|

Animals in the Ancient Near East

The ancient Near East was the site of several key developments in the relationship between the animal world and the human species. These include the first animal domestication after the dog, and the first texts on the relationship, which shed further light on relationships already documented for later periods by archaeozoological remains, artifacts, and figurative representations. It is these diverse sources that make it possible to study this subject, which has been renewed in recent years by archaeological research into human/animal relations.[1] From the 10th millennium BC onwards, the Ancient Near East underwent a process of Neolithization, characterized by the domestication of plants and animals. The latter profoundly altered the lives of human societies, modifying their activities, resources, and relationship with nature, notably by relegating most of the animal world to the category of the “wild”. The creation of an increasingly complex society, culminating in the emergence of the state and urbanization, led to other changes, notably the development of large-scale animal husbandry distributed among several actors (royal palaces, temples, nomads). From a utilitarian point of view, humans mobilized animals to provide various services in crucial activities (agriculture, transport, warfare). They used animal products for different purposes (food, wool leather clothing, etc.). The relationship between humans and animals also has a constant symbolic aspect. Many animals were considered vehicles of supernatural forces, and divine symbols, and could be mobilized in various major rituals (sacrifices to the gods, divination, exorcism). The many artistic representations of animals generally refer to this symbolic aspect. The literati also attempted to classify the animals they knew. They developed stereotypes about the characteristics of many of them, which can be found in various literary texts, notably those in which men are compared to animals to highlight a trait of their personality. While some animals had a high symbolic status (lion, bull, horse, snake), others were denigrated and sometimes infamous (pig). Animals of the Ancient Near East Southwest Asia is a vast zoological transition zone, linking different continental areas (Europe, Asia, and Africa). Attested species range from those characteristic of the temperate world in the north to the subtropical world in the far south. The development of complex societies in the Near East brought about changes in the animal world of this region, during the process of “neolithization,”[2] which saw the first experiments in animal domestication, leading to a split between domesticated and non-domesticated animals, and subsequently to the introduction of domesticated animals outside the Middle East. Domesticated animalsThe domestication process and its evolution According to D. Helmer, domestication can be defined as “the control of an animal population through the isolation of the herd, with the loss of panmixia, the suppression of natural selection and the application of artificial selection based on particular traits, either behavioral or cultural. Animals become the property of the human group and are entirely dependent on it.[3] This differs from taming, which only involves isolated individuals of a wild species. The process of animal domestication is not easy to identify.[4] Research into archaeozoology (the discovery of animal remains on archaeological sites) is helping to shed light on this phenomenon. This involves studying whether an animal is more present than another, which may indicate that it has been domesticated (but this may also be an example of selective hunting), or whether its anatomy has been modified by domestication.[5] Identifying the date of first domestication is therefore complicated, but since we're talking about very remote periods, dating is very vague in any case. Identifying a place or region of domestication is also a difficult task, as discoveries can rapidly alter our knowledge. What's more, there is a tendency to think that there may have been several foci of domestication for certain species, even on the scale of the Middle East.[6] Domestication is, therefore, a complex, long, gradual but coherent process: the domestication of ungulates took place over roughly a millennium, illustrating the fact that societies of the time were able to employ the same techniques to domesticate several species to facilitate their way of life.[7] Domesticated species are often species that had previously been heavily hunted, and it is assumed that domestication may have been preceded by specialized or even selective hunting, favoring a certain type of game, whose movements were gradually organized, along with its diet and breeding grounds, within a specific territory.[8] But a much-hunted species like the gazelle has never been domesticated. Domestication may also have occurred after the capture of animals, which human groups continued to control. In concrete terms, the phenomenon is one of the elements marking the beginning of the Neolithization process, undoubtedly contemporary with the first experiments in the domestication of plant species in the Near East, between the southern Levant and southern Anatolia. Experiments in intensifying animal herd management took place a little earlier, probably leading to the first experiments in domestication as early as 9500 BC (in Pre-Pottery Neolithic A), but this remains complex to detect as there was no morphological evolution of animals at this stage. Domestication certainly takes shape from 8500-8300 (during Pre-Pottery Neolithic B), a period for which morphological changes are indisputable.[9][10][11][12] The search for the reasons for animal domestication has given rise to several hypotheses, in line with those developed to explain the “Neolithic revolution.” One widespread idea is that domestication was a consequence of climate warming after the end of the last Ice Age, which led to a reduction in the resources available to human groups (plants and animals), who then sought to control them to make better use of them. This was undoubtedly a determining factor, but it should not relegate other factors to the background.[13] Moreover, animals were not necessarily domesticated for their meat, as hunting seems to have remained the main means of obtaining it until around the 8th millennium BC, even if the meat or fat of farmed animals may have helped balance the diet of early farmers, as did milk.[14][15] Domestication is inextricably linked to a process of species selection by man. Domesticated animals are not potential food competitors for humans, except the dog (or cat, little attested in the ancient Near East), which plays the specific role of a human companion. On the contrary, they are food partners for farmers, who feed on the seeds of the cereals and legumes they grow, but cannot assimilate the cellulose contained in straw, stems, and leaves, unlike domesticated ruminants: there may therefore be a link between the domestication of plants and that of animals. It also can be noted that selection precedes domestication, and continues afterward, with man controlling animal reproduction. In the long term, this leads to changes in domesticated species, notably morphological and anatomical, such as the loss of horns by sheep and, above all, a reduction in their size, which has enabled archaeozoologists to identify the first domesticated animals.[16] It also alters the reproductive cycle of animals, since when they are domesticated they no longer have a rutting and calving period, and can therefore procreate all year round. According to “symbolic” approaches, the domestication of animals is accompanied by a change in man's conceptions of nature, as he realizes that he can seek to control and dominate it.