|

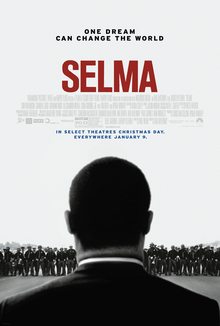

Selma (film)

Selma is a 2014 historical drama film directed by Ava DuVernay and written by Paul Webb. It is based on the 1965 Selma to Montgomery voting rights marches which were initiated and directed by James Bevel[5][6] and led by Martin Luther King Jr., Hosea Williams, and John Lewis. The film stars actors David Oyelowo as King, Tom Wilkinson as President Lyndon B. Johnson, Tim Roth as George Wallace, Carmen Ejogo as Coretta Scott King, and Common as Bevel. Selma premiered at the American Film Institute Festival on November 11, 2014, began a limited US release on December 25, and expanded into wide theatrical release on January 9, 2015, two months before the 50th anniversary of the march. The film was re-released on March 20, 2015 in honor of the 50th anniversary of the historical march. The film was nominated for Best Picture and won Best Original Song at the 87th Academy Awards. It also received four Golden Globe Award nominations, including Best Motion Picture – Drama, Best Director and Best Actor, and won for Best Original Song.[7] PlotIn 1964, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) accepts his Nobel Peace Prize. Four black girls walking down stairs in the Birmingham, Alabama 16th Street Baptist Church are killed by a bomb set by the Ku Klux Klan. Annie Lee Cooper attempts to register to vote in Selma, Alabama, but is prevented by the white registrar. King meets with Lyndon B. Johnson and asks for federal legislation to allow black citizens to register to vote unencumbered, but the president responds that, although he understands Dr. King's concerns, he has more important projects. King travels to Selma with Ralph Abernathy, Andrew Young, James Orange, and Diane Nash. James Bevel greets them, and other SCLC activists appear. FBI director J. Edgar Hoover tells Johnson that King is a problem, and suggests they disrupt his marriage. Coretta Scott King has concerns about her husband's upcoming work in Selma. King calls singer Mahalia Jackson to inspire him with a song. King, other SCLC leaders, and black Selma residents march to the registration office to register. After a confrontation in front of the courthouse, a shoving match occurs as the police go into the crowd. Cooper fights back, knocking Sheriff Jim Clark to the ground, leading to the arrest of Cooper, King, and others. Alabama Governor George Wallace speaks out against the movement. Coretta meets with Malcolm X, who says he will drive whites to ally with King by advocating a more extreme position. Wallace and Al Lingo decide to use force at an upcoming night march in Marion, Alabama, using state troopers to assault the marchers. A group of protesters runs into a restaurant to hide, but troopers rush in and beat and shoot Jimmie Lee Jackson. King and Bevel meet with Cager Lee, Jackson's grandfather, at the morgue. King speaks to ask people to continue to fight for their rights. Harassing phone calls with a recording of sexual activity implied to be King and another woman lead to an argument with Coretta; she knows it is a fabrication, but the strain of constant death threats has taken its toll on her. King is criticized by members of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). As the Selma-to-Montgomery march is about to begin, King talks to Young about delaying it for a day so he can spend some time with his family, but Young convinces King to let the march begin as scheduled without him, saying he can join later. The marchers, including John Lewis of SNCC, Hosea Williams of SCLC, and Selma activist Amelia Boynton, cross the Edmund Pettus Bridge and approach a line of state troopers who put on gas masks. The troopers order the marchers to turn back and, when the marchers hold their ground, the troopers attack with clubs, horses, tear gas, and other weapons. Lewis and Boynton are among those badly injured. The attack is shown on national television and the wounded are treated at Brown Chapel, the movement's headquarter church. Movement attorney Fred Gray asks federal Judge Frank Minis Johnson to let another attempt at the march go forward. President Johnson demands that King and Wallace cease their activities and sends Assistant Attorney General John Doar to convince King to postpone the next march. Numerous white Americans, including Viola Liuzzo, Archbishop Iakovos, and James Reeb, arrive to join the second march. Marchers cross the bridge again and see the state troopers lined up, but the troopers turn aside to let them pass. King, after praying, turns around and leads the group away, which again draws sharp criticism from SNCC activists. That evening, Reeb is beaten to death by an angry white mob on a street in Selma. After a hearing, Judge Johnson approves the march. President Johnson speaks before a Joint Session of Congress to ask for quick passage of a bill to eliminate restrictions on voting, praising the courage of the activists. The march on the highway to Montgomery takes place, and, when the marchers reach Montgomery, King delivers a speech on the steps of the State Capitol. Cast

