|

Blanqueamiento

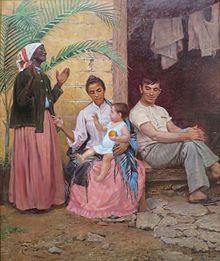

Blanqueamiento in Spanish, or branqueamento in Portuguese (both meaning whitening), is a social, political, and economic practice used in many post-colonial countries in the Americas and Oceania to "improve the race" (mejorar la raza)[1] towards a supposed ideal of whiteness.[2] The term blanqueamiento is rooted in Latin America and is used more or less synonymously with racial whitening. However, blanqueamiento can be considered in both the symbolic and biological sense.[3] Symbolically, blanqueamiento represents an ideology that emerged from legacies of European colonialism, described by Anibal Quijano's theory of coloniality of power, which caters to white dominance in social hierarchies.[4] Biologically, blanqueamiento is the process of whitening by marrying a lighter-skinned individual to produce lighter-skinned offspring.[4] Definition Peter Wade argues that blanqueamiento is a historical process that can be linked to nationalism. When thinking about nationalism, the ideologies behind it stem from national identity, which according to Wade is "a construction of the past and the future",[5] where the past is understood as being more traditional and backwards. For example, past demographics of Puerto Rico were heavily black and Indian-influenced because the country partook in the slave trade and was simultaneously home to many indigenous groups. Therefore, understanding blanqueamiento as it relates to modernization, modernization is then understood as a guidance in the direction away from black and indigenous roots. Modernization then happened as described by Wade as "the increasing integration of blacks and Indians into modern society, where they will mix in and eventually disappear, taking their primitive culture with them".[5] This kind of implementation of blanqueamiento takes place in societies that have historically always been led by 'white' people whose guidance would carry "the country away from its past, which began in Indianness and slavery"[5] with hopes of promoting the intermixing of bodies to develop a predominantly white-skinned society. As related to mestizajeThe formation of mestizaje emerged in the shift of Latin America towards multiculturalist perspectives and policies.[6] Mestizaje has been considered problematic by many scholars because it sustains racial hierarchies and celebrates blanqueamiento.[6] For example, Swanson argues that although mestizaje is not a physical embodiment of whitening, it is "not so much about mixing, as it about a progressive whitening of the population".[7] Another possibility when considering mestizaje as it relates to blanqueamiento is by understanding mestizaje as a concept that encourages mixedness, but differs from the concept of blanqueamiento on the basis of the end goal for mestizaje. As Peter Wade states, "it celebrates the idea of difference in a democratic, non-hierarchical form. Rather than envisioning a gradual whitening, it holds up the general image of the mestizo in which racial, regional, and even class differences are submerged into a common identification with mixedness."[5] On the same coin, when thinking about blanqueamiento, the future goal takes up the same theme of mixing. The difference between them is that while mestizaje glorifies the mixing of all people to reach an end goal of having a brown population, blanqueamiento has the end goal of whiteness. The outcome of mestizaje mixing would lead to "the predominance of the mestizo" and is not "construed necessarily as (a) whitened mestizo".[5] Most importantly, both of these ideologies link emerging nationhood with the predominance of the mestizo or the whitened population. In the early Republican era of Brazil, miscegenation as a form of whitening was looked down upon, as it was thought that the mestiço population retained the inferior qualities of the Indigenous and Afro-Brazilians.[8] It was for this reason that immigration as a form of whitening was preferred rather than through interracial relations. Theorists such as Raimundo Nina Rodrigues believed that education could improve the state of certain groups, such as Muslim Africans, however Indigenous and Afro-Brazilians were excluded from this.[8] National policyBlanqueamiento was enacted in national policies of many Latin American countries at the turn of the 20th century. In most cases, these policies promoted European immigration as a means to whiten the population.[9] BrazilBranqueamento was circulated in national policy throughout Brazil in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.[10][11] Branqueamento policies emerged in the aftermath of the abolition of slavery and the beginning of Brazil's first republic (1888–1889). To dilute the black race, the Brazilian government took measures to increase European immigration.[10][12] More than 1 million Europeans arrived in São Paulo between 1890 and 1914.[13] State and federal governments funded and subsidized immigrant travels[12] from Portugal, Spain, Italy, Russia, Germany, Austria, France, and the Netherlands.[14] Claims that white blood would eventually eliminate black blood were found in accounts of immigration statistics.[14] Created in the late 19th century, Brazil's Directoria Geral de Estatística (DGE) has conducted demographic censuses and managed to measure the progress of whitening as successful in Brazil.[14] CubaAt the beginning of the 20th century, the Cuban government created immigration laws that invested more than $1 million into recruiting Europeans into Cuba to whiten the state.[15] High participation of blacks in independence movements threatened white elitist power and when the 1899 census showed that more than 1⁄3 of Cuba's population was colored, white migration started to gain support.[16] Political blanqueamiento began in 1902 after the U.S. occupation, where migration of "undesirables" (i.e. blacks) became prohibited in Cuba.[17] Immigration policies supported the migration of entire families. Between 1902 and 1907, nearly 128,000 Spaniards entered Cuba, and officially in 1906, Cuba created its immigration law that funded white migrants.[17] However, many European immigrants did not stay in Cuba and came solely for the sugar harvest, returning to their homes during the off seasons. Although some 780,000 Spaniards migrated between 1902–1931, only 250,000 stayed. By the 1920s, blanqueamiento through national policy had effectively failed.[16] SocialBlanqueamiento is also associated with food consumption. For example, in Osorno, a Chilean city with a strong German heritage, consumption of desserts, marmalades and kuchens "whitens" the inhabitants of the city.[18] EconomicBlanqueamiento can also be accomplished through economic achievement. Many scholars have argued that money has the ability to whiten, where wealthier individuals are more likely to be classified as white, regardless of phenotypic appearance.[5][19][20] It is by this changing of social status that blacks achieve blanqueamiento.[21] In his study, Marcus Eugenio Oliveira Lima showed that groups of Brazilians succeeded more when whitened.[13] Blanqueamiento has also been seen as a way to better the economy. In the case of Brazil, immigration policies that would help whiten the nation were seen as progressive ways to modernize and achieve capitalism.[12] In Cuba, blanqueamiento policies limited economic opportunities for African descendants, resulting in their reduced upward mobility in education, property, and employment sectors.[17] See also

References

|