|

Geneva Medical College

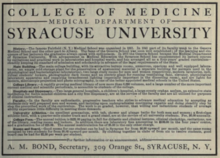

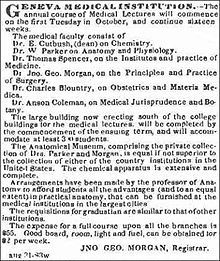

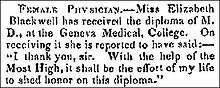

Geneva Medical College was founded on September 15, 1834, in Geneva, New York, as a separate department (college) of Geneva College, currently known as Hobart and William Smith Colleges.[2] In 1871, the medical school was transferred to Syracuse University in Syracuse, New York.[2] In 1950, State University of New York (SUNY) moved to add a medical center in Syracuse and ultimately acquired the College of Medicine from Syracuse University as a part of Governor Thomas E. Dewey's vision for Upstate New York.[3] For many years the college was known as "SUNY Upstate Medical Center," until 1986, when the name was changed to "SUNY Health Science Center at Syracuse". The institution was renamed to State University of New York Upstate Medical University in 1999. On December 22, 2021, the College of Medicine was renamed the Alan and Marlene Norton College of Medicine at SUNY Upstate in recognition of a $25 million estate gift made by Alan and Marlene Norton.[4][5] Alan Norton graduated from the College of Medicine in 1966 and then went on to complete his residency and fellowship training at the Wilmer Eye Institute of Johns Hopkins University and Massachusetts Eye and Ear. FoundingThe medical school was founded in 1834 by Edward Cutbush, a physician and naval surgeon who also served as the first dean for the college and professor of chemistry.[2] He was an officer in the U.S. Navy for thirty years (from 1799 to 1829) and has been called the father of American naval medicine.[6] Cutbush was the founder and first President of the Columbian Institute for the Promotion of Arts and Sciences in Washington in 1816. John Quincy Adams was President of the institute by 1825.[7] Cutbush attended a dinner, hosted by the institute in early January 1825, where he spoke about science and discussed his hope for the future of education in the United States; "May the resources and prosperity of our country be increased by its application to agriculture, commerce, the arts, and manufactures."[7] The medical school opened its doors on February 10, 1835, and later that year the first six physicians graduated.[2] HistoryThe earliest roots of the college extend back to the 1792 establishment in New Jersey of Queens Medical College, which later became Rutgers Medical College,[8] albeit, the importance of the relation to Geneva Medical College is disputed by some.[9] Rutgers Medical College of Rutgers CollegeIn 1826, David Hosack of New York City suggested an alliance with Rutgers College, located in New Brunswick, New Jersey, favored because of its proximity to New York.[10] Hosack and Nicholas Romayne sought academic sponsorship for their medical schools. They were early proponents in the belief that medical education should be easily accessible.[10] Hosack was Alexander Hamilton's personal physician and was with him during his duel with Aaron Burr on July 11, 1804.[11] Not long after the alliance with Rutgers began, he found himself the target of the New York State Board of Regents, over complaints of excessive fees charged to students. Hosack and four colleagues resigned.[10] "The flamboyant personalities (involved) and notoriety attracted students and money away from competing schools and drew animosity to them like a magnet. The story of the intrigues and political in-fighting of New York City's physicians, their medical societies and institutions during this time period is a complex one."[8] Much political maneuvering resulted, ultimately involving the New York State Supreme Court.[8] Hosack and his associates turned to the board of trustees of Rutgers College on October 16, 1826, and requested a "connection" by which the petitioners would become the medical faculty of the college.[10] Instruction began on November 6, 1826, in New Brunswick Immediate opposition to Hosack and Rutgers Medical School surfaced, and he came under attack by the County Medical Society of New York for "unjustifiable interference in the medical concerns of the state and disregard for the provisions of the laws of the state regarding medical education."[8] Rutgers countered with attacks against the College of Physicians and Surgeons and its supporters for "perpetuating monopoly in medical education."[8] Two years of acrimonious debate ended with Hosack's opponents successfully enacting a bill that negated any medical degrees "as licenses to practice medicine in New York State" granted outside of the City of New York. This move effectively ended the New Brunswick connection.[10] Rutgers Medical Faculty of Geneva CollegeUndaunted, Hosack traveled to Upstate New York and succeeded in gaining the sponsorship of Geneva College in Geneva, New York.[9] Soon after, the Rutgers Medical College established under the authority of Rutgers College, New Jersey, transferred its allegiance to Geneva College in the State of New York.[12] The trustees of the college voted on October 30, 1827, to establish the medical faculty.[9] According to the trustees' minutes, the Geneva College was to consist of two branches, one in Geneva and the other in New York City. Each branch would have six professors. The medical school in Geneva never materialized, due to one delay after another, and the venture was abandoned.[9] The second branch was established in New York City under the direction of Dr. Hosack and was known as the Rutgers Medical Faculty of Geneva College. The doors were opened in early November 1827; "amid a barrage of criticism on the part of the New York College of Physicians and Surgeons."[9] This affiliation lasted from 1827 to 1830 when Hosack's adversaries filed suit in "The People v. The Trustees of Geneva College" which ruled that the college did not have the power to operate or appoint a faculty at any place but Geneva. This invalidated the branch in New York City.[10] Forced by enactments of the New York State Legislature by the New York Supreme Court, Geneva College severed its relationship with Rutgers on November 1, 1830,[11] although the school continued operations in New York City under the name Rutgers Medical College until 1835. At that time, the fruitlessness of awarding only "honorary" degrees was realized.