|

Tanmono

A tanmono (反物) is a bolt of traditional Japanese narrow-loomed cloth. It is used to make traditional Japanese clothes, textile room dividers, sails, and other traditional cloth items. Tanmono (物, mono is a placeholder name[clarification needed]) are woven in units of tan, a traditional unit of measurement for cloth roughly analogous to the bolt, about 35–40 centimetres (14–16 in) by about 13 yards (12 m).[1][2] One kimono takes one tan (ittan)[3] of cloth to make.[4] Tanmono are woven in the narrow widths most ergonomic for a single weaver[2] (at a handloom without a flying shuttle). FibersTanmono may be woven of a variety of fibers, including silk, wool, hemp, linen and cotton. Polyester is also popular, as it is easy to wash at home.[5][6] In the Jomon period (8000–300 BC) people made twined textiles from a variety of bast fibers from wild plants. Wild fibers (nuno) include the inner bark of wild trees or shrubs (juhi), and grass fibers (sohi).[7] Between the 2nd and 3rd centuries BC, immigrants from the mainland began using the domesticated long-stapled ramie plant. Silk was also known at this time,[7] but used only by the upper classes. Paper was developed in the 3rd and 4th century AD, and woven textiles including paper fibers likely began to be woven around the 5th and 6th century AD, though there is little early record.[8] In the 7th and 8th century AD, Tang-dynasty immigrants brought new production techniques for textiles, and Japanese silk weaving improved.[7] Silk was used for high-class fabrics,[9] with silk noil from broken, lumpy or discarded silk cocoons used to weave lower-class materials such as tsumugi, a type of soft, uneven slub-woven silk with little of its typical shine. In the 1400s, cotton was introduced from Korea. Cotton did not become widely available throughout Japan until the mid-1700s; commoners continued to rely on wild and cultivated bast fibers.[7] Working-class fabrics were mostly made of hemp or ramie (asa).[a] Cotton was more expensive, especially outside the western regions of Japan, where it was grown. Second-hand cotton cloth was, however, sold to rural farmers outside these areas, and was preferred over hemp fabric for its softness and heat-retaining properties. Weaving was largely a cottage industry until cotton cloth was first machine-made in Japan in the 1870s.[9] Tanmono are now often machine-woven. Kamiko ('paper-child') is a soft, flexible paper with cotton or silk attached to the reverse side. It is highly thermally-insulating. Kimono of kamiko were worn by the poor of the Edo period; more expensive kamiko kimono were elaborately decorated. Kamiko was also used to make other garments.[10] Meisen, a bright, crisp, durable fabric machine-made from silk noil, was first made in the late 19th century and became extremely popular in the 1920s and 1930s. It is a glossier mechanized version of tsumugi. Wool, especially merino, was introduced in the same periods and widely worn. Rayon (jinken) started to be widely used in the 1920s; early rayon was made using the cupro process, which is still used in one factory in Japan as of 2020[update].[11] Though improvements to the rayon production process significantly improved the durability of late-20th-century rayon, early Japanese rayon fabrics are known for their poorer durability, being more prone to age-related degradation, due to fibres being weakened when brought into contact with water.[12][13] Most rayon is now produced using the viscose process, which uses toxic carbon disulfide.[14] Carbon disulfide emissions are declining for rayon produced in Japan, but in major producing countries, they are uncontrolled (as of 2004[update])[15] and unknown,[16][17] as is their health toll.[18][19] List of fibers

WeavesFour basic weaves are commonly used for tanmono.[20] Hira-ori, a plain tabby weave, is simple, hardwearing, and widely used. Aya-ori or shamon-ori is twill weave, and produces soft, draping cloth. Shusu-ori is satin weave; it is thick and lustrous with a heavy drape,[20][21] but the long floats mean that the fabric tends to snag. Black shusu silk was previously commonly used as the reverse side for chūya obi. Mojiri-ori is a category of gauze weaves used for sha, ro and ra gauzes. They use twisted warps.[20] Mon-ori (pattern weaving) includes patterning by varying the weave and patterning by weaving with variably-dyed threads. Woven patterns include aya (patterned twill), donsu (satin damask), rinzu (figured silk) and mon-chirimen (patterned chirimen).[20]