[17][18] This ties in with the theses developed by J. Cauvin, who sees Neolithization as the consequence of a “revolution in symbols,” and sees the domestication of animals above all as the consequence of “a human desire to dominate beasts.”[19] The human-animal relationship as documented is now seen less in terms of domination than in the past, as a less unbalanced relationship than it might seem. In any case, the impact of animal domestication on human society cannot be underestimated, as it has profoundly altered the utilitarian, economic, biological (pooling of viruses), and social aspects of human-animal communities, and symbolic, with the distinction between the wild, which is external to human society, and the domesticated, which is fully part of it. In building a society with domesticated animals, man is thus led to change himself, by adapting to his partners, who cannot be reduced to mere dominated beings.[20][21] The phase of animal domestication was followed by another significant evolution, which saw animals used not only for the products they provided after slaughter (skin, meat, fat, bones), but also for renewable, or secondary, products that did not require them to be killed (wool, hair, milk) and their labor power (draught, beating). This stage has been dubbed the “secondary products revolution” by A. Sherratt.[22] Originally placed in the 4th millennium BC (i.e., the Final Chalcolithic), this evolution is undoubtedly older, since milk from domesticated animals may have been commonly used from the 7th millennium BC onwards according to the analysis of archaeological documentation from these periods, and perhaps even earlier, as early as the end of Pre-Pottery Neolithic B. Similarly, the traction power of cattle could have been used as early as the Neolithic, as well as sheep's wool and goat's hair, although this remains difficult to establish archaeologically. The 4th millennium BC saw an intensification in the exploitation of these secondary products, accompanying the emergence of state structures and urban societies, with their institutions and vast herds.[23] Domesticated animals in the Ancient Near East  The first domesticated animal was the dog, probably as early as the end of the Palaeolithic: dogs have been found buried with humans from the Natufian period (c. 12000-10000), at Mallaha and Hayonim in the southern Levant. The geographical location of its domestication is the subject of debate, and there is no evidence to suggest that it was domesticated in the Near East. The fact that it was the first domesticated animal, in a pre-Neolithic society that did not practice agriculture, sets it apart from other animals in its relationship with man from the very beginning.[24][25][26] The Neolithic was the great period of animal domestication when the four ungulates that later provided the bulk of the region's domesticated animals were domesticated. The phenomenon took place over a few centuries and was centered on the Taurus region and the northern Levant (upper Euphrates and Tigris valleys), with rapid spread to the southern Levant and the Zagros to the east. Goats seem to have been the first to be domesticated, but recent research has highlighted the fact that the other two quickly followed. The goat appeared between 8500 and 8000, following the domestication of its wild species (Capra aegagrus) living in the highlands from Anatolia to Pakistan.[27][28][29] This animal could have been domesticated in several places at the same time: the Taurus region and Syria (Abu Hureya), and in the Zagros (Ganj-i Dareh). Sheep were domesticated at the same time from mouflon in the dry regions of eastern Anatolia and northern Iraq and Iran, again in the Taurus and northern Levant (Hallan Çemi, Nevalı Çori), and took longer to spread to sites in the southern Levant and Zagros, where they only became important two millennia later.[27][28][29] The first cattle were domesticated a little later than sheep and goats, in the Middle Euphrates and Taurus, although recent research tends to date their domestication to a period contemporary with the other two. The auroch is the origin of the most common domestic cattle (Bos taurus: cows, oxen, bulls).[30][31][32] The pig was domesticated from the wild boar, in the same place and at roughly the same time or a little later (Cafer Höyük, Hallan Çemi), and was soon found at sites in the southern Levant and Zagros.[33] But unlike the previous three, its breeding was never widespread and declined from the 2nd millennium onwards.[34] In any case, by the beginning of the Pottery Neolithic, around the second half of the 7th millennium BC, all four domesticated ungulates were present at sites throughout the Middle East.[35] Other animals were domesticated later, but in regions outside the Middle East, from where they were introduced.[36] Domesticated buffalo are attested in Mesopotamia in historic times.[37] The equids domesticated in the Near East are donkeys, probably derived from the domestication of the wild African donkey in the 4th millennium, in Egypt and the Middle East, with probable cross-breeding with the wild Asian donkey (hemione or onager).[38][39][40] Domesticated horses appeared in Mesopotamian, Syrian, and Levantine sources towards the end of the 3rd millennium and the beginning of the next, and their use spread rapidly thereafter, making them one of the main domesticated animals alongside those that were domesticated first.[39][40] The earliest traces of cats in undoubtedly domesticated condition date back to the Middle Kingdom of Egypt, but this animal may well have been domesticated much earlier, as shown by the discovery of a cat burial in Cyprus dating back to the 8th millennium.[41] Unlike in ancient Egypt, the dromedary is rarely mentioned in ancient Near Eastern sources.[42] The dromedary was domesticated no later than the middle of the 3rd millennium or the beginning of the following one, probably in Arabia, and spread to the Near East in the 1st millennium. The Bactrian camel was probably domesticated around the same time in Central Asia, then spread to the Middle East during the 2nd millennium. These two animals became very popular in desert environments from the first half of the 1st millennium.[43]  As for poultry, now it's known that the hen was domesticated in Eastern Asia around 6000 BC, and is attested in Mesopotamia in the 3rd millennium.[44] As for pigeons, geese, doves, and ducks, attested very early around Neolithic settlements, there are not enough sources to know whether they were commonly bred, and therefore whether some had been domesticated. The first clear traces of their breeding date back to the 1st millennium.[45] Bees are a case in point. Their honey was probably exploited very early on in prehistory, but man did not seek to control them until the 3rd millennium, in Egypt. Beekeeping is mentioned in the Hittite laws.[46][47] Wild animalsAmong the non-domesticated ungulates,[48][49] the hippotragus are mainly represented by the oryx, divided into two subspecies in the Near and Middle East (Scimitar and Arabian). Antilopinae (gazelles) are divided into various species living in arid and semi-arid biomes from North Africa to Central Asia and India. It's clear that they were hunted extensively by Natufian societies: is this selective hunting, or a pre-domestication that failed? Non-domesticated Caprids include the Nubian ibex (Capra nubiana), the wild goat (Capra aegagrus), and the mouflon. The wild bovines (auroch, bison) that lived in the lower regions of the Near and Middle East in ancient times have now disappeared.[50]  The most numerous non-domesticated carnivores are wolves. Other non-domesticated canids included jackals and various species of fox. Among felines, the Eurasian wildcat is undoubtedly the most widespread. In ancient times, lions lived in the lower regions of the Middle East, but are no longer found today.[51][52][53] The Caspian tiger lived in northern Iran and Afghanistan until the early 19th century AD. Leopards are still found in mountainous and hilly regions of the Near East. The brown bear is also a resident of the forests of southwest Asia.