|

Congo Reform Association

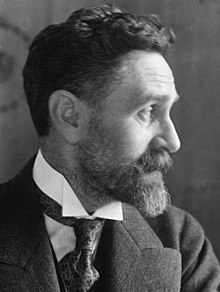

The Congo Reform Association (CRA) was a political and humanitarian activist group that sought to promote reform of the Congo Free State, a private territory in Central Africa under the absolute sovereignty of King Leopold II.[1] Active from 1904 to 1913, the association formed in opposition to the institutionalised practices of Congo Free State's 'rubber policy', which encouraged the need to minimise expenditure and maximise profit with no political constraints – fostering a system of coercion and terror unparalleled in contemporary colonial Africa.[2] The group carried out a global publicity campaign across the Western world, using a range of strategies including displays of atrocity photographs; public seminars; mass rallies; celebrity endorsements; and extensive press coverage to lobby the Great Powers into pressuring reform in the Congo.[3] The association partially achieved its aims in 1908 with the Belgian government's annexation of the Congo Free State and continued to promote reform until disbanding in 1913.[4] Origins: E. D. Morel and the Casement Report In the mid-1890s Edmund Dene Morel was working for Elder Dempster as a shipping clerk based in Antwerp, when he noticed discrepancies between public and private accounts given for the import and export figures relating to shipping from the Congo.[5] Morel deduced from the steady export of firearms and cartridge, against the disproportionate mass imports in rubber, ivory and other lucrative commodities, that no commercial transaction was taking place.[6] He concluded that the use of force was the only explanation: the consistency of the exchange could only be supported by a state-led system of mass exploitation.[7] Resigning from his role in 1901, Morel turned to journalism to investigate and raise awareness about the activities of the Congo Free State authorities, establishing his own journal in early 1903 – the West African Mail.[8] Morel's publications drew from the direct reports and experiences of the missionary community who had for years worked in the Congo, as well as travellers from the region and whistleblowers and former Congo Free States and concession company agents who supplied him with detailed reports and corroborating evidence of widespread atrocities.[9] Morel was a gifted public speaker and prolific writer, giving speeches and publishing articles in other newspapers – foreign and domestic – as well as circulating pamphlets and writing several meticulously researched books on the Congo and Leopold's system.[10] Nathan Alexander has observed that Morel's impassioned campaigning stemmed largely from his belief that the Congo Free State was a corrupt example of modern standards of European colonialism. Alexander noted that as a humanitarian with paternalistic views towards Africans, Morel favoured indirect rule and the promotion of free trade and commerce to gradually develop African territories and peoples along the same lines as Europe.[11] Morel believed the 'Leopoldian system' was the catalyst for the scale of atrocities in the Congo, and that the state's creation of what was in effect a slave-labour force to fuel Leopold's monopolistic enterprise demonstrated he had broken the articles of the Berlin Act in every regard.[12] In Morel's own words, the "King's native policy was the inevitable sequel to his commercial policy". This unified the humanitarians with commercial and political elites in the common cause of reform.[13]  Others shared Morel's view; the Aborigine Protection Society, headed by Henry Fox Bourne, had denounced the CFS as early as 1890 with material collected from Congo missionaries.[14] Sir Charles Dilke MP was another high-profile figure in the British anti-Leopold movement, advocating in parliament in 1897 for the revival of the Berlin Conference to ensure all signatories were adhering to the Berlin Act.[15] In 1903 the collective efforts of Morel and these other actors generated enough public agitation over the Congo Question to produce an impassioned debate in parliament, leading to a resolution forcing government action.[16] However, reconvening the Berlin conference was viewed as geo-politically problematic by the Foreign Office, who instead dispatched their consul in the region to investigate the alleged malpractices of the regime.[17] Roger Casement was the resident British consul in Boma when he was directed by the FO to investigate the allegations against the CFS.[18] From June 1903, Casement travelled throughout the northern interior of the territory aided by the missionaries based there.[19] Their unregulated access to the Congo and its tributaries exposed him to the worst affected areas of the 'rubber tax', and provided him with their testimonies – informing many of his inquiries.[20] Throughout his journey Casement recorded oral testimony from victims of the CFS, seeing first-hand the mutilations and brutalities of the administration and later the systemic use of coercive techniques by state and company officials.[21] Casement's dispatches were viewed as sensationalist and he was recalled by the FO to return to Britain and produce a report for the government.[22] Published in 1904, The Casement Report confirmed the scale of atrocities taking place in the CFS, yet FO officials' interference and lobbying by agents of the CFS led to softening the graphic nature of the report, with the removal of witnesses and perpetrators names undermining its legitimacy.[23] Casement's disillusionment with the decisions of the FO prompted him to seek out Morel who, by 1904, was well established as the leading champion of Congo reform. The two agreed a more holistic approach was needed to effect genuine change in the Congo, with the British government having reduced diplomatic pressure on the CFS following Leopold's announcement that he had set up a commission of inquiry to address Casement's findings.