|

Religion in pre-colonial Philippines

Religions in pre-colonial Philippines included a variety of faiths, of which the dominant faiths were polytheist indigenous religions practiced by the more than one hundred distinct ethnic groups in the archipelago. Buddhism, Hinduism, and Islam were also present in some parts of the islands. Many of the traditions and belief systems from pre-colonial Filipino religions continue to be practiced today through the Indigenous Philippine folk religions, Folk Catholicism, Folk Hinduism, among others. The original faith of the people of the Philippines were the Indigenous Philippine folk religions. Belief systems within these distinct polytheist-animist religions were later influenced by Hinduism and Buddhism. With the arrival of Islam in the 14th century, the older religions slowly became less dominant in some small portions in the southwest. European colonial ambitions tried to influence the people through Christian ideologies via Catholicism in the 16th century. Despite the attacks initiated by Abrahamic faiths against the Philippine indigenous folk religions by way of colonization and its after-effects, many of the indigenous religious traditions survived, while many were also infused into Abrahamic religions in the form of Folk Catholicism and Folk Islam. The earliest archaeological findings believed to have religious significance are the Angono Petroglyphs, which are mostly symbolic representations and are associated with healing and sympathetic practices from the Indigenous Philippine folk religions,[1] of which the earliest examples are believed to have been used earlier than 2000 BC., during the Philippines' Neolithic age.[2] The earliest written evidence comes from the Laguna Copperplate Inscription, dated to around 900 CE, which uses the Buddhist–Hindu lunar calendar. Indigenous Philippine folk religions Indigenous Philippine folk religions, which older references classified as animist in orientation, were the primary form of religious belief practiced in the prehistoric and early historic Philippines before the arrival of foreign influences. Today, only a handful of the indigenous tribes continue to practice the old traditions. The term animism encompasses a collection of beliefs and cultural mores anchored more or less in the idea that the world is inhabited by spirits and supernatural entities, both good and bad, and that respect must be accorded to them through worship. These nature spirits later became known as "diwatas", despite keeping most of their native meanings and symbols, due to the influence of Hinduism in the region. Some worship specific deities, such as the Tagalog supreme deity, Bathala, and his children Adlaw, Mayari, and Tala, or the Visayan deity Kan-Laon. These practices coincided with ancestor worship. Tagalogs for example venerated animals like the crocodile (buaya) and often called them "nonong" (from cognate 'nuno' i.e. 'ancestor' or 'elder'). A common ancient curse among the Tagalogs is "makain ka ng buwaya" "may the crocodile eat you!" Animistic practices vary between different ethnic groups. Magic, chants and prayers are often key features. Its practitioners were highly respected (and sometimes feared) in the community, as they were healers (Mananambal), midwives (hilot), shamans, witches and warlocks (mangkukulam), tribal historians and wizened elders that provided the spiritual and traditional life of the community. In the Visayan regions, shamanistic and animistic beliefs in witchcraft and mythical creatures like aswang (vampires), duwende (dwarves), and bakonawa (a gigantic sea serpent) Similarly to Naga, may exist in some indigenous peoples alongside more mainstream Christian and Islamic faiths. Anito

