|

Mud March (suffragists)

The United Procession of Women, or Mud March as it became known, was a peaceful demonstration in London on 9 February 1907 organised by the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), in which more than three thousand women marched from Hyde Park Corner to the Strand in support of women's suffrage. Women from all classes participated in what was the largest public demonstration supporting women's suffrage seen up to that date. It acquired the name "Mud March" from the day's weather, when incessant heavy rain left the marchers drenched and mud-spattered. The proponents of women's suffrage were divided between those who favoured constitutional methods and those who supported direct action. In 1903 Emmeline Pankhurst formed the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU). Known as the suffragettes, the WSPU held demonstrations, heckled politicians, and from 1905 saw several of its members imprisoned, which gained press attention and increased support from women. To maintain that momentum and to create support for a new suffrage bill in the House of Commons, the NUWSS and other groups organised the Mud March to coincide with the opening of Parliament. The event attracted much public interest and broadly sympathetic press coverage, but when the bill was presented the following month, it was "talked out" without a vote. While the march failed to influence the immediate parliamentary process, it had a considerable impact on public awareness and on the movement's future tactics. Large peaceful public demonstrations, never previously attempted, became standard features of the suffrage campaign; on 21 June 1908 up to half a million people attended Women's Sunday, a WSPU rally in Hyde Park. The marches showed that the fight for women's suffrage had the support of women in every stratum of society, who despite their social differences were able to unite and work together for a common cause. BackgroundEmmeline Pankhurst of the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) In October 1897 Millicent Fawcett was the driving force behind the formation of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), a new umbrella organisation for all the factions and regional societies, and to liaise with sympathetic MPs. Initially, seventeen groups affiliated to the new central body. The organisation became the leading body following a constitutional path to women's suffrage.[1][2][3] In October 1903 Emmeline Pankhurst and her daughter Christabel Pankhurst formed a women-only group in Manchester, the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU). Although the NUWSS sought its objectives through constitutional means, such as petitions to parliament,[4] the WSPU organised open-air meetings and heckled politicians and chose jail over fines when it was prosecuted.[5] From 1906 it began to use the nickname "suffragettes", which differentiated it from the constitutionalist "suffragists".[6][a] At the time of the Mud March, before the suffragette campaign had progressed to damaging property, relations between the WSPU and NUWSS remained cordial.[8] When eleven suffragettes were jailed in October 1906 after a protest in the House of Commons lobby, Fawcett and the NUWSS stood by them. On 27 October 1906, in a letter to The Times, she wrote:

