|

Emmett Till

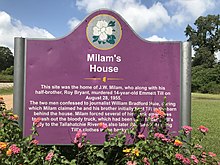

Emmett Louis Till (July 25, 1941 – August 28, 1955) was a 14-year-old African American youth who was abducted and lynched in Mississippi in 1955 after being accused of offending a white woman, Carolyn Bryant, in her family's grocery store. The brutality of his murder and the acquittal of his killers drew attention to the long history of violent persecution of African Americans in the United States. Till posthumously became an icon of the civil rights movement.[2] Till was born and raised in Chicago, Illinois. During summer vacation in August 1955, he was visiting relatives near Money, Mississippi, in the Mississippi Delta region. Till spoke to 21-year-old Carolyn Bryant, the white, married proprietor of a local grocery store. Although what happened at the store is a matter of dispute, Till was accused of flirting with, touching, or whistling at Bryant. Till's interaction with Bryant, perhaps unwittingly, violated the unwritten code of behavior for a black male interacting with a white female in the Jim Crow-era South.[3] Several nights after the encounter, Bryant's husband Roy and his half-brother J. W. Milam, who were armed, went to Till's great-uncle's house and abducted Till, age 14. They beat and mutilated him before shooting him in the head and sinking his body in the Tallahatchie River. Three days later, Till's mutilated and bloated body was discovered and retrieved from the river. Till's body was returned to Chicago, where his mother insisted on a public funeral service with an open casket, which was held at Roberts Temple Church of God in Christ.[4] It was later said that "The open-coffin funeral held by Mamie Till Bradley[a] exposed the world to more than her son Emmett Till's bloated, mutilated body. Her decision focused attention on not only American racism and the barbarism of lynching but also the limitations and vulnerabilities of American democracy."[5] Tens of thousands attended his funeral or viewed his open casket, and images of Till's mutilated body were published in black-oriented magazines and newspapers, rallying popular black support and white sympathy across the United States. Intense scrutiny was brought to bear on the lack of black civil rights in Mississippi, with newspapers around the U.S. critical of the state. Although local newspapers and law enforcement officials initially decried the violence against Till and called for justice, they responded to national criticism by defending Mississippians, giving support to the killers. In September 1955, an all-white jury found Bryant and Milam not guilty of Till's murder. Protected against double jeopardy, the two men publicly admitted in a 1956 interview with Look magazine that they had tortured and murdered Till, selling the story of how they did it for $4,000 (equivalent to $45,000 in 2023).[6] Till's murder was seen as a catalyst for the next phase of the civil rights movement. In December 1955, the Montgomery bus boycott began in Alabama and lasted more than a year, resulting eventually in a U.S. Supreme Court ruling that segregated buses were unconstitutional. According to historians, events surrounding Till's life and death continue to resonate. An Emmett Till Memorial Commission was established in the early 21st century. The county courthouse in Sumner was restored and includes the Emmett Till Interpretive Center. 51 sites in the Mississippi Delta are memorialized as associated with Till. The Emmett Till Antilynching Act, an American law which makes lynching a federal hate crime, was signed into law on March 29, 2022, by President Joe Biden.[7] Early childhoodEmmett Till was born to Mamie and Louis Till on July 25, 1941, in Chicago. Emmett's mother, Mamie, was born in the small Delta town of Webb, Mississippi. The Delta region encompasses the large, multi-county area of northwestern Mississippi in the watershed of the Yazoo and Mississippi rivers. When Carthan was two years old, her family moved to Argo, Illinois, near Chicago, as part of the Great Migration of rural black families out of the South to the North to escape violence, lack of opportunity and unequal treatment under the law.[8] Argo received so many Southern migrants that it was named "Little Mississippi"; Carthan's mother's home was often used by other recent migrants as a way station while they were trying to find jobs and housing.[9] Mississippi was the poorest state in the U.S. in the 1950s, and the Delta counties were some of the poorest in Mississippi.[9] Mamie Carthan was born in Tallahatchie County, where the average income per white household in 1949 was $690 (equivalent to $8,800 in 2023). For black families, the figure was $462 (equivalent to $5,900 in 2023).[10] In the rural areas, economic opportunities for blacks were almost nonexistent. They were mostly sharecroppers who lived on land owned by whites. Blacks had essentially been disenfranchised and excluded from voting and the political system since 1890 when the white-dominated legislature passed a new constitution that raised barriers to voter registration. Whites had also passed ordinances establishing racial segregation and Jim Crow laws. Mamie largely raised Emmett with her mother; she and Louis Till separated in 1942 after Mamie discovered that he had been unfaithful. Louis later assaulted Mamie, choking her to unconsciousness, to which she responded by throwing scalding water at him.[11] For violating court orders to stay away from Mamie, Louis Till was forced by a judge in 1943 to choose between jail or enlisting in the U.S. Army. In 1945, a few weeks before his son's fourth birthday, Louis Till was court-martialed and executed in Italy for the murder of an Italian woman and the rape of two others.[12][13] At the age of six, Emmett contracted polio, which left him with a persistent stutter.[14] Mamie and Emmett moved to Detroit, where she met and married "Pink" Bradley in 1951. Emmett preferred living in Chicago, so he returned there to live with his grandmother; his mother and stepfather rejoined him later that year. After the marriage dissolved in 1952, "Pink" Bradley returned alone to Detroit.[15]  Mamie Till-Bradley and Emmett lived together in a busy neighborhood in Chicago's South Side near distant relatives. She began working as a civilian clerk for the U.S. Air Force for a better salary. She recalled that Till was industrious enough to help with chores at home, although he sometimes got distracted. Till's mother remembered that he did not know his own limitations at times. Following the couple's separation, Bradley visited Mamie and began threatening her. At 11 years old, Till, with a butcher knife in hand, told Bradley he would kill him if the man did not leave.[17] Till was typically happy, however. He and his cousins and friends pulled pranks on each other (Till once took advantage of an extended car ride when his friend fell asleep and placed the friend's underwear on his head), and they also spent their free time in pickup baseball games. Till was a smart dresser,[18] and was often the center of attention among his peers.[19] Plans to visit relatives in MississippiIn 1955, Mamie Till-Bradley's uncle, 64-year-old Mose Wright, visited her and Emmett in Chicago during the summer and told him stories about living in the Mississippi Delta. Emmett wanted to see for himself. Wright planned to accompany Till with a cousin, Wheeler Parker; another cousin, Curtis Jones, would join them soon after. Wright was a sharecropper and part-time minister who was often called "Preacher".[20] He lived in Money, Mississippi, a small town in the Delta that consisted of three stores, a school, a post office, a cotton gin, and a few hundred residents, 8 miles (13 km) north of Greenwood. Before Till departed for the Delta, his mother cautioned him that Chicago and Mississippi were two different worlds, and he should know how to behave in front of white people in the South.[21] Till assured her that he understood.