|

Tintern Abbey

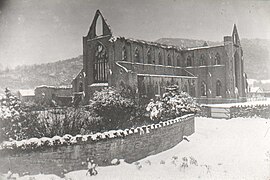

Tintern Abbey (Welsh: Abaty Tyndyrn ⓘ) was founded on 9 May 1131 by Walter de Clare, Lord of Chepstow. It is situated adjacent to the village of Tintern in Monmouthshire, on the Welsh bank of the River Wye, which at this location forms the border between Monmouthshire in Wales and Gloucestershire in England. It was the first Cistercian foundation in Wales, and only the second in Britain (after Waverley Abbey). The abbey fell into ruin after the Dissolution of the Monasteries in the 16th century. Its remains have been celebrated in poetry and painting from the 18th century onwards. In 1984, Cadw took over responsibility for managing the site. Tintern Abbey is visited by approximately 70,000 people every year.[1] HistoryEarliest historyThe Monmouthshire writer Fred Hando records the tradition of Tewdrig, King of Glywysing who retired to a hermitage above the river at Tintern. He then emerged to lead his son's army to victory against the Saxons at Pont-y-Saeson, a battle in which he was killed.[2] Cistercian foundationsThe Cistercian Order was founded in 1098 at the abbey of Cîteaux. A breakaway faction of the Benedictines, the Cistercians sought to re-establish observance of the Rule of Saint Benedict. Considered the strictest of the monastic orders, they laid down requirements for the construction of their abbeys, stipulating that "none of our houses is to be built in cities, in castles or villages; but in places remote from the conversation of men. Let there be no towers of stone for bells, nor of wood of an immoderate height, which are unsuited to the simplicity of the order".[3] The Cistercians also developed an approach to the Benedictine requirement for a dual commitment to pray and work that saw the evolving of a dual community, the monks and the lay brothers, illiterate workers who contributed to the life of the abbey and to the worship of God through manual labour.[4] The order proved exceptionally successful and by 1151, five hundred Cistercian houses had been founded in Europe.[5] The Carta Caritatis (Charter of Love) laid out their basic principles, of obedience, poverty, chastity, silence, prayer, and work. With this austere way of life, the Cistercians were one of the most successful orders in the 12th and 13th centuries. The lands of the Abbey were divided into agricultural units or granges, on which local people worked and provided services such as smithies to the Abbey. William Giffard, Bishop of Winchester introduced the first colony of Cistercian monks to England at Waverley, Surrey, in 1128. His first cousin, Walter de Clare, of the powerful family of Clare, established the second Cistercian house in Britain, and the first in Wales, at Tintern in 1131.[6] The Tintern monks came from a daughter house of Cîteaux, L'Aumône Abbey, in the diocese of Chartres in France.[7] In time, Tintern established two daughter houses, Kingswood in Gloucestershire (1139) and Tintern Parva, west of Wexford in southeast Ireland (1203). First and second abbeys: 1131–1536The present-day remains of Tintern are a mixture of building works covering a 400-year period between 1131 and 1536. Very little of the first buildings still survives today; a few sections of walling are incorporated into later buildings and the two recessed cupboards for books on the east of the cloisters are from this period. The church of that time was smaller than the present building, and slightly to the north.  The Abbey was mostly rebuilt during the 13th century, starting with the cloisters and domestic ranges, and finally the great church between 1269 and 1301. The first mass in the rebuilt presbytery was recorded to have taken place in 1288, and the building was consecrated in 1301, although building work continued for several decades.[8] Roger Bigod, 5th Earl of Norfolk, the then lord of Chepstow, was a generous benefactor; his monumental undertaking was the rebuilding of the church.[9] The earl's coat of arms was included in the glasswork of the Abbey's east window in recognition of his contribution. It is this great Decorated Gothic abbey church that can be seen today, representing the architectural developments of its period; it has a cruciform plan with an aisled nave, two chapels in each transept, and a square-ended aisled chancel. The abbey is built of Old Red Sandstone, with colours varying from purple to buff and grey. Its total length from east to west is 228 feet, while the transept is 150 feet in length.[10] King Edward II stayed at Tintern for two nights in 1326. When the Black Death swept the country in 1349, it became impossible to attract new recruits for the lay brotherhood; during this period, the granges were more likely to be tenanted out than worked by lay brothers, evidence of Tintern's labour shortage. In the early 15th century, Tintern was short of money, due in part to the effects of the Welsh uprising under Owain Glyndŵr against the English kings, when abbey properties were destroyed by the Welsh. The closest battle to Tintern Abbey was at Craig-y-dorth near Monmouth, between Trellech and Mitchel Troy. Dissolution and ruinIn the reign of Henry VIII, the Dissolution of the Monasteries ended monastic life in England, Wales and Ireland. On 3 September 1536, Abbot Wych surrendered Tintern Abbey and all its estates to the King's visitors and ended a way of life that had lasted 400 years. Valuables from the Abbey were sent to the royal Treasury and Abbot Wych was pensioned off. The building was granted to the then lord of Chepstow, Henry Somerset, 2nd Earl of Worcester. Lead from the roof was sold and the decay of the buildings began. Architecture and description

