|

Susan Curtiss

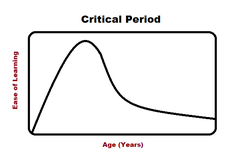

Susan Curtiss is an American linguist. She is Professor Emerita at the University of California, Los Angeles.[1] Curtiss's main fields of research are psycholinguistics and neurolinguistics.[2] Her 1976 UCLA PhD dissertation[3] centered on the study of the grammatical development of Genie, a famous feral child.[4] Her subsequent work has been on grammatical development in children with SLI;[5] maturational constraints on first-language development ("critical period" effects);[6] hemispheric specialization for language and language acquisition;[7][8] and the cognitive modularity of grammar.[9][10] BiographySusan Curtiss received her undergraduate degree from the University of California, Berkeley. She attended the University of California, Los Angeles where her doctoral advisor was Victoria Fromkin.[1] There, she studied Genie, the feral child. Curtiss wrote her doctoral thesis on Genie. Curtiss's dissertation is now regarded as the most significant research that addressed Genie’s acquisition of language. After receiving her PhD, she continued to study critical periods, modularity, and grammatical development at UCLA. She is married and has two daughters.[11] Work with GenieIn November 1970, the child welfare authorities of Los Angeles discovered a young girl who had been subject to extreme isolation and abuse. At the time of her discovery, the girl, who was given the pseudonym “Genie,” was approximately 13 years and 7 months old, and it was determined that her isolation began at around 20 months of age.[12] Many people were involved in Genie’s case including social workers, psychologists, and linguists. In May 1971, Susan Curtiss, alongside a team of researchers, began researching Genie. When Genie was admitted to the hospital, at the age of 13 years and 7 months, doctors concluded that she had not acquired a first language. The research team set out to determine whether Genie was capable of comprehending or producing language. They found she could understand far more than she was able to produce, and from there, the team tried to both teach Genie facets of the English language as well as test her understanding of how to employ those features.[13] Curtiss, specifically, set out to teach Genie the difference between singular and plural count nouns. Curtiss developed a game to help Genie understand the plural construction rule—Curtiss would say a noun phrase such as “four horses,” and Genie would find the index card that had the number 4, the index card that had a picture of horses, and the index card that had the letter “s” to construct that phrase. Using this game, Genie was able to learn regular English pluralization in 3 weeks.[13] Over the course of study, Genie’s language developed in several ways. The researchers noted, however, that there were significant differences between Genie’s language development and that of a normal child—surprisingly, considering her limited exposure to language at the time she was placed into custody, Genie’s vocabulary rapidly grew very large. For example, after 7 months in the hospital, Genie could produce about 200 words whereas a child at the equivalent linguistic stage can produce about 50 words. To contrast, her syntax was quite limited. Genie acquired few syntactic rules, and she produced few sentences longer than 3 words. Curtiss and her research team found that despite Genie’s limited acquisition of syntax, she had relatively advanced cognitive abilities. Curtiss observed isolated incidents in which she believed Genie showed evidence of using recursion, a complex feature of human language.[14] Genie’s linguistic development was seen as an opportunity to research critical periods. Prior to the research done on Genie, it was hypothesized that the critical period to acquire a first language would end when the brain lateralized, meaning the tendency for certain functions of the brain to be localized to one hemisphere as opposed to the other.[15] Language is typically localized to the left hemisphere. It is widely held that process of lateralization of the brain ends during puberty, typically around the age of 13.[16] Curtiss and her team determined that Genie was most likely right-handed, but on dichotic listening tests they discovered that Genie, unlike most right-handed people, was right-hemisphere dominant for language; she had normal results for environmental sounds, proving that her brain was not simply reversed in dominance for language. Curtiss and her team hypothesized that the critical period may not end with the lateralization of the brain. If that were the case, Genie would have acquired no language as the left hemisphere of her brain could not be responsible for the language she had acquired thus far.[16] Curtiss's work with Genie has been frequently cited as evidence for the critical period for syntax. In 1976, Curtiss completed her doctoral thesis and received her PhD from UCLA. Curtiss's thesis is the most significant research that has been published on Genie. In 1977, Academic Press published her thesis as a book titled Genie: A Psycholinguistic Study of A Modern-Day “Wild Child."[11] As part of her work with Genie, Curtiss was featured in the 1994 Nova documentary Secret of the Wild Child[17] and the 2003 "Wild Child" episode of the television series Body Shock.[18] She was a script consultant for the movie Mockingbird Don't Sing (2001), and was the only person directly involved in the case to be involved in the film's making.[19] ControversyGenie’s case has been a source of controversy. During the years in which Genie was studied, Jean Butler (who later began using her married name, Ruch), Genie’s former teacher and foster parent, argued against the research. Ruch claimed that David Rigler, principal investigator of the Genie case, was putting the research ahead of Genie’s best interests and that Curtiss was a hindrance around the home that Ruch and Genie lived in. She further accused Rigler and Curtiss of disregarding data from the two months Ruch’s own home as it did not align with the goals of their research. The Riglers, who became Genie's foster parents immediately afterwards, and Curtiss said that Ruch's writing about Genie's social and linguistic development were highly inconsistent with their observations from immediately after her removal from Ruch's home.