[22] Statistics on lynchings began to be collected in 1882. Since that time, more than 500 African Americans have been killed by extrajudicial violence in Mississippi alone, and more than 3,000 across the South.[23] Most of the incidents took place between 1876 and 1930; though far less common by the mid-1950s, these racially motivated murders still occurred. Throughout the South, interracial relationships were prohibited as a means to maintain white supremacy.[24] Even the suggestion of sexual contact between black men and white women could carry severe penalties for black men. A resurgence of the enforcement of such Jim Crow laws was evident following World War II, when African-American veterans started pressing for equal rights in the South.[25] Racial tensions increased after the United States Supreme Court's 1954 decision in Brown v. Board of Education to end segregation in public education, which it ruled unconstitutional. Many segregationists believed the ruling would lead to interracial dating and marriage. Whites strongly resisted the court's ruling; one Virginia county closed all its public schools to prevent integration. Other jurisdictions simply ignored the ruling. In other ways, whites used stronger measures to keep blacks politically disenfranchised, which they had been since the turn of the century. Segregation in the South was used to constrain blacks forcefully from any semblance of social equality.[26] A week before Till arrived in Mississippi, a black activist named Lamar Smith was shot and killed in front of the county courthouse in Brookhaven for political organizing. Three white suspects were arrested, but they were soon released.[27] Encounter between Till and Carolyn Bryant  Till arrived at the home of Mose and Elizabeth Wright in Money, Mississippi, on August 21, 1955. On the evening of August 24, Till and several young relatives and neighbors were driven by his cousin Maurice Wright to Bryant's Grocery and Meat Market to buy candy. Till's companions were children of sharecroppers and had been picking cotton all day. The market mostly served the local sharecropper population and was owned by a white couple, 24-year-old Roy Bryant and his 21-year-old wife Carolyn.[28] The facts of what took place in the store are still disputed. Journalist William Bradford Huie reported that Till showed the youths outside the store a photograph of a white girl in his wallet, and bragged that she was his girlfriend.[29] Till's cousin Curtis Jones said the photograph was of an integrated class at the school Till attended in Chicago.[b] According to Huie and Jones, one or more of the local boys then dared Till to speak to Bryant.[28] However, in his 2009 book, Till's cousin Simeon Wright, who was present, disputed the accounts of Huie and Jones. According to Wright, Till did not have a photo of a white girl, and nobody dared him to flirt with Bryant.[33] Speaking in 2015, Wright said: "We didn't dare him to go to the store—the white folk said that. They said that he had pictures of his white girlfriend. There were no pictures. They never talked to me. They never interviewed me."[34] The FBI report completed in 2006 notes: "[Curtis] Jones recanted his 1955 statements prior to his death and apologized to Mamie Till-Mobley".[35][c] According to both Simeon Wright and Wheeler Parker,[40] Till wolf-whistled at Bryant. Wright said, "I think [Emmett] wanted to get a laugh out of us or something," adding, "He was always joking around, and it was hard to tell when he was serious." Wright stated that following the whistle, he became immediately alarmed. "Well, it scared us half to death," Wright recalled. "You know, we were almost in shock. We couldn't get out of there fast enough, because we had never heard of anything like that before. A black boy whistling at a white woman? In Mississippi? No." Wright stated "The Ku Klux Klan and night riders were part of our daily lives".[33][41] Following his disappearance, a newspaper account stated that Till sometimes whistled to alleviate his stuttering.[42] His speech was sometimes unclear; Mamie said he had particular difficulty with pronouncing "b" sounds, and he may have whistled to overcome problems asking for bubble gum.[43][44][45] She said that, to help with his articulation, Mamie taught Till how to whistle softly to himself before pronouncing his words.[44] During the murder trial,[d] Bryant testified that Till grabbed her hand while she was stocking candy and said, "How about a date, baby?"[46][29] Bryant said that after she freed herself from his grasp, Till followed her to the cash register,[46] grabbed her waist and said, "What's the matter baby, can't you take it?"[46][e] Bryant said she freed herself, and Till said, "You needn't be afraid of me, baby",[46] used "one 'unprintable' word"[46] and said "I've been with white women before."[46][47] Bryant also alleged that one of Till's companions came into the store, grabbed him by the arm, and ordered him to leave.[46] According to historian Timothy Tyson, Bryant admitted to him in a 2008 interview that her testimony during the trial that Till had made verbal and physical advances was false.[48][49][50] Bryant had testified Till grabbed her waist and uttered obscenities but later told Tyson, "that part's not true."[51] As for the rest of what happened, the 72-year-old stated she could not remember.[52] Bryant is quoted by Tyson as saying, "Nothing that boy did could ever justify what happened to him."[53] However, the tape recordings that Tyson made of the interviews with Bryant do not contain Bryant saying this. In addition, Bryant's daughter-in-law, who was present during Tyson's interviews, says that Bryant never said it.[54][55] Decades later, Simeon Wright also challenged the account given by Carolyn Bryant at the trial.[56] Wright claims he entered the store "less than a minute" after Till was left inside alone with Bryant,[56] and he saw no inappropriate behavior and heard "no lecherous conversation."[56] Wright said Till "paid for his items and we left the store together."[56] In their 2006 investigation of the cold case, the FBI noted that a second anonymous source, who was confirmed to have been in the store at the same time as Till and his cousin, supported Wright's account.[35] Author Devery Anderson writes that in an interview with the defense's attorneys, Bryant told a version of the initial encounter that included Till grabbing her hand and asking her for a date, but not Till approaching her and grabbing her waist, mentioning past relationships with white women, or having to be dragged unwillingly out of the store by another boy. Anderson further notes that many remarks prior to Till's kidnapping made by those involved indicate that it was his remarks to Bryant that angered his killers, rather than any alleged physical harassment. For instance, Mose Wright (a witness to the kidnapping) said that the kidnappers mentioned only "talk" at the store, and Sheriff George Smith only spoke of the arrested killers accusing Till of "ugly remarks." Anderson suggests that this evidence taken together implies that the more extreme details of Bryant's story were invented after the fact as part of the defense's legal strategy.[57] After Wright and Till left the store, Bryant went outside to retrieve a pistol from underneath the seat of a car. Till and his companions saw her do this and left immediately.[47] It was acknowledged that Till whistled while Bryant was going to her car.[35] However, one witness, Roosevelt Crawford, maintained that Till's whistle was directed not at Bryant, but at the checkers game that was taking place outside the store.[58] Carolyn's husband, Roy Bryant, was on an extended trip hauling shrimp to Texas and did not return home until August 27.[59] Historian Timothy Tyson said an investigation by civil rights activists concluded Carolyn Bryant did not initially tell her husband Roy Bryant about the encounter with Till, and that Roy was told by a person who frequented their store.[60] Roy was reportedly angry at his wife for not telling him. Carolyn Bryant told the FBI she did not tell her husband because she feared he would assault Till.[61] Lynching