[8] Geneva College, as revealed in the trustees' minutes, quietly accepted the decision of the court. The Geneva College, Rutgers Medical Faculty had ceased to exist.[9] Fairfield Medical College It is also believed that a similar relationship existed (as Rutgers Medical Faculty enjoyed with Geneva College) to "The College of Physicians and Surgeons of the Western District of New York" which was located in Fairfield, New York. The school was chartered in 1812.[13] The relationship to this institution is not fully known, however, the first medical instructors at Geneva College were connected with the medical school at Fairfield.[8] The relationship with Fairfield College is concerned with the formation of Geneva College in 1821 when Trinity Church bequeathed a grant of $750 per annum to Geneva College, specifically for the support of an academy at Fairfield.[14] "During its early life, the Fairfield Medical College had benefited from a corporate connection with the Geneva Academy which numbered among its friends and patrons the influential and wealthy Trinity Episcopal Church of New York City"[9] It was noted that the main interest of the church was creating a theological school for training men for the priesthood of the Episcopal Church. With the founding of Episcopal College at Geneva, New York, in 1825, the support of Fairfield by Trinity Church came to an end.[9] According to Polk's Medical Register published in 1914, the Fairfield Medical College merged "part into the Albany Medical College and part into Geneva Medical College in 1841"[13] and the school officially closed its doors.[9] During its existence it instructed a total of 3,123 students and graduated 596 as physicians.[13] Medical Institution of Geneva College In September 1834, by action of the board of trustees,[15] the "Medical Institution of Geneva College" was chartered and the school began operation on February 10, 1835.[9] It has also been referred to as the Geneva Medical Faculty.[9] Whether the early connection to Rutgers Medical Faculty of Geneva College, located in New York City, had any role in the formation of the Geneva Medical Faculty, has been debated.[9] However, it has already been noted that Rutgers did make use of the Geneva College name in their official corporate title for a period of three years.[8] Additionally, it did appear that the trustees of Geneva College began a discussion concerning the formation of a medical school at Geneva not long after the Rutgers ties were broken. "The memory of the New York branch persisted at Geneva, and it was not long before voices were raised advocating the establishment of a local medical college."[9] The trustees of Geneva College stated their intentions that new buildings for the Academic Department would be erected and the "present" college building would be used for the Medical Department and "until this is done, convenient rooms in other buildings will be provided for the accommodation of the Medical lectures."[15] The Medical faculty of the institution announced that the Lecture Term would commence annually on the second Tuesday of February and continue sixteen weeks. The Medical Commencement would be held on the Tuesday following the closing of the lectures. The aggregate fee for the lecture tickets was $55 and each ticket was required to be paid for at the time it was received. For any student attending the full lecture, the price could not exceed $100 for two years of study.[15] The trustees discussed how students could obtain board in good families in the Geneva area from $1.50 to $2.00 per week.[15] The graduation fee was $20. All fees collected were appropriated for "the purchase of a Medical Library and Anatomical Museum."[15] In order to be eligible for the degree Doctor of Medicine; "He shall have attained the age of twenty one years, and be of good moral character; he must have attended two full courses of Lectures, one of which must have been in this Institution and have studied three years under some respectable practitioner of Medicine, and have an adequate knowledge of the Latin language and of Natural Philosophy. He must likewise write and present to the Dean of the Faculty a Thesis on some medical subject, to be approved, and must pass a satisfactory examination by the Medical Faculty in the presence of the Curators of this Institution."[15] By 1836, a building was erected for the use of the medical faculty. In 1841, a new medical building was erected on the east side of Main Street in Geneva. The medical faculty building (middle building) was then devoted to the use of the literary department. The state contributed $15,000 towards the fund for the erection of the new medical building.[16] Unfortunately, the medical building was destroyed by fire in 1877; however, long after the college had discontinued use of the facility as a medical school.[16]  First woman in medicine In 1847, Elizabeth Blackwell was admitted to the Medical Institution of Geneva College. She had applied to and was rejected, or simply ignored, by 29 medical schools before her acceptance at Geneva.[17] The medical faculty, largely opposed to her admission but seemingly unwilling to take responsibility for the decision, decided to submit the matter to a vote of the 150 male students.[17] The men of the college, perhaps as a practical joke on the faculty, or thinking it was a prank, voted to admit her.[18] Blackwell graduated two years later, on January 23, 1849, at the head of her class, the first woman in the history of education in the United States to receive a doctor's degree in medicine.[19] "The occasion marked the culmination of years of trial and disappointment for Miss Blackwell, and was a key event in the struggle for the emancipation of women in the nineteenth century in America."[20] Soon after, Blackwell was celebrated as the first licensed woman physician in the United States. Within three years, another 20 women throughout the country had graduated from medical school.