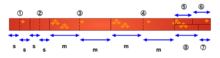

Weaving, dimensions and use Tanmono are woven narrow instead of being cut to a narrow width, with both vertical edges being selvages. Widths around 40 cm (16 in) are standard, as these were ergonomically the easiest widths to weave on a hand loom[2] without a flying shuttle. Hand-woven and handspun tanmono are still made in Japan, but they are much more expensive, and the industry is in decline. For instance, though in previous decades, up to 20,000 craftspeople were involved in the production of Ōshima tsumugi (a variety of slub-woven silk produced in Amami Ōshima) in 2017, just 500 craftspeople were left.[24] Some varieties of tanmono, previously produced out of necessity by the lower and working classes, are now produced by hobbyists and craftspeople for their rustic appeal. For instance, saki-ori was historically woven from old kimono cut into strips roughly 1 centimetre (0.39 in), with one obi requiring roughly three old kimono to make.[25] Traditionally an article of thrift, sakiori obi are now expensive informal pieces of clothing, prized for their limited production and craftsmanship. Although modern tanmono are mostly machine-woven, the narrow width of most tanmono remains a standard of production. Modern Western fabrics, and traditional fabrics made on automatic looms, are typically much wider; they are less commonly used for kimono production. However, unusually-wide tanmono, designed for use as altar cloth or for maru obi, are sometimes found. Wider tanmono, and more commonly longer tanmono, are also occasionally sold for kimono production; some of these are woven larger to accommodate larger figures, with longer tanmono typically being used to produce a matching kimono, juban and haori set for men.[3][12] A second set of kimono sleeves could also be produced, so that a kimono could feature either regular short sleeves or long sleeves.[26] Alternatively, a tanmono of standard length might contain nothing but supplementary sleeves, sold with tanmono for matching kimono.[26] Shorter lengths are also woven, for garments that need less cloth; for instance, a hajaku is a shorter length woven to make a haori (a length woven for a kimono is called a kijaku).[27][better source needed] In approximately the Meiji period (1868–1912), the bolt length for kimono was standardized. Excess length was adjusted with a tuck-seam across the back, and, for women, by adjusting the depth of the ohasori (waist tuck).[26] By the 20th century, the standard width of a woman's tanmono was roughly 35 centimetres (14 in), with men's tanmono being woven wider, to roughly 40–45 centimetres (16–18 in); historically, bolts were woven to order, so length would vary by both the size of the wearer and the type of garment. However, tanmono for both men and women were woven to roughly 40–45 cm (16–18 in) as standard until late in the 1600s. As a result, the kosode, the direct predecessor of the kimono, had fuller and wider proportions to the modern-day kimono.[28][additional citation(s) needed] If the fabric is a single solid colour, or the pattern was komon (a small all-over reversible pattern), the bolt can be cut anywhere. Otherwise, the patterns would be spaced so that it was in the right place relative to where the cloth would be cut (for instance, so that a kimono's hem patterns were located at the hem on all body panels). The garment's seam width is adjusted so that the finished garment fits the person, instead of cutting the cloth narrower.[3][28] Excess is folded under and hemmed, not cut off.[29][6] Sewn tucks are taken in children's clothing, and let out as the child grows.[30]: 15 A garment made from a tanmono can be disassembled for cleaning (arai-hari, typically for more expensive or formal kimono), re-dyeing, and repairs;[3] it may also be disassembled to rotate the pieces for more even wear,[12] or to be re-sized. When the cloth is worn out, it may be used as fabric for smaller items or to create boroboro (patchwork) futons or garments. The fact that the pattern pieces of a kimono consist of rectangles, and not complex shapes, make reuse in other items or garments easier.[1] Patchwork garments were very popular in the 1500s, and are traditionally worn by Buddhist monks as vestments.[28] The cloth used for patchwork clothing must all be of similar weight, elasticity, and stiffness.

