|

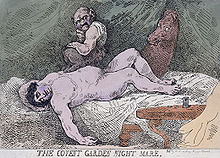

The Nightmare

The Nightmare is a 1781 oil painting by the Swiss artist Henry Fuseli. It shows a woman with her arms thrown below her, in deep sleep as she undergoes a nightmare as an almost hidden horse (the "night-mare") looks on as a demonic and ape-like incubus crouches on her chest.[1] Its erotic and haunting evocation of obsession became a breakthrough success for Fuseli. Critics were taken aback by its overt sexuality, since interpreted as anticipating Jungian ideas about the unconscious. Although Fuseli had unsuccessfully exhibited at the Royal Academy of London many times earlier, critics reacted with horrified fascination when it was shown at his 1782 showing, and the Nightmare became his first commercially successful work. The image became popular to the extent that he produced at least three other versions, engraved versions became widely distributed, it was parodied in political satire, and became a frequent source for 18th-century Gothic fiction authors such as Mary Shelley. DescriptionThe Nightmare simultaneously offers both the image of a dream—by indicating the effect of the nightmare on the woman—and a dream image—in symbolically portraying the sleeping vision.[2] It depicts a sleeping woman draped over the end of a bed with her head hanging down, exposing her long neck. She is mounted by an incubus that peers out at the viewer. The sleeper seems lifeless and lies on her back in a position that produces nightmares.[3] Her brilliant colouration is set against the darker reds, yellows and ochres of the background; Fuseli used a chiaroscuro effect to create strong contrasts between light and shade. The interior is contemporary and fashionable and contains a small table on which rests a mirror, phial, and book. The room is hung with red velvet curtains which drape behind the bed. Emerging from a parting in the curtain is the head of a horse with bold, pupil-less eyes.[4] The relationship of the incubus and the horse (mare) evokes the notion of nightmares. The work was likely inspired by the waking dreams experienced by Fuseli and his contemporaries, who found that these experiences related to folkloric beliefs like the Germanic tales about demons and witches that possessed people who slept alone. In these stories, men were visited by horses or hags, giving rise to the terms "hag-riding" and "mare-riding", and women were believed to engage in sex with the devil.[5] The etymology of the word "nightmare" is derived from mara, a Scandinavian mythological term referring to a spirit sent to torment or suffocate sleepers. The early meaning of nightmare included the sleeper's experience of weight on the chest combined with sleep paralysis, dyspnea, or a feeling of dread.[6] Sleep and dreams were common subjects for Fuseli, although The Nightmare is unique among his paintings for its lack of reference to literary or religious themes (Fuseli was an ordained minister).[7] His first known painting was Joseph Interpreting the Dreams of the Butler and Baker of Pharaoh (1768), and later he produced The Shepherd's Dream (1798) inspired by John Milton's Paradise Lost,[8][9] and Richard III Visited by Ghosts (1798) based on Shakespeare's play.[10] Fuseli's knowledge of art history was broad, allowing critics to propose sources for the painting's elements in antique, classical, and Renaissance art. According to the art critic Nicholas Powell, the woman's pose may derive from the Vatican's Ariadne, and the style of the incubus from figures at Selinunte, an archaeological site in Sicily.[5] A source for the woman in Giulio Romano's The Dream of Hecuba at the Palazzo del Te has also been proposed.[11] Powell links the horse to a woodcut by the German Renaissance artist Hans Baldung or to the marble Horse Tamers on Quirinal Hill, Rome.[3][11] Fuseli may have added the horse as an afterthought, since a preliminary chalk sketch did not include it. Its presence in the painting has been viewed as a visual pun on the word "nightmare" and a self-conscious reference to folklore—the horse destabilises the painting's conceit and contributes to its Gothic tone.[2]o Exhibition The painting was first shown in 1782 at the Royal Academy of London after which it became widely known.[12] Fuseli painted other versions; the original was sold for twenty guineas, while an engraving by Thomas Burke circulated widely from January 1783, earned the publisher John Raphael Smith more than 500 pounds.[12] Interpretation Both the English word nightmare[13] and its German equivalent Albtraum (literally 'elf dream') evoke a malevolent being that causes bad dreams by sitting on the chest of the sleeper.[14] Contemporary writers and critics focused on the painting's then scandalous sexual themes.[15] A few years earlier, Fuseli had fallen for Anna Landholdt in Zürich. She was the niece of his friend the Swiss physiognomist Johann Kaspar Lavater. Fuseli wrote of his fantasies to Lavater in 1779: "Last night I had her in bed with me—tossed my bedclothes hugger-mugger—wound my hot and tight-clasped hands about her—fused her body and soul together with my own—poured into her my spirit, breath and strength. Anyone who touches her now commits adultery and incest! She is mine, and I am hers. And have her I will.…"[16] Fuseli's marriage proposal met with disapproval from Landholdt's father and seems to have been unrequited—she married a family friend soon after. The Nightmare, then, can be seen as a personal portrayal of the erotic aspects of love lost. Art historian H. W. Janson suggests that the sleeping woman represents Landholdt and that the demon is Fuseli himself. Bolstering this claim is an unfinished portrait of a girl on the back of the painting's canvas, which may portray Landholdt. Anthropologist Charles Stewart characterises the sleeping woman as "voluptuous,"[15] and one scholar of the Gothic describes her as lying in a "sexually receptive position."[17] In Woman as Sex Object (1972), Marcia Allentuck argued that the intent is to show female orgasm. This is supported by Fuseli's sexually overt and even pornographic private drawings (e.g. Symplegma of Man with Two Women, 1770–78),[5] while The Nightmare has been considered representative of sublimated sexual instincts.[3] Other interpretations view the incubus as a dream symbol of male libido, with the sexual act represented by the horse's intrusion through the curtain.[18]  The Royal Academy exhibition brought Fuseli and his painting enduring fame. The exhibition included Shakespeare-themed works by Fuseli, which won him a commission to produce eight paintings for publisher John Boydell's Shakespeare Gallery.[18] One version of The Nightmare hung in the home of Fuseli's close friend and publisher Joseph Johnson, gracing his weekly dinners for London thinkers and writers.[19] Fuseli painted other versions of which at least three survive. The most important version was completed between 1790 and 1791 and is in the Goethe Museum in Frankfurt.[20] It is smaller than the original, and the woman's head lies to the left; a mirror opposes her on the right. The demon is looking at the woman rather than out of the picture, and it has pointed and catlike ears. The most significant difference in the remaining two versions is an erotic statuette of a couple on the table.[21] InfluenceVisual artsThe Nightmare was widely copied, with parodies commonly used for political caricature, including examples by George Cruikshank, Thomas Rowlandson. In these scenes, the incubus afflicts well known subjects such as Napoleon Bonaparte, Louis XVIII, British politician Charles James Fox, and Prime Minister William Pitt. In another example admiral Lord Nelson is the demon and his mistress Emma, Lady Hamilton is the sleeper.[21] While some observers have viewed the parodies as mocking Fuseli, it is more likely that The Nightmare was simply a vehicle for ridicule of the caricatured subject.[22] The Danish painter, Nicolai Abildgaard, whom Fuseli had met in Rome, produced an 1800 version of The Nightmare which develops on the eroticism of Fuseli's work. Abildgaard's painting shows two naked women asleep in the bed; it is the woman in the foreground who is experiencing the nightmare and the incubus—which is crouched on the woman's stomach, facing her parted legs—has its tail nestling between her exposed breasts.[23]