ProductionDevelopment On June 18, 2008, Variety reported that screenwriter Paul Webb had written an original story about Martin Luther King Jr. and Lyndon B. Johnson for Celador's Christian Colson, which would be co-produced with Brad Pitt's Plan B Entertainment.[31] In 2009, Lee Daniels was reportedly in early talks to direct the film, with financing by Pathé. Dede Gardner and Jeremy Kleiner of Plan B joined as co-producers along with participation of Cloud Eight Films.[32] In 2010, reports indicated that The Weinstein Company would join Pathe and Plan B to finance the $22 million film,[33] but by the next month Daniels had signed on with Sony to re-write and direct The Butler.[34] In an interview in August 2010, Daniels said that financing was there for the Selma project, but he had to choose between The Butler and Selma, and chose The Butler.[35] In July 2013, it was said that Ava DuVernay had signed on to direct the film for Pathé UK and Plan B, and that she was revising the script with the original screenwriter, Paul Webb.[36][37] DuVernay estimated that she re-wrote 90 percent of Webb's original script.[38] Those revisions included rewriting King's speeches, because, in 2009, King's estate licensed them to DreamWorks and Warner Bros. for an untitled project to be produced by Steven Spielberg. Subsequent negotiations between those companies and Selma's producers did not lead to an agreement. DuVernay drafted alternative speeches that evoke the historic ones without violating the copyright. She recalled spending hours listening to King's words while hiking the canyons of Los Angeles. While she did not think she would "get anywhere close to just the beauty and that nuance of his speech patterns", she did identify some of King's basic structure, such as a tendency to speak in triplets (saying one thing in three different ways).[39][40] DuVernay did not receive a screenwriting credit on the finished film due to a stipulation within Webb's original contract that entitled him to the sole credit.[37] In early 2014, Oprah Winfrey came on board as a producer along with Pitt,[41] and by February 25 Paramount Pictures was in final negotiations for the US and Canadian distribution rights.[42] On April 4, 2014, it was announced that Bradford Young would be the director of photography of the film.[43] CastingIn 2010, Daniels (who was the attached director at the time) confirmed that the lead role of King would be played by British actor David Oyelowo. King was one of four main roles played by British actors (the other roles being those of King's wife, President Johnson, and Alabama Governor Wallace).[38] Actors who had confirmed in 2010 but who did not appear in the 2014 production include Robert De Niro, Hugh Jackman, Cedric the Entertainer, Lenny Kravitz, and Liam Neeson.[8][44][45][46][47] On March 26, 2014, British actor Tom Wilkinson was added to the cast to play US President Lyndon B. Johnson.[9] On April 7, it was announced that British actress Carmen Ejogo would play Dr. King's wife, Coretta Scott King.[10] On April 15, actor and rapper Lakeith Stanfield had reportedly joined the cast to play civil rights protester Jimmie Lee Jackson, who was shot and killed on a nighttime march and whose death led James Bevel to initiate the Selma to Montgomery marches.[18][48] On April 22, Lorraine Toussaint joined the cast to portray Amelia Boynton Robinson, who was very active in the Selma movement before SCLC arrived and was the first African-American woman in Alabama to run for Congress.[13] On April 25, it was announced that R&B singer Ledisi had been added to the cast to play Mahalia Jackson, a singer and friend of King.[28] On May 7, Andre Holland joined the cast to play politician and civil rights activist Andrew Young.[11] On May 8, Tessa Thompson was cast to play the role of Diane Nash, a civil rights activist and founding member of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee.[24] On May 9, Deadline confirmed that rapper and actor Common had been cast in the role of James Bevel, the Director of Direct Action and Director of Nonviolent Education of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, who was married to Diane Nash during the events of the film.[16] On May 16, Trai Byers was added to the cast to play James Forman, a civil rights leader active in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee.[26] On June 20, Deadline reported that Colman Domingo had been cast to play SCLC activist Ralph Abernathy.[23] On May 28, Stephan James was confirmed to be portraying the role of SNCC activist John Lewis in the film.[14] On May 29, Wendell Pierce joined the film to play civil rights leader Hosea Williams.[15] On May 30, Cuba Gooding Jr. was set to play civil rights attorney and activist Fred Gray.[19] On June 3, British actor Tim Roth signed on to play Alabama governor George Wallace.[21] On June 4, Niecy Nash joined the cast to play Richie Jean Jackson, a childhood friend of Coretta Scott King and the wife of Dr. Sullivan Jackson (played by Kent Faulcon), while John Lavelle joined to play Roy Reed, a reporter covering the march for The New York Times.