|

Sinking Creek Raid

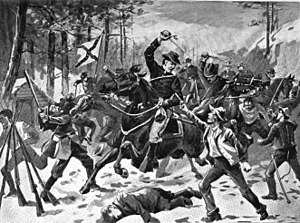

The Sinking Creek Raid took place in Greenbrier County, Virginia (now West Virginia) during the American Civil War. On November 26, 1862, an entire Confederate army camp was captured by 22 men from a Union cavalry during a winter snow storm. The 22 men were the advance guard for the 2nd Loyal Virginia Volunteer Cavalry, which was several miles behind. This cavalry unit was renamed 2nd West Virginia Volunteer Cavalry in 1863, after West Virginia became a state. The Confederates, who were the rebels in the American Civil War, had an army camp near the foot of a mountain in Sinking Creek Valley. Their camp contained about 500 soldiers, who were surprised by the small group of Union cavalry men. Many of the rebels did not have their weapons loaded. The Union cavalry raced into the camp with sabers drawn, and quickly convinced the rebels to surrender in exchange for their lives. Over 100 rebel soldiers were taken prisoner. More than 100 horses and about 200 rifles were also captured, in addition to supplies and tents. The leaders of the raid, Major William H. Powell and 2nd Lieutenant Jeremiah Davidson, both received promotions shortly afterwards. Powell was later awarded the Medal of Honor for this action. General George R. Crook said the Sinking Creek Raid was "one of the most daring, brilliant and successful of the whole war". Powell would eventually become a general. Davidson would rise to the rank of captain in the cavalry, and major in the infantry. BackgroundDuring September 1862, the Union army was forced to retreat from Western Virginia (the Kanawha River Valley) to Ohio by the Confederate army. This retreat was "embarrassing to the government".[1] The army's commander, Colonel Joseph Andrew Jackson Lightburn, was replaced by General Jacob Dolson Cox, who reorganized the troops.[2] During late October, Cox and the troops advanced to the Kanawha River Valley against no resistance. They made winter quarters in Charleston, as it was easier to be resupplied because of the river.[3] Among the Union troops was a cavalry regiment known as the 2nd Regiment of Loyal Virginia Volunteer Cavalry. This regiment was organized a year earlier, and consisted mostly of volunteers from Ohio counties near the Ohio River.[4] Its commander was Colonel John C. Paxton.[5] The regiment's quarters for the winter was at Camp Piatt, Virginia, about 12 miles (19.3 km) southeast of Charleston on the Kanawha River. The camp had a strategic location at the intersection of the Kanawha River, the James River, and the Kanawha Turnpike.[6] The Kanawha River and Kanawha Turnpike were water and land routes to the Ohio River. Union troops and supplies were often moved by steamboat up the Kanawha River to Charleston and Camp Piatt.[7] Charleston also had strategic value since a salt works was located nearby.[8] The 2nd Virginia Cavalry was glad to be back at winter quarters in Camp Piatt, Virginia, and believed they had completed their work for the year.[9] On November 22, Colonel Paxton received a surprising order from the new division commander, recently promoted Brigadier General George Crook.

