|

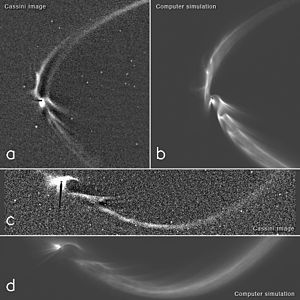

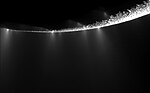

Tiger stripes (Enceladus) The tiger stripes of Enceladus consist of four sub-parallel, linear depressions in the south polar region of the Saturnian moon.[1][2] First observed on May 20, 2005, by the Cassini spacecraft's Imaging Science Sub-system (ISS) camera (though seen obliquely during an early flyby), the features are most notable in lower resolution images by their brightness contrast from the surrounding terrain.[3] Higher resolution observations were obtained by Cassini's various instruments during a close flyby of Enceladus on July 14, 2005. These observations revealed the tiger stripes to be low ridges with a central fracture.[2] Observations from the Composite Infrared Spectrometer (CIRS) instrument showed the tiger stripes to have elevated surface temperatures, indicative of present-day cryovolcanism on Enceladus centered on the tiger stripes.[4] NamesThe name tiger stripes is an unofficial term given to these four features based on their distinctive albedo. Enceladean sulci (subparallel furrows and ridges), like Samarkand Sulci and Harran Sulci, have been named after cities or countries referred to in The Arabian Nights. Accordingly, in November 2006, the tiger stripes were assigned the official names Alexandria Sulcus, Cairo Sulcus, Baghdad Sulcus and Damascus Sulcus (Camphor Sulcus is a smaller feature that branches off Alexandria Sulcus).[5] Baghdad and Damascus sulci are the most active, while Alexandria Sulcus is the least active. Appearance and geology Images from the ISS camera onboard Cassini revealed the 4 tiger stripes to be a series of sub-parallel, linear depressions flanked on each side by low ridges.[2] On average, each tiger stripe depression is 130 kilometers long, 2 kilometers wide, and 500 meters deep. The flanking ridges are, on average, 100 meters tall and 2–4 kilometers wide. Given their appearance and their geologic setting within a heavily tectonically deformed region, the tiger stripes are likely to be tectonic fractures.[2] However, their correlation with internal heat and a large, water vapor plume suggests that tiger stripes might be the result of fissures in Enceladus' lithosphere. The stripes are spaced approximately 35 kilometers apart. The ends of each tiger stripe differ in appearance between the anti-Saturnian and sub-Saturnian hemisphere. On the anti-Saturnian hemisphere, the stripes terminate in hook-shaped bends, while the sub-Saturnian tips bifurcate dendritically.[2] Virtually no impact craters have been found on or near the tiger stripes, suggesting a very young surface age. Surface age estimates based on crater counting yielded an age of 4–100 million years assuming a lunar-like cratering flux and 0.5-1 million years assuming a constant cratering flux.[2] CompositionAnother aspect that distinguishes the tiger stripes from the rest of the surface of Enceladus are their unusual composition. Nearly the entire surface of Enceladus is covered in a blanket of fine-grained water ice. The ridges that surround the tiger stripes are often covered in coarse-grained, crystalline water ice.[2][6] This material appears dark in the Cassini camera's IR3 filter (central wavelength 930 nanometers), giving the tiger stripes a dark appearance in clear-filter images and a blue-green appearance in false-color, near-ultraviolet, green, near-infrared images. The Visual and Infrared Mapping Spectrometer (VIMS) instrument also detected trapped carbon dioxide ice and simple organics within the tiger stripes.[6] Simple organic material has not been detected anywhere else on the surface of Enceladus. The detection of crystalline water ice along the tiger stripes also provides an age constraint. Crystalline water ice gradually loses its crystal structure after being cooled and subjected to the Saturnian magnetospheric environment. Such a transformation into finer-grained, amorphous water ice is thought to take a few decades to a thousand years.[7] Cryovolcanism  Observations by Cassini during the July 14, 2005 flyby revealed a cryovolcanically active region on Enceladus centered on the tiger stripe region. The CIRS instrument revealed the entire tiger stripe region (south of 70° South latitude) to be warmer than expected if the region were heated solely from sunlight.[4] Higher resolution observations revealed that the hottest material near Enceladus' south pole is located within the tiger stripe fractures. Color temperatures between 113 and 157 kelvins have been obtained from the CIRS data, significantly warmer than the expected 68 kelvins for this region of Enceladus. Data from the ISS, Ion and Neutral Mass Spectrometer (INMS), Cosmic Dust Analyser (CDA) and CIRS instruments show that a plume of water vapor and ice, methane, carbon dioxide, and nitrogen emanates from a series of jets located within the tiger stripes.[9][10] The amount of material within the plume suggests that the plume is generated from a near-surface body of liquid water.[2] Over 100 geysers have been identified on Enceladus.[8] Alternatively, Kieffer et al. (2006) suggest that Enceladus' geysers originate from clathrate hydrates, where carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrogen are released when exposed to the vacuum of space by the fractures.[11] Enceladus - Cryovolcanism Relation to E-Ring of SaturnPlumes from the moon Enceladus, which seems similar in chemical makeup to comets,[12] have been shown to be the source of the material in the E Ring.[13] The E Ring is the widest and outermost ring of Saturn (except for the tenuous Phoebe ring). It is an extremely wide but diffuse disk of microscopic icy or dusty material. The E ring is distributed between the orbits of Mimas and Titan.[14] Numerous mathematical models show that this ring is unstable, with a lifespan between 10,000 and 1,000,000 years, therefore, particles composing it must be constantly replenished.[15] Enceladus is orbiting inside this ring, in a place where it is narrowest but present in its highest density, raising suspicion since the 1980s that Enceladus is the main source of particles for the E ring.[16][17][18][19] This hypothesis was confirmed by Cassini's first two close flybys in 2005.[20][21]

Eruptions on Enceladus may seem to be "discrete" jets, but may be "curtain" eruptions instead (video animation) References

External links

|

Portal di Ensiklopedia Dunia