[11] In the years following Curtiss's work with Genie, some scholars have cast doubt on her research. It has been suggested that Curtiss's findings were inconsistent, stating that there was not enough evidence to support the claim that Genie was not acquiring significant syntax, and rather that Curtiss presented examples to the contrary.[20] Others have suggested that studying Genie and administering tests was unethical. Genie's mother argued that Genie was over-tested and that the research team violated confidentiality rules. As a result, she filed a lawsuit in 1979 against those who researched Genie.[11] Some scholars argued that the team put the research ahead of Genie’s best interests. Jay Shurley and David Elkind, who were involved in the early phases of Genie's case study, left the research team over these concerns.[11][21] Additionally, people believe that members of the research team took on too many roles in an attempt to study, befriend, and parent Genie.[20] Each of the researchers hold that they never put their work ahead of Genie’s wellbeing, and there are several scholars who support them, stating that they treated Genie as a human rather than a test subject. Other Major AccomplishmentsCritical PeriodsSusan Curtiss's work with Genie lent itself greatly to her research on critical periods. As the case study of Genie demonstrated, reaching puberty without having had significant exposure to language does not mean that an individual will be unable to communicate for the remainder of their life. Rather, it means that while the individual can learn vocabulary but will be extremely unlikely to learn the syntax of the language.[13] In 1980, Curtiss began research on a woman who was given the pseudonym “Chelsea.” Chelsea, 32, had been born deaf, but in childhood was not diagnosed as such. This misdiagnosis led to Chelsea never receiving any language input from American Sign Language (ASL) nor any auditory input. Additionally, no system of home-sign ever arose in her home. Local social services requested an examination of Chelsea when she was 32, leading to the discovery that she was deaf. At that time, she was fitted with her first pair of hearing aids, and began working with Susan Curtiss.[22]  Curtiss observed that Chelsea was able to learn new vocabulary quickly, similarly to Genie. Chelsea showed strength in regard to semantics and categorizing words according to their meanings. However, she was unable to develop her syntactic abilities in any significant way. Curtiss noted that Chelsea was unable to consistently produce utterances that were well-formed. Chelsea struggled to generate sentences that followed the Subject-Verb-Object (SVO) word order of English. Curtiss notes that Chelsea was able to grasp many of the non-verbal characteristics of conversation, such as turn-taking, conversational fillers, and facial expressions.[22] Curtiss compares Genie and Chelsea, offering both cases as supporting evidence for a critical period for syntax. Neither of these two individuals had significant exposure to language prior to reaching puberty, and despite attempts to teach them English, neither of them was able to grasp syntax. Curtiss notes that Genie was able to grasp certain facets of the English language, such as phrasal categories, whereas Chelsea was only able to enlarge her lexicon and understand discourse.[22] ModularityCurtiss has also done research on the modularity of grammar, exploring syntax and semantics are separate faculties of human language. In pursuit of this, Curtiss has conducted research on children who show evidence of dissociating different faculties of language from one another. This research has also served as evidence for the modularity of grammar. In her 1981 article titled Dissociations Between Language and Cognition: Cases and Implications, Curtiss explores the language systems of three children: Genie, Antony, and Marta.[23] The data Curtiss collected from Genie’s case allowed her to conclude that not only were Genie’s syntactic and semantic faculties modular, but also that Genie’s cognitive abilities were not sufficient for further syntactic development. Antony, a mentally retarded 6 year old, was able to produce syntactically well-formed sentences, but they were semantically incorrect. His speech contained the very features that Genie’s speech lacked, further demonstrating the modularity of syntax and semantics as well as showing that there isn’t an innate preference towards one or the other. Marta, later referred to by her real first name, Laura, had a testable IQ between 41 and 48. From an early age she showed strength regarding the syntactic and morphological features of language, but her speech was frequently neither semantically correct nor fully intelligible.[24][23] These cases serve as evidence supporting Curtiss's commitment to the modularity of syntactic and semantic faculties.  In addition to her research on children who dissociate various language faculties, Curtiss researched the language of elderly adults with Alzheimer’s disease and compared the results to that of elderly adults with unimpaired mental status. The 1987 study was titled Syntactic Preservation in Alzheimer's Disease.[25] Both the group of Alzheimer’s patients and the normal control group were recorded speaking in regular conversation; 50 utterances were transcribed from each participant to determine the number of errors made. The errors were then classified as either syntactic errors or semantic errors. She found that the patients with Alzheimer’s made significantly more semantic errors than syntactic errors. The control group made few errors, with a greater tendency towards syntactic errors.