|

Use case

In software and systems engineering, the phrase use case is a polyseme with two senses:

This article discusses the latter sense. (For more on the other sense, see for example user persona.) A use case is a list of actions or event steps typically defining the interactions between a role (known in the Unified Modeling Language (UML) as an actor) and a system to achieve a goal. The actor can be a human or another external system. In systems engineering, use cases are used at a higher level than within software engineering, often representing missions or stakeholder goals. The detailed requirements may then be captured in the Systems Modeling Language (SysML) or as contractual statements. HistoryIn 1987, Ivar Jacobson presented the first article on use cases at the OOPSLA'87 conference.[1] He described how this technique was used at Ericsson to capture and specify requirements of a system using textual, structural, and visual modeling techniques to drive object-oriented analysis and design.[2] Originally he had used the terms usage scenarios and usage case – the latter a direct translation of his Swedish term användningsfall – but found that neither of these terms sounded natural in English, and eventually he settled on use case.[3] In 1992 he co-authored the book Object-Oriented Software Engineering - A Use Case Driven Approach,[4] which laid the foundation of the OOSE system engineering method and helped to popularize use cases for capturing functional requirements, especially in software development. In 1994 he published a book about use cases and object-oriented techniques applied to business models and business process reengineering.[5] At the same time, Grady Booch and James Rumbaugh worked at unifying their object-oriented analysis and design methods, the Booch method and Object Modeling Technique (OMT) respectively. In 1995 Ivar Jacobson joined them and together they created the Unified Modelling Language (UML), which includes use case modeling. UML was standardized by the Object Management Group (OMG) in 1997.[6] Jacobson, Booch and Rumbaugh also worked on a refinement of the Objectory software development process. The resulting Unified Process was published in 1999 and promoted a use case driven approach.[7] Since then, many authors have contributed to the development of the technique, notably: Larry Constantine developed in 1995, in the context of usage-centered design, so called "essential use-cases" that aim to describe user intents rather than sequences of actions or scenarios which might constrain or bias the design of user interface;[8] Alistair Cockburn published in 2000 a goal-oriented use case practice based on text narratives and tabular specifications;[9] Kurt Bittner and Ian Spence developed in 2002 advanced practices for analyzing functional requirements with use cases;[10] Dean Leffingwell and Don Widrig proposed to apply use cases to change management and stakeholder communication activities;[11] Gunnar Overgaard proposed in 2004 to extend the principles of design patterns to use cases.[12] In 2011, Jacobson published with Ian Spence and Kurt Bittner the ebook Use Case 2.0 to adapt the technique to an agile context, enriching it with incremental use case "slices", and promoting its use across the full development lifecycle[13] after having presented the renewed approach at the annual IIBA conference.[14][15] General principleUse cases are a technique for capturing, modeling, and specifying the requirements of a system.[10] A use case corresponds to a set of behaviors that the system may perform in interaction with its actors, and which produces an observable result that contributes to its goals. Actors represent the role that human users or other systems have in the interaction. In the requirement analysis, at their identification, a use case is named according to the specific user goal that it represents for its primary actor. The case is further detailed with a textual description or with additional graphical models that explain the general sequence of activities and events, as well as variants such as special conditions, exceptions, or error situations. According to the Software Engineering Body of Knowledge (SWEBOK),[16] use cases belong to the scenario-based requirement elicitation techniques, as well as the model-based analysis, techniques. But the use cases also support narrative-based requirement gathering, incremental requirement acquisition, system documentation, and acceptance testing.[1] VariationsThere are different kinds of use cases and variations in the technique:

ScopeThe scope of a use case can be defined by a subject and by goals:

UsageUse cases are known to be applied in the following contexts:

TemplatesThere are many ways to write a use case in the text, from use case brief, casual, outline, to fully dressed etc., and with varied templates. Writing use cases in templates devised by various vendors or experts is a common industry practice to get high-quality functional system requirements. Cockburn styleThe template defined by Alistair Cockburn in his book Writing Effective Use Cases has been one of the most widely used writing styles of use cases.[citation needed] Design scopesCockburn suggests annotating each use case with a symbol to show the "Design Scope", which may be black-box (internal detail is hidden) or white box (internal detail is shown). Five symbols are available:[20] Other authors sometimes call use cases at the Organization level "Business use cases".[21] Goal levels Cockburn suggests annotating each use case with a symbol to show the "Goal Level";[22] the preferred level is "User-goal" (or colloquially "sea level"[23]: 101 ).