[24] With Morel in-charge they resolved to the creation of the CRA, a unifying movement for the competing agents of reform in the Congo.[25] The Congo Reform Association The weight of the Casement Report, a scathing indictment by a British consular official on the CFS, was crucial in engaging the public with the CRA's message of reform in the Congo – though Casement himself had to abstain from direct involvement due to his government role. Morel led the CRA, achieving widespread public endorsements from church leaders, businessmen, peers and MPs; the movement was characterised as part of the British humanitarian tradition, an appeal that enticed many wealthy donors and powerful supporters to its cause, placing extraordinary pressure on the British government to act.[26] Morel tailored the association's message to appeal to all sections of British society, ensuring it was a non-partisan and Christian issue that Britain must address, his public speeches were inclusive and unifying seeking only to promote reform in the CFS.[27] Morel enlisted fellow journalists in Britain, the United States and sympathetic newspapers in Belgium as agents of the CRA and established regional branches with local activists throughout Britain to promote grassroots movements.[28] The CRA's adoption of contemporary media technologies, like the magic lantern projector, were incorporated into public lectures and seminars, bringing Western audiences face-to-face with photographic proof of the atrocities of the CFS.[29] Charles Laderman has argued that the association's most effective tool was the recruitment of missionaries with firsthand accounts of the regime, two of the most prominent were the Rev. John Harris and his wife Alice. In 1905 the pair returned to Britain where they accepted positions as officers in the CRA, and over the next two years delivered between them six hundred public engagements – bringing photos, props from the CFS, like the chicotte, and their own extensive documentation of what they witnessed to audiences around Britain, later conducting a similar tour in the USA.[30] Felix Lösing has maintained that neither evangelical philanthropy nor humanitarian sentiment but racist dynamics were the main reason for the success of the reform association. Activists in Britain and the United States warned that the atrocities in the CFS destabilised imperial rule on the whole African continent and undermined narratives of white supremacy on a global scale.[31] CRA activism ensured that the Congo Question remained of interest to the general public, fuelling a reciprocal relationship between British parliamentary debates and press coverage that extended globally.[32] The international message of the movement birthed chapters or affiliates across Europe and North America.[33] Outside of Britain, the most effective was the American Congo Reform Association, formed in the United States. Though Morel helped found the ACRA, they sought to distance themselves as an independent American movement due to widespread Anglophobic sentiments among sections of the American populace, particularly German and Irish Americans.[34] Orchestrated effectively by Baptist missionaries and the academic Robert E. Park, it waged a similar publicity and lobbying campaign to the CRA's; public figures like Booker T. Washington and Mark Twain, who famously composed King Leopold's Soliloquy, did much to raise the profile of the movement across the United States.[35] However, Morel and British CRA officials still played a crucial role in the formative phase of the ACRA, transferring and reshaping many of their techniques and practices for American audiences.[36] Lobbying and PR were practised by both the CRA and Leopold's CFS, the king setting up a private and covert Press Bureau in 1904 in reaction to the consistent efforts of the CRA.[37] In December 1906 the ACRA gained momentum with the breaking of the Kowalsky Scandal.[38] The exposé of foreign financial interference in the American political process united various factions across the USA behind the reform movement and demanded government action.[39] It also exposed Leopold's extensive Press Bureau networks to the Belgian press, increasing the already mounting domestic pressure for Congo annexation in Belgium.[40] The publication of the findings of Leopold's Commission of Inquiry, confirming those of the Casement Report, cemented Belgian formal opposition to the CFS and sparked legitimate discussions of government annexation.[41] What became known as the Belgian Solution – the annexation of the CFS by the Belgian government – was viewed by both Britain and the US to be the optimal answer to the Congo Question.[42] Despite Belgium's position as a neutral state, both countries issued a joint démarche on 23 January 1908 demanding that the Belgian government annex control of the CFS and reform the territory in accordance with the articles of the Berlin Act.[43] Morel and the CRA, aware of the geo-political constraints of any alternative, viewed the solution as the most practical for achieving their aims at reform, leading the movement to place public support and endorsement behind the Belgian Solution as early as 1905.[44] The annexation occurred in late 1908 bringing slow and incremental reform, but by 1913 free trade and the effective dismantling of the Leopoldian system, as well as the increasing importance of Belgium to the Entente, led to British recognition of the Belgian Congo.[45] The CRA, acknowledging the gains made, publicly disbanded on 16 June 1913, with Morel declaring that "the native of the Congo is once more a free man", though both he and the movement were aware this was not in fact the case; tensions in Europe and a sharp decline in public support since the 'success' of the annexation, necessitated the declaration and disbandment of the association as the only rationale decision left.[46] See also

Footnotes

References

External links |

Portal di Ensiklopedia Dunia