|

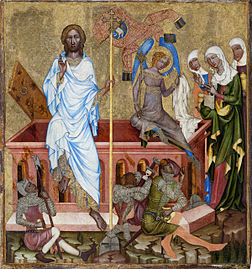

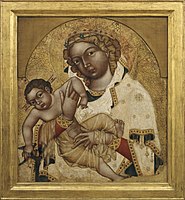

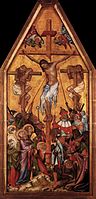

Vyšší Brod (Hohenfurth) cycleThe Vyšší Brod (Hohenfurth) cycle, (also known as Hohenfurth altarpiece) ranks among the most important monuments of European Gothic painting.[1][2] It is made up of nine panel paintings depicting scenes from the Life of Christ, covering his childhood, Passion and resurrection. These paintings were made between 1345 and 1350 in the workshop of the Master of Vyšší Brod that was most probably based in Prague. The pictures were either meant for a square altar retable[3] or else they decorated the choir partition of the church of the Cistercian Abbey in Vyšší Brod. The work was evidently commissioned by Petr I of Rosenberg, Supreme Chamberlain of the Bohemian Kingdom, who financed the abbey.[4] This series of paintings is a rare example of a complete Gothic altar retable (although there is not complete agreement on the fact that it was a retable, in other words a structure standing on the altar – there have also been theories that it could have been hung on the choir pews or rood screen. Having been returned to its former owner, the Cistercian Abbey in Vyšší Brod, it is being exhibited as a long-term loan in the permanent exhibition of the Collection of Medieval Art of the National Gallery in Prague. According to Hana Hlaváčková, the entire cycle could have been made for the coronation of Charles IV (1347) in St. Vitus Cathedral, which was unfinished at the time and the paintings could have covered the ongoing construction work. The author believes that the paintings were hung in a row between the choir and the nave behind the altar of the Holy Cross. This is evidenced by the damage from the candle flame, which the restorers found only on the central triptych.[5] There is no mention of the paintings in the documents of the monastery in Vyšší Brod, and there is no suitable place for the entire cycle in the church there.[6][7] Therefore, some researchers believe that the Hohenfurth cycle was moved there only secondarily.[8] DescriptionThe panels’ dimensions are approximately 99 x 92 cm in size. Each of them is composed of three sycamore boards 2 cm thick that are joined with pegs and covered with linen canvas. The underdrawing on the chalk base was executed in charcoal and engraving. The painting was executed in tempera and pigments were bonded with gelatine. A dark purple poliment forms the base of the gilding; orange-yellow poliment underlies the silver foil. Especially in layering up the flesh tones, the Master of the Vyšší Brod Altarpiece used a complex system of layers and underpainting that was based in the Byzantine painting tradition and does not, therefore, have any parallels in Central European painting of that time. The identical painting technique on all the panels confirms that they were produced in a single workshop.[9] Although there could be a mutual exchange of motifs, materials and individual artists with manuscript illuminators, the workshop focused on panel paintings and murals operated independently.[10] The series features trios of connected scenes from the Christological cycle that are arranged so that the central one is that of the Crucifixion. They are designed for believers to meditate on and are related to the most important church festivals.[11] A series of motifs that the Master of the Vyšší Brod Altarpiece used for the first time in Bohemian painting conceals symbols relating to the Gospels, as well as to the Apocrypha and medieval theological texts (The Song of Songs and texts by St Bernard of Clairvaux). The bottom rowThe bottom row of paintings represents scenes from the childhood of Christ and relates to Advent (specifically the Annunciation of the spring festival on 25 March) and Christmas festivals. It is characterised by a radiant palette and light colour tones combined with gold. The Annunciation to the Virgin Mary The Angel of the Annunciation comes to the Virgin Mary, who holds an open book in her hand. The band of the inscription reads Ave gracia plena d(omi)n(u)s tecu(m). The scene is accompanied by the customary symbols – a lily and Mary holding a veil (virginity), an open book (conception) and peacocks (immortality and eternity). A series of other symbols provides various interpretations (God sending dew from heaven or manna in the desert;[12] a coffer of money). Mary on her throne thus represents the Virgin of the Temple of God protecting the Ark of the Covenant or else the Queen of Heaven,[13] the throne also being her bed chamber. Her crown’s garland of nine stars could be an astrologically-related depiction of the constellation of Virgo.[14] A less evident symbol is the motif of a tree with a small double trunk in the left-hand part which refers to the trees of life and knowledge in paradise as well as to the double incarnation of Christ as God and man. A notable secular feature of scene is that of the rich garment worn by the angel who comes across more like a courtier bringing the ruler’s insignia (an imperial orb). The motif of the lily on a blue background that appears on the angel’s cloak originate in France and refers to the heraldry of the French rulers of the House of Valois. Mary is portrayed not as a simple maiden but as a monarch on the throne with a crown on her head. The scene as a whole could be connected with the coronation of Charles IV and Blanche of Valois as King and Queen of Bohemia at Prague Castle on 2 September 1347.