|

Faraday paradox The Faraday paradox or Faraday's paradox is any experiment in which Michael Faraday's law of electromagnetic induction appears to predict an incorrect result. The paradoxes fall into two classes:

Faraday deduced his law of induction in 1831, after inventing the first electromagnetic generator or dynamo, but was never satisfied with his own explanation of the paradox. Faraday's law compared to the Maxwell–Faraday equationFaraday's law (also known as the Faraday–Lenz law) states that the electromotive force (EMF) is given by the total derivative of the magnetic flux with respect to time t: where is the EMF and ΦB is the magnetic flux through a loop of wire. The direction of the electromotive force is given by Lenz's law. An often overlooked fact is that Faraday's law is based on the total derivative, not the partial derivative, of the magnetic flux.[1] This means that an EMF may be generated even if total flux through the surface is constant. To overcome this issue, special techniques may be used. See below for the section on Use of special techniques with Faraday's law. However, the most common interpretation of Faraday's law is that:

This version of Faraday's law strictly holds only when the closed circuit is a loop of infinitely thin wire,[4] and is invalid in other circumstances. It ignores the fact that Faraday's law is defined by the total, not partial, derivative of magnetic flux and also the fact that EMF is not necessarily confined to a closed path but may also have radial components as discussed below. A different version, the Maxwell–Faraday equation (discussed below), is valid in all circumstances, and when used in conjunction with the Lorentz force law it is consistent with correct application of Faraday's law. Outline of proof of Faraday's law from Maxwell's equations and the Lorentz force law.

Consider the time-derivative of flux through a possibly moving loop, with area : The integral can change over time for two reasons: The integrand can change, or the integration region can change. These add linearly, therefore: where t0 is any given fixed time. We will show that the first term on the right-hand side corresponds to transformer EMF, the second to motional EMF. The first term on the right-hand side can be rewritten using the integral form of the Maxwell–Faraday equation:  Next, we analyze the second term on the right-hand side: This is the most difficult part of the proof; more details and alternate approaches can be found in references.[5][6][7] As the loop moves and/or deforms, it sweeps out a surface (see figure on right). The magnetic flux through this swept-out surface corresponds to the magnetic flux that is either entering or exiting the loop, and therefore this is the magnetic flux that contributes to the time-derivative. (This step implicitly uses Gauss's law for magnetism: Since the flux lines have no beginning or end, they can only get into the loop by getting cut through by the wire.) As a small part of the loop moves with velocity v for a short time , it sweeps out a vector area vector . Therefore, the change in magnetic flux through the loop here is Therefore: where v is the velocity of a point on the loop . Putting these together, Meanwhile, EMF is defined as the energy available per unit charge that travels once around the wire loop. Therefore, by the Lorentz force law, Combining these, The Maxwell–Faraday equation is a generalization of Faraday's law that states that a time-varying magnetic field is always accompanied by a spatially-varying, non-conservative electric field, and vice versa. The Maxwell–Faraday equation is:

(in SI units) where is the partial derivative operator, is the curl operator and again E(r, t) is the electric field and B(r, t) is the magnetic field. These fields can generally be functions of position r and time t. The Maxwell–Faraday equation is one of the four Maxwell's equations, and therefore plays a fundamental role in the theory of classical electromagnetism. It can also be written in an integral form by the Kelvin–Stokes theorem.[8] Paradoxes in which Faraday's law of induction seems to predict zero EMF but actually predicts non-zero EMFThese paradoxes are generally resolved by the fact that an EMF may be created by a changing flux in a circuit as explained in Faraday's law or by the movement of a conductor in a magnetic field. This is explained by Feynman as noted below. See also A. Sommerfeld, Vol III Electrodynamics Academic Press, page 362.[9] The equipment The experiment requires a few simple components (see Figure 1): a cylindrical magnet, a conducting disc with a conducting rim, a conducting axle, some wiring, and a galvanometer. The disc and the magnet are fitted a short distance apart on the axle, on which they are free to rotate about their own axes of symmetry. An electrical circuit is formed by connecting sliding contacts: one to the axle of the disc, the other to its rim. A galvanometer can be inserted in the circuit to measure the current. The procedureThe experiment proceeds in three steps:

Why is this paradoxical?The experiment is described by some as a "paradox" as it seems, at first sight, to violate Faraday's law of electromagnetic induction, because the flux through the disc appears to be the same no matter what is rotating. Hence, the EMF is predicted to be zero in all three cases of rotation. The discussion below shows this viewpoint stems from an incorrect choice of surface over which to calculate the flux. The paradox appears a bit different from the lines of flux viewpoint: in Faraday's model of electromagnetic induction, a magnetic field consisted of imaginary lines of magnetic flux, similar to the lines that appear when iron filings are sprinkled on paper and held near a magnet. The EMF is proposed to be proportional to the rate of cutting lines of flux. If the lines of flux are imagined to originate in the magnet, then they would be stationary in the frame of the magnet, and rotating the disc relative to the magnet, whether by rotating the magnet or the disc, should produce an EMF, but rotating both of them together should not. Faraday's explanationIn Faraday's model of electromagnetic induction, a circuit received an induced current when it cut lines of magnetic flux. According to this model, the Faraday disc should have worked when either the disc or the magnet was rotated, but not both. Faraday attempted to explain the disagreement with observation by assuming that the magnet's field, complete with its lines of flux, remained stationary as the magnet rotated (a completely accurate picture, but maybe not intuitive in the lines-of-flux model). In other words, the lines of flux have their own frame of reference. As is shown in the next section, modern physics (since the discovery of the electron) does not need the lines-of-flux picture and dispels the paradox. Modern explanations

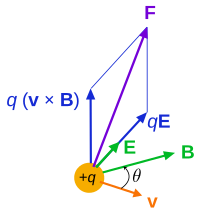

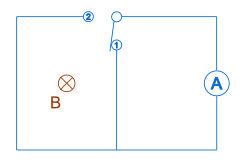

A circuit is not necessarily a loopIn step 1, the paradox can be readily solved: the circuit does not constitute a simple loop of wire, as postulated by Faraday's law of induction; it is rather the union of two loops, because the current can flow through the two halves of the rim (see figure 2). If, on the other hand, one keep only one part of the rim from the radius junction to the brush, then the whole circuit is now a true loop whose shape varies with the time; then Faraday's law applies and leads to correct results. Taking the return path into accountIn step 2, since there is no current observed, one might conclude that the magnetic field did not rotate with the rotating magnet. (Whether it does or does not effectively or relatively, the Lorentz force is zero since v is zero relative to the laboratory frame. So there is no current measuring from laboratory frame.) The use of the Lorentz equation to explain this paradox has led to a debate in the literature as to whether or not a magnetic field rotates with a magnet. Since the force on charges expressed by the Lorentz equation depends upon the relative motion of the magnetic field (i.e. the laboratory frame) to the conductor where the EMF is located it was speculated that in the case when the magnet rotates with the disk but a voltage still develops, the magnetic field (i.e. the laboratory frame) must therefore not rotate with the magnetic material (of course since it is the laboratory frame), while the effective definition of magnetic field frame or the "effective/relative rotation of the field" turns with no relative motion with respect to the conductive disk. Careful thought showed that, if the magnetic field was assumed to rotate with the magnet and the magnet rotated with the disk, a current should still be produced, not by EMF in the disk (there is no relative motion between the disk and the magnet) but in the external circuit linking the brushes,[10] which is in fact in relative motion with respect to the rotating magnet. (The brushes are in the laboratory frame.) This mechanism agrees with the observations involving return paths: an EMF is generated whenever the disc moves relative to the return path, regardless of the rotation of the magnet. In fact it was shown that so long as a current loop is used to measure induced EMFs from the motion of the disk and magnet it is not possible to tell if the magnetic field does or does not rotate with the magnet. (This depends on the definition, the motion of a field can be only defined effectively/relatively. If you hold the view that the field flux is a physical entity, it does rotate or depends on how it is generated. But this does not alter what is used in the Lorentz formula, especially the v, the velocity of the charge carrier relative to the frame where measurement takes place and field strength varies according to relativity at any spacetime point.) Several experiments have been proposed using electrostatic measurements or electron beams to resolve the issue, but apparently none have been successfully performed to date.[citation needed] Using the Lorentz force The force F acting on a particle of electric charge q with instantaneous velocity v, due to an external electric field E and magnetic field B, is given by the Lorentz force:[11]