When Roy Bryant was informed of what had happened, he aggressively questioned several young black men who entered the store. That evening, Bryant, with a black man named J. W. Washington, approached a black teenager walking along a road. Bryant ordered Washington to seize the boy, put him in the back of a pickup truck, and took him to be identified by a companion of Carolyn's who had witnessed the episode with Till. Friends or parents vouched for the boy in Bryant's store, and Carolyn's companion denied that the boy Bryant and Washington seized was the one who had accosted her. Somehow, Bryant learned that the boy in the incident was from Chicago and was staying with Mose Wright.[h] Several witnesses overheard Bryant and his 36-year-old half-brother, John William "J. W." Milam, discussing taking Till from his house.[67] In the early morning hours of August 28, 1955, sometime between 2:00 and 3:30 a.m., Bryant and Milam drove to Mose Wright's house. Armed with a pistol and a flashlight, he asked Wright if he had three boys in the house from Chicago. Till was sharing a bed with another cousin and there were a total of eight people in the cabin.[36]: 26 [68] Milam asked Wright to take them to "the nigger who did the talking." Till's great-aunt offered the men money, but Milam refused as he rushed Emmett to put on his clothes. Mose Wright informed the men that Till was from up north and did not know any better. Milam reportedly then asked, "How old are you, preacher?" to which Wright responded, "64." Milam threatened that if Wright told anybody, he would not live to see 65. The men marched Till out to the truck. Wright said he heard them ask someone in the car if this was the boy, and heard someone say "yes." When asked if the voice was that of a man or a woman Wright said that "it seemed like it was a lighter voice than a man's."[69] In a 1956 interview with Look magazine, in which they confessed to the killing, Bryant and Milam said they would have brought Till by the store in order to have Carolyn identify him, but stated they did not do so because they said Till admitted to being the one who had talked to her.[29] Milam and Bryant tied up Till in the back of a green pickup truck and drove toward Money, Mississippi. According to some witnesses, they took Till back to Bryant's Groceries and recruited two black men. The men then drove to a barn in Drew, pistol-whipping Till on the way and reportedly knocked him unconscious. Willie Reed, who was 18 years old at the time, saw the truck passing by and later recalled seeing two white men in the front seat, and "two black males" in the back.[70] Some have speculated that the two black men worked for Milam and were forced to help with the beating, although they later denied being present.[71][72] Willie Reed said that while walking home, he heard the beating and crying from the barn. Reed told a neighbor and they both walked back up the road to a water well near the barn, where they were approached by Milam. Milam asked if they heard anything. Reed responded, "No." Others passed by the shed and heard yelling. A local neighbor also spotted "Too Tight" (Leroy Collins) at the back of the barn washing blood off the truck and noticed Till's boot. Milam explained he had killed a deer and that the boot belonged to him.[citation needed] Some have claimed that Till was shot and tossed over the Black Bayou Bridge in Glendora, Mississippi, near the Tallahatchie River.[73] The group drove back to Roy Bryant's home in Money, where they reportedly burned Till's clothes.

—J. W. Milam, Look magazine, 1956[29]