[14] The Nativity of Jesus This picture connects three scenes. The central scene is that of Mary with the infant Christ in a simple, open shelter. She is accompanied in the background by the customary apocryphal animals. In the foreground, Joseph is preparing a bath with the midwife (called Salome in the Apocrypha) and in the background the archangel Gabriel is announcing the good tidings to the shepherds (the Annunciation to the Shepherds scene). The active involvement of Joseph as a foster father in the events of the scene, specifically in the active care for the new-born baby, is relatively unusual in the first half of the 14th century although it does appear as early as the 13th century. However it appears more often from the turn of the 14th century (for example with Joseph cooking porridge, preparing a bath, sewing and drying nappies, preparing food for Mary and feeding the donkey and ox). It is not based in any literary sources and, in all likelihood, originated in the secular context of burgher society; we can also trace how it was received and reflected on in period ‘carols’ that, however, represent the foster father of Our Lord as a rather grotesque figure. At the same time, from the 14th and 15th centuries onwards, official respect for St Joseph grew. In all the scenes there is a multitude of small motifs that have their origin in Byzantine art mediated, or rather interpreted, by Italian masters. Mary is reclining on a bed and kisses the infant on his lips in a manner that is connected with her mystic role as Christ’s bride in the Song of Songs in which Mary is the personification of the Christian Church. The child’s nudity refers to his humanity and relates to efforts to humanise a religious theme that was propagated by the Franciscan Order.[15] The bed is spread with a finely decorated cover symbolising Mary as the Queen of Heaven. In the bottom right-hand corner there kneels a donor whom the crest with its five-petalled rose identifies as member of the House of Rosenberg. In his hand he is holding the model of a church – in all likelihood it is the abbey church at Vyšší Brod. The band above the crest has never been inscribed. The Adoration of the Magi This scene repeats the analogous composition of the throne as it appears in the painting of the Annunciation and the customary model that was maintained during the 14th century, one in which kings or wise men represented three ages of man and the second king, of a virile age, sometimes takes the form of the ruling monarch. It was only from the 1360s (or, more likely, from the early 15th century, because the black king in the Emmaus monastery painting was evidently a piece of Baroque overpainting) that the kings were more frequently portrayed as representatives of the three continents known at that time. In this scene as well, Mary remains a queen seated on a throne. The motif of an old man kissing the hand of a small child, one that was rare outside France until then, is the expression of a spiritual bond with Christ and originates in the work Meditationes Vitae Christi that appeared in Bohemia during the reign of Charles IV, Holy Roman Emperor. The throne is depicted in an imperfect empirical perspective. The Virgin Mary, obscuring one of the supporting pillars of the canopy, is symbolically presented as a pillar of the Christian Church. The centreThe central paintings are related to the Christian holidays of Easter with the martyrdom and resurrection of Christ. This is reflected in the darker tones in larger areas and in the limiting of decoration. Christ on the Mount of OlivesThe main element of the composition is formed by the diagonal of the mount’s slope with jagged rock faces and blossoming spring vegetation. The picture represents a traditional iconographic arrangement with the praying Christ and three sleeping apostles: St Peter, St John and St James. Three accurately portrayed birds (a goldfinch, bullfinch and crested lark or hoopoe) evidently originate in English or French book painting. The goldfinch is often associated with the martyrdom of Christ, because it feeds on the seeds of thistles and metaphorically represents Christ’s crown of thorns. In medieval legend, the bullfinch is associated with the Crucifixion and its red breast with drops of Christ’s blood refers to the moment the bullfinch pulled out a nail from the cross with its beak.[16] The crested lark could, in earlier literature, be associated with the martyrdom of Christ.[17] The CrucifixionThe type of Crucifixion with a single cross and a group of figures is customary for the 13th century. Several motifs, such as the fainting Mary, Mary Magdalene embracing the cross and flying angels with incense burners, originate in the Italian context. The figures beneath the cross include St Longinus with a spear, Joseph of Arimathea, possibly also Nicodemus and the ‘good’ centurion leaning on his shield decorated with a human face (the ‘gorgoneion’). This figure appears in the Bohemian context between the mid-14th century and the mid-15th century. It originally had an apotropaic function and could symbolically represent the opposites of Christ and the devil, the sun and the moon; and Christianity and paganism.