/rna.7231505 . ISSN 1355-8382 . PMC 1370735 . PMID 15703439 . https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1370735/ .

^ “Argonaute2/RISC resides in sites of mammalian mRNA decay known as cytoplasmic bodies”. Nature Cell Biology 7 (6): 633–636. (2005). doi :10.1038/ncb1265 . PMID 15908945 . ^ “MicroRNA silencing through RISC recruitment of eIF6”. Nature 447 (7146): 823–828. (2007). Bibcode : 2007Natur.447..823C . doi :10.1038/nature05841 . PMID 17507929 . ^ “Short RNAs repress translation after initiation in mammalian cells”. Molecular Cell 21 (4): 533–542. (2006). doi :10.1016/j.molcel.2006.01.031 . PMID 16483934 . ^ “Evidence that microRNAs are associated with translating messenger RNAs in human cells”. Nature Structural & Molecular Biology 13 (12): 1102–1107. (2006). doi :10.1038/nsmb1174 . PMID 17128271 . ^ “RNAi-mediated targeting of heterchromatin by the RITS complex” . Science 303 (5658): 672–676. (2004). Bibcode : 2004Sci...303..672V . doi :10.1126/science.1093686 . PMC 3244756 . PMID 14704433 . https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3244756/ . ^ “RITS acts in cis to promote RNA interference-mediated transcription and post-transcriptional silencing”. Nature Genetics 36 (11): 1174–1180. (2004). doi :10.1038/ng1452 . PMID 15475954 . ^ Shimada, Yukiko; Mohn, Fabio; Bühler, Marc (2016-12-01). “The RNA-induced transcriptional silencing complex targets chromatin exclusively via interacting with nascent transcripts” . Genes & Development 30 (23): 2571–2580. doi :10.1101/gad.292599.116 . ISSN 0890-9369 . PMC 5204350 . PMID 27941123 . https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5204350/ . ^ “RNA-dependent RNA polymerase is an essential component of a self-enforcing loop coupling heterochromatin assembly to siRNA production” . Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 102 (1): 152–157. (2005). doi :10.1073/pnas.0407641102 . PMC 544066 . PMID 15615848 . https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC544066/ . ^ a b c “Small RNAs in genome arrangement in Tetrahymena ”. Current Opinion in Genetics & Development 14 (2): 181–187. (2004). doi :10.1016/j.gde.2004.01.004 . PMID 15196465 .

^ a b c Sontheimer EJ (2005). “Assembly and function of RNA silencing complexes”. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 6 (2): 127–138. doi :10.1038/nrm1568 . PMID 15654322 .

^ a b “R2D2, a bridge between the initiation and effector steps of the Drosophila RNAi pathway”. Science 301 (5641): 1921–1925. (2003). Bibcode : 2003Sci...301.1921L . doi :10.1126/science.1088710 . PMID 14512631 .

^ a b c d e f g h i j “A Dicer-2-dependent 80S complex cleaves targeted mRNAs during RNAi in Drosophila ”. Cell 117 (1): 83–94. (2004). doi :10.1016/S0092-8674(04)00258-2 . PMID 15066284 .

^ a b c d “RISC assembly defects in the Drosophila RNAi mutant armitage ”. Cell 116 (6): 831–841. (2004). doi :10.1016/S0092-8674(04)00218-1 . PMID 15035985 .

^ a b c “Argonaute2, a link between genetic and biochemical analyses of RNAi”. Science 293 (5532): 1146–1150. (2001). doi :10.1126/science.1064023 . PMID 11498593 .

^ a b c “Fragile X-related protein and VIG associate with the RNA interference machinery” . Genes & Development 16 (19): 2491–2496. (2002). doi :10.1101/gad.1025202 . PMC 187452 . PMID 12368260 . https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC187452/ .

^ a b “A micrococcal nuclease homologue in RNAi effector complexes”. Nature 425 (6956): 411–414. (2003). Bibcode : 2003Natur.425..411C . doi :10.1038/nature01956 . PMID 14508492 .

^ a b “Biochemical identification of Argonaute 2 as the sole protein required for RNA-induced silencing complex activity” . Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 101 (40): 14385–14389. (2004). Bibcode : 2004PNAS..10114385R . doi :10.1073/pnas.0405913101 . PMC 521941 . PMID 15452342 . https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC521941/ .