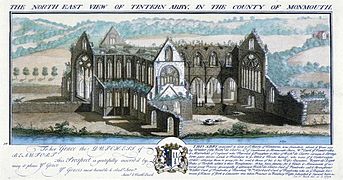

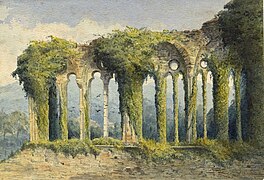

ChurchThe west front of the church, with its seven-light decorated window, was completed around 1300.[12] NaveThe nave is of six bays, and originally had arcades to both the northern and southern sides.[13] Monks' choir and presbyteryThe presbytery is of four bays, with a great east window, originally of eight lights. Almost all of the tracery is gone, with the exception of the central column and the mullion above.[14] CloisterThe cloister retains its original width, but its length was extended in the 13th century rebuilding, creating a near square.[15] Book room and sacristyThe book room parallels the sacristy and both were created at the very end of the construction period of the second abbey, around 1300.[16] Chapter houseThe chapter house was the place for daily gatherings of the monks, to discuss non-religious abbey business, make confession and listen to a reading from the Book of Rules.[17] Monks' dormitory and latrineThe monks' dormitory occupied almost the entirety of the upper storey of the east range.[18] The latrines were double-storeyed, with access both from the dormitory and from the day-room below.[18] RefectoryThe refectory dates from the early 13th century, and is a replacement for an earlier hall.[19] KitchenLittle of the kitchen, which served both the monks' refectory, and the lay brothers' dining hall, remains.[20] Lay brothers' dormitoryThe dormitory was sited above the lay brothers' refectory but has been completely destroyed.[20] InfirmaryThe infirmary, 107 ft long and 54 ft wide, housed both sick and elderly monks in cubicles in the aisles. The cubicles were originally open to the hall but were enclosed in the 15th century when each recess was provided with a fireplace.[21] Abbot's residenceThe abbot's lodgings date from two periods, its origins in the early 13th century, and with a major expansion in the late 14th century.[22] Industry Following the Abbey's dissolution, the adjacent area became industrialised with the setting-up of the first wireworks by the Company of Mineral and Battery Works in 1568 and the later expansion of factories and furnaces up the Angidy valley. Charcoal was made in the woods to feed these operations and, in addition, the hillside above was quarried for the making of lime at a kiln in constant operation for some two centuries.[23] The Abbey site was in consequence subject to a degree of pollution[24] and the ruins themselves were inhabited by the local workers. J.T.Barber, for example, remarked on "passing the works of an iron foundry and a train of miserable cottages engrafted on the offices of the Abbey" on his approach.[25] Not all visitors to the Abbey ruins were shocked by the intrusion of industry, however. Joseph Cottle and Robert Southey set out to view the ironworks at midnight on their 1795 tour,[26] while others painted or sketched them during the following years.[27] A 1799 print of the Abbey by Edward Dayes includes the boat landing near the ruins with the square-sailed local cargo vessel known as a trow drawn up there. On the bank is some of the encroaching housing, while in the background above are the cliffs of a lime quarry and smoke rising from the kiln. Though Philip James de Loutherbourg's 1805 painting of the ruins does not include the intrusive buildings commented on by others, it makes their inhabitants and animals a prominent feature. Even William Havell's panorama of the valley from the south pictures smoke rising in the distance (see Gallery), much as Wordsworth had noted five years before "wreathes of smoke sent up in silence from among the trees" in his description of the scene.[28] Tourism18th and 19th centuries By the mid-18th century it became fashionable to visit "wilder" parts of the country. The Wye Valley in particular was well known for its romantic and picturesque qualities and the ivy-clad Abbey was frequented by tourists. One of the earliest prints of the Abbey had been in the series of engravings of historical sites made in 1732 by Samuel and Nathaniel Buck.[29] Their sets of views, however, catered to antiquarian interests and often were a means to flatter the landowners involved and so gain orders for their publications.