where × is the vector cross product. All boldface quantities are vectors. The relativistically-correct electric field of a point charge varies with velocity as:[12] where is the unit vector pointing from the current (non-retarded) position of the particle to the point at which the field is being measured, and θ is the angle between and . The magnetic field B of a charge is:[12] At the most underlying level, the total Lorentz force is the cumulative result of the electric fields E and magnetic fields B of every charge acting on every other charge. When the magnet is rotating, but flux lines are stationary, and the conductor is stationaryConsider the special case where the cylindrical conducting disk is stationary but the cylindrical magnetic disk is rotating. In such a situation, the mean velocity v of charges in the conducting disk is initially zero, and therefore the magnetic force F = qv × B is 0, where v is the mean velocity of a charge q of the circuit relative to the frame where measurements are taken, and q is the charge on an electron. When the magnet and the flux lines are stationary and the conductor is rotatingAfter the discovery of the electron and the forces that affect it, a microscopic resolution of the paradox became possible. See Figure 1. The metal portions of the apparatus are conducting, and confine a current due to electronic motion to within the metal boundaries. All electrons that move in a magnetic field experience a Lorentz force of F = qv × B, where v is the velocity of the electrons relative to the frame where measurements are taken, and q is the charge on an electron. Remember, there is no such frame as "frame of the electromagnetic field". A frame is set on a specific spacetime point, not an extending field or a flux line as a mathematical object. It is a different issue if you consider flux as a physical entity (see Magnetic flux quantum), or consider the effective/relative definition of motion/rotation of a field (see below). This note helps resolve the paradox. The Lorentz force is perpendicular to both the velocity of the electrons, which is in the plane of the disc, and to the magnetic field, which is normal (surface normal) to the disc. An electron at rest in the frame of the disc moves circularly with the disc relative to the B-field (i.e. the rotational axis or the laboratory frame, remember the note above), and so experiences a radial Lorentz force. In Figure 1 this force (on a positive charge, not an electron) is outward toward the rim according to the right-hand rule. Of course, this radial force, which is the cause of the current, creates a radial component of electron velocity, generating in turn its own Lorentz force component that opposes the circular motion of the electrons, tending to slow the disc's rotation, but the electrons retain a component of circular motion that continues to drive the current via the radial Lorentz force. Use of special techniques with Faraday's lawThe flux through the portion of the path from the brush at the rim, through the outside loop and the axle to the center of the disc is always zero because the magnetic field is in the plane of this path (not perpendicular to it), no matter what is rotating, so the integrated emf around this part of the path is always zero. Therefore, attention is focused on the portion of the path from the axle across the disc to the brush at the rim. Faraday's law of induction can be stated in words as:[13]