[18] In the work of the Master of the Vyšší Brod Altarpiece, Eucharistic motifs linked with Christ’s wounds are emphasised. They include Mary’s cloak spattered with Christ’s blood and Longinus miraculously cured of his blindness by blood from Christ’s side. The symbolism could be directly influenced by the courtly environment of Charles IV, who kept part of Mary’s bloodied robe and the tip of St Longinus’s spear as holy relics. The Lamentation The Crucifixion is usually followed by the scene of the Descent from the Cross and the Entombment. The Lamentation, which is not mentioned in the Gospels, is usually missing from older depictions.[19] Until the 14th century, the Lamentation was part of the scene of the Entombment and only appears separately in the Meditationes Vitae Christi and in Giotto’s fresco in the Scrovegni Chapel. In the picture that, with the locating of the cross in the centre of the composition, refers back to the preceding Crucifixion, the strikingly independent Mary with Christ in her lap is an innovation made by the Master of the Vyšší Brod. This portrayal anticipates a whole series of early ‘vertical’ Pietàs and evidently also inspired Bohemian Gothic sculpture. Mary is just about to kiss Jesus and here, as Our Lady of Sorrows, is once again a mother cradling her child in her lap. The other figures originate in older, tradition depictions: St John, St Mary Magdalene, the two Marys – relatives of the Virgin Mary (half-sisters of the Virgin Mary, Mary Cleophas and Mary Salome), Nicodemus and a pair of angels holding incense burners. Joseph of Arimathea is also present. The top row The ResurrectionThis picture combines two events – the Resurrection of Jesus and the Three Marys by the tomb – which follow on from each other and whose joint presentation was rare in earlier painting. The main scene was originally the Visitation – a depiction of three Marys by the empty tomb, where an angel appeared and told them of Christ’s resurrection (the Gospels of St Mark and St Matthew). The resurrection of Christ is the most important Christian holiday, despite the fact that the Gospels don’t mention the scene itself. It was only from the 12th and 13th centuries onwards that Christ was portrayed emerging from the sarcophagus and, later, standing on the sealed sarcophagus along with surprised soldiers who are guarding it. The miraculous Resurrection, invisible to witnesses, is the dominant scene. This is reinforced by the figure of Christ being on a larger scale. The Resurrection is conceived as the triumph over death and its symbol is the banner of Christ, whose pole recalls the wood of the cross while the banner bearing the image of a lamb recalls Christ’s sacrifice. Despite using the customary gilded background, the composition of the picture features spatial depth.  The final two pictures relate to stories of the Ascension of Christ and the sending down of the Holy Spirit, which Christians celebrate as Pentecost. These mysterious and supernatural events are accompanied by a more vivid and contrasting colour palette. The AscensionThe Ascension of the Lord is one of the central dogmas of Christianity (The Deeds of the Apostles) and is celebrated ten days before Pentecost. It followed forty days after his Resurrection, when he appeared to Mary Magdalene and finally also to the apostles before God took him up to heaven. In earlier depictions this scene shows Christ in a mandorla borne by angels. Here, the painter deals with them in a conventional way and only depicts Christ’s lower legs as he ascends into the clouds. The symmetrical composition features in its background a green landscape with Christ’s footprints. The apostles, whose figures the painter differentiated by the gestures of their hands, are mostly old men. Descent of the Holy Spirit At the centre of the Pentecost scene, which in Byzantine painting usually featured St Peter and St Paul, the Virgin Mary sits with an open book. The twelve apostles, upon whom the Holy Spirit descended in the form of tongues as of fire, were endowed with the gift of mastering the languages of all nations so they could spread the gospel. The motif of the apostle who is placing his finger to his mouth as a symbol of silence was adopted from Italian art, in which it represents an allegory of obedience or patience.[20] The specific involvement of the painter and his collaboratorsThe entire series is chiefly the work of the Master of the Vyšší Brod Altarpiece, who has a distinctive painting style. He painted the Annunciation, the Birth of Christ, the Adoration of the Magi, the Mount of Olives and the Resurrection. His figures are substantial; they stand firmly on the ground and their movement and poses are depicted in a believable way. The modelling of the drapery describes volume as well as the proportions, mechanics and position of the body. The nude body of the child respects the basic proportions of the body.[21] The figures’ gestures are measured and justified by the action of the given situation. Their faces have physiological features that also distinguish them from each other. Apart from the master in charge, it is probable that three other painters worked on the series as a whole – the first two were a young and able collaborator and a capable but stylistically inconsistent collaborator who painted the panel depicting the Sending Down of the Holy Spirit. In terms of painting technique, the weakest work of the series is the Ascension which, however, also displays several highly developed features such as a greater individualisation of the faces.[22] The panels have been impacted by overpainting and have also been repeatedly restored, most recently in 1993-2007.[23] Selected details

