|

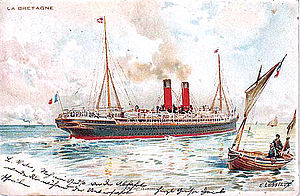

SS La Bretagne

SS La Bretagne was an ocean liner that sailed for the Compagnie Générale Transatlantique (CGT) from her launch in 1886 to 1912, sailing primarily in transatlantic service on the North Atlantic. Sold to Compagnie de Navigation Sud-Atlantique in 1912, she sailed for that company under her original name and, later, as SS Alesia on France–South America routes. The liner was sold for scrapping in the Netherlands in December 1923, but was lost while being towed. Design and constructionIn March 1885, Compagnie Générale Transatlantique (CGT), announced the building of four new steamers for the Le Havre–New York route at the company's Penhoët ship yard. The similarly sized steamers, La Champagne, La Bourgogne, La Bretagne, and La Gascogne, were built under a French government subsidy law that provided that the ships could be taken over in a time of war. CGT also announced that noted French designer Jules Allard would decorate the four ships.[1]  La Bretagne was launched 9 September 1885 by CGT in Saint-Nazaire.[2] Built for France to New York service, she had a 7,112 gross register tons (GRT) and measured 150.99 metres (495 ft 4 in) long between perpendiculars and 15.78 metres (51 ft 9 in) wide. Equipped with twin triple-expansion steam engines driving a single screw propeller that drove her at 17 knots (31 km/h), she was outfitted with two funnels and four masts carrying a barquentine rig. La Bretagne was initially equipped with accommodations for 390 first-class, 65 second-class, and 600 third-class passengers.[2] Her hull was made of steel from the foundries at Terre-Noire and featured eleven bulkheads which created twelve watertight compartments; her deck was planked with Canadian elm and teak. The ship cost $1,700,000 (about $58 million today)[3], exclusive of decorations which were provided for $75,000 by CGT employees.[4] CGT careerLa Bretagne began her maiden voyage from Le Havre to New York on 14 August 1886,[2] and arrived on 22 August after a storm-tossed voyage carrying 281 passengers.[4] In April 1891, Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky sailed to New York on the liner, for his one trip to the United States.[5] In June 1891, a westbound passage was marred when a drunken man flung his five-year-old son overboard in mid ocean. The man was seized and straitjacketed while a boat was launched in an unsuccessful attempt to save the boy.[6] In the last quarter of 1892, La Bretagne seemed to be jinxed. In September, a cholera outbreak, traced to a United States immigrant brought aboard the Hamburg-Amerika steamer Moravia, caused all steerage traffic to be suspended and CGT's New York traffic to depart from Cherbourg for the next two months.[7] La Bretagne, arriving in New York in mid-September, was caught in the middle of the outbreak and was detained at the New York Quarantine Station (though the liner had no cases reported on board). Among the passengers aboard was John D. Washburn, the United States Minister to Switzerland, who was leaving his diplomatic post.[8] On her next voyage, a purser's error resulted in the ship being detained for an "uncomfortable long time" off Liberty Island in early December while the error was sorted out.[9][10] Departing from her pier at the foot of Morgan Street in New York on 11 December, a pilot error resulted in La Bretagne plowing 50 feet (15 m) through a pier at the foot of Franklin Street.[9] The New York agent for CGT estimated that it would take two weeks to repair the eleven plates crushed by the collision.[11]  The success of upgraded engines on the liner La Normandie in 1894 prompted CGT to make similar changes on several older liners, including La Bretagne. In 1895, her triple-expansion engines were upgraded to quadruple-expansion engines, and her four barquentine-rigged masts were removed and replaced with two pole masts. At the same time, her third-class passenger capacity was nearly tripled, going from 600 to 1,500 passengers.[7] In April 1898, The New York Times reported on a rescue at sea accomplished by La Bretagne's crew that had happened late the previous month. Encountering the dismasted British bark Bothnia, the crew of La Bretagne effected rescue of the stricken ship's master and ten surviving crewmen. The crew then used carrier pigeons to announce the rescue. The carrier pigeons were being carried aboard La Bretagne as a trial program under the watch of a French Army officer, after the CGT liner La Champagne broke her propeller shaft and was adrift for five days in February without any way of communicating her predicament.[12] On 18 May 1899, a fire was discovered in the cargo hold of the outbound North German Lloyd liner Barbarossa, when she had just sailed through the Narrows. Barbarossa's crew—in a panic, according to a Chicago Daily Tribune news story—turned the big liner around and hastily headed back to her pier, ramming the docked La Bretagne in her starboard quarter in the process. The damage to La Bretagne's hull was significant: a hole 25-foot (7.6 m) long, 10 feet (3.0 m) below the waterline that left her in danger of sinking at her pier.[13] By making the ship list to port, La Bretagne's crew were able to get the hole above the waterline and prevent further damage. Estimates in The New York Times two days later put La Bretagne's repair time at ten days. In the meantime, her passengers were able to choose to travel on the Cunard liner RMS Carmania or the CGT liner La Touraine to complete their travel.[14] On 27 May 1909, La Bretagne was tangentially involved in another North German Lloyd liner mishap. Princess Alice, departing for Bremen from New York in a fog, steered clear of La Bretagne and instead ran hard aground near the seawall of Fort Wadsworth.[15] La Bretagne's career was not marked entirely by misfortune. On her August 1902 crossing, a group of about 30 first-cabin passengers formed a vegetarian society, which they called "La Société des Legumineux", that gave the steward fits because they ignored the chef's signature meat dishes of roast beef and Philadelphia chicken. The same voyage carried eight Franciscan nuns—reportedly the last of the expelled order to leave France—on their way to Canada.[16] In September 1905, The New York Times heralded the arrival on La Bretagne of 30 dressmakers and milliners with the latest fall fashions from Paris. Over 200 trunks of women's clothing arrived on the liner, and were inspected by married customs inspectors because, according to the head of the inspectors, "a married man is the only person in the world would know what all that stuff was".[17] Later careerIn 1912, the newly reorganized Compagnie de Navigation Sud-Atlantique purchased a number of second-hand ships—including La Bretagne—for its relaunch of South American service from France.[18] La Bretagne sailed on the South American service through 1923, the last four years under the name of Alesia. In December 1923, Alesia was sold to a Dutch firm for scrapping. While on her way to the shipbreaker, Alesia's tow line parted and the ship ran aground on the island of Texel, becoming a total loss.[2] Notes

References

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Portal di Ensiklopedia Dunia