Sometimes in text writing, a use case name followed by an alternative text symbol (! +, -, etc.) is a more concise and convenient way to denote levels, e.g. place an order!, login-. Fully dressedCockburn describes a more detailed structure for a use case but permits it to be simplified when less detail is needed. His fully dressed use case template lists the following fields:[24]

In addition, Cockburn suggests using two devices to indicate the nature of each use case: icons for design scope and goal level. Cockburn's approach has influenced other authors; for example, Alexander and Beus-Dukic generalize Cockburn's "Fully dressed use case" template from software to systems of all kinds, with the following fields differing from Cockburn:[26]

CasualCockburn recognizes that projects may not always need detailed "fully dressed" use cases. He describes a Casual use case with the fields:[24]

Fowler styleMartin Fowler states "There is no standard way to write the content of a use case, and different formats work well in different cases."[23]: 100 He describes "a common style to use" as follows:[23]: 101

The Fowler style can also be viewed as a simplified variant of the Cockburn template. This variant is called a user story. Alistair Cockburn stated:[27]

Martin Fowler stated:[27]

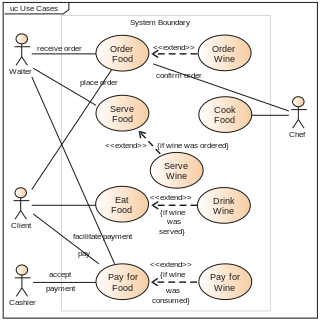

ActorsA use case defines the interactions between external actors and the system under consideration to accomplish a goal. Actors must be able to make decisions, but need not be human: "An actor might be a person, a company or organization, a computer program, or a computer system—hardware, software, or both."[28] Actors are always stakeholders, but not all stakeholders are actors, since they may "never interact directly with the system, even though they have the right to care how the system behaves."[28] For example, "the owners of the system, the company's board of directors, and regulatory bodies such as the Internal Revenue Service and the Department of Insurance" could all be stakeholders but are unlikely to be actors.[28] Similarly, a person using a system may be represented as a different actor because of playing different roles. For example, user "Joe" could be playing the role of a Customer when using an Automated Teller Machine to withdraw cash from his own account or playing the role of a Bank Teller when using the system to restock the cash drawer on behalf of the bank. Actors are often working on behalf of someone else. Cockburn writes that "These days I write 'sales rep for the customer' or 'clerk for the marketing department' to capture that the user of the system is acting for someone else." This tells the project that the "user interface and security clearances" should be designed for the sales rep and clerk, but that the customer and marketing department are the roles concerned about the results.[29] A stakeholder may play both an active and an inactive role: for example, a Consumer is both a "mass-market purchaser" (not interacting with the system) and a User (an actor, actively interacting with the purchased product).[30] In turn, a User is both a "normal operator" (an actor using the system for its intended purpose) and a "functional beneficiary" (a stakeholder who benefits from the use of the system).[30] For example, when user "Joe" withdraws cash from his account, he is operating the Automated Teller Machine and obtaining a result on his own behalf. Cockburn advises looking for actors among the stakeholders of a system, the primary and supporting (secondary) actors of a use case, the system under design (SuD) itself, and finally among the "internal actors", namely the components of the system under design.[28] Business use caseIn the same way that a use case describes a series of events and interactions between a user (or other types of Actor) and a system, in order to produce a result of value (goal), a business use case describes the more general interaction between a business system and the users/actors of that system to produce business results of value. The primary difference is that the system considered in a business use case model may contain people in addition to technological systems. These "people in the system" are called business workers. In the example of a restaurant, a decision must be made whether to treat each person as an actor (thus outside the system) or a business worker (inside the system). If a waiter is considered an actor, as shown in the example below, then the restaurant system does not include the waiter, and the model exposes the interaction between the waiter and the restaurant. An alternative would be to consider the waiter as a part of the restaurant system (a business worker) while considering the client to be outside the system (an actor).[31]  Visual modeling

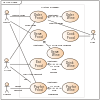

Use cases are not only texts but also diagrams if needed. In the Unified Modeling Language, the relationships between use cases and actors are represented in use case diagrams originally based upon Ivar Jacobson's Objectory notation. SysML uses the same notation at a system block level. In addition, other behavioral UML diagrams such as activity diagrams, sequence diagrams, communication diagrams, and state machine diagrams can also be used to visualize use cases accordingly. Specifically, a System Sequence Diagram (SSD) is a sequence diagram often used to show the interactions between the external actors and the system under design (SuD), usually for visualizing a particular scenario of a use case. Use case analysis usually starts by drawing use case diagrams. For agile development, a requirement model of many UML diagrams depicting use cases plus some textual descriptions, notes, or use case briefs would be very lightweight and just enough for small or easy project use. As good complements to use case texts, the visual diagram representations of use cases are also effective facilitating tools for the better understanding, communication, and design of complex system behavioral requirements. ExamplesBelow is a sample use case written with a slightly modified version of the Cockburn-style template. Note that there are no buttons, controls, forms, or any other UI elements and operations in the basic use case description, where only user goals, subgoals, or intentions are expressed in every step of the basic flow or extensions. This practice makes the requirement specification clearer and maximizes the flexibility of the design and implementation.  Use Case: Edit an article Primary Actor: Member (Registered User) Scope: a Wiki system Level: ! (User goal or sea level) Brief: (equivalent to a user story or an epic)

Stakeholders ... Postconditions

Preconditions:

Triggers:

Basic flow:

Extensions: 2–3.