Anito is a collective name for the pre-Hispanic belief system in the Philippines. It is also used to refer to spirits, including the household deities, deceased ancestors, nature-spirits, nymphs and diwatas (minor gods and demi-gods). Ancient Filipinos kept statues to represent these spirits, ask guidance and protection. Elders, ancestors and the environment were all highly respected. Although Anito survives to the present day, it has for the most part been Christianized and incorporated into Folk Catholicism. Folk healersDuring the pre-Hispanic period, babaylan were shamans and spiritual leaders and mananambal were medicine men. At the onset of the colonial era, the suppression of the babaylans and the native Filipino religion gave rise to the albularyo. By exchanging the native prayers and spells with Catholic oraciones and Christian prayers, the albularyo was able to syncretize the ancient mode of healing with the new religion. Revitalization attemptsIn search of a national culture and identity, away from those imposed by Spain during the colonial age, Filipino revolutionaries during the Philippine Revolution proposed to revive the indigenous Philippine folk religions and make them the national religion of the entire country. However, due to the war against the Spanish and, later, American colonizers, focus on the revival of the indigenous religions were sidelined to make way for war preparations against occupiers.[3] Buddhism Although no written record exists about early Buddhism in the Philippines, recent archaeological discoveries and a few scant references in the other nations' historical records can testify that Buddhism was present from the 9th century. These records mention the independent states that comprised the Philippine archipelago, rather one united country as the Philippines are organized today. Early Philippine states became tributary states of the powerful Buddhist Srivijaya empire that controlled trade in Maritime Southeast Asia from the 6th to the 13th centuries. The states' trade contacts with the empire either before or during the 9th century served as a conduit to introduce Vajrayana Buddhism to the Philippines.  In 1225, China's Zhao Rugua, a superintendent of maritime trade in Fukien province wrote the book entitled Zhu Fan Zhi (Chinese: 諸番志; lit. 'Account of the Various Barbarians') in which he described trade with a country called Ma-i on the island of Mindoro in Luzon. In it he said:

In the 12th century, Malay immigrants arrived in Palawan, where most settlements came to be ruled by Malay chieftains. They were followed by the Indonesians of the Majapahit Empire in the 13th century, and they brought with them Buddhism. Surviving Buddhist images and sculptures are primarily found in and at Tabon Cave.[6] Recent research conducted by Philip Maise has included the discovery of giant sculptures, has also discovered what he believes to be cave paintings within the burial chambers in the caves depicting the Journey to the West.[7] The Chinese annal Song Shih recorded the first appearance of a tributary mission from Butuan (Li Yui-han 李竾罕 and Jiaminan) at the Chinese Imperial Court on March 17, 1001 AD. It described Butuan as a small maritime Hindu country with a Buddhist monarchy that had regular contact with Champa and intermittent contact with China under the Rajah named Kiling.[8] The Ancient Batangueños were influenced by India as shown in the origin of most languages from Sanskrit and certain ancient potteries. A Buddhist image was reproduced in mould on a clay medallion in bas-relief from the municipality of Calatagan. According to experts, the image in the pot strongly resembles the iconographic portrayal of Buddha in Siam, India, and Nepal. The pot shows Buddha Amithaba in the tribhanga[9] pose inside an oval nimbus. Scholars also noted that there is a strong Mahayanic orientation in the image, since the Boddhisattva Avalokitesvara was also depicted.[10] Lunar observations

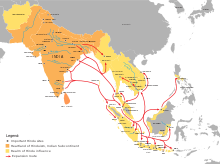

Hinduism  The archipelagoes of Southeast Asia were under the influence of Hindu Tamil, Gujarati and Indonesian traders through the ports of Malay-Indonesian islands. Indian religions, possibly an syncretic version of Hindu-Buddhism, arrived in the Philippine archipelago in the 1st millennium AD and lasted through the first half of the second millennium AD, through the Indonesian kingdom of Srivijaya followed by Majapahit. Archeological evidence suggesting exchange of ancient spiritual ideas from India to the Philippines includes the 1.79 kilogram, 21 carat golden image of Agusan (sometimes referred to as Golden Tara), found in Mindanao in 1917 after a storm and flood exposed its location.[11] The statue now sits in the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago, and is dated from the period 13th to early 14th centuries. Before the Spanish colonization of the archipelago, it was estimated that up to a third of Filipinos had Hindu beliefs, or prayed to and worshipped a Hindu god. [12]

