|

Silas Soule

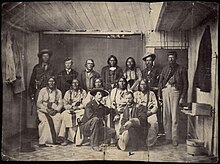

Silas Stillman Soule (/soʊl/ SOHL; July 26, 1838 – April 23, 1865) was an American abolitionist, a teenage 'conductor' on the Underground Railroad, military officer, and an early example of what would later be called a whistleblower. As a Kansas Jayhawker, he supported and was a proponent of John Brown's movement in the time of strife leading up to the American Civil War. During the war, Soule joined the Colorado volunteers, and rose to the rank of captain in the Union Army. Soule was in command of 1st Colorado Cavalry, Company D that was present at Sand Creek and the massacre of Native Americans that occurred there on November 29, 1864. He testified at a U.S. military hearing that convened in February 1865 to investigate the event. Soule was murdered two months later in what some believed was retaliation. Early lifeSilas Soule was born into a family of abolitionists in Bath, Maine, descended from Mayflower passenger George Soule[1] He was raised in Maine and Massachusetts. Soule was a "...friendly, intelligent, and good-natured young man, full of practical jokes, [and] tall tales...[2] In 1854, his family became part of the newly formed New England Emigrant Aid Company, an organization whose goal was to help settle the Kansas Territory and bring it into the Union as a free state. His father and brother arrived in the vicinity of modern day Lawrence in November 1854, and became one of the town's founding families. The teenage Silas, his mother, and two sisters came the following summer.[3] Shortly after the family's arrival at Coal Creek located a few miles south of Lawrence,[a] Silas's father, Amasa, established his household as a stop on the Underground Railroad. At the age of 17, Silas escorted escaped slaves from Missouri north to freedom.[b] Strife in Kansas During the late 1850s, pro-slavery forces from Missouri and abolitionist forces from Kansas were engaged in open warfare. The conflict was over whether Kansas would be admitted to the Union as a slave or free state. This period was often called "Bleeding Kansas". In July 1859, twenty pro-slavery men had crossed into Kansas to look for escaped slaves. They located and ambushed an Underground Railroad party led by Dr. John Doy, a physician in Lawrence, who was escorting 13 former slaves[c] to Iowa. The men from Missouri arrested Dr. Doy and sold the former slaves. Doy, meanwhile, was tried and convicted of abducting slaves and sentenced to five years in a Missouri penitentiary. Because he was awaiting transfer to the prison at the jailhouse in St. Joseph, Soule and a group of men from Lawrence decided they would free him. Soule went into the jail and convinced the jailkeeper that he had a letter from Doy's wife. The note in fact read: "Tonight, at twelve o'clock." Later that night they overpowered the jailer and helped Doy escape back to Kansas.[5] Thereafter known as "The Immortal Ten", when they reached Lawrence they had their photo taken (above left).[d]  Later that year, after John Brown was captured following the raid on Harper's Ferry, Soule once again found himself planning a jailbreak. Brown had been tried, convicted, and sentenced to death by hanging, when, in November 1859, Soule visited him and offered to help him escape. Brown told Soule, however, that he had already decided to become a martyr for the abolitionist cause and would willingly allow himself to be hanged, hoping his death would help bring on a war between North and South. This frustrated Soule's planned rescue attempt. Nonetheless, pastor and Secret Six member, Thomas Wentworth Higginson, an associate of Soule's, put together a rescue attempt of two men who had also been incarcerated along with Brown, Albert Hazlett and Aaron Dwight Stevens. As part of this plan, Soule posed as a drunken Irishman, got himself arrested for brawling, and was put into the Charles Town jail for the night. He managed to convince the jailer into letting him out of his cell for a short while during which he contacted Brown and the two men. Brown, Hazlett, and Stevens all refused to be sprung from the jail, choosing instead to become martyrs for the cause. After his release from the Charles Town jail, Soule traveled to Boston, where he often met with various abolitionists and befriended the poet Walt Whitman.[1] Life in Colorado and the Civil WarIn May 1860, Soule—along with his brother William, and his cousin, Sam Glass—went to the gold fields in Colorado where he dug for gold and worked in a blacksmith shop.[6] In 1861, after the start of the Civil War, Soule enlisted in Company K; 1st Colorado Infantry,[e] and took part in the New Mexico campaign of 1862, including the key Battle of Glorieta Pass. In November 1864, he was assigned the command of Company D, 1st Colorado Cavalry Regiment. The Sand Creek MassacreOn November 29, 1864, at Sand Creek, in what was then the southeastern corner of territorial Colorado, Colonel John Chivington ordered the Third Colorado Cavalry to attack Southern Cheyenne Chief Black Kettle's encampment of Southern Cheyenne. Before the attack, Soule told other officers “any man who would take part in [such] murders, knowing the circumstances as we did, was a low lived cowardly son of a bitch.” [7] Several lieutenants also objected to Chivington's plans. Lt. Joseph Cramer and Soule went directly to Major Scott Anthony, Chivington's superior.[1] As the attack began, Soule reminded his troops that the supposed "enemy" was a peace chief's band, and some responded that they "would not fire a shot today".[1] His company did not follow the orders given to them to enter the creek bed leading to the settlement but moved up and down the banks and observed the slaughter. There was heavy crossfire,[f] and they did not participate in the killings. After the attack, in Chivington's telegram reporting his "victory" he condemned Soule for "saying that he thanked God he killed no Indians, and like expressions, proving himself more in sympathy with the Indians that the whites."[1]  The U.S. Congress created a congressional committee to investigate the Sand Creek Massacre due to a nationwide outrage of the incident. Soule's and others' verbal and written testimonies about the Sand Creek Massacre led to Chivington's resignation; Colorado's Second Territorial Governor, John Evans’, dismissal; and the U.S. Congress refusing the U.S. Army's repeated requests for a general war against the Plains Indians.[8] Personal life and family