[54] Cervids are found in vegetated, open, and temperate terrain. Three species are indigenous to the Near and Middle East: the stag, now present in Turkey, the Caucasus, and northern Iran; the roe deer, the smallest of the group, found in the same areas; and the fallow deer, medium-sized, divided into two subspecies living in two different zones (European/Anatolian and Mesopotamian/Persian).[55] A type of Syrian elephant was also found in the lowlands and open forests of Syria and even Iran until the beginning of the 1st millennium. It was close to the Asian elephant, based on available representations.[56] Hippopotamuses still lived in the southern Levant until the 1st millennium. Little information is available on rodents and bats, even though they are the most numerous mammals. Certain rodents emerged with the advent of sedentarization and the agricultural economy: the house mouse, a human commensal, appeared in Natufian Palestine, from wild mice. The spiny mouse is very common in dry regions.[57] There were also beavers, now endangered by the retreat of the forest.  Marine mammals include the Caspian seal, the Mediterranean monk seal, and the dugong, which is found in the Persian Gulf[58] and sometimes in the Red Sea; among cetaceans, dolphins are much mentioned in ancient sources (in the Mediterranean Sea, Red Sea, Persian Gulf).[59] Among birds, resident species are to be distinguished from migratory species. As mentioned above, there is no real evidence that pigeons, geese, or doves were domesticated, any more than ducks. Ostriches were still found in the Levant and Arabia in ancient times. Many migratory species fly over Eurasia to winter in the Near East, North Africa, or South Asia.[60][61] The insects most frequently mentioned in ancient Near Eastern texts are locusts, notably the desert locust, and grasshoppers (generally under a generic name that does not allow them to be distinguished),[62] but bees, butterflies, dragonflies, flies, and mosquitoes are also mentioned. More than 70 species of scorpion are currently listed in the geographical area concerned, and the same must have been true in the past. Fish are poorly represented in archaeological remains, or even in texts, but representations of them are often found, indicating their importance.[63] Reptiles appear in some texts, before snakes. Gastropods, notably the murex, are more easily identified by their remains. Finally, Mesopotamian texts refer to crustaceans, notably shrimps.[64][65] Animals and people: utilitarian and recreational aspectsFrom the Neolithic period onwards, human societies began to control a large proportion of the animals that were potentially useful to them. This brought about a major change in the day-to-day relationship between humans and animals, disrupting how human communities integrated animals into their midst, even if earlier forms of animal husbandry, such as hunting and fishing, remained in place. With the emergence of state-run societies and large organizations capable of handling a wide range of economic activities on a larger scale, animal control took on a new dimension. This gave people access to animal products for a variety of purposes, as well as invaluable auxiliaries for work and travel at a time when technical means were limited and muscle power was still by far the most widely used, giving animals a primordial utilitarian function in the functioning of human societies. This sometimes leads to more recreational or intimate relationships between humans and animals. At the same time, people also have to deal with various risks associated with domestic and wild animals. Disposing of animals: hunting, fishing, and breedingPeople obtain wild animals by hunting or fishing.[66][67][68] These activities, which pre-date the Neolithic period, can be carried out by individuals or groups, working for themselves or for institutions such as the royal palace, in which case they constitute their profession. Unless they were in the latter case, hunters and fishermen have left very few traces, since large organizations are the main providers of our written sources. The Epic of Gilgamesh shows a hunter using traps to capture animals. But the hunters most often mentioned are kings, for whom this activity was highly valued, both as preparation for war and for symbolic reasons (see below). In any case, from the 4th millennium onwards, hunting became a secondary activity in the provision of food and was therefore neglected by large organizations. Ancient Near Eastern hunters were able to hunt a wide variety of wild animals.[69] There is quite a lot of knowledge about the fishermen of the rivers and marshes of southern Mesopotamia towards the end of the 3rd millennium because the state controlled their activities:[70] they were organized into groups supervised by a chief, who distributed subsistence rations to them. Mesopotamian texts from the 2nd millennium distinguish between fishermen who worked at sea, in the marshes, or inland. They could fish with lines and hooks, or with nets and creels.  Developed from the Neolithic onwards, perhaps after “selective” hunting of certain animals that were later domesticated, the activity of raising domesticated animals (or simply “managing” animals such as farmyard birds or bees) is more productive for man than hunting or fishing, and offers a much safer resource, without the hazards of hunting, since it organizes control of the animal's entire life (reproduction, growth, movements, choice of the right moment for slaughter). With the development of more complex societies from the 4th millennium onwards (social and political complexification with urbanization, the emergence of the State, and the development of administration), animal husbandry took on a new dimension, becoming more specialized and systematized, at least in the circles of power.[71][72][73] It is in this context that the emergence of various specialized professions linked to animals can be dated: hunting, fishing, herding, fattening, training, processing of various animal products, etc.; previously, these activities were not subject to such a thorough division of labor. B. Hesse proposes to distinguish three forms of animal husbandry in the historical societies of the Ancient Near East:[74]

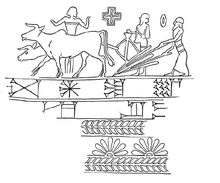

Sheep are by far the most widely raised animals because they require minimal food and can adapt to various climatic environments. Goats are less frequently mentioned in documentation but likely held significant importance.[28][29] Cattle, though fewer in number, are probably more useful, as they not only provide large quantities of food (meat and milk) and hides but also represent a considerable labor force.[31][32] They are the most financially valuable. Texts often distinguish between various types of animals within the same species based on their appearance or geographical origin, which implies specific traits.[80] For example, there are mentions of fat-tailed sheep, mountain sheep, or "Amorite" sheep. Using the different characteristics of animals within the same species, breeders could engage in crossbreeding to enhance the qualities of the breeds.  Horse breeding was the area that received the most attention.[81][82] This is due to the significant military value of the horse, which over time also acquired a prestige status, elevating it above other domesticated animals.[83] The Kassites and Hurrians appear to have played a major role in developing the art of horse breeding from the middle of the 2nd millennium BC. Horse breeding gave rise to a specialized body of literature: hippiatric texts (focused on horse medicine) discovered in Ugarit, Syria,[84][85] and training advice for properly raising horses provided by a Hurrian expert named Kikkuli, found in a Hittite text.