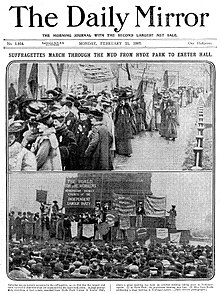

The militant actions of the WSPU raised the profile of the women's suffrage campaign in Britain and the NUWSS wanted to show that they were as committed as the suffragettes to the cause.[10][11] In January 1906 the Liberal Party, led by Henry Campbell-Bannerman, had won an overwhelming general election victory; although before the election many Liberal MPs had promised that the new administration would introduce a women's suffrage bill, once in power, Campbell-Bannerman said that it was "not realistic" to introduce new legislation.[12] A month after the election, the WSPU held a successful London march, attended by 300–400 women.[13] To show there was support for a suffrage bill, the Central Society for Women's Suffrage suggested, in November 1906, holding a mass procession in London to coincide with the opening of Parliament in February.[14][10] The NUWSS called on its members to join the march.[15] MarchOrganisation The task of organising the event, scheduled for Saturday, 9 February 1907, was delegated to Pippa Strachey[16] of the Central Society for Women's Suffrage.[b] Her mother, Lady Jane Strachey, a friend of Fawcett, was a long-standing suffragist, but Pippa Strachey had shown little interest in the issue before a meeting with Emily Davies, who quickly converted her to the cause. She took on the organisation of the London march with no experience of doing anything similar, but carried out the task so effectively that she was given responsibility for the planning of all future large processions of the NUWSS.[16] On 29 January the executive committee of the London Society determined the order of the procession and arranged for advertisements to be placed in the Tribune and The Morning Post.[14] Regional suffrage societies and other organisations were invited to bring delegations to the march. The art historian Lisa Tickner writes that "all sensibilities and political disagreements had to be soothed" to make sure the various groups would take part. The Women's Cooperative Guild would attend only if certain conditions were met, and the British Women's Temperance Association and Women's Liberal Federation (WLF) would not attend if the WSPU was formally invited. The WLF—a "crucial lever on the Liberal government", according to Tickner—objected to the WSPU's criticism of the government.[11][14] At the time of the march, ten of the twenty women who sat on the NUWSS executive committee were connected to the Liberal Party.[19] The march would begin at Hyde Park Corner and progress via Piccadilly to Exeter Hall, a large meeting venue on the Strand.[20] A second open-air meeting was scheduled for Trafalgar Square.[21] Members of the Artists' Suffrage League produced posters and postcards for the march.[22] In all, around forty organisations from all over the country chose to participate.[11] 9 February On the morning of 9 February, large numbers of women converged on the march's starting point, the statue of Achilles near Hyde Park Corner.[23] Between three and four thousand women were assembled, from all ages and strata of society, in appalling weather with incessant rain; "mud, mud, mud" was the dominant feature of the day, wrote Fawcett.[24] The marchers included Lady Frances Balfour, sister-in-law of Arthur Balfour, the former Conservative prime minister; Rosalind Howard, the Countess of Carlisle, of the Women's Liberal Federation; the poet and trade unionist Eva Gore-Booth; and the veteran campaigner Emily Davies.[25] The march's aristocratic representation was matched by numbers of professional women – doctors, schoolmistresses, artists[26] – and large contingents of working women from northern and other provincial cities, marching under banners that proclaimed their varied trades: bank-and-bobbin winders, cigar makers, clay-pipe finishers, power-loom weavers, shirt makers.[27] Although the WSPU was not officially represented, many of its members attended, including Christabel Pankhurst, Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, Annie Kenney, Anne Cobden-Sanderson, Nellie Martel, Edith How-Martyn, Flora Drummond, Charlotte Despard and Gertrude Ansell.[28][29][30] According to the historian Diane Atkinson, "belonging to both organisations, going to each others' events and wearing both badges was quite usual".[28]  By around 2:30 pm the march had formed a line that stretched far down Rotten Row. It set off in the drenching rain with a brass band leading and Lady Frances Balfour, Millicent Fawcett and Lady Jane Strachey at the head of the column.[15] The procession was followed by a phalanx of carriages and motor cars, many of which carried flags bearing the letters "WS", red-and-white banners and bouquets of red and white flowers.[31][32] Around 7,000 red-and-white rosettes had been provided for the marchers by the manufacturing company of Maud Arncliffe-Sennett, an actor and leader among the London Society for Women's Suffrage and the Actresses Franchise League.[33] Despite the weather, thousands thronged the pavements to enjoy the novel spectacle of "respectable women marching in the streets", according to the historian Harold Smith.[11] The Observer's reporter recorded that "there was hardly any of the derisive laughter which had greeted former female demonstrations",[27] although The Morning Post reported "scoffs and jeers of enfranchised males who had posted themselves along the line of the route, and appeared to regard the occasion as suitable for the display of crude and vulgar jests".[34] Katharine Frye, who joined the march at Piccadilly Circus, recorded "not much joking at our expense and no roughness".[35][36] The Daily Mail—which supported women's suffrage—carried an eyewitness account, "How It Felt", by Constance Smedley of the Lyceum Club. Smedley described a divided reaction from the crowd "that shared by the poorer class of men, namely, bitter resentment at the possibility of women getting any civic privilege they had not got; the other that of amusement at the fact of women wanting any serious thing ... badly enough to face the ordeal of a public demonstration".