Soule was "...a great favorite with the men of his own military company..." and could express a "...devilish sense of humor..."being able to "...slither under the thickest skin of pro-slavery or Union supporter alike, with his sharp tongue, cynical nature and charming wit ... [being] wise beyond his years and able to separate the wheat from the chaff on matters of politics..."[2] On April 1, 1865, Soule married Thersa A. "Hersa" Coberly; the marriage lasted just twenty-two days before he was murdered.[7] Following his death, his widow remarried. She and her second husband, Alfred Lea, became the parents of the adventurer, author, and geopolitical strategist Homer Lea.[1]  DeathOn April 23, 1865, two months after testifying before a U.S. military commission investigating the Sand Creek Massacre, Soule was on duty as provost marshal of the Colorado Territory in Denver, when he went to investigate guns being fired. At around 10:30 p.m., with his pistol out, Soule went around a corner in what is now downtown Denver, and faced Charles Squier. Soule fired the first shot and wounded Squier's left arm, but Squier fired a bullet that entered Soule's right cheek, mortally wounding him. Soule was dead before help could arrive. Squier dropped his pistol and ran before he could be arrested by the authorities. Soule's assassination occurred two weeks after the end of the Civil War.[1] One of Soule's assassins fled the scene, but Squier was eventually caught and brought back to Denver for a court-martial. However, the officer who captured Squier was found dead in a Denver hotel with what was presumed to be a staged drug overdose, and Squier escaped to New York, where his father lived. Once there he held various jobs, and tried to rejoin the Army, but was rejected. Squier then fled to Central America to avoid the law. His legs were crushed in a railroad accident, and he later died from gangrene in 1869. Despite his crime, he was buried in New York with honors.[2][9]  RemembranceSoule's funeral on April 26, 1865, was attended by a large crowd, with military and civil dignitaries. A journalist described the funeral as "the finest ever seen in this country."[1] In 1867, Soule was posthumously brevetted to the rank of major, in recognition of his meritorious service.[10] Soule was first buried at Denver City Cemetery (now the location of Cheesman Park).[1] A large memorial stone was erected above his grave. The cemetery later closed and burials were transferred in the early 1890s to Riverside Cemetery in Denver. Soule's large memorial stone was not moved with his remains, and he now has a soldier's gravestone in the Grand Army of the Republic section of Riverside Cemetery. His widow is buried in a different section at Riverside Cemetery.[1] From 1998 to 2018 a Spiritual Healing Run/Walk was held in November to honor those killed at Sand Creek. It began at the Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site in southeastern Colorado and concluded on the west steps of the Colorado State Capitol. Starting in 2010, a memorial ceremony was also held at Soule's grave site and at a Denver high-rise building where a memorial plaque honoring Soule was installed near the location of his murder. LegacySoule's name has been proposed as a replacement name for several locations in Colorado. Soule was among the proposed names when Mount Evans was renamed Mount Blue Sky.[11] A creek in Chaffee County (whose name previously included an offensive slur) was renamed Silas Soule Creek.[12] In 2022, it was recommended as a new name for Colorado's Pingree Park, Pingree Road and Pingree Hill after Colorado State University renamed its nearby campus Colorado State University Mountain Campus.[13] See alsoWikimedia Commons has media related to Silas Stillman Soule.

Notes

References

Further readingExternal links

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Portal di Ensiklopedia Dunia