[17] Blackwell went on to found the New York Infirmary for Women and Children and had a role in the creation of its medical college.[19] Geneva Medical College of Hobart CollegeGeneva Medical College's parent school was known as Geneva College until 1852, when it was renamed in memory of its most forceful advocate and founder, Episcopal bishop John Henry Hobart, to Hobart Free College. In 1860, the name was shortened to Hobart College and is currently known as Hobart and William Smith Colleges.[21] That same year, things took a turn for the worse. The recent establishment of medical school at the University of Buffalo in 1846 took a hefty toll on the number of students enrolled at Geneva.[9] The situation was so serious that, Dr. Sumner Rhoades, one time member of the faculty, published an open letter in the Geneva Gazette advocating the dissolution of the medical faculty. In its place, Dr. Rhoades favored the founding of an agricultural college.[9] Bishop DeLancey of the Episcopal Church was against the plan, but when the faculty gathered in the fall of 1853, they discovered that no students had registered in medicine. The faculty resigned, and for a year there was no instruction in medicine offered. In 1854, a new faculty was organized; however; enrollment soon fell to below a hundred per year (from a high of almost 200 in the late 1840s). By the close of the 1850s, the number had dropped to 22. During this time, the college was floundering on expenses, but they managed to carry on and keep the department alive.[9] Finally, in January, 1869, the trustees of Hobart College debated the question of abolishing the Medical Faculty. A local campaign was organized and raised an endowment for Hobart College that managed to yield $10,000 for the school. The amount was by no means sufficient to cover the costs of the college. On July 12, 1871, the trustees of Hobart voted that the "'Medical Department' of the College be discontinued after the first of February, 1872."[9] At that time, the board of trustees recommended that the medical school be transferred to Syracuse University in Syracuse, New York. Many of the professors from Geneva agreed to transfer to Syracuse and all agreed to work without any pay for the first year.[9] Geneva Medical College existed from 1834 to 1872, and over the course of 38 years,[9] a total of 596 students were graduated.[1] College of Medicine – Syracuse University On November 15, 1871, a special meeting of the Onondaga County Medical Society took place in the county courthouse in Syracuse to confer with representatives of Geneva Medical College (of Hobart College) and Syracuse University. "The purpose of the meeting was to determine the attitude of the local medical profession to the possible transfer of the medical school to Syracuse."[21] Bishop Dr. J. T. Peck and Dr. W. W. Porter represented Syracuse University and Professors Frederick Hyde and John Towler represented the Geneva Medical College.[22] Dr. Peck presented the subject at length. He alluded to the intention of its founders to ensure the university was "comprehensive," embracing the post-graduate departments including law, theology, medicine, etc. and the original founders ideas that although they might not be established immediately, they would eventually "as funds shall be provided for the purpose."[22] It was felt that since Syracuse was a much larger city than Geneva and already had two "well-appointed" hospitals which were available for teaching and the fact the city of Syracuse offered "chemical advantages and presented necessary surgical and medical cases for practical instruction," that the university offered many advantages to the medical college.[22] "The views, in general, were that medical colleges in country towns were necessarily so destitute of large hospital and chemical opportunities as to fail to furnish the proper condition to success."[22] In addition, it was felt that Syracuse was situated a sufficient distance from any other large city, connected by numerous railroads "with the towns and country surrounding, it was the natural center of the state."[22] The city's various manufacturing and commercial interests, and its "present rapid growth," gave promise to the board that it would soon be one of the largest cities in New York.[22] After considerable discussion, a resolution was adopted by the County Medical Society approving the transfer of the medical school to Syracuse. A committee was elected to communicate the actions to the trustees of the university and to assist in the transfer and establishment of the college in Syracuse.[21] Dr. Alfred Mercer, a member of the class of 1843,[23] was chairman of the committee representing the County Medical Society in connection with the transfer of the college from Geneva. He expressed the sentiment of the medical group as follows: "What we need is not more medical schools, but fewer and better ones."[21] Temporary quarters were found for the college in the Clinton Block in Syracuse, the site of the current main post office. The first session began in the fall of 1872.[21] The dean from 1907 to 1922 was Dr. John Lorenzo Heffron, who joined the teaching staff in 1883.[24][25][26] His daughter Marian married Holworthy Hall, the novelist and short story writer H. E. Porter.[27] State University of New York Upstate Medical UniversityIn 1950, State University of New York (SUNY) moved to add a medical center in Syracuse and ultimately acquired the College of Medicine from Syracuse University as a part of Governor Thomas E. Dewey's vision for Upstate New York.[3] For many years the college was known as SUNY Upstate Medical Center, until 1986, when the name was changed to SUNY Health Science Center at Syracuse. The institution was renamed to SUNY Upstate Medical University in 1999. The State University of New York Upstate Medical University is located in the University Hill section of Syracuse. It includes the College of Medicine (COM), College of Nursing, College of Health Professions and College of Graduate Studies. Deans of the Geneva Medical CollegeThe deans of the Geneva Medical College included :[28]