[86][87] Administrative records from other contemporary sites (such as Assur and Nippur) also reveal the extensive care devoted to horse breeding by the elites of the various kingdoms in the ancient Near East. Livestock farming frequently generated disputes, as reflected in legislative texts that shed light on certain aspects of this activity. Domesticated animals could cause damage; for instance, the Code of Hammurabi addresses situations where cattle escape their owner's control and kill someone or cause property damage. Other issues arose when individuals entrusted animals to a shepherd, as described in various Mesopotamian, Hittite, and Exodus laws, and the animals were stolen, killed by wild animals, died, or miscarried by accident. It was also necessary to prevent herds from damaging cultivated fields. In such cases, legislators primarily aimed to determine whether the owner or the shepherd was responsible and to establish appropriate fines and compensation.[88][89] Products Provided by Animals for Food and Craftsmanship Animals were exploited for the food products they could provide to humans.[90][91][92][93] Meat consumption was occasional for most inhabitants of the ancient Near East and significantly less common compared to the consumption of plant-based foods.[94] From the 4th millennium BC onward, meat primarily came from animal husbandry, with hunting becoming a much less significant source. The most commonly consumed meats were from sheep, but goats, cattle, pigs, and occasionally poultry were also eaten, along with hunted animals such as gazelles, deer, wild boars, and wild birds, as well as certain types of mice. Fish were also part of the diet of the ancient inhabitants of the Near East, alongside some crustaceans and turtles. Certain insects, such as locusts and grasshoppers, were also consumed, offering a valuable protein source. Meat could be eaten fresh, but to preserve it for longer periods, it needed to be salted, dried, or smoked. Fish and insects could also be prepared in sauces. Pork fat and the blood of certain animals were used in the preparation of specific dishes. Cattle and goats provided milk, which could be consumed directly or processed into butter, buttermilk, whey, or cheese—several varieties of which are known from ancient texts.[95][96] Nomadic groups, traditionally involved in herding, likely had greater access to these products than the majority of sedentary populations. Eggs from both domesticated and wild birds were also eaten. Honey was a highly prized product.[47] While animals were primarily consumed for nutritional purposes, they occasionally contributed to the preparation of medicinal products as well. Humans raised and hunted animals to obtain materials for clothing, such as sheep’s wool, goat hair, and the hides of both domesticated and wild animals.[97][93] Techniques were developed to process these raw materials, including tanning hides to produce leather[98][99] and dyeing, sometimes using murex shellfish to create the prized purple color.[100] These animal-derived materials provided an alternative to linen for making garments. Leather was also used to produce bags, skins for carrying liquids, animal harnesses, furniture components, and weaponry elements. Wool fibers and animal hair could be used to make ropes and threads. Animal fat found utility as a lubricant in various crafts, such as textiles, metallurgy, and cart-making. Manure served as a source of fuel and even in construction. Animal tendons were used in shoemaking, sewing, and even carpentry. Artists and craftsmen also worked with bone, shells, and ivory, which were valued materials for creating luxury items such as cosmetic boxes, statuette components, and furniture inlays.[101][102] Ivory was sourced from animals like hippopotamuses, elephants, and even dugongs. Objects were also fashioned from the horns of goats, sheep, or gazelles, including containers. Animals as Aids to Humans in Various Activities Domesticated animals have often served as essential aids to humans in significant activities such as agriculture, transportation, hunting, and warfare. This role likely led ancient people to categorize animals into those that were productive and those that were not. The dog, being the first domesticated animal, was highly valuable for assisting humans in hunting, herding livestock, and guarding homes. Tamed birds of prey could also aid hunters, as depicted in certain texts and cylinder seals.[103][104] In agriculture, draft animals, primarily cattle and likely donkeys, were used to pull plows during tilling. These same animals were employed after harvest for threshing grain, helping to separate the ears from the grains.[105]  Another major activity where the labor of domesticated animals was essential was transportation. Animals were used to pull carts (as draft animals) or to carry goods (as pack animals). Although donkeys might have been harnessed to pull sledges before the invention of the wheel in the late 4th millennium BC and later used for heavy four-wheeled carts, this role was mainly reserved for cattle and later for horses. The introduction of horses in the 2nd millennium BC enabled the creation of lighter, faster two-wheeled chariots.[106] Donkeys were vital for carrying loads until the early 1st millennium BC when Arab tribes began breeding camels and dromedaries. These animals significantly changed trade practices due to their remarkable endurance in hot and arid environments, allowing humans to traverse longer desert routes. For long-distance transport, caravans were organized as early as ancient times, notably in the Assyrian trade networks in Central Anatolia at the start of the 2nd millennium BC.[107] However, horseback riding remained underdeveloped in the ancient Near East, only gaining prominence from the 1st millennium BC, primarily for hunting and warfare.  In warfare, animals were crucial for transporting logistical equipment via caravans and directly on the battlefield as draft and riding animals. Military chariots appeared in Mesopotamia by the end of the 3rd millennium BC, initially heavy four-wheeled carts with solid wheels pulled by donkeys or other equids (donkeys, hemiones, possibly horses or hybrids of these species). By the second quarter of the 2nd millennium BC, advancements in horse breeding—driven by various peoples like the Hurrians, Kassites, and Indo-Aryan groups—led to the development of lighter, two-wheeled, spoked chariots. These were more maneuverable and faster, sparking a military revolution in battlefield tactics during the latter half of the 2nd millennium BC, enabling rapid offensives and surprise raids, as evidenced by the Battle of Kadesh.  In the early 1st millennium BC, the Assyrian army formalized the use of chariots pulled by two horses and manned by three soldiers (a driver, an archer, and a shield-bearer).[108] The Assyrians also pioneered the development of mounted cavalry, which had previously been scarcely used, possibly inspired by their Aramean adversaries. The invention of the martingale in the early 8th century BC further expanded cavalry use, leading to the formation of dedicated cavalry units.[109] The horse’s central role in military practices—and by extension, hunting—explains how it quickly became a noble and highly prized animal with a high market value. This prestige led to the creation of specialized treatises on its breeding and care, a privilege not extended to other animals. Eventually, the horse became a warrior symbol in artistic depictions.[110][83] The specialization of certain peoples and regions in horse breeding, such as the Urartians, Medes, and Scythians, gave them a significant advantage on the battlefield. The Movement of AnimalsHumans have been responsible for the relocation of various animals throughout history. The movement of domesticated animals from their original centers of domestication to new regions is a process that took the longest time but covered the greatest distances. For instance, the chicken, domesticated in East Asia around 6000 BCE, was introduced to the Near East three millennia later and subsequently spread westward.