|

Triglav (mythology)

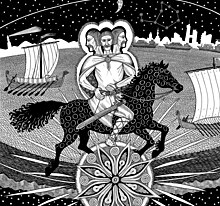

Triglav (lit. "Three-headed one"[1]) was the chief god of the Pomeranian and probably some of the Polabian Slavs, worshipped in Szczecin, Wolin and probably Brenna (now Brandenburg). His cult is attested to in several biographies of the bishop St. Otto of Bamberg in the years immediately preceding his suppression of it in 1127. Sources and historyIn Latin records, this theonym is noted as Triglau, Trigelaw, Trigelau, Triglou, Triglaff, Trigeloff.[2] Information about Triglav comes from three sources, the oldest being Life of Saint Otto, Bishop of Bamberg (Latin: Vita Prieflingensis) by an anonymous monk from Prüfening Abbey, written by 1146,[3] the second source is the 1151 Life of Saint Otto, Bishop of Bamberg by the monk Ebo, the third is Dialog on the Life of Saint Otto of Bamberg by the monk Herbord, written around 1158-1159.[a][3][5] These sources are biographies of St. Otto of Bamberg and describe his Christianization missions among the Baltic Slavs.[6] First missionOtto, after receiving permission from Pope Callistus II, goes to Pomerania to Christianize.[7] The bishop first arrives in Wolin (according to Anonymous on August 4,[8] according to Ebo on August 13,[9] 1124). Anonymous describes the local cult of "Julius Caesar's spear."[10] However, the Wolinians refuse to accept the new religion and force Otto to leave the city; he goes to Szczecin.[11] Herbord reports that Otto, after periodically hiding in the city, began Christianization on November 1, after receiving security guarantees from Boleslav III.[12] An anonymous monk briefly introduces the cult of Triglav and the destruction of his temple and statue: in the city there were supposed to be two richly decorated temples (Latin: continas) not far from each other that housed images of the gods, where the god Triglav was worshipped. One of the temples held a gilded and silver-plated saddle belonging to the god, as well as a well-built horse, which was used during prophecies: several spears were spread on the ground and the horse was led between them – if the horse, steered by the god, did not touch any spear with its foot, it meant good fortune and a good prediction for the upcoming battle or journey. Eventually, on Otto's orders, the temples were destroyed and the offerings distributed to the inhabitants. The bishop single-handedly destroyed the wooden statue of Triglav, taking only three silver-plated wooden heads from the statue, which he sent to the pope as proof that the residents had been baptized.[13] According to Herbord, there were four temples in Szczecin, including one richly decorated with paintings of people and animals, dedicated to the Triglav. Gold and silver "kraters," bull's horns decorated with precious stones that were drunk from or used as instruments, as well as swords, knives and furniture were dedicated to the god. The horse used during divination was black in color.[14] Ebo then goes on to describe how the priests of Wolin carted away the golden statue of Triglav to save it from destruction:[15]

Otto then demanded that the inhabitants abandon the cult of Triglav. Then Otto established two Wolin churches: one in the city, dedicated to St. Adalbert and St. Wenceslas, and the other outside the city, large and beautiful, St. Peter's Temple.[b] On March 28, 1125, Otto returns to his Archdiocese of Bamberg.[17] Second missionSoon afterwards, some Wolinians and Stettinians returned to their native faith,[17] as Ebo describes: In Wolin, the inhabitants, after burning idols during the first Christianization mission, began to create new statues decorated with gold and silver, and celebrated the feast of deities. For this, the Christian God was to punish them with fire from heaven.[18] He further states:

There was once an epidemic in the city, which the priests believed was sent by the gods as punishment for abandoning their faith, and that they should start offering sacrifices to the gods if they wanted to survive. Since then, pagan rituals and sacrifices began to be performed again in Szczecin, and Christian temples began to decline.[18] In April 1127, Otto returns to Pomerania to continue his Christianization mission.[19] In May and June, he carries out Christianization in Wolgast and Gützkow,[20] and on July 31 he returns to Szczecin.[21] Further, Ebo and Herbord report that pagan places of worship were destroyed, and that Christianization continued.[22] Other potential sourcesIt is possible that the cult Triglav was mentioned by the 13th-century writer Henry of Antwerp, who was well informed about the battles for Brenna in the mid-12th century, according to whom a three-headed deity was worshipped in the stronghold, but he does not give its name.[23][24][25][26] Some authors believe that Adam of Bremen's information about "Neptune"[c] worshipped in Wolin may refer to the Triglav.[25] Legacy Scholars have tried to find any references to the Triglav beyond the Polabia and Pomerania.[28] In this context, Mount Triglav in Slovenia[29][30][31] and the legend associated with it are often mentioned: "the first to appear from the water was the high mountain Triglav",[30] although Marko Snoj, for example, found the mountain's connection to a god unlikely.[32] Aleksander Gieysztor, following Josip Mal, cites the Triglav stone near Ptuj, whose name was mentioned in 1322.[d][29] There is a village Trzygłów in Poland, but it is within the range of the Szczecinian cult.[29] In northwestern Poland, folklorists have collected a number of local legends, according to which the statue of Triglav taken from Wolin was supposed to be hidden in the village of Gryfice, in Świętoujść on Wolin, in Tychowo under the erratic boulder Trygław, or in Jezioro Trzygłowskie ("Trzygłów's Lake").[33] In archaeologyThe Hill on which Szczecin's temple to Triglav was located was most likely identical to Castle Hill. At the top of the Hill there was supposed to be a circle surrounded by a ditch, which was originally a sacred circle (from the 8th century), later a temple of Triglav was built there, and later a Christian temple.[34] Brandenburg's Mound of Triglav is located about 0.5 kilometers from the fortress located on the island. A bronze horse, iron and decorative objects, including a lot of pottery, were discovered in the stronghold, indicating its importance and that an extensive religious cult may have been associated with it.[35] Interpretations The chthonic GodAccording to Aleksander Gieysztor, it should be considered that Triglav was a tribal god, separate from Perun, as indicated by Herbord's information that in Szczecin, in addition to temples, the place of worship included an oak tree and a spring,[e] which are attributes of the thunder god.[36] Gieysztor recognizes that Triglav was a god close to the chthonic Veles. According to him, this interpretation is supported by the fact that a black horse was sacrificed to Triglav, while Svetovit, interpreted by him as a Polabian hypostasis of Perun, received a white horse as sacrifice.[37] Andrzej Szyjewski also recognizes Triglav as a chthonic god.[26] He mentions the opinions of some researchers that the names Volos (Veles), Vologost, Volyn and Wolin are related to each other, and Herbord's information that "Pluto" – the Greek god of death – was worshipped in Wolin.[38] Trinity According to Jiří Dynda, Triglav may have been a three-headed god who combined the three gods responsible for Earth, Heaven, Underworld. In doing so, he cites the pass of "Neptune"[c] worshipped in Wolin and links this to Slovenian traditions regarding Mount Triglav, a three-leveled idol from Zbruch, a Wolin's sacred spear attached to a pole, and an oak tree with a spring which,[e] according to Dynda, corresponds to the Norse Yggdrasil and the wells beneath it, and the hiding of the god's statue in the tree all of which are said to be connected to the Axis mundi. Dynda proposes the following interpretations:[31]

Alleged influence of Christianity According to Henryk Lowmianski, the Triglav originated in Christianity – in the Middle Ages the Holy Trinity was depicted with three faces, which was later taken over by pagans in the form of a three-headed deity. However, this view cannot be accepted, since the depiction of the Holy Trinity with three faces is attested only from the 14th century, and the official condemnation by the Pope from 1628. The depiction of the Holy Trinity with three faces itself may be of pagan origin (Balkans).[28] According to Stanislaw Rosik, Christianity may have influenced the development of the Triglav cult in its declining phase. The significance may have been that for the Slavs the Christian God was a "German god," associated with a different ethnic group, but known from neighborly contacts and the later coexistence of the cult of Jesus and the Triglav (the so-called "doublefaith"). As pagans understood it, they linked the power of the deity to the military-political strength of the tribe in question, so the Pomeranians reckoned with a new deity, and the monolatrous (or henotheistic) worship of Triglav may have fostered his identification with Jesus on the basis of interpretatio Slavica. Such an alignment of religiosity fostered a later highlighting of the separateness of Jesus and Triglav, in accordance with Christian theology, and further demonization of Triglav after the final christianisation of Pomerania, which perhaps finds an outlet in the 15th-century Liber sancti Jacobi, where Triglav is referred to as "the enemy of mankind" and "the god or rather the devil."[39] In culture

References

Bibliography

Further reading

|

||||||||||||||||