^ a b c d e “A Drosophila fragile X protein interacts with components of RNAi and ribosomal proteins” . Genes & Development 16 (19): 2497–2508. (2002). doi :10.1101/gad.1022002 . PMC 187455 . PMID 12368261 . https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC187455/ .

^ a b c “Single-stranded antisense siRNAs guide target RNA cleavage in RNAi”. Cell 110 (5): 563–574. (2002). doi :10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00908-X . hdl :11858/00-001M-0000-0012-F2FD-2 PMID 12230974 .

^ a b “Argonaute2 is the catalytic engine of mammalian RNAi”. Science 305 (5689): 1437–1441. (2004). Bibcode : 2004Sci...305.1437L . doi :10.1126/science.1102513 . PMID 15284456 .

^ “RISC is a 5′ phosphomonoester-producing RNA endonuclease” . Genes & Development 18 (9): 975–980. (2004). doi :10.1101/gad.1187904 . PMC 406288 . PMID 15105377 . https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC406288/ . ^ a b c “Human Argonaute2 mediates RNA cleavage targeted by miRNAs and siRNAs”. Molecular Cell 15 (2): 1403–1408. (2004). doi :10.1016/j.molcel.2004.07.007 . PMID 15260970 .

^ a b c “miRNPs: a novel class of ribonucleoproteins containing numerous microRNAs” . Genes & Development 16 (6): 720–728. (2002). doi :10.1101/gad.974702 . PMC 155365 . PMID 11914277 . https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC155365/ .

^ a b c d “A microRNA in a multiple-turnover RNAi enzyme complex”. Science 297 (5589): 2056–2060. (2002). Bibcode : 2002Sci...297.2056H . doi :10.1126/science.1073827 . PMID 12154197 .

^ Hall TM (2005). “Structure and function of Argonaute proteins”. Cell 13 (10): 1403–1408. doi :10.1016/j.str.2005.08.005 . PMID 16216572 . ^ “TRBP recruits the Dicer complex to Ago2 for microRNA processing and gene silencing” . Nature 436 (7051): 740–744. (2005). Bibcode : 2005Natur.436..740C . doi :10.1038/nature03868 . PMC 2944926 . PMID 15973356 . https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2944926/ . ^ “Structural insights into RNA processing by the human RISC-loading complex” . Nature Structural & Molecular Biology 16 (11): 1148–1153. (2009). doi :10.1038/nsmb.1673 . PMC 2845538 . PMID 19820710 . https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2845538/ . ^ “Structural insights into RISC assembly facilitated by dsRNA-binding domains of human RNA helices A (DHX9)” . Nucleic Acids Research 41 (5): 3457–3470. (2013). doi :10.1093/nar/gkt042 . PMC 3597700 . PMID 23361462 . https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3597700/ . ^ “Increased RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) activity contributes to hepatocellular carcinoma” . Hepatology 53 (5): 1538–1548. (2011). doi :10.1002/hep.24216 . PMC 3081619 . PMID 21520169 . https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3081619/ . ^ “Astrocyte elevated gene (AEG-1): a multifunctional regulator of normal and abnormal physiology” . Pharmacology & Therapeutics 130 (1): 1–8. (2011). doi :10.1016/j.pharmthera.2011.01.008 . PMC 3043119 . PMID 21256156 . https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3043119/ . ^ “An siRNA ribonucleoprotein is found associated with polyribosomes in Trypanosoma brucei ” . RNA 9 (7): 802–808. (2003). doi :10.1261/rna.5270203 . PMC 1370447 . PMID 12810914 . https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1370447/ . ^ “mRNA translation is not a prerequisite for small interfering RNA-mediated mRNA cleavage”. Differentiation 73 (6): 287–293. (2005). doi :10.1111/j.1432-0436.2005.00029.x . PMID 16138829 . ^ “Anti-viral RNA silencing: do we look like plants?” . Retrovirology 3 : 3. (2006). doi :10.1186/1742-4690-3-3 . PMC 1363733 . PMID 16409629 . https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1363733/ . ^ Bartel DP (2009). “MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions” . Cell 136 (2): 215–233. doi :10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.002 . PMC 3794896 . PMID 19167326 . https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3794896/ . ^ “MicroRNAs and their regulator roles in plants”. Annual Review of Plant Biology 57 : 19–53. (2006). doi :10.1146/annurev.arplant.57.032905.105218 . PMID 16669754 .