|

Vikramaditya Empire

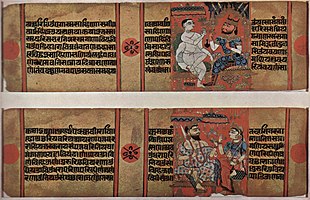

The Vikramaditya Empire or Paramāri kingdom is a mythical empire linked with the legendary king of Ujjain, Vikramaditya. Most historians consider the empire as a folklore construct, but few of them associate the empire with the Paramara dynasty, especially under the rule of Bhoja, as Vikramaditya and Bhoja are sometimes interlinked with each other.[1][citation needed] In Hindu texts After the ninth century, a calendar era beginning in 57 BCE (now called the Vikrama Samvat) began to be associated with Vikramaditya; some legends also associate the Shaka era (beginning in 78 CE) with him. A Hindu text called Bhavisya Purana tells that,The Paramara dynasty originated from Pramara, born from a fire pit at Mount Abu. Vikramaditya, a descendant of Pramara, was sent by Shiva to earth to restore Vedic faiths. Vikramaditya's empire expanded through a horse sacrifice, defining its boundaries from the Indus River to Rameswaram. He united four Agnivanshi clans by marrying princesses from rival clans, earning celebration from all gods except Chandra.[2] History

The Vikram Samvat era, beginning in 57 BCE, was not associated with Vikramaditya until the 9th century CE. Earlier sources referred to the era as "Kṛṭa" (343 and 371 CE), "Kritaa" (404), or "the era of the Malava tribe" (424).[4] The first known inscription linking the era to Vikramaditya dates back to 971 CE. Bhavisya Purana also deals with a claim, which says that Vikramaditya ruled Malwa — which includes parts of present-day western Madhya Pradesh and southeastern Rajasthan — from 57BC and Ujjain was his capital.[5] AdministrationLegends attribute various reforms to Vikramaditya, including the promotion of justice, protection of women's rights, aid for the poor, and advancements in education. However, the historical accuracy of these claims remains debated.[6] Imperial history According to Bhavishya Purana, The empire of king Vikramaditya was divided into 18 kingdoms each having their own administers. The legends, says that king Vikramaditya patronized art and literature. The peoples also enjoyed a great level of political and cultural prestige under the Paramāris. The Paramāris were well known for their patronage to Sanskrit poets and scholars, and Vikramaditya was himself a renowned scholar. Although he was a Shaivite, he also patronized Jain scholars. The Chinese monk Xuanzang wrote in his book Si-yu-ki that Vikramaditya, was the king of Shravasti rejecting the Ujjain claim, and was known for his generosity. Vikramaditya gave away large sums of gold coins to the poor and to individuals in need. A Buddhist monk named Manoratha was humiliated by the king and non-Buddhist scholars after winning a debate. Before dying, Manoratha advised his disciple Vasubandhu to avoid debating ignorant people. After Vikramaditya's death, Vasubandhu avenged his mentor's humiliation by defeating 100 non-Buddhist scholars in a debate.[7][8] According to 4th century author Kalidasa, says that Vikramaditya conquered 21 kingdoms and made Prayag as his capital [citation needed]. Vikramaditya expanded his realm westwards, defeating the Saka Western Kshatrapas of Malwa, Gujarat and Saurashtra in a campaign lasting until 409. This extended his control from coast to coast, established a second capital at Ujjain and was the high point of the empire.[citation needed] Kuntala inscriptions indicate rule of Vikramaditya in Kuntala country of Karnataka.[9] Hunza inscription also indicate that he was able to rule north western Indian subcontinent and proceeded to conquer Balkh, although some scholars have also disputed the identity of the emperor.[10][11]. One of the sources tells that Vikramaditya issued Gadhiya coins and Dinars. Locally Cowries, were also in used for small businesses and trading.[citation needed] DeclineAccording to Ananta's[disambiguation needed] 12th-century heroic poem, Vira-Charitra (or Viracharita), Shalivahana (or Satavahana) defeated and killed Vikramaditya and ruled from Pratishthana. Shalivahana's associate, Shudraka, later allied with Vikramaditya's successors and defeated Shalivahana's descendants. This legend contains a number of mythological stories.[12][13] See alsoReferences

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Portal di Ensiklopedia Dunia