[25] Similar results were produced from a written trial, wherein the Alzheimer’s patients made more semantic errors than syntactic errors. These data supported Curtiss's belief that syntax was preserved to a greater degree than semantics in Alzheimer's patients.[26] Curtiss also determined that the number of errors made by each Alzheimer's patient correlated with the severity of the disease.[25] Curtiss has also helped develop several key language tests for use by clinicians and researchers to diagnose language development. The CYCLE (Curtiss Yamada Comprehensive Language Evaluation) Test is widely used to diagnose language development and language impairments in children and adults.[27] Another test, the CYCLE-N (Curtiss Yamada Comprehensive Language Evaluation—Neurological), was designed specifically for adults and for mapping grammar in the brain.[28] These tests are administered to children and adults with various conditions including autism, Specific Language Impairment (SLI), and dementia to determine which language faculty has been affected so that clinicians can determine the best course of treatment.[29] Language Impaired (LI) Children Susan Curtiss has performed significant research in the field of language development in children with various language impairments compared to normal children. In 1987, Curtiss provided a report to the US Congress.[30] This report offers data pertaining to the phonology, morphology, syntax, semantics, and pragmatics of both language impaired (LI) and normal English-speaking children as well as provides different subcategories of language impairment. Curtiss notes that LI children understand phonological rules, but that their language system allows for errors in phonology that a normal child’s language system would not. Additionally, there is no data to show that LI children do not grasp morphological rules of their language. Indeed, normal children and LI children learn the same morphemes in the same order, but LI children begin to use those morphemes earlier though they take longer to master the appropriate usage. Curtiss notes that LI children often make syntactically unacceptable utterances, although they have the same syntactic categories. She suggests that these children may be creating sentences outside the rules of grammar. The semantics of LI children were the same as normal children of the same stage of language, meaning they created utterances of the same mean length (MLU). The data regarding the pragmatics of LI children were inconsistent. Although each of these areas is in need of further research, it is clear that pragmatics remains the most unclear.[30] Curtiss suggested that not all LI children show the same performance abilities and deficits. Therefore, she classified LI children into the following four subcategories: 1. Receptively Impaired, meaning that the receptive language was in greater deficit 2. Expressively Impaired, meaning that the expressive language was in greater deficit 3. Severely Impaired, meaning that both receptive and expressive language were more than a year below the cognitive age 4. Mildly Impaired, meaning that both receptive and expressive language were more than a year below the cognitive age when averaged together[31] Researchers observed that receptively impaired children demonstrated conversational initiative that was not reflected by any of the other subcategories of LI children or normal children. Several differences were noted in the syntactic abilities among the four subcategories of LI children at the age of 4. Expressively impaired children used the narrowest range of syntactic structures when compared with the other subcategories of LI children, and both expressively impaired and severely impaired children had difficulty mastering syntactically complex structures. Interestingly, these differences were no longer apparent in the children by age 5. Curtiss concluded from these data that the subcategories of LI children highlight “psycholinguistic and neuropsychological impairments” in the children rather than linguistic deficits.[30] Specific Language Impairment (SLI)In 1989, Curtiss published a study titled Familial Aggregation in Specific Language Impairment, in which she examined the concurrence of language impairments within family units.[32] Specific Language Impairment (SLI) is a language impairment in which a child’s language develops atypically, but their difficulties cannot be attributed to factors such as autism or slow development. Curtiss's study aimed to determine if there was a probable genetic factor involved in SLI. The researchers collected data from 76 SLI children, as well as 54 control children who were matched for age, ethnicity, and IQ. Data was also collected from the family of each child. Researchers found that the parents of SLI children were significantly more likely to report having had language impairments of their own than the parents of normal children. The siblings of impaired children were also more likely to have language impairments than the siblings of normal children. Furthermore, for families that had two language impaired parents, siblings were 52.6% more likely to have language impairments. In families where only one parent had a language impairment, the rate of sibling impairment was 31.6%. Families in which neither parent was language impaired showed a 25% rate of siblings being language impaired. Indeed, this study showed that SLI children are far more likely to have parents or siblings that are language impaired than normal children. The researchers observed that “most families reported either several [SLI] cases in the same family or no [SLI] cases at all.”[32] Selected publicationsEach of the following publications can be found on Curtiss's website:[33]

See alsoReferences

|

||||||||||||||||

Portal di Ensiklopedia Dunia