[30] Tourism as such developed in the following decades. The "Wye Tour" is claimed to have had its beginning after Dr John Egerton began taking friends on trips down the valley in a specially constructed boat from his rectory at Ross-on-Wye and continued doing so for a number of years.[31] Rev. Dr. Sneyd Davies' short verse epistle, "Describing a Voyage to Tintern Abbey, in Monmouthshire, from Whitminster in Gloucestershire", was published in 1745, the year Egerton took possession of his benefice. But that journey was made in the opposite direction, sailing from the Gloucestershire shore across the River Severn to Chepstow and then ascending the Wye.[32] Among subsequent visitors was Francis Grose, who included the Abbey in his Antiquities of England and Wales, begun in 1772 and supplemented with more illustrations from 1783. In his description he noted how the ruins were being tidied for the benefit of tourists: "The fragments of its once sculptured roof, and other remains of its fallen decorations, are piled up with more regularity than taste on each side of the grand aisle." There they remained for the next century and more, as is evident from the watercolours of J. M. W. Turner (1794), the prints of Francis Calvert (1815) and the photographs of Roger Fenton (1858). Grose further complained that the site was too well tended and lacked "that gloomy solemnity so essential to religious ruins".[33] Another visitor during the 1770s was the Rev. William Gilpin, who later published a record of his tour in Observations on the River Wye (1782),[34] devoting several pages to the Abbey as well as including his own sketches of both a near and a far view of the ruins. Though he too noted the same points as had Grose, and despite also the presence of the impoverished residents and their desolate dwellings, he found the Abbey nevertheless "a very inchanting piece of ruin". Gilpin's book helped increase the popularity of the already established Wye tour and gave travellers the aesthetic tools by which to interpret their experience. It also encouraged "its associated activities of amateur sketching and painting" and the writing of other travel journals of such tours. Initially Gilpin's book was associated with his theory of the Picturesque, but later some of this was modified by another editor so that, as Thomas Dudley Fosbroke’s Gilpin on the Wye (1818), the account of the tour could function as the standard guidebook for much of the new century.[35] Meanwhile, other more focussed works aimed at the tourist were available by now. They included Charles Heath’s Descriptive Accounts of Tintern Abbey, first published in 1793, which was sold at the Abbey itself and in nearby towns.[36] This grew into an evolving project that ran through eleven editions until 1828 and, as well as keeping abreast of the latest travel information, was also a collection of historical and literary materials descriptive of the building.[37] Later there appeared Taylor's Illustrated Guide to the Banks of the Wye, published from Chepstow in 1854 and often reprinted. The work of local bookseller Robert Taylor, it was aimed at arriving tourists and also available eventually at the Abbey.[38] Much the same information as in that work appeared later as the 8-page digest, An Hour at Tintern Abbey (1870, 1891), by John Taylor.[39]  Until the early 19th century, the local roads were rough and dangerous and the easiest access to the site was by boat. Samuel Taylor Coleridge, while trying to reach Tintern from Chepstow on a tour with friends in 1795, almost rode his horse over the edge of a quarry when they became lost in the dark.[40] It was not until 1829 that the new Wye Valley turnpike was completed, cutting through the abbey precinct.[41] In 1876 the Wye Valley Railway opened a station for Tintern. Although the line itself crossed the river before reaching the village, a branch was built from it to the wireworks, obstructing the view of the Abbey on the road approach from the north. 20th and 21st centuriesIn 1901, Tintern Abbey was bought by the Crown from the Duke of Beaufort for £15,000 and the site was acknowledged as a monument of national importance. Although there had been some repair work done in the ruins as a result of the 18th-century growth of tourism, it was not until now that archaeological investigation began and informed maintenance work was carried out on the Abbey. In 1914, responsibility for the ruins was passed to the Office of Works, who undertook major structural repairs and partial reconstructions (including removal of the ivy considered so romantic by the early tourists).[42] In 1984, Cadw took over responsibility for the site, which was Grade I listed from 29 September 2000.[43] The arch of the Abbey's watergate, which led from the Abbey to the River Wye, was Grade II listed from the same date.[44] In the visual artsEvidence of the growth of interest in the Abbey and the visitors attracted to it is provided by the number of painters who arrived to record aspects of the site. The painters Francis Towne (1777),[45] Thomas Gainsborough (1782),[46] Thomas Girtin (1793),[47] and J. M. W. Turner in the 1794–95 series now at the Tate[48] and the British Museum, depicted details of the Abbey's stonework.