Decoration Tanmono are decorated with a variety of techniques, either in the weaving process, through embroidery, dyework, a combination of techniques or others, such as appliqué. The decorative technique used on or while constructing the fabric generally designates its end use. For kimono, designs dyed into the fibres and yarns used for weaving before the fabric's construction, including ikat dyeing, are considered informal, with designs dyed into the fabric after weaving and embroidered designs used for more formal kimono. For obi, woven patterns are conversely considered the most formal, with designs dyed onto the fabric and embroidered designs paired with less formal kimono. If a tanmono is to be used for a formal kimono, such as a hōmongi, tsukesage, irotomesode or kurotomesode, it is temporarily stitched together (kari-eba) so the pattern can be drawn across the seams. For less formal kimono, the pattern is drawn and applied to the fabric before it is cut and constructed, as the design is not intended to match up over the seams, or the kimono will have a solid colour.[3] Tsukesage kimono use a non-reversible pattern laid out with respect to where the cuts will fall, but no seam-crossing patterns. Komon, a reversible all-over pattern (such as geometric or sprigged patterns), is used for everyday komon kimono, but also for other garments, such as kataginu and hakama.[31] Designs for children's clothing were not distinguishably gender-specific until the end of the 1700s.[32] Traditionally, tanmono would be dyed and even woven to order; though kimono are still mostly made to order, tanmono are now commonly bought ready-made to be sewn later. Modern tanmono for less formal kimono are often dyed with inkjet printers,[6] though formal kimono are more likely to be dyed by hand. Kasuri Most ikat-woven, indigo-dyed cotton fabrics – known as kasuri – were historically hand-woven by the working classes, who of necessity spun and wove their own clothing until cheaper ready-to-wear clothing became widely available. Indigo, being the cheapest and easiest-to-grow dyestuff available to many, used due to its specific dye qualities; a weak indigo dyebath could be used several times over to build up a hard-wearing colour, whereas other dyestuffs would be unusable after one round of dyeing. Working-class families commonly produced books of hand-woven fabric samples known as shima-cho – literally, "stripe book", as many fabrics were woven with stripes – which would then be used as a dowry for young women and as a reference for future weaving. With the introduced of ready-to-wear clothing, the necessity of weaving one's own clothes died out, leading to many of these books becoming heirlooms instead of working reference guides.[33] Sakiori obi are one-sided, and also often feature ikat-dyed designs of stripes, checks and arrows, commonly using indigo dyestuff.[34] RinzuRinzu is a figured silk fabric, typically with figurative or geometric motifs. As the pattern is made by varying the texture of the weave, it can be additionally decorated with dyed or embroidered patters. Resist dyeing Techniques such as resist-dyeing are commonly used. These techniques range from intricate shibori tie-dye to rice paste resist-dyeing (yūzen etc.). Though other forms of resist, such as wax-resist dye techniques, are also seen in kimono, forms of shibori and yūzen are the most commonly seen.[citation needed] For repeated patterns covering a large area of base cloth, resist dyeing is typically applied using a stencil, a technique known as katazome. The stencils used for katazome were traditionally made of washi paper layers laminated together with an unripened persimmon tannin dye known as kakishibu.[35] Other types of rice-paste resist were applied by hand, a technique known as tsutsugaki, commonly seen on both high-quality expensive kimono and rural-produced kimono, noren curtains and other house goods. Though hand-applied resist dyeing on high-end kimono is used so that different colours of dye can be hand-applied within the open spaces left, for rural clothes and fabrics, tsutsugaki was often applied to plain cloth before it was repeatedly dipped in an indigo dye vat, leading to the iconic appearance of white-and-indigo rural clothes, with rice paste sometimes applied over previously open areas to create areas of lighter blue on a darker indigo background. Tie-dye and clamping techniques (shibori) Another form of textile art used on kimono is shibori, a form of tie dye that ranges from the most basic fold-and-clamp techniques to intricate kanoko shibori dots taking years to fully complete. Patterns are created by a number of different techniques binding the fabric, either with shapes of wood clamped on top of the fabric before dyeing, thread wrapped around minute pinches of fabric, or sections of fabric drawn together with thread and then capped-off using resistant materials such as plastic or (traditionally) the sheaths of the Phyllostachys bambusoides plant (known as either kashirodake or madake in Japan), amongst other techniques.[36] Fabric prepared for shibori is mostly dyed by hand, with the undyed pattern revealed when the bindings are removed from the fabric. Shibori techniques cover a range of formalities, with all-shibori yukata (informal), all-shibori furisode (formal) and all-shibori obiage all being particularly common. Shibori can be further enhanced with the time-consuming use of hand-painted dyes, a technique known as tsujigahana (lit. 'flowers at the crossroads'). This was a common technique in the Muromachi period, and was revived in the 20th century by Japanese dye artist Itchiku Kubota. Due to the time-consuming nature of producing shibori fabrics and the small pool of artists possessing knowledge of the technique, only some varieties are still produced, and brand-new shibori kimono are exceedingly expensive to buy. List of decoration types

See also

Garments and other cloth items

Regional varieties of tanmono

Notes

References

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Tanmono. |

Portal di Ensiklopedia Dunia