|

Mongrel complex

"Mongrel complex", or alternatively "mutt complex" (Portuguese: complexo de vira-lata, lit. 'street dog complex, mutt complex, trashcan-tipper complex'), is a derogatory expression, usually used by nationalists, to refer to a supposedly "collective inferiority complex" reportedly felt by many Brazilians when comparing Brazil and its culture to other parts of the world, primarily the developed world, as the reference to a mongrel carries negative connotations attributed by Brazilians to the racist perception of most Brazilians being racially mixed as well as lacking in desirable cultural refinement. The term has gained controversy in recent years due to its association to racism and ultranationalism. Some critics have accused the term of being a racial slur.[citation needed] BackgroundThe term was originally coined by novelist and writer Nelson Rodrigues, initially referring to the trauma suffered by Brazilians in 1950 when the national football team was defeated by Uruguay's national team in the final match of the 1950 World Cup, which was held at the Maracanã in Rio de Janeiro. The estimated 200,000 spectators at the stadium that day were stunned into an eerie silence after the match concluded, some so distraught they committed suicide inside the stadium.[1] Brazil would recover, at least when it comes to football, in 1958, winning the World Cup for the first of five times,[2] but the idea persisted, cropping up again the next time Brazil hosted the World Cup in 2014 when it was defeated in the semi-final match against Germany by a score of 7–1. For Rodrigues, the phenomenon was not exclusively related to sport. According to him:[3]

The expression "mongrel complex" was rediscovered in 2004 by American journalist Larry Rohter. In an article for The New York Times about the Brazilian nuclear program, he wrote:

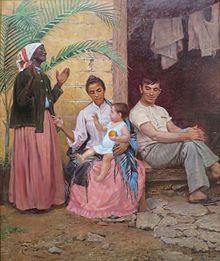

OriginsThe idea that the Brazilian people are inferior to others or "degenerate" is not novel and dates back to the 19th century, when French nobleman Arthur de Gobineau visited Rio de Janeiro in 1845 and described the city's residents as "unbelievably ugly monkeys".[5] In the 1920s and 1930, many currents of thought clashed concerning the origin of the supposed inferiority. Some, such as Nina Rodrigues, Oliveira Viana, and Monteiro Lobato proclaimed that miscegenation was the root of all evils and that the white race was superior to others. Others, such as Roquette-Pinto, claimed that the inferiority was a matter of ignorance, rather than miscegenation. In 1903, Lobato reveals himself to be profoundly pessimistic about the potential of the Brazilian people, by him thus defined:

Aside from the mixed origin, Brazilians supposedly also suffer from the fact they live in the tropics, where the hot and humid climate would predispose inhabitants to sloth and lust (another thesis that was held dear at the time, geographical determinism, alleged that the true civilizations can only develop in temperate climates). Nevertheless, when Lobato published Urupês in 1918, portraying "Jeca Tatu", the Brazilian elite was starting to favor another explanation of the "backwardness" of the country. With the publication of a series of public health studies ordered by Oswaldo Cruz, then-current poor sanitary conditions at the countryside take place as the main cause of the "lack of vigor" and the "indolence" of the Brazilians. Sanitarism becomes the trend and Lobato himself engages in the effort of converting Brazil into a "big hospital", in the words of physician Miguel Pereira. This effort peaks in 1924, when Lobato publishes "a história do Jecatatuzinho" ("the story of little Jeca Tatu"), used as an advert for Biotônico Fontoura, a traditional nutritional supplement. In the story, after being healed "by science", Jeca Tatu, the titular character, becomes a model citizen and entrepreneur, capable even of surpassing the production of his prosperous neighbor – an Italian immigrant. CriticismHowever, many Brazilian critics and writers have opposed this concept, arguing that the idea of a "complex" often ignores the nuances of cultural and artistic appreciation. Among these critics, we can highlight names such as Adélia Prado, Augusto de Campos and Hilda Hilst. Each, in their own way, presented arguments that challenge Nelson Rodrigues' view. Reasons and Arguments Against the "Mongrel Complex":

See also

References

|

Portal di Ensiklopedia Dunia