|

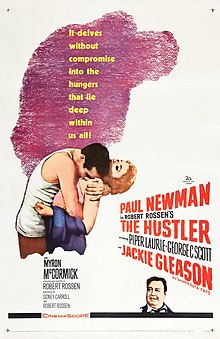

The Hustler

The Hustler is a 1961 sports drama film, directed by Robert Rossen. It tells the story of small-time pool hustler "Fast Eddie" Felson, who challenges legendary pool player "Minnesota Fats". The film, which was based on the 1959 book of the same name by Walter Tevis, stars Paul Newman as Fast Eddie, Jackie Gleason as Minnesota Fats, Piper Laurie as Sarah, George C. Scott as Bert, and Myron McCormick as Charlie. The Hustler was a major critical and popular success, gaining a reputation as a modern classic. Its exploration of winning, losing, and character garnered a number of major awards; it is also credited with helping to spark a resurgence in the popularity of pool.[3] In 1997, the Library of Congress selected The Hustler for preservation in the United States National Film Registry as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".[4][5] The Academy Film Archive preserved The Hustler in 2003.[6] A 1986 sequel, The Color of Money, starred Newman reprising his role as Felson, for which he won his only Academy Award. Plot"Fast Eddie" Felson is accompanied by his partner, Charlie, at a pool room in a small town. Pretending to be salesmen on their way to a convention, Eddie and Charlie convince onlookers that Eddie is a drunk blowhard, and induce them to bet on Eddie to lose a trick shot. He wins and takes their money. Eddie and Charlie arrive in Ames, Iowa, where Eddie challenges the legendary player Minnesota Fats to play straight pool for $200 a game. After initially falling behind, Eddie surges back to being $1,000 ahead and suggests raising the bet to $1,000 a game. Eddie gets ahead $11,000 and Charlie tries to convince him to quit, but Eddie insists the game will end only when Fats says it is over. Fats agrees to continue after a spectator, the professional gambler Bert Gordon, labels Eddie a "loser". After 25 hours and an entire bottle of bourbon, Eddie is ahead over $18,000, but loses it all along with all but $200 of his original stake. Fats declares the game over. At their hotel later, Eddie leaves a sleeping Charlie without saying goodbye. Eddie stashes his belongings in a locker at a bus terminal, where he meets Sarah Packard, an alcoholic. They begin a relationship and he moves in with her. Charlie finds Eddie at Sarah's apartment and tries to persuade him to go back out on the road. Eddie refuses and Charlie realizes he plans to challenge Fats again. Eddie learns that Charlie had money he could have used to rebound and beat Fats. Eddie dismisses Charlie as a scared old man and tells him to "lay down and die by yourself". Eddie joins a poker game where Bert is playing. Afterward, Bert tells Eddie that he has talent as a pool player but no character. He figures that Eddie will need at least $3,000 to challenge Fats again. Bert calls him a "born loser" but nevertheless offers to stake him in return for 75% of his winnings; Eddie refuses. Eddie goes back to hustling to get the money he needs to play Fats. After hustling a local player at a pool room near the waterfront, Eddie is attacked after winning and his thumbs are broken. After Sarah helps Eddie convalesce, and when he’s ready to play, he agrees to Bert's terms, deciding that a "25% slice of something big is better than a 100% slice of nothing". Bert, Eddie and Sarah travel to the Kentucky Derby, where Bert arranges a match for Eddie against a wealthy local socialite named Findley. The game turns out to be three-cushion billiards, not pool. When Eddie loses badly, Bert refuses to keep staking him. Sarah pleads with Eddie to leave with her, saying that the world he is living in and its inhabitants are "perverted, twisted, and crippled"; he refuses. Seeing Eddie's anger, Bert agrees to let the match continue at $1,000 a game. Eddie comes back to win $12,000. He collects his $3,000 share and decides to walk back to the hotel where he discovers that Sarah has committed suicide, because of Bert's sadism. Eddie returns to challenge Fats again, putting up his entire $3,000 stake on a single game. He wins game after game, beating Fats so badly that Fats is forced to quit. Bert demands half of Eddie's winnings and threatens to have him beaten unless he pays. Eddie says he will come back to kill Bert if he survives, shaming Bert into giving up his claim by invoking Sarah's memory. Instead, Bert orders Eddie never to walk into a big-time pool hall again. Eddie and Fats compliment each other as players, and Eddie walks out. Cast