[49][50] So did Samuel Palmer (see Gallery) and Thomas Creswick in the 19th century,[51][52] as well as amateurs such as the father and daughter named Ellis who made a watercolour study of the refectory windows in the second half of the century (see Gallery). About that period too, the former painter turned photographer, Roger Fenton, applied this new art not only to detailing a later stage in the decay of the building,[53] but used the quality of light to emphasise it.[54]  Visiting artists also focused on the effects of light and atmospheric conditions. Charles Heath, in his 1806 guide to the abbey, had commented on the "inimitable" effect of the harvest moon shining through the main window.[55] Other moonlit depictions of the abbey include John Warwick Smith’s earlier 1779 scene of the ruins from across the river[56] and Peter van Lerberghe’s interior of 1812, with its tourist guides[57] carrying burning torches, which shows the abbey interior lit both by these and by moonlight. Once the railway had arrived in the vicinity, steam excursions were organised in the 1880s to Tintern station so as to view the harvest moon through the rose window.[58] Earlier in the century, the light effects made possible by transparencies (a forerunner of the modern photographic negative) had been deployed to underline such aspects of the picturesque. Among those described in the novel Mansfield Park (1814) as decorating its heroine’s sitting room, one was of Tintern Abbey.[59] The function of the transparencies was to reproduce light effects, such as “fire light, moon light, and other glowing illusions”, created by painting areas of colour on the back of a commercial engraving and adding varnish to make specific areas translucent when suspended in front of a light source.[60] Since the Abbey was one of the buildings recommended for viewing by moonlight, it is possible that this was the subject of the one in Fanny's room. In fact, a tinted print of the period such as those used for creating transparencies already existed in "Ibbetson's Picturesque Guide to Bath, Bristol &c", in which the full moon is featured as seen through an arch of the east wing.[61] Different light effects appear in the work of other painters, such as the sunsets by Samuel Palmer[62] and Benjamin Williams Leader, and the colour study by Turner in which the distant building appears as a "dark shape at the centre"[63] beneath slanting sunlight (see Gallery). Hybrid worksPrints of historical buildings along the Wye increased during the fourth quarter of the 18th century, with interior views and details of the Abbey's stonework among them.[64] Two later sets of these were distinguished by including a selection of unattributed verses. First came four tinted prints that mixed both distant and interior views of the building, published by Frederick Calvert in 1815.[65] The other was an anonymous set of views, with the same verses printed below. These were published by the London firm of Rock & Co. and later pasted on pages of an album in the King's Library. One set of verses hails the Abbey's survival, despite Henry VIII's dissolution, "Where thou in gothic grandeur reign’st alone". The phrase "gothic grandeur" derives from John Cunningham’s "An elegy on a pile of ruins”" (1761), an excerpt from which was published by Grose at the end of his description of Tintern Abbey. At that period the adjective was used as a synonym for "mediaeval"[66] and was so applied by Grose when describing the Abbey as being "of that stile of architecture called gothic".[67] Cunningham's poem was a melancholy contemplation of the ravages of time that spoke in general terms without naming a specific building. But the verses on the print are more positive in feeling; in celebrating the Abbey's historical persistence, they do not see ruin as necessarily a cause for regret. The scenes below which the verses appear are also quite different from each other. Calvert's view is across the river from the opposite bank of the Wye,[68] while the Rock print is close up to the ruins with the river in the background.[69]  Tintern is not specifically named in the verses mentioned above, although it is in two other sets and their poetic form overall is consistent: paired quatrains with pentameter lines rhymed alternately. One set begins "Yes, sacred Tintern, since thy earliest age," and King Henry is again represented as being foiled in his intention, but this time by no "earthly king". The Abbey's roof is now "of Heaven’s all glorious blue" and its pillars "foliaged… in vivid hue". Here Calvert's interior view looks past the ivy-grown pillars to the south window.[70] The Rock view that these lines accompany is of that same window, surrounded by ivy and viewed from the exterior.