In an interview with William Bradford Huie that was published in Look magazine in 1956, Bryant and Milam said that they intended to beat Till and throw him off an embankment into the river to frighten him. They told Huie that while they were beating Till, he called them bastards, declared he was as good as they and said that he had sexual encounters with white women. They put Till in the back of their truck, and drove to a cotton gin to take a 70-pound (32 kg) fan—the only time they admitted to being worried, thinking that by this time in early daylight they would be spotted and accused of stealing—and drove for several miles along the river looking for a place to dispose of Till. They shot him by the river and weighted his body with the fan.[29][i] Mose Wright stayed on his front porch for 20 minutes waiting for Till to return. He did not go back to bed. Wright and another man went into Money, got gasoline, and drove around unsuccessfully trying to find Till. They had returned home by 8:00 a.m.[74] After hearing from Wright that he would not call the police because he feared for his life, Curtis Jones placed a call to the Leflore County sheriff, and another to his mother in Chicago. Distraught, she called Emmett's mother Mamie Till-Bradley.[75] Wright and his wife Elizabeth drove to Sumner, where Elizabeth's brother contacted the sheriff.[76] Bryant and Milam were questioned by Leflore County sheriff George Smith. They admitted they had taken the boy from his great-uncle's yard, but claimed they had released him the same night in front of Bryant's store. Bryant and Milam were arrested for kidnapping.[77] Word got out that Till was missing, and soon Medgar Evers, Mississippi state field secretary for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), and Amzie Moore, head of the NAACP's Bolivar County chapter, became involved. They disguised themselves as cotton pickers and went into the cotton fields in search of any information that might help find Till.[78] Three days after his abduction and murder, Till's swollen and disfigured body was found by two boys who were fishing in the Tallahatchie River. His head was very badly mutilated: he had been shot above the right ear, an eye was dislodged from the socket, there was evidence that he had been beaten on the back and the hips, and his body weighted by a fan blade fastened around his neck with barbed wire. Till was nude, but wearing a silver ring with the initials "L. T." and "May 25, 1943" carved in it.[79][j] His face was unrecognizable due to trauma and having been submerged in water. Mose Wright was called to the river to identify Till. The silver ring that Till was wearing was removed, returned to Wright, and passed on to the district attorney as evidence. Funeral and reaction Although lynchings and racially motivated murders had occurred throughout the South for decades, the circumstances surrounding Till's murder and the timing acted as a catalyst to attract national attention to the case of a 14-year-old boy who had allegedly been killed for breaching a social caste system. Till's murder aroused feelings about segregation, law enforcement, relations between the North and South, the social status quo in Mississippi, the activities of the NAACP and the White Citizens' Councils, and the Cold War, all of which were played out in a drama staged in newspapers all over the U.S. and abroad.[80] After Till went missing, a three-paragraph story was printed in The Greenwood Commonwealth and quickly picked up by other Mississippi newspapers. They reported on his death when the body was found. The next day, when a picture of him his mother had taken the previous Christmas showing them smiling together appeared in the Jackson Daily News and Vicksburg Evening Post, editorials and letters to the editor were printed expressing shame at the people who had caused Till's death. One read, "Now is the time for every citizen who loves the state of Mississippi to 'Stand up and be counted' before hoodlum white trash brings us to destruction." The letter said that Negroes were not the downfall of Mississippi society, but whites like those in White Citizens' Councils that condoned violence.[81] Till's body was clothed, packed in lime, placed into a pine coffin, and prepared for burial. It may have been embalmed while in Mississippi. Mamie Till-Bradley demanded that the body be sent to Chicago; she later said that she worked to halt an immediate burial in Mississippi and called several local and state authorities in Illinois and Mississippi to make sure that her son was returned to Chicago.[82] A doctor did not examine Till post-mortem.[83] Mississippi's governor, Hugh L. White, deplored the murder, asserting that local authorities should pursue a "vigorous prosecution." He sent a telegram to the national offices of the NAACP, promising a full investigation and assuring them "Mississippi does not condone such conduct." Delta residents, both black and white, also distanced themselves from Till's murder, finding the circumstances abhorrent. Local newspaper editorials denounced the murderers without question.[47][84] Leflore County Deputy Sheriff John Cothran stated, "The white people around here feel pretty mad about the way that poor little boy was treated, and they won't stand for this."[85] However, discourse about Till's murder soon became more complex. Robert B. Patterson, executive secretary of the segregationist White Citizens' Council, used Till's death to claim that racial segregation policies were to provide for blacks' safety and that their efforts were being neutralized by the NAACP. In response, NAACP executive secretary Roy Wilkins characterized the incident as a lynching and said that Mississippi was trying to maintain white supremacy through murder. He said, "there is in the entire state no restraining influence of decency, not in the state capital, among the daily newspapers, the clergy, nor any segment of the so-called better citizens."[86] Mamie Till-Bradley told a reporter that she would seek legal aid to help law enforcement find her son's killers and that the State of Mississippi should share the financial responsibility. She was misquoted; it was reported as "Mississippi is going to pay for this."[87]  The A. A. Rayner Funeral Home in Chicago received Till's body. Upon arrival, Bradley insisted on viewing it to make a positive identification, later stating that the stench from it was noticeable two blocks away.[88] She decided to have an open-casket funeral, saying: "There was just no way I could describe what was in that box. No way. And I just wanted the world to see."[78] Tens of thousands of people lined the street outside the mortuary to view Till's body, and days later thousands more attended his funeral at Roberts Temple Church of God in Christ.  Photographs of Till's mutilated corpse circulated around the country, notably appearing in Jet magazine and The Chicago Defender, both black publications, generating intense public reaction. According to The Nation and Newsweek, Chicago's black community was "aroused as it has not been over any similar act in recent history".[89][k] Time later selected one of the Jet photographs showing Mamie Till over the mutilated body of her dead son, as one of the 100 "most influential images of all time": "For almost a century, African Americans were lynched with regularity and impunity. Now, thanks to a mother's determination to expose the barbarousness of the crime, the public could no longer pretend to ignore what they couldn't see."[90] On September 6, Till was buried at Burr Oak Cemetery in Alsip, Illinois.[91] News about Emmett Till spread to both coasts. Chicago Mayor Richard J. Daley and Illinois Governor William Stratton also became involved, urging Mississippi Governor White to see that justice was done. The tone in Mississippi newspapers changed dramatically. They falsely reported riots in the funeral home in Chicago. Bryant and Milam appeared in photos smiling and wearing military uniforms,[92] and Carolyn Bryant's beauty and virtue were extolled. Rumors of an invasion of outraged blacks and northern whites were printed throughout the state, and were taken seriously by the Leflore County Sheriff. T. R. M. Howard, a local businessman, surgeon, and civil rights proponent and one of the wealthiest black people in the state, warned of a "second civil war" if "slaughtering of Negroes" were allowed.[93] Following Roy Wilkins' comments, white opinion began to shift. According to historian Stephen J. Whitfield, a specific brand of xenophobia in the South was particularly strong in Mississippi. Whites were urged to reject the influence of Northern opinion and agitation.[94] This independent attitude was profound enough in Tallahatchie County that it earned the nickname "The Freestate of Tallahatchie", according to a former sheriff, "because people here do what they damn well please", making the county often difficult to govern.[95] Tallahatchie County Sheriff Clarence Strider, who initially positively identified Till's body and stated that the case against Milam and Bryant was "pretty good", on September 3 announced his doubts that the body pulled from the Tallahatchie River was that of Till. He speculated that the boy was probably still alive. Strider suggested that the recovered body had been planted by the NAACP: a corpse stolen by T. R. M. Howard, who colluded to place Till's ring on it.[96] Strider changed his account after comments were published in the press denigrating the people of Mississippi, later saying: "The last thing I wanted to do was to defend those peckerwoods. But I just had no choice about it."[47][l] Bryant and Milam were indicted for murder. The state's prosecuting attorney, Hamilton Caldwell, was not confident that he could get a conviction in a case of white violence against a black male accused of insulting a white woman. A local black paper was surprised at the indictment and praised the decision, as did The New York Times. The high-profile comments published in Northern newspapers and by the NAACP were of concern to the prosecuting attorney, Gerald Chatham; he worried that his office would not be able to secure a guilty verdict, despite the compelling evidence. Having limited funds, Bryant and Milam initially had difficulty finding attorneys to represent them, but five attorneys at a Sumner law firm offered their services pro bono.[94] Their supporters placed collection jars in stores and other public places in the Delta, eventually gathering $10,000 for the defense (about $114,500 in 2023).