|

Karst dialect

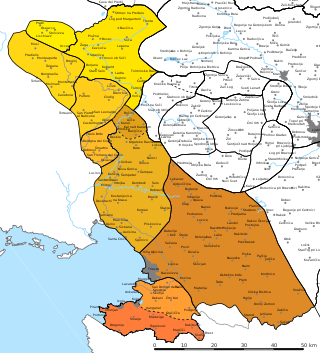

The Karst dialect (Slovene: kraško narečje [ˈkɾáːʃkɔ naˈɾéːt͡ʃjɛ],[1] kraščina[2]), sometimes called the Gorizia–Karst dialect (Slovene: goriškokraško narečje [gɔˈɾìːʃkɔˈkɾáːʃkɔ naˈɾéːt͡ʃjɛ]),[3] is a Slovene dialect spoken on the northern Karst Plateau, in the central Slovene Littoral, and in parts of the Italian provinces of Trieste and Gorizia. The dialect borders the Inner Carniolan dialect to the south, the Cerkno dialect to the east, the Tolmin dialect to the northeast, the Soča dialect to the north, the Natisone Valley and Brda dialects to the northwest,[4] and Venetian and Friulian to the west. The dialect belongs to the Littoral dialect group, and it evolved from the Venetian–Karst dialect base.[4][5] Geographic distributionThe name of the dialect is somewhat misleading because its use is not limited to the Karst Plateau, nor does it encompass the entire Karst Plateau. It is spoken only in the northwestern parts of the Karst Plateau, in a line from the villages of Prosecco (Slovene: Prosek) and Contovello (Kontovel) near Trieste, west of Sgonico (Zgonik), Dutovlje, Štanjel, and Dobravlje. East of that line, the Inner Carniolan dialect is spoken. In addition to the northwestern part of the Karst Plateau, the dialect is spoken in the lower Vipava Valley (west of Črniče), in the lower Soča Valley (south of Ročinj and up to Manizza, Majnica), and on the Banjšice Plateau and the Trnovo Forest Plateau. It thus encompasses most of the territory of the Municipality of Kanal ob Soči, and the entire territory of the municipalities of Nova Gorica, Renče-Vogrsko, Šempeter-Vrtojba, Miren-Kostanjevica, and Komen, as well as some villages in the western part of the Municipality of Sežana. It is also spoken in the southern suburbs of the Italian town of Gorizia (Gorica, most notably in the suburb of Sant'Andrea, Štandrež), and in the municipalities of Savogna d'Isonzo (Sovodnje), Doberdò del Lago (Doberdob), and Duino-Aurisina (Devin-Nabrežina). It is also spoken in some northwestern suburbs of Trieste, especially in Barcola (Barkovlje), Prosecco, and Contovello.[6][4] Notable settlements include Prosecco (Prosek), Santa Croce (Križ), Aurisina (Nabrežina), Sistiana (Sesljan), Duino (Devin), Savogna (Sovodnje), Lucinico (Ločnik), and Gorizia (Gorica) in Italy, as well as Komen, Branik, Dornberk, Prvačina, Renče, Vogrsko, Miren, Bilje, Bukovica, Volčja Draga, Šempeter, Vrtojba, Šempas, Vitovlje, Ozeljan, Nova Gorica, Solkan, Grgar, Deskle, Anhovo, and Kanal ob Soči in Slovenia. Some 60,000 to 70,000 Slovene speakers live in the territory where the dialect is spoken, most of whom have some level of knowledge of the dialect. Accentual changesThe Karst dialect has lost pitch accent, as well as the distinction between long and short vowels. It has also undergone four accent shifts: *ženȁ → *žèna, *məglȁ → *mə̀gla, *visȍk → vìsok, and *ropotȁt → *ròpotat. The Banjšice subdialect still distinguishes between long and short vowels and has not undergone the *ropotȁt → *ròpotat shift.[7] PhonologyNon-final *ě̀ and *ě̄ turned into iːẹ or iːə. Alpine Slavic and later lengthened *ę̄ turned into iːe or iːə, around Gorizia to aː, and ə or ḁ from Vrtovin to Solkan and Grgar. The vowel *ē turned into iːẹ or iːə. The vowel *ō turned into uː under influence from the Inner Carniolan dialect southeast of Komen; elsewhere it is uːọ or uːə, whereas non-final *ò remained a diphthong everywhere. Alpine Slavic *ǭ and non-final *ǫ̀ turned into uːo, uːə, or uọ, or simplified to uː around Dutovlje and Komen. The vowel *ū evolved into uː. Syllabic *ł̥̄ mostly turned into uː, probably because of Bosnian immigrants, but some microdialects still pronounce it as oːu̯.[8] Long *ə̄ turned into aː, and around Solkan back into ə.[9] Final *ǫ, *o, *ę, and *e turned into u, o, ə, and e, respectively.[8] Palatal consonants are still palatal, except that *t’ turned into ć, rarely also into č, and *ĺ might have depalatalized. The consonant *g turned into ɣ. Velar *ł still exists.[10] The Banjšice subdialect is more archaic; diphthongs are more prominent, *ǭ turned into oː, and *ę̄ mostly turned into aː, although eː and ieː also exist. The vowel *ē mostly turned into *eː, but it is still ieː in the south. Newly stressed e and o are pronounced as short e̥/ə and ọ (in the far north also a), respectively. Palatal *ń turned into i̯n in Avče.[11] MorphologyNeuter gender exists in the singular, but it has been feminized in the plural. The dual has mostly been lost, except in the east, where there are some remnants. All verbs have an -s- infix in the second- and third-person plural.[12] The long infinitive has been replaced by the short infinitive,[6] and o-stem nouns have the ending -i in the dative and locative singular.[12] SubdivisionThe Karst dialect has a more archaic subdialect, the Banjšice subdialect, in the northern part, which still has length oppositions in stressed syllables and has not undergone the *ropotȁt → *ròpotat accent shift.[5] Northern microdialects (particularly the Avče microdialect) show the influence of the Tolmin dialect.[11] The rest of the Karst dialect is not uniform either, and it can mainly be split into four subcategories, based on the pronunciation of *ǭ and *ę̄. The vowel *ǭ is pronounced as uːo/uːə in the west and u in the east, and *ę̄ is pronounced as ieː~aː in the north and as ieː in the south.[5] References

Bibliography

|

||||||||||||||||||||||