Thus, Paxton would lead cavalry and infantry in an attack on two rebel camps. One rebel camp was located in Sinking Creek Valley, and the other was 2 mi (3.2 km) west of the valley near Williamsburg.[10] Before the regiment departed, General Crook confidentially told Major William H. Powell not to return to camp without good results.[11] To Cold Knob Mountain Paxton's cavalry regiment departed on November 24, traveling over 60 mi (96.6 km) towards Summersville—using less-explored roads to remain concealed.[Note 1] All companies were included except B and C, and this totaled to about 475 men.[13] Their rendezvous point with the infantry was on Cold Knob Mountain. This mountain is one of the taller mountains in today's West Virginia, with an elevation of 4,183 feet (1,275.0 m).[14] The following day, the regiment traveled another 20 mi (32.2 km) in very cold weather before searching for a suitable place to make camp. Lieutenant Jeremiah Davidson of the advance guard was in charge of selecting a camp site. Proceeding with a guide far ahead of the advance guard, he suddenly found himself surrounded by five rebels. Davidson deceived the rebels, saying he was scouting for a campsite for Colonel Albert G. Jenkins' (rebel) cavalry. He also said that he got his blue uniform from a "Yankee". Satisfied, the rebels let Davidson proceed. Shortly thereafter, the rebels saw the rest of the advance guard of the 2nd Virginia Cavalry, and fled into the woods. The rebels were all captured, including a lieutenant captured by Major Powell.[12] The regiment continued to the top of the mountain in extreme cold. A snow storm began that night (possibly earlier), and it was still snowing on the morning of the 26th.[Note 2] Colonel Philander P. Lane was the commander of the 11th Ohio Infantry.[Note 3] His regiment departed from its Summerville camp on November 24 with 500 men. The infantry's departure point and route were different from Paxton's cavalry. Lane's infantry marched through a rain storm on November 25, and reached the top of Cold Knob Mountain that evening—where there was a snow storm. Lane's report mentions frozen equipment and estimated that about 7 inches (17.8 cm) of snow was on the ground.[13] Paxton's cavalry met with Lane's infantry at a point on Cold Knob Mountain around noon on November 26. The two colonels conferred, and Lane decided that his regiment was not in condition to continue the mission. His men were wet and cold, and they began their return to their camp in Summerville.[Note 4] Paxton also considered ending the mission, but decided to continue after being convinced by Major Powell.[11] Powell was assigned to lead the advance guard, and selected Lieutenant Jeremiah Davidson and 20 men from Company G to join him. The advance guard, followed by the rest of the cavalry regiment, proceeded down the mountain toward the rebel camps.[11] Raid As the Union cavalry's advance guard rounded a sharp turn, it encountered four rebel scouts, and captured two of them. From the two prisoners, Major Powell's group was able to learn the location and strength of the two rebel camps.[11] The two escaped rebels were not strongly pursued, and did not see the entire advance guard. They assumed they had encountered a small group of Union home guard, and had no concerns as they returned to a very quiet camp of about 500 men.[18] Observing that the two rebels returning to camp were not challenged by guards, Powell and his 21 men decided to capture the entire camp—despite the remaining portion of the regiment being too far away to offer immediate support.[5] Each man in Powell's group was armed with a saber and two 54–caliber Navy Colt revolvers—meaning the group had over 200 shots before needing to reload.[Note 5] A decision was made to avoid shooting if possible—so the second rebel camp, which was located about 2 mi (3.2 km) away, would not be alarmed.[18] Powell and his men charged down the valley, a distance of about 0.5 mi (0.8 km), to the middle of the rebel cavalry camp. Many of the surprised rebels did not even have their weapons loaded. Some of the rebels tried to accost the Union cavalry by grabbing their legs, but were met with the butt of a Colt revolver or a saber.[18] Powell demanded a surrender in exchange for sparing the lives of the rebels, and this was accepted. Thus, Powell, Davidson, and 20 men captured a camp of 500 Confederate cavalry men without firing a weapon, on November 26.[20][Note 6] AftermathMany of the surprised rebels fled, and pursuit was difficult because of the terrain.[22] Colonel Paxton and the regiment did not arrive in time for the rebel surrender, but the sight of the Union regiment prevented the other Confederate cavalry camp from attacking.[20] A second objective of the mission after "breaking up" the rebel camps was to continue to Covington to rescue a Union sympathizer held by the Confederates. However, the cavalry was forced to return to its home camp because of the large number of prisoners and captured horses in its possession.[13] Colonel Paxton's report said that 2 rebels were killed, 2 were wounded, and 1 was paroled. Two officers (1 captain and 1 lieutenant) were captured. Non-commissioned officers and privates taken prisoner totaled to 111. Also captured were 106 horses and 5 mules. About 200 Enfield and Mississippi rifles were destroyed, as were 50 sabers. Additional supplies and tents were also destroyed. Union casualties were two horses killed.[23] Return to camp Moving with the prisoners (most of them on captured horses), the cavalry began its return to its home camp at 4:00 pm on November 26.[24] A concern for the regiment in addition to the rebel cavalry at the second camp was the cavalry of Colonel Jenkins, which was camped at Lewisburg about 12 mi (19.3 km) southeast of the Sinking Creek camp.[20] Paxton and the main body of the regiment took charge of the prisoners, while Powell led the rear guard. Jenkins' cavalry and Powell's rear guard skirmished briefly, but Powell held the high ground and Jenkins returned to Lewisburg.[25] The exhausted force had been moving almost constantly over the last 70 hours, in severe weather. Soldiers were falling asleep, and the officers' biggest task was simply to keep the group together on a road with 1 foot (0.3 m) of snow.[24] The 2nd Virginia stopped at daybreak on November 27. Hundreds of campfires were quickly built to thaw men and horses. Men were fed coffee and bacon, while horses were fed grain.[26] After 2 hours, the regiment was in motion again. It reached Summerville (home camp for Lane's infantry) by afternoon, and rested there until the next morning (November 28).[25] The unit lost 10 horses from exhaustion during its journey home.[23] Some of the men had frozen feet, and two remained in Summerville (after having their boots cut off their feet) until they were sufficiently recovered to be able to be moved to the hospital at Camp Piatt.[27] The unit arrived at Kanawha Falls (a.k.a. Galley Bridge) around 7:00 pm on November 28. Prisoners and captured horses were given to Union General Eliakim P. Scammon, and the 2nd Virginia camped for the night. Leaving early the next morning, the regiment reached its home camp during the afternoon of November 29.[25] Promotions Following the raid, Major Powell was promoted to lieutenant colonel, and 2nd Lieutenant Davidson was promoted to 1st lieutenant.[28] Both men received more promotions during the war. Davidson was promoted to captain on January 27, 1863.[29] On May 18, Powell was promoted to colonel, and became commander of the regiment.[30] West Virginia became a state on June 22—and the 2nd Regiment of Loyal Virginia Volunteer Cavalry became known as the 2nd West Virginia Volunteer Cavalry Regiment.[31] On July 18, Powell was severely wounded in the Wytheville Raid. He became a prisoner of war until he was exchanged on January 29, 1864. He returned to command the 2nd West Virginia Cavalry on March 20.[32] During 1864, Powell, Davidson, and the 2nd West Virginia Cavalry left the western Virginia region to fight in the Shenandoah Valley. Powell commanded a brigade.[33] Captain Davidson was severely wounded in the Second Battle of Kernstown on July 24. He was thought to have been killed, but crawled to a home where civilians saved his life.[34] He rejoined the army in September, and finished his career as a major in an Ohio infantry.[29] After the Battle of Fisher's Hill, Powell became a division commander, and was promoted to brigadier general on October 19, 1864. He resigned in 1865.[35] Years after the war, he was awarded the Medal of Honor for his performance in the Sinking Creek Raid.[36] General Crook, in a letter written to Powell in 1889, said "... I have always regarded the part you took in that expedition as one of the most daring, brilliant and successful of the whole war."[5] NotesFootnotes

Citations

References

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Portal di Ensiklopedia Dunia