[111] Domesticated animals from the Near East were also disseminated to other regions, including Europe. Archaeozoological remains and ancient texts indicate that animals could travel long distances on certain occasions. To transport meat over great distances, it had to be smoked, dried, or salted. Alternatively, live animals (including fish) could be transported and then slaughtered upon arrival if they were intended for consumption. Fish from the Persian Gulf or the Mediterranean have been found at sites in Upper Mesopotamia, such as Tell Beydar, and even sea shrimp were brought to Assyria.[64] Long-distance animal movements could also occur selectively for the pleasure of rulers who sought to assemble collections of exotic animals. They had several means to acquire these animals. Diplomacy was one such method: King Zimri-Lim of Mari, for example, received an Egyptian cat through the diplomatic exchange. Additionally, animals were sometimes presented as tributes. Assyrian kings demanded exotic animals from defeated peoples, and in some cases, they captured these animals during military campaigns.[112][113][114] On shorter, yet sometimes significant distances, domestic animals were often herded in groups for seasonal migrations similar to transhumance. This practice helped avoid keeping livestock in cultivated areas during plant-growing seasons and allowed herds to move toward regions with more abundant water sources and richer pastures. These destinations could include steppe areas during the wet season when they were covered in grass or hilly and mountainous regions during summer for cooler climates and denser vegetation.[75] Large institutions employed nomadic shepherds to manage these migrations. In dangerous regions, herds were sometimes accompanied by soldiers for protection. Evidence of this practice appears in the archives of the Uruk temple in the 5th century BC, which deployed archers alongside shepherds to escort their sheep to graze in Upper Mesopotamia, particularly around Tikrit, where the climate was milder and the grazing lands more plentiful.[115] Institutions also organized redistribution systems for animals, sometimes on an interregional scale, such as the BALA system under the Third Dynasty of Ur. Regions with abundant livestock were required to deliver animals to the state as a form of tax. The state could then redistribute these animals to other parts of its territory, especially to major religious centers like Nippur, where the animals could be offered as sacrifices to the great god Enlil. It is estimated that around 60,000 sheep were moved annually during the late reign of Shulgi (2094–2047 BCE). However, this system was exceptional and only lasted a few years.[116][117][118] It is difficult to determine how much trade contributed to livestock supply in communities, as animals were likely bred and used primarily on a local level.[119] Only the wealthiest individuals were probably well-supplied by institutions, particularly through the redistribution of animal parts from sacrificial offerings, giving them access to established exchange networks. Recreational, Emotional, and Prestigious Functions When considering human recreational practices involving animals, the challenge lies in the fact that historical sources rarely mention them explicitly. Wild animals could participate in celebrations organized by kings, notably during the Third Dynasty of Ur, where there is a record of a bear being displayed.[120] However, it is evident that exotic wild animals were highly valued by the great rulers of the ancient Near East, from the kings of Akkad and Ur III to those of the Assyrian Empire, as previously noted regarding the movement of animals within royal courts. Assyrian sources reveal the main purposes behind these animal transfers: the creation of kinds of "zoos" in royal gardens, where exotic animals were gathered,[121] and royal hunts conducted within these spaces. These hunts are described in royal annals and depicted in the bas-reliefs of a palace in Nineveh, showing King Ashurbanipal hunting lions.[122][123][124] Royal hunts were commonly represented in ancient Near Eastern art as a means of glorifying and legitimizing the ruler's power, emphasizing his warrior spirit and mastery over the animal kingdom.[125] Certainly, kings and other participants may have derived pleasure from these activities; however, this personal enjoyment was not the reason these events were visually or textually recorded. The coexistence of humans and domesticated animals fostered more intimate, emotional relationships. This is evident in the documentation of names given to cattle in various records from Babylonia during the early second millennium BC and the later periods. These names reflect the notion that these animals, costly and vital to farmers as work companions, could be regarded as full-fledged members of the family.[126] Equines, on the other hand, were prized for the prestige they conveyed during public displays of a ruler's or deity's power. In Amorite Syria (early second millennium BC), the donkey or mule held the highest prestige. King Zimri-Lim of Mari, for example, was advised to enter a city riding one of these animals (or in a sedan chair) rather than a horse—an animal he preferred but that was considered less dignified at the time.[76] However, horses eventually became the ultimate prestige animals, symbolizing the strength of kings and gods. Royal stables housed the most remarkable stallions, sometimes chosen by the deity himself through divination rituals. These horses received exceptional care and were paraded during grand ceremonies, such as the white horses pulling the chariot of the god Ashur during the New Year festival.[78] Nevertheless, it is difficult to assert the existence of "pets" in ancient Near Eastern societies. There is little evidence to suggest that animals were raised purely for the personal pleasure of their owners in private settings.[127] Risks Related to Animals Human societies have regularly been exposed to risks associated with the behavior of certain wild animals with which they interact. For example, several letters from Mari mention lion attacks on humans and their livestock in the 18th century BC Syria.[128] Scorpions and snakes—especially the fearsome horned viper—also posed significant threats. Some of the oldest known incantations were created to combat these dangers; similarly, the bronze serpents in the Bible were meant to heal snake bites.[129] Several of the Ten Plagues of Egypt described in the Torah were directly caused by wild animals and reflect disasters that could affect ancient Near Eastern societies, particularly invasions of mosquitoes and, more notably, swarms of locusts and other similar insects.[130] Assyrian records also mention the damage that moths could cause, particularly to fabrics.[131] Various methods were developed to combat these threats: airing out fabrics infested by moths and drowning locust larvae in irrigation canals. However, the ancients often resorted to prayers and incantations when faced with the dangers posed by insects.[62] Other risks were connected to the practice of domestic animal husbandry and are addressed in legal texts. The Code of Hammurabi, for instance, mentions the damage or injuries (sometimes fatal) that oxen could inflict, as well as attacks on herds by wild animals. It also refers to outbreaks of epizootic diseases and other illnesses occurring in livestock enclosures.[88][89] These epidemics are also noted in everyday records, such as the letters from Mari.