[37]  Approaching Trafalgar Square the march divided: representatives from the northern industrial towns broke off for an open-air meeting at Nelson's Column, which had been arranged by the Northern Franchise Demonstration Committee.[21][38] The main march continued to Exeter Hall for a meeting chaired by the Liberal politician Walter McLaren, whose wife, Eva McLaren, was one of the scheduled speakers.[35] Keir Hardie, leader of the Labour Party, told the meeting, to hissing from several Liberal women on the platform, that if women won the vote, it would be thanks to the "suffragettes' fighting brigade".[28][39] He spoke strongly in favour of the meeting's resolution, which was carried, that women be given the vote on the same basis as men,[40] and demanded a bill in the current parliamentary session.[41] At the Trafalgar Square meeting Eva Gore-Booth referred to the "alienation of the Labour Party through the action of a certain section in the suffrage movement", according to The Observer, and asked the party "not to punish the millions of women workers" because of the actions of a small minority. When Hardie arrived from Exeter Hall, he expressed the hope that "no working man bring discredit on the class to which he belonged by denying to women those political rights which their fathers had won for them".[21] AftermathPress reaction The press coverage gave the movement "more publicity in a week", according to one commentator, "than it had enjoyed in the previous fifty years".[20] Tickner writes that the reporting was "inflected by the sympathy or otherwise of particular newspapers for the suffrage cause".[38] The Daily Mirror, which was neutral on the issue of women's suffrage, offered a large photospread[42] and praised the crowd's diversity.[43] The Tribune also commented on the mix of social classes represented in the marchers.[26] The Times, an opponent of women's suffrage,[42] thought the event "remarkable as much for its representative character as for its size" and described the scenes and speeches in detail over 20 column inches.[44] The protesters had had to "run the gauntlet of much inconsiderate comment", according to the Daily Chronicle, a publication supportive of women's suffrage.[45] The pictorial journal The Sphere provided a montage of photographs under the headline "The Attack on Man's Supremacy".[30] The Graphic, a pro-suffrage paper, published a series of illustrations sympathetic to the event except for one that showed a man holding aloft a pair of scissors "suggesting that demonstrating women should have their tongues cut out", according to Katherine Kelly in a study of how the suffrage movement was portrayed in the British press.[42] Some newspapers, including The Times and the Daily Mail, carried pieces written by the marchers.[42] In its leading article, The Observer warned that "the vital civic duty and natural function of women ... is the healthy propagation of race" and that the aim of the movement was "nothing less than complete sex emancipation".[c] It was concerned that women were not ready for the vote. The movement should educate its own sex, it said, rather than "seeking to confound men". The newspaper nevertheless welcomed that there had been "no attempts to bash policemen's helmets, to tear down the railings of the Park, to utter piercing war cries ..."[46] Likewise, The Daily News compared the event favourably to the actions of suffragettes: "Such a demonstration is far more likely to prove the reality of the demand for a vote than the practice of breaking up meetings held by Liberal Associations".[47] The Manchester Guardian agreed: "For those ... who, like ourselves, wish to see this movement – a great movement, as will one day be recognised – carried through in such a way as to win respect even where it cannot command agreement Saturday's demonstration was of good omen."[48] Dickinson Bill Four days after the march, the NUWSS executive met with the Parliamentary Committee for Women's Suffrage (founded 1893) to discuss a private member's bill.[15][49] On the same day, the suffragettes held their first "Women's Parliament" at Caxton Hall, after which four hundred women marched toward the Commons to protest against the omission from the King's Speech, the day before, of a women's suffrage bill; over sixty were arrested, and fifty-three chose prison over a fine.[50][51] On 26 February 1907 the Liberal MP for St Pancras North, Willoughby Dickinson, published the text of a bill proposing that women should have the vote subject to the same property qualification that applied to men. That would, it was estimated, enfranchise between one and two million women.[52] (On the day that the bill was published, the Cambridge Union passed by a small majority a motion "that this House would view with regret the extension of the franchise to women".)[53] Although the bill received strong backing from the suffragist movement, it was viewed more equivocally in the House of Commons, some of whose members regarded it as giving more votes to the propertied classes but doing nothing for working women.[54] On 8 March Dickinson introduced his Women's Enfranchisement Bill to the House of Commons for its second reading, with a plea that members should not be swayed by their distaste for militant actions;[55] the House of Commons "Ladies Gallery" was kept closed during the debate for fear of protests by the WSPU.[56] The debate was inconclusive and the bill was "talked out" without a vote.[57][58] The NUWSS had worked hard for the bill and found the response insulting.[57] LegacyThe Mud March was the largest-ever public demonstration until then in support of woman's suffrage.[15] Although it brought little by way of immediate progress on the parliamentary front, its significance in the general suffrage campaign was considerable. By embracing activism, the constitutionalists' tactics become closer to those of the WSPU, at least in relation to the latter's non-violent activities.[39] In her 1988 study of the suffrage campaign, Tickner observes that "modest and uncertain as it was by subsequent standards, [the march] established the precedent of large-scale processions, carefully ordered and publicised, accompanied by banners, bands and the colours of the participant societies".[59] The feminist politician Ray Strachey wrote:

The march marked a change in perception of the NUWSS from what The Manchester Guardian described as "regional debating society" into the sphere of "practical politics".[61] According to Jane Chapman, in her study Gender, Citizenship and Newspapers, the Mud March "established a precedent for advance press publicity".[62] The failure of Dickinson's bill brought about a change in the NUWSS's strategy; it began to intervene directly in by-elections, on behalf of the candidate of any party who would publicly support women's suffrage. In 1907 the NUWSS supported the Conservatives in Hexham and Labour in Jarrow; where no suitable candidate was available they used the by-election to propagandise. This tactic met with sufficient success for the NUWSS to resolve that it would fight in all future by-elections,[63] and between 1907 and 1909 they had been involved in 31 by-elections.[23] From 1907 to the start of the First World War, the NUWSS and suffragettes held several peaceful demonstrations. On 13 June 1908 over ten thousand women took part in a London march organised by the NUWSS,[23] and on 21 June the suffragettes organised Women's Sunday in Hyde Park, which was attended by up to half a million.[64] During the NUWSS's Great Pilgrimage of April 1913, women marched from all over the country to London for a mass rally in Hyde Park, which fifty thousand attended.[65] Their struggles were rewarded after the First World War when women were partly enfranchised by the Representation of the People Act 1918, which granted the vote to women over 30 who owned property with a rateable value above £5, or whose husbands did; women then constituted 39.6 per cent of the electorate. The restriction that only those eligible to vote in the local elections by virtue of their property status meant that approximately 22 per cent of women aged 30 and above were not enfranchised.[66] The Act also extended the franchise for men aged 21 or over.[67] Full enfranchisement of all women over 21 came ten years later, when the Representation of the People (Equal Franchise) Act of 1928 was passed by a Conservative government under Stanley Baldwin.[68] The Mud March is featured in window No. 4 of the stained-glass Dearsley Windows in St Stephen's Hall in the Palace of Westminster. The window includes panels depicting, among other things, the formation of the NUWSS, WSPU and Women's Freedom League, the NUWSS's Great Pilgrimage, the force-feeding of suffragettes, the Cat and Mouse Act and the death in 1913 of Emily Davison. The window was installed in 2002 as a memorial to the long and ultimately successful campaign for women's suffrage.[69][70] See also

Notes and referencesNotes

References

SourcesBooks

Journals

Newspapers

Websites

Further readingWikimedia Commons has media related to Mud March (suffragists).

|