Pool champion Willie Mosconi has a cameo appearance as Willie, who holds the stakes for Eddie and Fats's games. Mosconi's hands also appear in many of the closeup shots. Production The Tevis novel had been optioned several times, including by Frank Sinatra, but attempts to adapt it for the screen were unsuccessful. Director Rossen's daughter Carol Rossen speculates that previous adaptations focused too much on the pool aspects of the story and not enough on the human interaction. Rossen, who had hustled pool himself as a youth and who had made an abortive attempt to write a pool-themed play called Corner Pocket, optioned the book and teamed with Sidney Carroll to produce the script.[7] According to Bobby Darin's agent, Martin Baum, Paul Newman's agent turned down the part of Fast Eddie.[8] Newman was originally unavailable to play Fast Eddie regardless, being committed to star opposite Elizabeth Taylor in the film Two for the Seesaw.[9] Rossen offered Darin the part after seeing him on The Mike Wallace Interview.[10] When Taylor was forced to drop out of Seesaw because of shooting overruns on Cleopatra, Newman was freed up to take the role, which he accepted after reading just half of the script.[9] No one associated with the production officially notified Darin or his representatives that he had been replaced; they found out from a member of the public at a charity horse race.[11] Rossen filmed The Hustler over six weeks, entirely in New York City. Much of the action was filmed at two now-defunct pool halls, McGirr's and Ames Billiard Academy.[12] Other shooting locations included a townhouse on East 82nd Street, which served as the Louisville home of Murray Hamilton's character Findley, and the Manhattan Greyhound bus terminal. The film crew built a dining area that was so realistic that confused passengers sat there and waited to place their orders.[13] Willie Mosconi served as technical advisor on the film[12] and shot a number of the trick shots in place of the actors. All of Gleason's shots were his own; they were filmed in wide-angle to emphasize having the actor and the shot in the same frames.[14] Rossen, in pursuit of the style he termed "neo-neo-realistic",[15] hired actual street thugs, enrolled them in the Screen Actors Guild and used them as extras.[16] Scenes that were included in the shooting script but did not make it into the final film include a scene at Ames pool hall establishing that Eddie is on his way to town (originally slated to be the first scene of the film) and a longer scene of Preacher talking to Bert at Johnny's Bar which establishes Preacher is a junkie.[17] Early shooting put more focus on the pool playing, but during filming Rossen made the decision to place more emphasis on the love story between Newman and Laurie's characters.[18] Despite the change in emphasis, Rossen still used the various pool games to show the strengthening of Eddie's character and the evolution of his relationship to Bert and Sarah, through the positioning of the characters in the frame. For example, when Eddie is playing Findley, Eddie is positioned below Bert in a two shot but above Findley while still below Bert in a three shot. When Sarah enters the room, she is below Eddie in two-shot while in a three-shot Eddie is still below Bert. When Eddie is kneeling over Sarah's body, Bert again appears above him but Eddie attacks Bert, ending up on top of him. Eddie finally appears above Bert in two-shot when Eddie returns to beat Fats.[19] ThemesThe Hustler is, fundamentally, a story of what it means to be a human being, couched within the context of winning and losing.[14][20] Describing the film, Robert Rossen said: "My protagonist, Fast Eddie, wants to become a great pool player, but the film is really about the obstacles he encounters in attempting to fulfill himself as a human being. He attains self-awareness only after a terrible personal tragedy which he has caused — and then he wins his pool game."[20] Roger Ebert concurs with this assessment, citing The Hustler as "one of the few American movies in which the hero wins by surrendering, by accepting reality instead of his dreams".[14] The film was also somewhat autobiographical for Rossen, relating to his dealings with the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). A screenwriter during the 1930s and '40s, he had been involved with the Communist Party in the 1930s and refused to name names at his first HUAC appearance. Ultimately he changed his mind and identified friends and colleagues as party members. Similarly, Felson sells his soul and betrays the one person who really knows and loves him in a Faustian pact to gain character.[21] Rossen also takes aim at capitalism, often showing money as a malign and corrupting influence. Eddie, Bert and Findley are all shown to be perverted by their pursuit of money. Of the pool hall inhabitants, only Minnesota Fats, who never handles money himself, focusing only on the game he is playing, is uncorrupted and undamaged by the end. He is beaten, but knows when to quit. Rossen often points out and exposes class divisions; for example, when Minnesota Fats asks Preacher, a junkie willing to run errands, to get him some "White Tavern whiskey, a glass and some ice", Eddie counters by ordering cheap bourbon, without any of the niceties: "J.T.S. Brown, no ice, no glass." Film and theatre historian Ethan Mordden has identified The Hustler as one of a handful of films from the early 1960s that re-defined the relationship of films to their audiences. This new relationship, he writes, is "one of challenge rather than flattery, of doubt rather than certainty".[22] No film of the 1950s, Mordden asserts, "took such a brutal, clear look at the ego-affirmation of the one-on-one contest, at the inhumanity of the winner or the castrated vulnerability of the loser".[23] Although some have suggested the resemblance of this film to classic film noir, Mordden rejects the comparison based on Rossen's ultra-realistic style, also noting that the film lacks noir's "Treacherous Woman or its relish in discovering crime among the bourgeoisie, hungry bank clerks and lusty wives".[23] Mordden does note that while Fast Eddie "has a slight fifties ring",[24] the character "makes a decisive break with the extraordinarily feeling tough guys of the 'rebel' era ... [b]ut he does end up seeking out his emotions"[24] and telling Bert that he is a loser because he's dead inside.[24] ReceptionThe Hustler had its world premiere in Washington, D.C., on September 25, 1961. Prior to the premiere, Richard Burton hosted a midnight screening of the film for the casts of the season's Broadway shows, which generated a great deal of positive word of mouth.[25] Initially reluctant to publicize the film, 20th Century-Fox responded by stepping up its promotional activities.[26] Box office was healthy, with estimated eventual U.S. - Canada rentals of $3,000,000, according to Variety magazine.[27] On review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes, the film has an approval rating of 94% based on 50 reviews, with an average rating of 8.6/10. The website's critical consensus reads: "Paul Newman and Jackie Gleason give iconic performances in this dark, morally complex tale of redemption."[28] Metacritic assigned the film a weighted average score of 90 out of 100, based on 18 critics, indicating "universal acclaim".[29] The film was well received by critics, although with the occasional reservation. Variety praised the performances of the entire main cast but felt that the "sordid aspects" of the story prevented the film from achieving the "goal of being pure entertainment".[30] Variety also felt the film was far too long. Stanley Kauffmann, writing for The New Republic, concurred in part with this assessment. Kauffmann strongly praised the principal cast, calling Newman "first-rate" and writing that Scott's was "his most credible performance to date". Laurie, he writes, gives her part "movingly anguished touches" (although he also mildly criticizes her for over-reliance on Method acting). While he found that the script "strains hard to give an air of menace and criminality to the pool hall" and also declares it "full of pseudo-meaning", Kauffmann lauds Rossen's "sure, economical" direction, especially in regard to Gleason who, he says, does not so much act as "[pose] for a number of pictures which are well arranged by Rossen. It is the best use of a manikin by a director since Kazan photographed Burl Ives as Big Daddy."[31] A. H. Weiler of The New York Times, despite finding that the film "strays a bit" and that the romance between Newman and Laurie's characters "seems a mite far-fetched", nonetheless found that The Hustler "speaks powerfully in a universal language that spellbinds and reveals bitter truths".[32] Accolades American Film Institute Lists:

SequelPaul Newman reprised his role as "Fast Eddie" Felson in the 1986 film The Color of Money, for which he won his one and only Academy Award for Best Actor in a Leading Role. A number of observers and critics have suggested that this Oscar was in belated recognition for his performance in The Hustler,[14][47] as well as some of his other Oscar-nominated performances in films like Cool Hand Luke and The Verdict. Legacy In the decades since its release, The Hustler has cemented its reputation as a classic. Roger Ebert, echoing earlier praise for the performances, direction, and cinematography and adding laurels for editor Dede Allen, cites the film as "one of those films where scenes have such psychic weight that they grow in our memories".[14] He further cites Eddie as one of "only a handful of movie characters so real that the audience refers to them as touchstones".[14] TV Guide calls the film a "dark stunner",[48] offering "a grim world whose only bright spot is the top of the pool table, yet [with] characters [who] maintain a shabby nobility and grace".[48] The four leads are again lavishly praised for their performances and the film is summed up as "not to be missed".[48] Carroll and Rossen's screenplay was selected by the Writers Guild of America in 2006 as the 96th best motion picture screenplay of all time.[49] In June 2008, AFI released its "Ten top Ten"—the best ten films in ten "classic" American film genres—after polling over 1,500 people from the creative community. The Hustler was acknowledged as the sixth best film in the sports genre.[50][51] The Hustler is credited with sparking a resurgence in the popularity of pool in the United States, which had been on the decline for decades.[3] The film also brought recognition to Willie Mosconi, who, despite having won multiple world championships, was virtually unknown to the general public.[52] Perhaps the greatest beneficiary of the film's popularity was a real-life pool hustler named Rudolf Wanderone. Mosconi claimed in an interview at the time of the film's release that the character of Minnesota Fats was based on Wanderone, who at the time was known as "New York Fatty". Wanderone immediately adopted the Minnesota Fats nickname and parlayed his association with the film into book and television deals and other ventures. Author Walter Tevis denied for the rest of his life that Wanderone had played any role in the creation of the character.[53] Other players would claim, with greater or lesser degrees of credibility, to have served as models for Fast Eddie, including Ronnie Allen, Ed Taylor, Eddie Parker, and Eddie Pelkey.[54] See alsoWikiquote has quotations related to The Hustler (film).

ReferencesNotes

Bibliography

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to The Hustler (film). Wikiquote has quotations related to The Hustler.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||