[98] TrialThe trial was held in the county courthouse in Sumner, the western seat of Tallahatchie County, because Till's body was found in this area. Sumner had one boarding house; the small town was besieged by reporters from all over the country. David Halberstam called the trial "the first great media event of the civil rights movement".[99] A reporter who had covered the trials of Bruno Hauptmann and Machine Gun Kelly remarked that this was the most publicity for any trial he had ever seen.[47] No hotels were open to black visitors. Mamie Till-Bradley arrived to testify, and the trial also attracted black congressman Charles Diggs from Michigan. Bradley, Diggs, and several black reporters stayed at T. R. M. Howard's home in Mound Bayou. Located on a large lot and surrounded by Howard's armed guards, it resembled a compound. The day before the start of the trial, a young black man named Frank Young arrived to tell Howard he knew of two witnesses to the crime. Levi "Too Tight" Collins and Henry Lee Loggins were black employees of Leslie Milam, J. W.'s brother, in whose shed Till was beaten. Collins and Loggins were spotted with J. W. Milam, Bryant, and Till. The prosecution team was unaware of Collins and Loggins. Sheriff Strider, however, booked them into the Charleston, Mississippi, jail to keep them from testifying.[100] The trial was held in September 1955 and lasted for five days; attendees remembered that the weather was very hot. The courtroom was filled to capacity with 280 spectators; black attendees sat in segregated sections.[101] Press from major national newspapers attended, including black publications; black reporters were required to sit in the segregated black section and away from the white press, farther from the jury. Sheriff Strider welcomed black spectators coming back from lunch with a cheerful, "Hello, Niggers!"[102] Some visitors from the North found the court to be run with surprising informality. Jury members were allowed to drink beer on duty, and many white male spectators wore handguns.[103]  The defense sought to cast doubt on the identity of the body pulled from the river. They said it could not be positively identified, and they questioned whether Till was dead at all. The defense also asserted that although Bryant and Milam had taken Till from his great-uncle's house, they had released him that night. The defense attorneys attempted to prove that Mose Wright—who was addressed as "Uncle Mose" by the prosecution and "Mose" by the defense[106]—could not identify Bryant and Milam as the men who took Till from his cabin. They noted that only Milam's flashlight had been in use that night, and no other lights in the house were turned on. Milam and Bryant had identified themselves to Wright the evening they took Till; Wright said he had only seen Milam clearly. Wright's testimony was considered remarkably courageous. It may have been the first time in the South that a black man had testified to the guilt of a white man in court—and lived.[107] Journalist James Hicks, who worked for the black news wire service, the National Negro Publishers Association (later renamed the National Newspaper Publishers Association), was present in the courtroom; he was especially impressed that Wright stood to identify Milam, pointing to him and saying "There he is",[m] calling it a historic moment and one filled with "electricity".[108] A writer for the New York Post noted that following his identification, Wright sat "with a lurch which told better than anything else the cost in strength to him of the thing he had done".[109] A reporter who covered the trial for the New Orleans Times-Picayune said it was "the most dramatic thing I saw in my career".[110] Mamie Till-Bradley testified that she had instructed her son to watch his manners in Mississippi and that should a situation ever come to his being asked to get on his knees to ask forgiveness of a white person, he should do it without a thought. The defense questioned her identification of her son in the casket in Chicago and a $400 life insurance policy she had taken out on him (equivalent to $4,500 in 2023).[111] While the trial progressed, Leflore County Sheriff George Smith, Howard, and several reporters, both black and white, attempted to locate Collins and Loggins. They could not, but found three witnesses who had seen Collins and Loggins with Milam and Bryant on Leslie Milam's property. Two of them testified that they heard someone being beaten, blows, and cries.[111] One testified so quietly the judge ordered him several times to speak louder; he said he heard the victim call out: "Mama, Lord have mercy. Lord have mercy."[112] Sheriff Strider testified for the defense of his theory that Till was alive and that the body retrieved from the river was white. A doctor from Greenwood stated on the stand that the body was too decomposed to identify, and therefore had been in the water too long for it to be Till.[9] Carolyn Bryant was allowed to testify in court, but because Judge Curtis Swango ruled in favor of the prosecution's objection that her testimony was irrelevant to Till's abduction and murder, the jury was not present.[9][57][113] In the event that the defendants were convicted, the defense wanted her testimony on record to aid in a possible appeal.[114] In the concluding statements, one prosecuting attorney said that what Till did was wrong, but that his action warranted a spanking, not murder. Gerald Chatham passionately called for justice and mocked the sheriff and doctor's statements that alluded to a conspiracy. Mamie Bradley indicated she was very impressed with his summation.[115] The defense stated that the prosecution's theory of the events the night Till was murdered was improbable, and said the jury's "forefathers would turn over in their graves" if they convicted Bryant and Milam. Only three outcomes were possible in Mississippi for capital murder: life imprisonment, the death penalty, or acquittal. On September 23 the all-white, all-male jury (both women and blacks had been banned)[116] acquitted both Milam and Bryant after a 67-minute deliberation; one juror said, "If we hadn't stopped to drink pop, it wouldn't have taken that long."[117][n] In post-trial analyses, the blame for the outcome varied. Mamie Till-Bradley was criticized for not crying enough on the stand. The jury was noted to have been picked almost exclusively from the hill country section of Tallahatchie County, which, due to its poorer economic make-up, found whites and blacks competing for land and other agrarian opportunities. Unlike the population living closer to the river (and thus closer to Bryant and Milam in Leflore County), who possessed a noblesse oblige outlook toward blacks, according to historian Stephen Whitaker, those in the eastern part of the county were virulent in their racism. The prosecution was criticized for dismissing any potential juror who knew Milam or Bryant personally, for fear that such a juror would vote to acquit. Afterward, Whitaker noted that this had been a mistake, as those who knew the defendants usually disliked them.[47][115] One juror voted twice to convict, but on the third discussion, voted with the rest of the jury to acquit.[118] In later interviews, the jurors acknowledged that they knew Bryant and Milam were guilty, but simply did not believe that life imprisonment or the death penalty were fit punishment for whites who had killed a black man.[119] However, two jurors said as late as 2005 that they believed the defense's case. They also said that the prosecution had not proved that Till had died, nor that it was his body that was removed from the river.[118] In November 1955, a grand jury declined to indict Bryant and Milam for kidnapping, despite their own admissions of having taken Till. Mose Wright and a young man named Willie Reed, who testified to seeing Milam enter the shed from which screams and blows were heard, both testified in front of the grand jury.[120] After the trial, T. R. M. Howard paid the costs of relocating to Chicago for Wright, Reed, and another black witness who testified against Milam and Bryant, in order to protect the three witnesses from reprisals for having testified.[115] Reed, who later changed his name to Willie Louis to avoid being found, continued to live in the Chicago area until his death on July 18, 2013. He avoided publicity and even kept his history secret from his wife until she was told by a relative. Reed began to speak publicly about the case in the PBS documentary The Murder of Emmett Till, which was broadcast in 2003.[121] Media discourseNewspapers in major international cities as well as religious and socialist publications reported outrage about the verdict and strong criticism of American society, while Southern newspapers, particularly in Mississippi, wrote that the court system had done its job.[122] Till's story continued to make the news for weeks following the trial, sparking debate in newspapers, among the NAACP and various high-profile segregationists about justice for blacks and the propriety of Jim Crow society.[citation needed] In October 1955, the Jackson Daily News reported facts about Till's father that had been suppressed by the U.S. military. While serving in Italy, Louis Till was court-martialed for the rape of two women and the killing of a third. He was found guilty and executed by hanging by the Army near Pisa in July 1945. Mamie Till-Bradley and her family knew none of this, having been told only that Louis had been killed for "willful misconduct." Mississippi senators James Eastland and John C. Stennis probed Army records and revealed Louis Till's crimes. Although Emmett Till's murder trial was over, news about his father was carried on the front pages of Mississippi newspapers for weeks in October and November 1955. This renewed debate about Emmett Till's actions and Carolyn Bryant's integrity. Stephen Whitfield writes that the lack of attention paid to identifying or finding Till is "strange" compared to the amount of published discourse about his father.[123] According to historians Davis Houck and Matthew Grindy, "Louis Till became a most important rhetorical pawn in the high-stakes game of north versus south, black versus white, NAACP versus White Citizens' Councils."[13] In 2016, reviewing the facts of the rapes and murder for which Louis Till had been executed, John Edgar Wideman posited that, given the timing of the publicity about Emmett's father, although the defendants had already confessed to taking Emmett from his uncle's house, the post-murder trial grand jury refused to even indict them for kidnapping.[124][125] Wideman also suggested that the conviction and punishment of Louis Till may have been racially motivated, referring to his trial as a "kangaroo court-martial."[126][127][125][128]