4a. Timeout: ... AdvantagesSince the inception of the agile movement, the user story technique from Extreme Programming has been so popular that many think it is the only and best solution for the agile requirements of all projects. Alistair Cockburn lists five reasons why he still writes use cases in agile development.[32]

In summary, specifying system requirements in use cases have these apparent benefits compared with traditional or other approaches: User focused Use cases constitute a powerful, user-centric tool for the software requirements specification process.[33] Use case modeling typically starts from identifying key stakeholder roles (actors) interacting with the system, and their goals or objectives the system must fulfill (an outside perspective). These user goals then become the ideal candidates for the names or titles of the use cases which represent the desired functional features or services provided by the system. This user-centered approach ensures that what has real business value and the user really want is developed, not those trivial functions speculated from a developer or system (inside) perspective. Use case authoring has been an important and valuable analysis tool in the domain of User-Centered Design (UCD) for years. Better communication Use cases are often written in natural languages with structured templates. This narrative textual form (legible requirement stories), understandable by almost everyone, and complemented by visual UML diagrams fosters better and deeper communications among all stakeholders, including customers, end-users, developers, testers, and managers. Better communications result in quality requirements and thus quality systems delivered. Quality requirements by structured exploration One of the most powerful things about use cases resides in the formats of the use case templates, especially the main success scenario (basic flow) and the extension scenario fragments (extensions, exceptional and alternative flows). Analyzing a use case step by step from preconditions to postconditions, exploring and investigating every action step of the use case flows, from basic to extensions, to identify those tricky, normally hidden and ignored, seemingly trivial but realistically often costly requirements (as Cockburn mentioned above), is a structured and beneficial way to get clear, stable and quality requirements systematically. Minimizing and optimizing the action steps of a use case to achieve the user goal also contribute to a better interaction design and user experience of the system. Facilitate testing and user documentation With content based upon an action or event flow structure, a model of well-written use cases also serves as excellent groundwork and valuable guidelines for the design of test cases and user manuals of the system or product, which is an effort-worthy investment up-front. There are obvious connections between the flow paths of a use case and its test cases. Deriving functional test cases from a use case through its scenarios (running instances of a use case) is straightforward.[34] LimitationsLimitations of use cases include:

Misconceptions

Common misunderstandings about use cases are: User stories are agile; use cases are not. Agile and Scrum are neutral on requirement techniques. As the Scrum Primer[39] states,

Use case techniques have evolved to take Agile approaches into account by using use case slices to incrementally enrich a use case.[13] Use cases are mainly diagrams. Craig Larman stresses that "use cases are not diagrams, they are text".[40] Use cases have too much UI-related content. As some put it,[who?]

Novice misunderstandings. Each step of a well-written use case should present actor goals or intentions (the essence of functional requirements), and normally it should not contain any user interface details, e.g. naming of labels and buttons, UI operations, etc., which is a bad practice and will unnecessarily complicate the use case writing and limit its implementation. As for capturing requirements for a new system from scratch, use case diagrams plus use case briefs are often used as handy and valuable tools, at least as lightweight as user stories. [citation needed] Writing use cases for large systems is tedious and a waste of time. As some put it,[who?]

Spending much time writing tedious use cases which add no or little value and result in a lot of rework is a bad smell indicating that the writers are not well skilled and have little knowledge of how to write quality use cases both efficiently and effectively. Use cases should be authored in an iterative, incremental, and evolutionary (agile) way. Applying use case templates does not mean that all the fields of a use case template should be used and filled out comprehensively from up-front or during a special dedicated stage, i.e. the requirement phase in the traditional waterfall development model. In fact, the use case formats formulated by those popular template styles, e.g. the RUP's and the Cockburn's (also adopted by the OUM method), etc., have been proved in practice as valuable and helpful tools for capturing, analyzing and documenting complex requirements of large systems. The quality of a good use case documentation (model) should not be judged largely or only by its size. It is possible as well that a quality and comprehensive use case model of a large system may finally evolve into hundreds of pages mainly because of the inherent complexity of the problem in hand, not because of the poor writing skills of its authors. [citation needed] ToolsText editors and/or word processors with template support are often used to write use cases. For large and complex system requirements, dedicated use case tools are helpful. Some of the well-known use case tools include:

Most UML tools support both the text writing and visual modeling of use cases. See also

References

Further reading

External links

|

Portal di Ensiklopedia Dunia