FacultyThe medical faculty of the old Geneva Medical College included men "who became famous in the history of our country."[8] The Faculty of Medicine was appointed by the trustees in September 1834, and included; Dr. Edward Cutbush (professor of chemistry), Dr. Willard Parker (professor of anatomy and physiology) after whom the communicable disease center of the City of New York was named,[8] Dr. Thomas Spencer (professor of the Institutes and Practice of Medicine), Dr. John George Morgan (professor of the principles and practice of surgery), Dr. Charles Broadhead Coventry (professor of obstetrics and materia medica) and Dr. Anson Coleman (professor of medical jurisprudence and botany).[15] In 1840, several members of the faculty at Fairfield Medical College were "removed" to Geneva including Professors Dr. James Hadley (professor of chemistry and pharmacy),[29] Dr. John Delamater and Dr. Frank Hastings Hamilton (professor of the principles and practice of surgery).[9] By 1847, a few more names had been added to the medical faculty; Dr. James Webster (professor of anatomy and physiology), Dr. Charles Alfred Lee (professor of materia medica and general pathology and dean of the faculty), Dr. Austin Flint (lecturer on the institutes and practice of medicine) and Dr. Corydon La Ford (demonstrator of anatomy).[29] Several prominent doctors from Syracuse who were among early faculty members included; Dr. A. E. Larkin, Dr. Edward S. Van Duyn and Dr. Alfred Mercer and his son, Dr. A. Clifford Mercer.[30]  Portrait of Elizabeth Blackwell by Joseph Stanley Kozlowski

Notable alumnae and alumni

References

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Geneva Medical College.

|

||||||||||||||||||

Portal di Ensiklopedia Dunia