—William Faulkner, "On Fear", 1956[129]

Protected against double jeopardy, Bryant and Milam struck a deal with Look magazine in 1956 to tell their story to journalist William Bradford Huie for between $3,600 and $4,000. The interview took place in the law firm of the attorneys who had defended Bryant and Milam. Huie did not ask the questions; Bryant and Milam's own attorneys did. Neither attorney had heard their clients' accounts of the murder before. According to Huie, the older Milam was more articulate and sure of himself than the younger Bryant. Milam admitted to shooting Till and neither of them believed they were guilty or that they had done anything wrong.[130]  Reaction to Huie's interview with Bryant and Milam was explosive. Their brazen admission that they had murdered Till caused prominent civil rights leaders to push the federal government harder to investigate the case. Till's murder contributed to congressional passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1957: it authorized the U.S. Department of Justice to intervene in local law enforcement issues when individual civil rights were being compromised.[47] Huie's interview, in which Milam and Bryant said they had acted alone, overshadowed inconsistencies in earlier versions of the stories. As a consequence, details about others who had possibly been involved in Till's abduction and murder, or the subsequent cover-up, were forgotten, according to historians David and Linda Beito.[131][o] Later eventsTill's murder increased fears in the local black community that they would be subjected to violence and the law would not protect them. According to Deloris Melton Gresham, whose father was killed a few months after Till, "At that time, they used to say that 'it's open season on n*****s.' Kill'em and get away with it."[132] After Bryant and Milam admitted to Huie that they had killed Till, the support base of the two men eroded in Mississippi.[133] Many of their former friends and supporters, including those who had contributed to their defense funds, cut them off. Blacks boycotted their shops, which went bankrupt and closed, and banks refused to grant them loans to plant crops.[47] After struggling to secure a loan and find someone who would rent to him, Milam managed to secure 217 acres (88 ha) and a $4,000 loan to plant cotton, but blacks refused to work for him. Milam was forced to pay whites higher wages.[134] Eventually, Milam and Bryant relocated to Texas, but their infamy followed them; they continued to generate animosity from locals. In 1961, while in Texas, when Bryant recognized the license plate of a Tallahatchie County resident, he called out a greeting and identified himself. The resident, upon hearing the name, drove away without speaking to Bryant.[135] After several years, they returned to Mississippi.[134] Milam found work as a heavy equipment operator, but ill health forced him into retirement. Over the years, Milam was tried for offenses including assault and battery, writing bad checks, and using a stolen credit card. He died of spinal cancer on December 31, 1980, at the age of 61.[134] Bryant worked as a welder while in Texas, until increasing blindness forced him to give up this employment. At some point, he and Carolyn divorced; he remarried in 1980. Bryant opened a store in Ruleville, Mississippi. He was convicted in 1984 and 1988 of food stamp fraud. In a 1985 interview, Bryant denied killing Till despite having admitted to it in 1956, but said: "if Emmett Till hadn't got out of line, it probably wouldn't have happened to him." Fearing economic boycotts and retaliation, Bryant lived a private life and refused to be photographed or reveal the exact location of his store, explaining: "this new generation is different and I don't want to worry about a bullet some dark night".[136] He died of cancer on September 1, 1994, at the age of 63.[137] Mamie Till married Gene Mobley, became a teacher, and changed her surname to Till-Mobley. She continued to educate people about her son's murder. In 1992, Till-Mobley had the opportunity to listen while Bryant was interviewed about his involvement in Till's murder. With Bryant unaware that Till-Mobley was listening, he asserted that Till had ruined his life, expressed no remorse, and said: "Emmett Till is dead. I don't know why he can't just stay dead."[138] In 1996, documentary filmmaker Keith Beauchamp, who was greatly moved by Till's open-casket photograph,[99] started background research for a feature film he planned to make about Till's murder. He asserted that as many as 14 people may have been involved, including Carolyn Bryant Donham (who by this point had remarried). Mose Wright heard someone with "a lighter voice" affirm that Till was the one in his front yard immediately before Bryant and Milam drove away with the boy. Beauchamp spent the next nine years producing The Untold Story of Emmett Louis Till, released in 2003. That same year, PBS aired an installment of American Experience titled The Murder of Emmett Till. In 2005, CBS journalist Ed Bradley aired a 60 Minutes report investigating the Till murder, part of which showed him tracking down Carolyn Bryant at her home in Greenville, Mississippi.[139] A 1991 book written by Stephen J. Whitfield, another by Christopher Metress in 2002, and Mamie Till-Mobley's memoirs the next year all posed questions as to who was involved in the murder and cover-up. Federal authorities in the 21st century worked to resolve the questions about the identity of the body pulled from the Tallahatchie River.[140] In 2004, the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) announced that it was reopening the case to determine whether anyone other than Milam and Bryant was involved.[141] David T. Beito, a professor at the University of Alabama, states that Till's murder "has this mythic quality like the Kennedy assassination".[110] The DOJ had undertaken to investigate numerous cold cases dating to the civil rights movement, in the hope of finding new evidence in other murders as well. Till's body was exhumed, and the Cook County coroner conducted an autopsy in 2005. Using DNA from Till's relatives, dental comparisons to images taken of Till, and anthropological analysis, the exhumed body was positively identified as that of Till. It had extensive cranial damage, a broken left femur, and two broken wrists. Metallic fragments found in the skull were consistent with bullets being fired from a .45 caliber gun.[142] In February 2007, a Leflore County grand jury, composed primarily of black jurors and empaneled by Joyce Chiles, a black prosecutor, found no credible basis for Beauchamp's claim that 14 people took part in Till's abduction and murder. Beauchamp was angry with the finding. David Beito and Juan Williams, who worked on the reading materials for the Eyes on the Prize documentary, were critical of Beauchamp for trying to revise history and taking attention away from other cold cases.[143] The grand jury failed to find sufficient cause for charges against Carolyn Bryant Donham. Neither the FBI nor the grand jury found any credible evidence that Henry Lee Loggins, identified by Beauchamp as a suspect who could be charged, had any role in the crime. Other than Loggins, Beauchamp refused to name any of the people he alleged were involved.[110] Historical markers