[27][29] On June 10, it was announced that the film's producer, Oprah Winfrey, would portray Annie Lee Cooper, a 54-year-old woman who tried to register to vote and was denied by Sheriff Clark—whom she then punched in the jaw and knocked down.[22] Jeremy Strong joined the cast to play James Reeb, a white Unitarian Universalist minister from Boston who was murdered in Selma after the second attempt at the march.[25] On June 12, it was reported that Giovanni Ribisi joined the cast to play Lee C. White, an adviser to Presidents Kennedy and Johnson on strategies regarding the Civil Rights Movement.[12] Alessandro Nivola also joined to play John Doar, a civil rights activist and attorney general for civil rights for the Department of Justice in the 1960s.[17] Dylan Baker was added to the cast on July 17 to play FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover, who carried out extensive investigations of King and his associates.[20] Filming Principal photography began May 20, 2014, around Atlanta, Georgia.[49][50] Filming took place around Marietta Square[51] and Rockdale County Courthouse in Conyers. The Conyers scene involved a portrayal of federal judge Frank Minis Johnson, who ruled that the third and final march could go forward.[52] In Newton County, Georgia, filming took place at Flat Road, Airport Road, Gregory Road, Conyers, Brown, Ivy and Emory Streets, exteriors on Lee Street, outside shots of the old Newton County Courthouse, shots of the Covington Square, and an interior night shoot at the Townhouse Café on Washington St.[53] In Alabama, scenes were shot in Selma, centering on the Bloody Sunday march to the Edmund Pettus Bridge, and in Montgomery, Alabama, where, in 1965, King led civil rights demonstrators down Dexter Avenue toward the Alabama State Capitol at the conclusion of the third march from Selma.[54] MusicJason Moran composed the music for the film, marking his debut in the field.[55] Common (who plays James Bevel) and John Legend released the accompanying track "Glory" in December 2014, ahead of the film's theatrical release. A protest anthem, "Glory" refers to the 2014 Ferguson protests and earned both the Golden Globe Award for Best Original Song[56][57] and the Academy Award for Best Original Song.[58] The soundtrack album Selma: Music from the Motion Picture was released digitally on December 23, 2014 and physically on January 13, 2015.[59] Among the other songs featured in the film was a 1970 cover of a Mahalia Jackson song 'Walk With Me Lord' cover by Martha Bass and the Harold Smith Majestics Choir. ReleaseSelma premiered in Los Angeles at Grauman's Egyptian Theatre during AFI Fest on November 11, 2014,[60] after which it received a standing ovation.[61] It opened in limited release in the United States on December 25, 2014, including in Los Angeles, New York City, and Atlanta,[62] before its wide opening on January 9, 2015.[63] The film was screened in the Berlinale Special Galas section of the 65th Berlin International Film Festival in February 2015.[64] It was released by Pathé and their distribution partner 20th Century Fox on February 6, 2015, in the United Kingdom. Paramount Pictures gave the film a limited re-release in the US on March 20, 2015, to honor the historical march's 50th anniversary, and another re-release in January 2021 to celebrate Black History Month.[65] Selma was released on Blu-ray and DVD on April 14, 2015. ReceptionCritical responseSelma received critical acclaim, with particular praise given to DuVernay's direction and Oyelowo's performance, though it was met with some criticism for its historical inaccuracies, which largely centered on the perceived vilification of Johnson and the omission of several prominent Jewish civil rights leaders.[66] On Rotten Tomatoes, the film holds an approval rating of 99% based on 314 reviews, with an average rating of 8.5/10; the site's critical consensus reads: "Fueled by a gripping performance from David Oyelowo, Selma draws inspiration and dramatic power from the life and death of Martin Luther King Jr. – but doesn't ignore how far we remain from the ideals his work embodied."[67] On Metacritic, the film has a score of 79 out of 100, based on 52 critics, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[68] Audiences polled by CinemaScore gave the film a rare grade of "A+" on an A+ to F scale.[69][70][71] Richard Roeper of The Chicago Sun Times praised the film as "an important history lesson that never feels like a lecture. Once school is back in session, every junior high school class in America should take a field trip to see this movie."[72] Joe Morgenstern, writing for The Wall Street Journal, wrote: "At its best, Ava DuVernay's biographical film honors Dr. King's legacy by dramatizing the racist brutality that spurred him and his colleagues to action."[73] A. O. Scott of The New York Times praised the acting, directing, writing, and cinematography, and wrote: "Even if you think you know what's coming, Selma hums with suspense and surprise. Packed with incident and overflowing with fascinating characters, it is a triumph of efficient, emphatic cinematic storytelling."[74] Rene Rodriguez, writing in the Miami Herald, commented that:

Peter Travers of Rolling Stone wrote: "DuVernay's look at Martin Luther King's 1965 voting-rights march against racial injustice stings with relevance to the here and now. Oyelowo's stirring, soulful performance as King deserves superlatives."[76] David Denby, writing for The New Yorker, wrote: "This is cinema, more rhetorical, spectacular, and stirring than cable-TV drama."[77] Ann Hornaday of The Washington Post gave the film four out of five stars, and wrote: "With Selma, director Ava DuVernay has created a stirring, often thrilling, uncannily timely drama that works on several levels at once ... she presents [Martin Luther King Jr.] as a dynamic figure of human-scale contradictions, flaws and supremely shrewd political skills."[78] Praise was not unanimous; writing about why Selma was not nominated for more Academy Awards, Adolph Reed Jr., political science professor at the University of Pennsylvania, opined that "now it's the black (haute) bourgeoisie that suffers injustice on behalf of the black masses."[79] AccoladesThe film won and was nominated for several awards in 2014–15. Historical accuracyThe historical accuracy of Selma's story has been the subject of controversy about the degree to which artistic license should be used in historical fiction.[80][81] The film was criticized by some for its omission of various individuals and groups historically associated with the Selma marches, while others challenged how particular historical figures in the script were represented. Most controversy in the media centered on the film's portrayal of President Johnson and his relationship with King. According to people such as LBJ Presidential Library director Mark Updegrove[82] and Joseph A. Califano Jr., Johnson was a champion of civil rights legislation and a proactive partner of King, and they accused the film of falsely depicting Johnson as a reluctant, obstructionist political actor who had the FBI monitor and harass King.[83][84] Having served as Johnson's top domestic policy assistant (including on issues of civil rights) and as U.S. Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare, Califano questioned whether the writer and director felt "free to fill the screen with falsehoods, immune from any responsibility to the dead, just because they thought it made for a better story".[85] Historian David E. Kaiser said that the film's depiction of Johnson as obstructing Dr. King's civil rights efforts—when, in fact, he helped get important legislation passed—advances a false narrative that American whites are "hopelessly infected by racism and that black people could and should depend only on themselves".[86] Andrew Young—SCLC activist and official, and later U.S. congressman, ambassador to the United Nations, and mayor of Atlanta—told The Washington Post that the depiction of the relationship between Johnson and King "was the only thing I would question in the movie. Everything else, they got 100 percent right". According to Young, the two were always mutually respectful, and King respected Johnson's political problems.[87] On television, Young pointed out that it was US Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy who had signed the order that allowed the FBI to monitor King and other SCLC members and that it happened before Johnson took office.[88] Some Jews who marched with King at Selma wrote that the film omits any mention of the Jews who contributed significantly to the civil rights movement, effectively "airbrushing" Jews out of the film, particularly Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel, who appeared in news photos at the front of the march with King.[89][90][91] Director DuVernay and US Representative John Lewis, who is portrayed in the film marching with King during the civil rights movement, responded separately that the film Selma is a work of art about the people of Selma, not a documentary. DuVernay said in an interview that she did not see herself as "a custodian of anyone's legacy".[92] In response to criticisms that she rewrote history to portray her own agenda, DuVernay said that the movie is "not a documentary. I'm not a historian. I'm a storyteller."[93] Lewis wrote in an op-ed for The Los Angeles Times: "We do not demand completeness of other historical dramas, so why is it required of this film?"[94] In a scene-by-scene analysis, the visual blog Information is Beautiful gave Selma a score of 100%, noting: "This movie painstakingly recreates events as they happened".[95] See also

References

External links

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||