|

Thomas Ingles

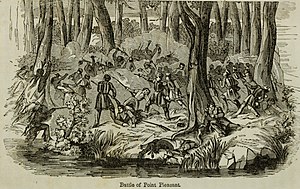

Thomas Ingles (1751–1809, sometimes spelled Thomas Inglis or Thomas English) was a Virginia pioneer, frontiersman and soldier. He was the son of William Ingles and Mary Draper Ingles. He, his mother and his younger brother were captured by Shawnee Indians and although his mother escaped, Thomas remained with the Shawnee until age 17, when his father paid a ransom and brought him back to Virginia. He later served in the Virginia militia, reaching the rank of colonel by 1780. Early life and captivity Ingles was born in 1751 on the Ingles family farm at Draper's Meadow, a pioneer settlement on the banks of Stroubles Creek near modern-day Blacksburg, Virginia.[1]: 116–118 His younger brother George was born there in 1753.[2] On 30 July (or 8 July, according to John P. Hale[1] and Letitia Preston Floyd[3]: 79–109 [Note 1]), 1755, during the French and Indian War, a band of Shawnee warriors (then allies of the French) raided Draper's Meadow and killed six settlers, including Mary's mother and her infant niece.[6][2] They took five captives, including Mary and her sons George and Thomas, her sister-in-law Bettie Robertson Draper, and her neighbor Henry Lenard (or Leonard).[7][8][9] Thomas's father William was nearly killed but fled into the forest.[10] Mary and her sons were taken to Lower Shawneetown at the confluence of the Ohio River and the Scioto River, on what is now the Ohio-Kentucky border. Mary was separated from her two sons, and Thomas was taken to Detroit. George was taken to an unknown location and probably died soon afterward.[1] In October, Mary and another woman escaped and walked for 42 days to return to Draper's Meadow.[10] Ransom and return to VirginiaBetween 1756 and 1768, Thomas' father William Ingles made several trips to Ohio to negotiate for the release of his son Thomas.[11] William met a man named Baker who had been held captive by the Shawnee at Lower Shawneetown, and had known Thomas and his adoptive father.[1]: 115 [12]: 86–88 William hired Baker to find Thomas (now living at Pickaway Plains on the upper Scioto River) and bring him back to Ingles Ferry. Baker traveled to the village, located Thomas, and was able to pay a ransom of $150 to bring him back, but during the journey, Thomas ran away and returned to his Shawnee family.[13] In 1768, William Ingles and Baker traveled together to Lower Shawneetown and persuaded Thomas, now 17, to return with them to Virginia.[1]: 116 After thirteen years among the Shawnee, Thomas had become fully acculturated and spoke only Shawnee, so William sent him for several years of "rehabilitation" and education under Dr. Thomas Walker at Castle Hill, Virginia.[14]: 176 [12][13] Thomas' son Thomas Jr. later wrote that, while at Castle Hill, Thomas Sr. studied violin together with Thomas Jefferson.[15] Military career On 7 May, 1774, Thomas Ingles was commissioned as a lieutenant in the Fincastle County Militia[16]: 1 and served under Colonel William Christian in Lord Dunmore's War against the Shawnee.[17]: 281 [18]: 51–52 On 10 October 1774, Ingles and his father William participated in the Battle of Point Pleasant,[19][20]: 69 [21]: 22 although Thomas' son Thomas Jr. later wrote that his father's regiment did not reach the battlefield until after the battle had ended.[15][22]: 722–26 Following the battle, Thomas was stationed in the fort at Point Pleasant (Fort Blair), and took the opportunity to return to his former Shawnee home on the Scioto to visit his adoptive family.[20]: 69 According to his nephew, he "stayed some time with them."[13] He served as a company captain in the Montgomery County, Virginia militia during the American Revolutionary War,[23]: 35 and, according to his son, received a commission as Colonel of Militia from Thomas Jefferson.[15] Kidnapping of wife and children, 1782He married Eleanore Grills in 1775 and in 1778 he settled in Wright's Valley, near what is now Bluefield, West Virginia.[24]: 69 In 1780, the family relocated to Burke's Garden, Virginia. In 1782, while Thomas was absent, his wife and three children were kidnapped by Indians, led by Black Wolf.[25]: 14–15 [12]: 86–88 [26]: 96 Thomas and a group of volunteers pursued the Indians who had taken them, and after five days they were able to launch an attack.[24]: 70–71 In the ensuing altercation, the Indians killed the two older children, and Eleanore was tomahawked.[27] Thomas rescued her and their youngest daughter, as well as two of his Black slaves the Indians had also captured. Eleanor survived after several pieces of her fractured skull were removed by a surgeon.[26]: 90–92 [15][12]: 446 She bore five more children after this, including four sons and a daughter, according to her son Thomas Jr.[15] Later lifeFollowing his father William's death in 1782, Thomas Ingles took over the operation of Ingles Ferry.[28]: 75 [29]: 51 William's will of 6 September 1782, dictates: "Son Thomas a tract of land 1000 [acres] on the Blue Stone, known by the name of Absolem's Valley, and a slave."[30] The 1782 Montgomery County, Virginia Personal Property Tax List shows that he was assessed for taxes on two slaves, 12 horses and 15 cattle.[31] On 3 August 1786, Thomas served as a commissioner for the State of Franklin,[32]: 346 together with William Cocke, Alexander Outlaw, and Samuel Wear, for the Treaty of Coyatee, in which the State of Franklin forced Corntassel, Hanging Maw, John Watts, and the other Overhill Cherokee leaders to cede to the State of Franklin the remaining land between the boundary set by the Treaty of Dumplin Creek and the Little Tennessee River.[33]: 98 After 1786 he moved to Tennessee with his wife and children and lived on the Watauga River, at Mossy Creek.[1]: 129 His son Thomas Jr. was born in Grainger County, Tennessee in 1791.[15] He had a home in Nashville, Tennessee in 1798, where he was visited by James Weir, who described him as "a gentleman of distinguished civility."[34]: 57 In February 1800, he relocated to Port Gibson, Mississippi.[15] He died at Natchez, Mississippi in 1809.[1]: 142 See alsoExternal links

Notes

References

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Portal di Ensiklopedia Dunia