[128] The Animal as a Symbolic "Object"The bond formed between humans and animals led to a relationship that goes beyond mere utilitarian use, taking on a symbolic nature. Since prehistoric times, humans have turned animals into cultural objects. They became symbols of supernatural forces and means of communication with the divine world in various ritual acts. Certain taboos were also established, prohibiting specific interactions with certain animals. Intellectually, humans sought to classify the animal world and developed precise mental representations of animal characteristics. This explains the frequent presence of animals in art, typically driven by symbolic motivations. Divine and Mythical Animals Animals have been present in the religions of Near Eastern cultures since the Epipaleolithic and early Neolithic periods. The pillars of the Göbekli Tepe sanctuary bear depictions of wild animals (as animal domestication had not yet begun, except for dogs). In the early Neolithic period at sites like Çatal Höyük and Mureybet, buildings that likely served as sanctuaries contained bucrania—bovine skulls used for ritual purposes.[132] According to J. Cauvin, the bull represented a male, fertile principle, complementing the mother goddess.[133] However, there is no definitive evidence that animal deities were ever worshipped in ancient Near Eastern civilizations; only anthropomorphic gods and goddesses are historically confirmed. Nonetheless, certain animals were closely associated with deities, serving as their symbols—these are known as "symbolic animals" or "attribute animals."[134][135] These could be real animals (almost never domesticated animals, except for the dog associated with the Mesopotamian goddess Gula) or mythological creatures. Among real animals, the bull was the attribute of the Storm God (Adad, Teshub), representing his fertilizing aspect, while the lion symbolized Ishtar’s warrior side. The stag was linked to Hittite deities that protected nature (DLAMMA). Among mythological creatures, the dragon-serpent (mušhuššu) was associated with Marduk (among others), and the Capricorn (suhurmašu) with Ea. Statues of these animals could be used in rituals just like other divine symbols. For instance, stag effigies received libations and food offerings during the Pushkurunawa mountain ritual in the major Hittite festival AN.TAH.ŠUM.[136] It seems that some temples in late-period Syria and the Levant housed live animals, like lions symbolizing the fertility goddess, alongside other animals, not for sacrifice but for their sacred nature. Similarly, some gods were adorned with animals for display, particularly high-quality horses.[78]  In contrast, the Hebrew Bible prohibits identifying God with animals, as exemplified by the "golden calf" in Exodus. However, God is often metaphorically compared to animals in literary expressions (e.g., a vulture watching over).[137] A notable exception is the case of the "bronze serpents" (nehuštan) found in temples, which seemingly served to heal snake bites—a practice the Bible attributes to Moses. Bronze serpent artifacts have been unearthed in several Near Eastern sanctuaries.[129] Later, Christian tradition adopted the dove—previously linked to goddesses of love—as a symbol of peace and a messenger, representing the Holy Spirit.[138] Ancient Near Eastern mythologies feature numerous imaginary animals and spirits or demons with animal traits, often appearing as hybrids.[139] This vast mythological fauna includes scorpion-men, fish-men, griffins, winged bulls and lions, winged horses resembling Pegasus,[110] mermaids, various types of "dragons" (serpent-dragons, lion-dragons), and the lion-headed bird Imdugud/Anzû. There is also the hybrid demon Pazuzu. The demoness Lamashtu is depicted with a dog's face, donkey ears and teeth, and bird talons. The Bible also references some of these creatures, such as Leviathan and various types of dragons.[140] Certain animals were used to represent constellations in the sky. Regarding Mesopotamian zodiac signs, there are the Crab (Cancer), the Lion (Leo), the Scorpion (Scorpio), and the Capricorn (Capricornus).[141] Animals in Worship and Religious Practices More concretely, animals are often used in religious worship. Many animals were offered as sacrifices to gods, almost exclusively domesticated animals—primarily sheep, along with goats, and even birds in Hittite practices. Their meat (usually prepared) was presented as a meal to the deity, with portions later distributed among priests and political authorities.[142][143][144] In ancient Israel, animal sacrifices were also practiced, with distinctions made between offerings. For example, in closure and communion sacrifices, part of the meat was consumed by humans, while the rest (particularly the fat) was reserved for God and burned. In contrast, burnt offerings (holocausts) involved the complete incineration of the animal, symbolizing its full consumption by God.[145] Another form of animal sacrifice for rituals was hepatoscopy—divination performed by reading the liver of lambs. Animal-based divination could also occur without sacrifice, such as interpreting the flight patterns of birds or, in Hittite regions, the movements of snakes. Animals are frequently mentioned in omen texts, especially when interpreting abnormalities found in newborns. In this way, animals served as intermediaries through which gods could send messages to humans.[146][147][148][149][150] Animals also played roles in rituals, notably for purification, in sealing alliances (for example, the bloody sacrifice of young donkeys often formalized diplomatic agreements during the Amorite period), or during burials, where they were interred alongside the deceased—commonly equines, but also dogs.[19][151] Exorcism rituals often involved animals when a substitute was needed to carry the threat away from a human. The animal would take on the affliction and then be sacrificed, thus removing the threat (sometimes burned or buried). Alternatively, the animal could absorb the evil and then be released far away, symbolizing the human’s purification—a practice akin to the "scapegoat" ritual. In Mesopotamia, goats were preferred for these rituals, along with less commonly sacrificed animals such as pigs, dogs, birds, and fish. Sometimes, the substitute animal was even dressed in women’s clothing to more fully embody the person needing healing. In the common analogical magic rituals of the Hatti, where threats to a person were addressed using vivid comparisons, animals were also referenced in incantations, even if they were not physically present.[152] Animals in ArtArtists of the ancient Near East depicted animals using various visual expression forms they were accustomed to: stone and metal bas-reliefs, cylinder seals, tableware; three-dimensional representations such as statues, standards, weights, or zoomorphic ceramics; and wall or ceramic paintings, though often poorly preserved. The materials used were just as diverse: terracotta, different types of stone and metals, ivory, etc. (textiles and wood have disappeared over time).[153]