—Patrick Weems, executive director of the Emmett Till Memorial Commission, speaking in October 2019 at the unveiling of a bulletproof historical marker (the previous three markers at the site having been shot up) near the Tallahatchie River.[144]

The first highway marker remembering Emmett Till, erected in 2006, was defaced with "KKK", and then completely covered with black paint.[145] In 2007, eight markers were erected at sites associated with Till's lynching. The marker at the "River Spot" where Till's body was found was torn down in 2008, presumably thrown in the river. A replacement sign received more than 100 bullet holes over the next few years.[146] Another replacement was installed in June 2018, and in July it was vandalized by bullets. Three University of Mississippi students were suspended from their fraternity after posing in front of the bullet-riddled marker, with guns, and uploading the photo to Instagram.[147] As stated by reporter Jerry Mitchell, "It is not clear whether the fraternity students shot the sign or are simply posing before it."[147] In 2019, a fourth sign was erected. It is made of steel, weighs 500 pounds (230 kg), is over 1 inch (2.5 cm) thick, and is said by its manufacturer to be indestructible.[148] Claim that Carolyn Bryant recanted her testimonyIn 2017, historian and author Timothy Tyson released details of a 2008 interview with Carolyn Bryant, during which, he alleged, she had disclosed that Bryant had fabricated parts of her testimony at the trial.[114][50][3] According to Tyson's account of the interview, Bryant retracted her testimony that Till had grabbed her around her waist and uttered obscenities, saying "that part's not true".[149][150] The jury did not hear Bryant's testimony at the trial as the judge had ruled it inadmissible, but the court spectators heard. The defense wanted Bryant's testimony as evidence for a possible appeal in case of a conviction.[114][151] In the 2007 interview, the 72-year-old Bryant said she could not remember the rest of the events that occurred between her and Till in the grocery store.[114] Tyson also reported her as saying: "nothing that boy did could ever justify what happened to him."[150] Tyson said that Roy Bryant had been abusive toward Carolyn, and "it was clear she was frightened of her husband." Tyson believed Bryant embellished her testimony under coercive circumstances. Bryant described Milam as "domineering and brutal and not a kind man".[150] An editorial in The New York Times said, regarding Bryant's admission that portions of her testimony were false: "This admission is a reminder of how black lives were sacrificed to white lies in places like Mississippi. It also raises anew the question of why no one was brought to justice in the most notorious racially motivated murder of the 20th century, despite an extensive investigation by the F.B.I."[152] The New York Times quoted Wheeler Parker, a cousin of Till's, who said: "I was hoping that one day she [Bryant] would admit it, so it matters to me that she did, and it gives me some satisfaction. It's important to people understanding how the word of a white person against a black person was law, and a lot of black people lost their lives because of it. It really speaks to history, it shows what black people went through in those days."[3][153] However, the 'recanting' claim made by Tyson was not on his tape-recording of the interview. "It is true that that part is not on tape because I was setting up the tape recorder" Tyson said. The support Tyson provided to back up his claim, was a handwritten note that he said had been made at the time.[54] In a report to Congress in March 2018, the U.S. Department of Justice stated that it was reopening the investigation into Till's death due to new information.[154][155] In December 2021, the DOJ announced that it had closed its investigation in the case.[156][157] Discovery of unserved arrest warrantIn June 2022, an unserved arrest warrant for Carolyn Bryant (now known as Carolyn Bryant Donham), dated August 29, 1955, and signed by the Leflore County Clerk, was discovered in a courthouse basement by members of the Emmett Till Legacy Foundation. Following the discovery, Till's family called for Donham's arrest.[158][159][160] However, the district attorney declined to charge Donham, and said that there was no new evidence to reopen the case.[161][162][163] In August 2022, a grand jury concluded there was insufficient evidence to indict Donham.[164] In December 2022, Bowling Green, Kentucky, canceled its annual Christmas parade scheduled for December 3, 2022, due to threats of violence against groups who planned to protest outside Donham's home, an apartment at Shive Lane, Bowling Green. The protests took place peacefully.[165] Carolyn Bryant Donham memoirIn 2022, I Am More Than a Wolf Whistle, the 99-page memoir of Carolyn Bryant Donham, was copied and given to NewsOne by an anonymous source. The text had been given to the University of North Carolina to privately hold until 2036.[166] The memoir had been prepared by Donham's daughter-in-law Marsha Bryant, who had shared the material with Timothy Tyson, with the understanding that Tyson would edit the memoir. However, Tyson said there had been no such agreement, and placed the memoir at the Southern Historical Collection at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill library archives, with access restricted for 20 years or until Donham's death.[54] Donham died on April 25, 2023, at the age of 88.[167][168] Influence on civil rightsTill's case became emblematic of the injustices suffered by blacks in the South.[169] Myrlie Evers, the widow of Medgar Evers, said years later that the case "struck a spark of indignation that ... touched off a world-wide clamor and cast the glare of a world spotlight on Mississippi's racism."[170] Mamie Till toured the country in one of the NAACP's most successful fundraising campaigns ever.[171] Journalist Louis Lomax acknowledges Till's death to be the start of what he terms the "Negro revolt", and scholar Clenora Hudson-Weems characterizes Till as a "sacrificial lamb" for civil rights. NAACP operative Amzie Moore considers Till the start of the Civil Rights Movement, at the very least in Mississippi.[172] The 1987 Emmy award-winning documentary series Eyes on the Prize, begins with the murder of Emmett Till. Accompanying written materials for the series, Eyes on the Prize and Voices of Freedom (for the second time period), exhaustively explore the major figures and events of the Civil Rights Movement. Stephen Whitaker states that, as a result of the attention Till's death and the trial received,