LiteratureThe Nightmare likely influenced Mary Shelley in a scene from her 1818 Gothic novel Frankenstein. Shelley would have been familiar with the painting; her parents, Mary Wollstonecraft and William Godwin, knew Fuseli. The iconic imagery associated with the Creature's murder of the protagonist Victor's wife seems to draw from the canvas: "She was there, lifeless and inanimate, thrown across the bed, her head hanging down, and her pale and distorted features half covered by hair."[16] The novel and Fuseli's biography share a parallel theme: just as Fuseli's incubus is infused with the artist's emotions in seeing Landholdt marry another man, Shelley's monster promises to get revenge on Victor on the night of his wedding. Like Frankenstein's monster, Fuseli's demon symbolically seeks to forestall a marriage.[16] Edgar Allan Poe may have evoked The Nightmare in his 1839 short story "The Fall of the House of Usher".[24] His narrator compares a painting in Usher's house to a Fuseli work, and reveals that an "irrepressible tremor gradually pervaded my frame; and, at length, there sat upon my heart an incubus of utterly causeless alarm".[25] Poe and Fuseli shared an interest in the subconscious; Fuseli is often quoted as saying that "one of the most unexplored regions of art are dreams".[25] The painting reverberated with twentieth-century psychological theorists. In 1926, the American writer Max Eastman visited Sigmund Freud and saw a print of the painting next to Rembrandt's The Anatomy Lesson in Freud's apartment in Vienna. The Freud biographer Ernest Jones chose another version of Fuseli's painting as the frontispiece of his book On the Nightmare (1931); however, neither Freud nor Jones mentioned these paintings in their writings about dreams. Carl Jung included The Nightmare and other of Fuseli works in his Man and His Symbols (1964).[26] References

Sources

Further reading

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to The Nightmare by Johann Heinrich Füssli.

|

||||||||||||||

Portal di Ensiklopedia Dunia