These various forms of representation have been present since Neolithic societies in the ancient Near East: the bas-reliefs on the pillars of Göbekli Tepe, paintings, statues, and bull skulls (bucrania) of Çatal Höyük, and the painted ceramics of the Samarra period, for example. Thus, traditions and stereotypes in animal representations are evident across different regions, sometimes sharing common traits due to cultural exchanges. Recurrent motifs can be observed, emphasizing specific aspects of the animals depicted—for example, the roaring lion or bovines and caprines with prominent horns. However, artistic evolution is evident: prehistoric depictions of animals are generally highly stylized, with artists not seeking realistic portrayals, likely because these representations served purely symbolic purposes. Narrative and naturalistic approaches developed only later (making it difficult at times to identify the animals depicted).[154][155] Artists could choose to portray isolated animals or more complex figurative scenes with narrative purposes and more elaborate messages.[156] This approach reached its peak in the narrative and more naturalistic (often entirely "secular") scenes of Neo-Assyrian bas-reliefs,[157] though it was abandoned in other parts of the Middle East, such as Anatolia.[158] The purposes of artistic animal representations are not always easy to determine, but it is clear that they reflect the symbolic functions animals held for both creators and viewers. Therefore, the artists' primary intention was not to depict animals realistically in their natural habitat or purely for aesthetic purposes. Many animal representations are linked to their role as divine symbols or representations of supernatural forces. In these cases, the choice to depict a specific animal likely aimed to imbue the object with some of that creature's power.[159] Symbolic animals are found in Anatolian art across various periods,[160] in the numerous depictions of snakes in Iran—where this animal holds significant symbolic value[161]—and on Babylonian kudurrus (boundary stones) from the second half of the 2nd millennium BCE, which systematically feature divine symbols.[162] This symbolic representation of animals is seen throughout the ancient Middle East. Animal figures on standards and zoomorphic vessels in Anatolia at the end of the 3rd millennium and the beginning of the 2nd millennium BCE had cultic purposes, likely linked to animals' roles as representations of gods or natural forces. Ritual texts reveal that these representations were integrated into worship and could be honored with offerings and libations.[163][164] Animal depictions could also symbolize power. In the Neo-Assyrian Empire, for instance, the lion and the bull represented the king, while the scorpion symbolized the queen and the royal harem.[165] Animal representations also served protective (apotropaic) and healing roles: talismans, amulets, guardian beasts at gates,[166] the "bronze serpents" of ancient Israel,[129] and dog figurines dedicated to the healing goddess Gula (of whom dogs were symbols) in Mesopotamia. These symbolic animal representations typically featured creatures most associated with divine forces: primarily lions and bulls, but also snakes and various mythical creatures ("sphinxes", "griffins", and "winged bulls"). Monumental statues of winged, human-headed bulls and lions—known as šēdu and lamassu—guarded the entrances of Assyrian palace capitals and certain internal passageways. These figures were believed to possess mystical power (puluhtu) that would terrify malevolent forces and provide magical protection for the structure.  In more complex scenes, animals were depicted interacting directly with humans, reflecting societal and political concepts. Numerous scenes show men (kings or mythological heroes) mastering or killing animals in combat and hunting scenarios, from the "Master of Animals" motif on prehistoric Iranian seals[167] to Neo-Assyrian and Persian kings hunting wild animals on orthostats and cylinder seals. Other scenes, common during the Uruk period, depict rulers or warriors feeding or leading animals.[168][125] These images emphasized the sovereign figure's ability to dominate and organize the animal world, reflecting the recurring image of the king as a "shepherd" guiding his people, likened to a flock. The animals depicted here are diverse: wild animals, sometimes mythical ones, and domestic animals (especially caprines and bovines). Additionally, animals appear in scenes where they lack a central symbolic role but serve as auxiliaries or elements enhancing human valor. For example, warriors on chariots pulled by galloping horses evoke martial symbolism.[110] A unique type of narrative scene is common in the Elamite world, particularly on proto-Elamite cylinder seals, depicting animals performing human activities (musicians, builders, or dominating other animals).[169] Ultimately, a limited variety of animals dominate artistic representation, primarily wild animals: the prominent bull-lion pair most associated with sovereign functions (especially in the Syro-Anatolian world), caprines, snakes across all regions, and deer in Anatolia, where they are linked to significant deities. Equines (especially horses, though typically as human auxiliaries) also appear frequently, along with birds and fish (though these never hold a central role). Conversely, animals like sheep (despite likely being the most numerous domestic mammals) and pigs are rarely depicted.[170] Classifications and StereotypesThe scribes of Mesopotamia, followed by those of several other ancient Near Eastern peoples, had the habit of composing extensive lexical lists cataloging and organizing the elements of the known world. These lists offer insights into how the Ancients perceived and classified the animal world. The most extensive of the Mesopotamian lists, named after its incipit HAR.RA = hubullu, in its standard form dating from the 1st millennium BC, gathers names from the animal world, divided into three groups: land animals, air animals, and water animals. The first group is further divided into domestic animals—by far the most thoroughly detailed—and non-domestic ones. In reality, it is more accurate to refer to them as “productive” and “non-productive” animals since dogs and pigs are categorized in the latter group. However, the Ancient Mesopotamians acknowledged the existence of wild animals, generally referred to as būl ṣēri or umām ṣēri, meaning "animals of the steppe", or animals from other environments such as marshes or mountains.[171] In the only discovered Hittite lexical list classifying animals, a similar distinction is made between domestic animals (šupalla-) and wild ones. The wild animals are further divided into field animals (gimraš huitar-, mainly mammals), land animals (daganzipaš huitar-, mostly insects), and sea animals (arunaš huitar-), which includes all water-associated creatures such as frogs and snakes, alongside fish.[172] Pigs and dogs are also placed in a separate category here. In the Hebrew Bible, a form of animal classification appears in the book of Leviticus, which prescribes dietary prohibitions. This classification is primarily based on the distinction between animals that can be eaten and those that cannot, but it also follows other organizational principles. The distinction between domestic and wild animals is evident, as domestic animals (sheep, goats, and cattle) are part of the Covenant between God and humans and can be offered as sacrifices, while wild animals cannot. Classification criteria also include habitat, similar to Mesopotamian and Hittite texts—land, water, and air—but also rely on the animals' physical characteristics for more detailed groupings. For instance, among land animals, which are the most frequently mentioned, quadrupeds are distinguished from others. Then, ruminants or non-ruminants with split hooves are separated from those with solid hooves. Following this, animals that walk on the soles of their feet (plantigrades: lion, dog, hyena, civet) are distinguished from those that crawl on their bellies (creatures like the mole, mouse, and lizard). The classification of air and water animals is less detailed and resembles more of a list.[173] In the mental representations of ancient Near Eastern inhabitants, the divide between wild and domestic animals was deeply significant. Wild animals often symbolized the uncivilized world and, in a sense, chaos, as they lived in the steppe, far from cities, which were seen as the bastions of civilization. This concept is evident in the Epic of Gilgamesh, particularly in the character of Enkidu, a "wild man" who initially lives among animals before being "tamed" by a courtesan and integrating into civilization.[174] Balancing this negative portrayal, wild animals were also considered superior in strength and character compared to domestic animals. Consequently, when people wished to compliment someone, they would compare them to wild animals—rarely to domesticated ones.