—Rosa Parks, on her refusal to move to the back of the bus, launching the Montgomery bus boycott.[170]

In Montgomery a few months after the murder, Rosa Parks attended a rally for Till, led by Martin Luther King Jr.[173] Soon after, she refused to give up her seat on a segregated bus to a white passenger. The incident sparked a year-long well-organized grassroots boycott of the public bus system. The boycott was designed to force the city to change its segregation policies. Parks later said when she did not get up and move to the rear of the bus, "I thought of Emmett Till and I just couldn't go back."[174] According to author Clayborne Carson, Till's death and the widespread coverage of the students integrating Little Rock Central High School in 1957 were especially profound for younger blacks: "It was out of this festering discontent and an awareness of earlier isolated protests that the sit-ins of the 1960s were born."[175]After seeing pictures of Till's mutilated body, in Louisville, Kentucky, young Cassius Clay (later famed boxer Muhammad Ali) and a friend took out their frustration by vandalizing a local railyard, causing a locomotive engine to derail.[176][177] In 1963, Sunflower County resident and sharecropper Fannie Lou Hamer was jailed and beaten for attempting to register to vote. The next year, she led a massive voter registration drive in the Delta region, and volunteers worked on Freedom Summer throughout the state. Before 1954, 265 black people were registered to vote in three Delta counties, where they were a majority of the population. At this time, blacks made up 41% of the total state population. The summer Emmett Till was killed, the number of registered voters in those three counties dropped to 90. By the end of 1955, 14 Mississippi counties had no registered black voters.[178] The Mississippi Freedom Summer of 1964 registered 63,000 black voters in a simplified process administered by the project; they formed their own political party because they were closed out of the Democratic Regulars in Mississippi.[179] Legacy and honors

Casket

—Lonnie Bunch III, director of the Smithsonian's National Museum of African American History and Culture[206]

During a renewed investigation of the crime in 2005, the Department of Justice exhumed Till's remains to conduct an autopsy and DNA analysis which confirmed the identification of his body. As required by state reburial law, Till was reinterred in a new casket later that year.[207] In 2009, his original glass-topped casket was found, rusting in a dilapidated storage shed at the cemetery.[208] The casket was discolored and the interior fabric torn. It bore evidence that animals had been living in it, although its glass top was still intact. The Smithsonian's National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C. acquired the casket a month later.[206] Representation in cultureLangston Hughes dedicated an untitled poem (eventually to be known as "Mississippi—1955") to Till in his October 1, 1955, column in The Chicago Defender. It was reprinted across the country and continued to be republished with various changes from different writers.[209] William Faulkner, a prominent white Mississippi native who often focused on racial issues, wrote two essays on Till: one before the trial in which he pleaded for American unity and one after, a piece titled "On Fear" that was published in Harper's in 1956. In it he questioned why the tenets of segregation were based on irrational reasoning.[129] Till's murder was the focus of a 1957 television episode for the U.S. Steel Hour titled "Noon on Doomsday" written by Rod Serling. He was fascinated by how quickly Mississippi whites supported Bryant and Milam. Although the script was rewritten to avoid mention of Till, and did not say that the murder victim was black, White Citizens' Councils vowed to boycott U.S. Steel. The eventual episode bore little resemblance to the Till case.[210] Writer James Baldwin loosely based his 1964 drama Blues for Mister Charlie on the Till case. He later divulged that Till's murder had been bothering him for several years.[211] Anne Moody mentioned the Till case in her autobiography, Coming of Age in Mississippi, in which she states she first learned to hate during the fall of 1955.[212][213] Audre Lorde's poem "Afterimages" (1981) focuses on the perspective of a black woman thinking of Carolyn Bryant 24 years after the murder and trial.[citation needed] Bebe Moore Campbell's 1992 novel Your Blues Ain't Like Mine centers on the events of Till's death.[citation needed] Toni Morrison mentions Till's death in the novel Song of Solomon (1977) and later wrote the play Dreaming Emmett (1986), which follows Till's life and the aftermath of his death.[214] The play is a feminist look at the roles of men and women in black society, which she was inspired to write while considering "time through the eyes of one person who could come back to life and seek vengeance".[215] Emmylou Harris includes a song called "My Name is Emmett Till" on her 2011 album, Hard Bargain. According to scholar Christopher Metress, Till is often reconfigured in literature as a specter that haunts the white people of Mississippi, causing them to question their involvement in evil, or silence about injustice.[211] The 2021 novel The Trees by Percival Everett uses this theme.[216][217] The 2002 book Mississippi Trials, 1955 is a fictionalized account of Till's death. The 2015 song by Janelle Monáe, "Hell You Talmbout", invokes the names of African-American people—including Emmett Till—who died as a result of encounters with law enforcement or racial violence. In 2016 artist Dana Schutz painted Open Casket, a work based on photographs of Till in his coffin as well as on an account by Till's mother of seeing him after his death.[218] Documentaries

Works inspired by TillThis section includes creative works inspired by Till. For non-fiction books on Till, see Bibliography, below. Songs

On screen

Other

Gallery

See also

Notes

References

Bibliography

Further reading

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Emmett Till.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

![Emmett Till Historic Intrepid Center housed in the old cotton gin of Glendora, Mississippi.[241]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/42/Emmett_Till_Historic_Intrepid_Center.jpg/220px-Emmett_Till_Historic_Intrepid_Center.jpg)

![Clinton Melton was the victim of a racially motivated killing a few months after Till. Despite eyewitness testimony, his killer, a friend of Milam's, was acquitted by an all-white jury at the same courthouse.[132]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/e5/Site_of_killing_of_Clinton_Melton.jpg/159px-Site_of_killing_of_Clinton_Melton.jpg)

![The reconstructed Ben Roy Service Station that stood next to the grocery store where Till encountered Bryant in Money, Mississippi,[242] 2019](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/66/Ben_Roy_Service_Station.jpg/220px-Ben_Roy_Service_Station.jpg)

![Bryant's Grocery (2018). By 2018, the store was described as "not much left" and given owner's demands, no preservation occurred.[243]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/e8/Bryant%27s_Grocery_2018.jpg/220px-Bryant%27s_Grocery_2018.jpg)