Juan Francisco suggests that the golden Agusan statue may be a representation of goddess Sakti of the Siva-Buddha (Bhairava) tradition found in Java, in which the religious aspect of Shiva is integrated with those found in Buddhism of Java and Sumatra.[14] Folklore, arts and literatureMost fables and stories in Philippine culture are linked to Indian arts, such as the story of monkey and the turtle, the race between the deer and the snail (similar to the Western story of The Tortoise and the Hare), and the hawk and the hen. Similarly, the major epics and folk literature of the Philippines show common themes, plots, climax and ideas expressed in the Mahabharata and the Ramayana.[15] According to Indologists Juan R. Francisco and Josephine Acosta Pasricha, Hindu influences and folklore was firmly established in Philippines when the surviving inscriptions of about 9th to 10th century AD were discovered.[16] The Maranao version is the Maharadia Lawana (King Rāvaṇa of Hindu Epic Ramayana). Lam-Ang is the Ilocano version and Sarimanok (akin to the Indian Garuda) is the legendary bird of the Maranao people. In addition, many verses from the Hud-Hud of the Ifugao are derived from the Indian Hindu epics Ramayana and the Mahabharata.[17] Buddhist-Hindu influencesThe Darangen or Singkil epic of the Maranao people hearten back to this era as the most complete local version of the Ramayana. Maguindanao at this time was also strongly Hindu, evidenced by the Ladya Lawana (Rajah Ravana) epic saga that survived to the modern day, as albeit highly Islamized from the 17th century onwards. TigmamanukanThe Tigmamanukan was a blue and black bird (believed to be the Philippine Fairy Bluebird) which served as a messenger of Bathalang Maykapal, in which it was also an omen.[18] If one encountered a Tigmamanukan while traveling, they should take note of the direction of its flight. If the bird flew to the right, the traveler would not encounter any danger during their journey. If it flew to the left, the traveler would never find their way and would be lost forever. Islam The Muslim Bruneian Empire, under the rule of Sultan Bolkiah (who is an ancestor of the current Sultan of Brunei, Hassanal Bolkiah), subjugated the Kingdom of Tondo in 1500. Afterwards, an alliance was formed between the newly established Kingdom of Maynila (Selurong) and the Sultanate of Brunei and the Muslim Rajah Sulaiman was installed in power. Furthermore, Sultan Bolkiah's victory over Sulu and Seludong (modern day Manila),[19] as well as his marriages to Laila Mecanai, the daughter of Sulu Sultan Amir Ul-Ombra (an uncle of Sharifa Mahandun married to Nakhoda Angging or Maharaja Anddin of Sulu), and to the daughter of Datu Kemin, widened Brunei's influence in the Philippines.[20] Rajah Suleyman and Rajah Matanda in the south (now the Intramuros district) were installed as Muslim kings and the Buddhist-Hindu settlement was under Raja Lakandula in northern Tundun (now Tondo.)[21] Islamization of Luzon began in the sixteenth century when traders from Brunei settled in the Manila area and married locals while maintaining kinship and trade links with Brunei and thus other Muslim centres in Southeast Asia. There is no evidence that Islam had become a major political or religious force in the region, with Father Diego de Herrera recording that inhabitants in some villages were Muslim in name only.[22] Historiographic sourcesEarly foreign written recordsMost records concerning pre-colonial Philippine religion can be traced back through various written accounts from Chinese, Indian and Spanish sources.

LCIThe Laguna Copperplate Inscription (LCI) is the most significant archaeological discovery in the Philippines because it serves as the first written record of the Philippine nation. The LCI mentions a debt pardon for a person, Namwaran, and his descendants by the Rajah of Tundun (now Tondo, Manila) on the fourth day after Vaisakha, in the Saka year 822, which has been estimated to correspond to April 21, 900 CE. The LCI uses the old Buddhist-Hindu lunar calendar. Antoon Postma, an anthropologist and an expert in ancient Javanese literature, has deciphered the LCI and he says it records a combination of old Kavi, Old Tagalog, and Sanskrit.[23] Ancient artifactsThe Philippines's archaeological finds include many ancient gold artifacts.[24][25] Most of them have been dated to belong to the 9th century. The artifacts reflect the iconography of the Vajrayana Buddhism and its influences on the Philippines's early states.[26] Some of the iconography and artifacts are exampled

See alsoReferences

Sources

External links |