Reflections on the status and specificities of animals also appear in tablets of Mesopotamian wisdom literature, which portray various animal species and assign them stereotypical behaviors. These sources include collections of proverbs and even short fables, many of which date back to the Sumerian period, though examples are also known from later periods (and from passages in the Bible).[177] These texts aim to impart moral lessons to humans and may have been written for didactic purposes. They feature a limited number of animals, primarily domestic or those familiar to humans, predominantly mammals, which are closer in behavior and form to humans. Several stereotypes attributed to certain animals by the ancient Mesopotamians can be identified:[1]

These animals are often depicted as characters endowed with the ability to speak, engaging in dialogue with one another and even with humans in mythological texts or other narratives.[180][181] This is less common in Hittite literature, where animals are less personified and rarely appear. One exception is the Myth of Telipinu, where the missing god is sought by an eagle and a bee sent by the gods.[182] Animalized Humans Various texts depict humans being compared to animals. In the Amarna Letters, for example, the vassal kings of the Egyptian pharaoh frequently use the image of the dog: often as a means to insult an enemy, with "dog" serving as a derogatory term; but conversely, a vassal might present himself as the loyal dog of his master. The Assyrian royal annals also make recurrent use of similar comparisons in passages describing the king's victories. The king is often portrayed as a lion (a common association in Mesopotamia since the Akkadian period)[183] and also as a wild bull; in the mountains, he is likened to an agile mouflon. He is consistently represented as a wild animal. When the enemy takes on the traits of a domestic animal, it might be a lamb, like those sacrificed to the gods, or a donkey. When depicted as a wild animal, the enemy is associated with creatures perceived as cowardly or deceitful, such as the fox or the bear, quick to flee before the power of the Assyrian king.[184] Similar imagery is used in older letters and chronicles from the reign of the Hittite king Hattusili I, dating back a millennium earlier. The lion and the eagle are the quintessential animals symbolizing the king, while enemies are represented as wolves (symbolizing chaos and the rejection of established order) and foxes (representing cowardice), among others.[185] In a more peaceful context, the royal ideology of the ancient Near East also emphasizes the figure of the shepherd-king, where the king’s subjects are likened to a flock.[186] These animal metaphors are also present in biblical texts. In these documents, animalization also occurs through personal names linked to animals, which are relatively common. Such names may have been given to confer animal vitality and strength upon their bearers or to honor deities associated with those animals. For boys, these names are often connected to strength, speed, or skill, while for girls they typically emphasize elegance or fertility. However, these name attributions often remain quite enigmatic, as seen in the cases of Rebecca (Rivqah) meaning "Cow", Rachel (Rakkel) meaning "Ewe", Deborah meaning "Bee", and Jonah (Yonah) meaning "Dove."[187] Individuals bearing animal-related names are also found in other contexts, such as in documents from Ugarit[188] or Mari.[189] Taboos in Human/Animal Relationships: Dietary Prohibitions and BestialityThe classification of animals into various categories can also result in interactions with certain species being relegated to the realm of taboo. This is particularly evident in the dietary prohibitions found in the Bible, especially in Deuteronomy and Leviticus, which identify a range of impure animals that cannot be consumed. These include pigs, birds of prey, camels, scavengers, aquatic creatures without scales and fins, most winged insects, certain creeping creatures, and others. A general prohibition concerns the consumption of blood and animals that have not been properly drained of blood, as they are considered impure. Other specific bans include the commandment forbidding the cooking of a young goat in its mother’s milk.[190][191][192]

One case has been particularly studied: that of pigs and the suidae family in general. Domesticated alongside other domestic animals since the 9th millennium BC, solely for food consumption, pigs are often depicted in iconography, as are wild boars, which were hunted. From the end of the 2nd millennium BC, pigs mentioned in Babylonian omen texts are always harbingers of bad news. Gradually, these animals came to be seen as impure and even foolish. In the southern Levant, pigs seem to have disappeared during the second half of the 2nd millennium BC, as there is no trace of them in archaeological sites. The Hebrew Bible ultimately forbids the consumption of this animal (Leviticus 11 and Deuteronomy 14): this prohibition is religious and part of a broader set of rules specifying which animals can and cannot be eaten. Although pigs were still present in Mesopotamia during the Neo-Assyrian period (911–609 BC), they disappeared from Mesopotamian records in the Neo-Babylonian period (624–539 BC). This phenomenon remains poorly understood. In the case of the Hebrews, this may have been a way to distinguish themselves from neighboring enemy peoples, notably the Philistines, who consumed large quantities of pork. Pigs have always occupied a unique position among domesticated animals because they are the only ones that are not productive (e.g., providing milk, wool, or labor) and are raised solely for their meat.[193][194] Among the religious prohibitions related to animals is also the case of bestiality, which appears in the Hebrew Bible (Exodus 22:18 and Leviticus 18:23) and in two passages of the Hittite Laws, though certain ambiguities remain. A man guilty of sexual relations with a pig, sheep, or dog could be punished by death unless pardoned by the king. However, the death penalty was exceptional in Hittite law (even homicide was typically punished with a fine), suggesting that the sin of zoophilia was considered extremely severe in these cases. Conversely, sexual relations with a horse or donkey did not warrant the death penalty, likely because these animals were held in higher regard. In any case, a man who committed an act of zoophilia was deemed impure, as he could no longer appear before the king without risking contaminating him.[195] See alsoRelated articlesExternal links

References

BibliographyWork tools

Animal studies

|

Portal di Ensiklopedia Dunia