[71] Another set of verses begins "Thee! venerable Tintern, thee I hail", and celebrates the Abbey's setting. An appeal to Classical standards of beauty is made by calling the Wye by its Latin name of Vaga and referring to the serenading nightingale as Philomel. Naturally the river features in both prints, but where Calvert's is the south-east view from the high ground behind the Abbey, with the Wye flowing past it to the right,[72] the Rock view is from across the river, looking up to the high ground.[73] The remaining print by Calvert is another view of the interior in which a small figure in the foreground points down to a heap of masonry there,[74] while the Rock print corresponds to Calvert's view of the south window.[75] The accompanying stanzas deal with the transient nature of fame. Beginning “Proud man! Stop here, survey yon fallen stone”, their emotional tone is a melancholy at odds with the buoyant message of the other verses. It is uncertain whether all eight stanzas were originally from the same poem on the subject of the Abbey and what the relationship was between poet and artist. J. M. W. Turner had been accompanying his work with poetical extracts from 1798,[76] but it was not a widespread practice. However, the appearance of the title A Series of Sonnets Written Expressly to Accompany Some Recently-Published Views of Tintern Abbey, dating from 1816, the year after the appearance of Calvert's portfolio, suggests another contemporary marriage between literary and artistic responses to the ruins.[77] But while the main focus in Calvert's Four Coloured Engravings is the pictures, in a later hybrid work combining verse and illustration it is the text. Louisa Anne Meredith’s "Tintern Abbey in four sonnets" appeared in the 1835 volume of her Poems, prefaced by the reproduction of the author's own sketch of the ivy-covered north transept. This supplements in particular the description in the third sonnet: Th’ivy’s foliage twined Gallery

LiteraturePoetryA dedicatory letter at the start of Gilpin's Observations on the river Wye is addressed to the poet William Mason and mentions a similar tour made in 1771 by the poet Thomas Gray.[79] Neither of those dedicated a poem to the Abbey, but the place was soon to appear in topographical works in verse. Among the earliest was the 1784 six-canto Chepstow; or, A new guide to gentlemen and ladies whose curiosity leads them to visit Chepstow: Piercefield-walks, Tintern-abbey, and the beautiful romantic banks of the Wye, from Tintern to Chepstow by water by the Rev. Edward Davies (1719–89).[80] Furnished with many historical and topical discursions, the poem included a description of the method of iron-making in the passage devoted to Tintern, which was later to be included in two guide books, the most popular of which was successive editions of Charles Heath's.[81] Then in 1825 it was followed by yet another long poem, annotated and in four books, by Edward Collins: Tintern Abbey or the Beauties of Piercefield (Chepstow, 1825).[82] The Abbey also featured in poems arising from the Wye tour, such as the already mentioned account of his voyage by Rev. Sneyd Davies, in which the ruins are briefly reflected on at its end. It is that element of personal response that largely distinguishes such poems from verse documentaries of the sort written by Edward Davies and Edward Collins. For example, the gap between the ideal and the actual is what Thomas Warwick noted, looking upstream to the ruins of Tintern Abbey and downstream to those of Chepstow Castle, in a sonnet written at nearby Piercefield House.[83] Edward Jerningham's short lyric, "Tintern Abbey", written in 1796, commented on the lamentable lesson of the past, appealing to Gilpin's observations as his point of reference.[84] Fosbroke's later adaptation of that work is likewise recommended as a supplement to Arthur St John's more voluminous description in the account of his own tour along the river in 1819, The Weft of the Wye.[85]  Contemplation of the past reminded the Rev. Luke Booker of his personal mortality in an "Original sonnet composed on leaving Tintern Abbey and proceeding with a party of friends down the River Wye to Chepstow"; inspired by his journey, he hopes to sail as peacefully at death to the "eternal Ocean".[86] And Edmund Gardner (1752?–1798), with his own death imminent, similarly concluded in his "Sonnet Written in Tintern Abbey", that "Man’s but a temple of a shorter date".[87] William Wordsworth’s different reflections followed a tour on foot that he made along the river in 1798, although he does not actually mention the ruins in his "Lines written a few miles above Tintern Abbey". Instead, he recalls an earlier visit five years before and comments on the beneficial internalisation of that memory.[88] Later Robert Bloomfield made his own tour of the area with friends, recording the experience in a journal and in his long poem, "The Banks of the Wye" (1811). However, since the timetable of the boat-trip downstream was constrained by the necessity of the tide, the Abbey was only given brief attention as one of many items on the way.