Iconography and classification The pictures of the Vyšší Brod Master are a synthesis of the Italianate style, whose strikingly Byzantine features reached Bohemia from the region of Venice in particular, and of the Western European Gothic drawing-based style that originated in France. Earlier works that could have inspired its painters include book illustrations (Jean Pucelle, Bolognese illuminators active in St Florian), murals (the choir of the cathedral in Cologne), panel painting (Meister der Rückseite des Verduner Altars) and sculpture (the Master of the Michle Madonna). Several works created by other artists (Antependium of Königsfelden,[24] Kaufmann Crucifixion) have motifs that are so similar that it can be speculated that they used the same models. The iconographic conception that, in groups of works, depicts the most important moments in the life of Christ, is based in cycles by the leading painters of the Italian Trecento – Giotto and Duccio. The stylised crystalline terrain representing rock faces is typical of the 1340s. Italian influences manifest themselves especially in the painting technique, the retreat of the drawing-based approach and a greater plasticity of the figures, decorative patterns, the typology of the heads and the more highly developed depiction of the landscape and architecture. The affinity between the painting of the Vyšší Brod Master and the artistic and spiritual climate of Venice, represented by his contemporary Paolo Veneziano, is especially striking. Influence on Bohemian and European paintingSeveral motifs of the Vyšší Brod series were subsequently adopted by Bohemian book painting, in particular Velislai biblia picta (before 1349) and the Legend of St Hedwig,[25] Liber viaticus by John of Neumarkt (1350-1364) and the Missal of John of Neumarkt. In panel painting, it was followed on from by the painter of Morgan panels[26] and, in a broader circle, the altar at Tirol Castle, the Westphalian Master Bertram (Grabow Altarpiece), the painter who created the Toruń Altarpiece[27] and the altarpiece of Erfurt by Meister des Erfurter Einhornaltars. The motif of Mary’s bloodied robe is connected almost exclusively with the Bohemian context and appears in the work of the Master of the Třeboň Altarpiece, the Master of the Rajhrad Altarpiece and persisted until the mid-15th century. History of the artworkAlthough few works of art survive from the reign of John of Luxembourg (1296-1346) (Passional of Abbess Kunigunde, 1312-1321, Kaufmann Crucifixion, after 1330),[28] it is clear that there was already an important centre in Prague where French and Italian painting influences were mixed.[29] Other important artists (Master Theodoric, Master of the Luxembourg Genealogy) were commissioned to decorate Karlštejn Castle.[30] The altarpiece was probably made for St. Vitus Cathedral and the coronation of Charles IV,[8] rather than for Cistercian Abbey in Vyšší Brod. Its donor was in all likelihood Petr I of Rosenberg, the Supreme Royal Chamberlain, Supreme Judge and executor of John of Luxemburg’s will. The donor’s personal reason could have been to intercede for the salvation of the soul of his son, who died alongside John of Luxemburg at the Battle of Crécy. Petr of Rosenberg supported Vyšší Brod Abbey from 1332. Before his death on 14 October 1347 he received the Cistercian robe and was buried in the monastery. Jošt of Rosenberg, Petr’s son and inheritor of his function as Royal Chamberlain, subsequently had the altarpiece completed. The paintings were made in the Prague court workshop.[citation needed] In 1938, before the outbreak of the Second World War, the altarpiece was transferred to the Picture Gallery (the Collection of Old Art of what would later become the National Gallery in Prague). During the war, however, it was stolen by the Nazis and stored in the Vyšší Brod Abbey along with other works. Hitler intended to place them in the planned Imperial Museum in Linz, Upper Austria. At the end of the war, the altarpiece was discovered by the American army in a salt mine in Bad-Aussee, Austria, along with other artworks. It was transported to Munich and in 1947 was returned to the National Gallery.[31] In 2014 it was returned as part of restitution to the Cistercian Abbey in Vyšší Brod and is now on long-term loan to the Prague National Gallery.[citation needed] Related works

Notes

Sources

External links |

Portal di Ensiklopedia Dunia