Mathematically, the law is stated: where ΦB is the flux, and dA is a vector element of area of a moving surface Σ(t) bounded by the loop around which the EMF is to be found.  How can this law be connected to the Faraday disc generator, where the flux linkage appears to be just the B-field multiplied by the area of the disc? One approach is to define the notion of "rate of change of flux linkage" by drawing a hypothetical line across the disc from the brush to the axle and asking how much flux linkage is swept past this line per unit time. See Figure 2. Assuming a radius R for the disc, a sector of disc with central angle θ has an area: so the rate that flux sweeps past the imaginary line is with ω = dθ / dt the angular rate of rotation. The sign is chosen based upon Lenz's law: the field generated by the motion must oppose the change in flux caused by the rotation. For example, the circuit with the radial segment in Figure 2 according to the right-hand rule adds to the applied B-field, tending to increase the flux linkage. That suggests that the flux through this path is decreasing due to the rotation, so dθ / dt is negative. This flux-cutting result for EMF can be compared to calculating the work done per unit charge making an infinitesimal test charge traverse the hypothetical line using the Lorentz force / unit charge at radius r, namely |v × B| = Bv = Brω: which is the same result. The above methodology for finding the flux cut by the circuit is formalized in the flux law by properly treating the time derivative of the bounding surface Σ(t). Of course, the time derivative of an integral with time-dependent limits is not simply the integral of the time derivative of the integrand alone, a point often forgotten; see Leibniz integral rule and Lorentz force. In choosing the surface Σ(t), the restrictions are that (i) it has to be bounded by a closed curve around which the EMF is to be found, and (ii) it has to capture the relative motion of all moving parts of the circuit. It is emphatically not required that the bounding curve corresponds to a physical line of flow of the current. On the other hand, induction is all about relative motion, and the path emphatically must capture any relative motion. In a case like Figure 1 where a portion of the current path is distributed over a region in space, the EMF driving the current can be found using a variety of paths. Figure 2 shows two possibilities. All paths include the obvious return loop, but in the disc two paths are shown: one is a geometrically simple path, the other a tortuous one. We are free to choose whatever path we like, but a portion of any acceptable path is fixed in the disc itself and turns with the disc. The flux is calculated though the entire path, return loop plus disc segment, and its rate-of change found.  In this example, all these paths lead to the same rate of change of flux, and hence the same EMF. To provide some intuition about this path independence, in Figure 3 the Faraday disc is unwrapped onto a strip, making it resemble a sliding rectangle problem. In the sliding rectangle case, it becomes obvious that the pattern of current flow inside the rectangle is time-independent and therefore irrelevant to the rate of change of flux linking the circuit. There is no need to consider exactly how the current traverses the rectangle (or the disc). Any choice of path connecting the top and bottom of the rectangle (axle-to-brush in the disc) and moving with the rectangle (rotating with the disc) sweeps out the same rate-of-change of flux, and predicts the same EMF. For the disc, this rate-of-change of flux estimation is the same as that done above based upon rotation of the disc past a line joining the brush to the axle. Configuration with a return pathWhether the magnet is "moving" is irrelevant in this analysis, due to the flux induced in the return path. The crucial relative motion is that of the disk and the return path, not of the disk and the magnet. This becomes clearer if a modified Faraday disk is used in which the return path is not a wire but another disk. That is, mount two conducting disks just next to each other on the same axle and let them have sliding electrical contact at the center and at the circumference. The current will be proportional to the relative rotation of the two disks and independent of any rotation of the magnet. Configuration without a return pathA Faraday disk can also be operated with neither a galvanometer nor a return path. When the disk spins, the electrons collect along the rim and leave a deficit near the axis (or the other way around). It is possible in principle to measure the distribution of charge, for example, through the electromotive force generated between the rim and the axle (though not necessarily easy). This charge separation will be proportional to the relative rotational velocity between the disk and the magnet. Paradoxes in which Faraday's law of induction seems to predict non-zero EMF but actually predicts zero EMFThese paradoxes are generally resolved by determining that the apparent motion of the circuit is actually deconstruction of the circuit followed by reconstruction of the circuit on a different path. An additional rule In the case when the disk alone spins there is no change in flux through the circuit, however, there is an electromotive force induced contrary to Faraday's law. We can also show an example when there is a change in flux, but no induced voltage. Figure 5 (near right) shows the setup used in Tilley's experiment.[14] It is a circuit with two loops or meshes. There is a galvanometer connected in the right-hand loop, a magnet in the center of the left-hand loop, a switch in the left-hand loop, and a switch between the loops. We start with the switch on the left open and that on the right closed. When the switch on the left is closed and the switch on the right is open there is no change in the field of the magnet, but there is a change in the area of the galvanometer circuit. This means that there is a change in flux. However the galvanometer did not deflect meaning there was no induced voltage, and Faraday's law does not work in this case. According to A. G. Kelly this suggests that an induced voltage in Faraday's experiment is due to the "cutting" of the circuit by the flux lines, and not by "flux linking" or the actual change in flux. This follows from the Tilley experiment because there is no movement of the lines of force across the circuit and therefore no current induced although there is a change in flux through the circuit. Nussbaum suggests that for Faraday's law to be valid, work must be done in producing the change in flux.[15]

The magnetic field from the second wire is given by: So we can rewrite the force on wire 1 as: Now consider a segment of a conductor displaced in a constant magnetic field. The work done is found from: If we plug in what we previously found for we get: The area covered by the displacement of the conductor is: Therefore: The differential work can also be given in terms of charge and potential difference : By setting the two equations for differential work equal to each other we arrive at Faraday's Law. Furthermore, we now see that this is only true if is non-vanishing. Meaning, Faraday's Law is only valid if work is performed in bringing about the change in flux. A mathematical way to validate Faraday's Law in these kind of situations is to generalize the definition of EMF as in the proof of Faraday's law of induction: The galvanometer usually only measures the first term in the EMF which contributes the current in circuit, although sometimes it can measure the incorporation of the second term such as when the second term contributes part of the current which the galvanometer measures as motional EMF, e.g. in the Faraday's disk experiment. In the situation above, the first term is zero and only the first term leads a current that the galvanometer measures, so there is no induced voltage. However, Faraday's Law still holds since the apparent change of the magnetic flux goes to the second term in the above generalization of EMF. But it is not measured by the galvanometer. Remember is the local velocity of a point on the circuit, not a charge carrier. After all, both/all these situations are consistent with the concern of relativity and microstructure of matter, and/or the completeness of Maxwell equation and Lorentz formula, or the combination of them, Hamiltonian mechanics. See also

References

Further reading

|

Portal di Ensiklopedia Dunia