[89][90] Aspects of the building's past were treated at much greater length in two more poems. George Richards' ode, "Tintern Abbey; or the Wandering Minstrel", was probably written near the end of the 18th century. It opens with a description of the site as it used to be, seen from outside; then a minstrel arrives, celebrating the holy building in his song as a place of loving nurture, of grace and healing.[91] The other work, "The Legend of Tintern Abbey", is claimed as having been "written on the Banks of the Wye" by Edwin Paxton Hood, who quotes it in his historical work, Old England.[92] An 11-stanza poem in rolling anapaestic metre, it relates how Walter de Clare had murdered his wife and built the Abbey in penitence. Closing on an evocation of the ruins by moonlight, the work was later reprinted in successive editions of "Taylor's Illustrated Guide" over the following decades. Louisa Anne Meredith used the occasion of her visit to reimagine the past in a series of linked sonnets that allowed her to pass backwards from the present-day remains, beautified by the mantling vegetation, to bygone scenes, "Calling them back to life from darkness and decay".[93] For Henrietta F. Vallé, "Seeing a lily of the valley blooming among the ruins of Tintern" was sufficient to mediate the pious sentiments of a former devotee there. As she noted, "it must ever awaken mental reflection to see beauty blossoming among decay".[94] But the religious strife of the following decades forbade such a sympathetic response and made a new battleground of the ruins. "Tintern Abbey: a Poem" (1854) was, according to its author, Frederick Bolingbroke Ribbans (1800–1883), "occasioned by a smart retort given to certain Romish priests who expressed the hope of soon recovering their ecclesiastical tenure of it". He prefers to see the building in its present decay than return to the time of its flourishing, "when thou wast with falsehood fill’d".[95] Martin Tupper too, in his sonnet "Tintern Abbey" (1858), exhorts his readers to "Look on these ruins in a spirit of praise", insofar as they represent "Emancipation for the Soul" from superstition.[96] Only a few years earlier, in his 1840 sonnet on the Abbey, Richard Monckton Milnes had deplored the religious philistinism which had "wreckt this noble argosy of faith". He concluded, as had Louisa Anne Meredith's sonnets and the verses accompanying Calvert's prints, that the ruin's natural beautification signified divine intervention, "Masking with good that ill which cannot be undone".[97] In the wake of the Protestant backlash since then, Hardwicke Drummond Rawnsley was constrained to allow, in the three sonnets he devoted to the Abbey, that after "Men cramped the truth" the building's subsequent ruin had followed as a judgment. However, its renewed, melodic blossoming now stands as a reproach to Tupper's brand of pietism too: "Man, fretful with the Bible on his knee,/ Has need of such sweet musicker as thee!"[98] In the 20th century two American poets returned to Wordsworth's evocation of the landscape as the launching pad for their personal visions. John Gould Fletcher’s "Elegy on Tintern Abbey" answered the Romantic poet's optimism with a denunciation of subsequent industrialisation and its ultimate outcome in the social and material destructiveness of World War I.[99] Following a visit some thirty years later, Allen Ginsberg took lysergic acid near there on 29 July 1967 and afterwards wrote his poem "Wales Visitation" as a result.[100][101] By way of "the silent thought of Wordsworth in eld Stillness" he beholds "clouds passing through skeleton arches of Tintern Abbey" and from that focus goes on to experience oneness with valleyed Wales.[102] FictionIn 1816, the abbey was made the backdrop to Sophia Ziegenhirt's three-volume novel of Gothic horror, The Orphan of Tintern Abbey, which begins with a description of the Abbey as seen on a sailing tour down the Wye from Ross to Chepstow.[103] Her work was dismissed by The Monthly Review as "of the most ordinary class, in which the construction of the sentences and that of the story are equally confused".[104] During the 20th century the genre switched to supernatural fiction, starting with "The Ghost of Tintern Abbey" (1901) by Mrs (Harriet Margaret Anne) Arthur Traherne, which is the means of discovering a murder.[105] It was followed by "The Troubled Spirit of Tintern Abbey", a story privately printed in 1910 under the initials 'E. B.' which was later included in Lord Halifax’s Ghost Book (1936). There an Anglican cleric and his wife are on a cycling tour in the Wye valley and are contacted by a ghost from Purgatory who persuades them to have masses said for his soul.[106] Later came Henry Gardner's novella, "The Ghost of Tintern Abbey", in 1984.[107] The more recent novel, Gordon Master's The Secrets of Tintern Abbey (2008), covers the building's mediaeval history as the author dramatises the turbulent 400 years of the Cistercian community up to the monastery's dissolution.[108] References

Sources

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Tintern Abbey, Wales.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Portal di Ensiklopedia Dunia