|

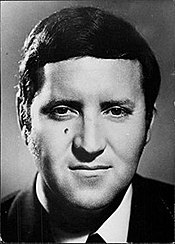

Rowan Cronjé

Rowan Cronjé (22 September 1937 – 8 March 2014) was a Rhodesian politician who served in the cabinet under prime ministers Ian Smith and Abel Muzorewa, and was later a Zimbabwean MP. He emigrated to South Africa in 1985 and served in the government of Bophuthatswana. From 1966 to 1979, nearly the entirety of Rhodesia's independent history, he served as Minister of Health and Minister of Labour and Social Welfare. From 1977 to 1979, he held the newly created office of Minister of Manpower and Social Affairs, and from 1978, was the joint Minister of Education. He was a Member of Parliament from 1970 to 1985, serving in the parliaments of both Rhodesia and Zimbabwe. He was briefly Deputy Minister of Lands, Natural Resources, and Rural Development of Zimbabwe Rhodesia in 1979. In the 1980s, Cronjé relocated to South Africa, serving as Minister of Defense, Minister of Foreign Affairs, and Minister of Aviation in Bophuthatswana in the early 1990s. Early lifeCronjé was born in the Union of South Africa to parents of Afrikaner descent,[1][2] before emigrating to Southern Rhodesia, which was then governed as a British colony. Political careerRhodesiaIn 1966, less than a year after Rhodesia declared independence, Cronjé was appointed Minister of Health and Minister of Labour and Social Welfare, succeeding Ian McLean in both offices.[3][4][5][6][7] He served in these positions until Rhodesia was dissolved and replaced by Zimbabwe in 1979. As labour minister, he oversaw a period in which Rhodesia was experiencing a shortage of workers on its farms. In 1975, he cited 36,000 vacancies for farm jobs, saying, "There is no unemployment in Rhodesia. The fact is we have a labor shortage."[8][9] He also dismissed sanctions or the Rhodesian Bush War as a threat to the Rhodesian economy, insisting as late as 1978 that population growth was the greater problem.[10][11] In 1970, Cronjé ran for the Rhodesian Parliament for the Charter constituency. Running unopposed, he was elected with 1,715 votes. He ran for reelection in 1974 against Neil Diarmid Campbell Housman Herbert Wilson, winning with 1,147 votes, or 92%. He ran for a third term in 1977 against Independent candidate Leonard George Idensohn, winning with 1,023 votes, or 90%. During his time in Parliament, Cronjé was leader of the moderate faction of the Rhodesian Front party.[12] In 1977, Cronjé was appointed minister of the newly created Ministry of Manpower, Industrial Relations, and Social Affairs of Rhodesia.[11][13] The next year, he succeeded Denis Walker as the third Minister of Education of Rhodesia.[14] He served in both positions until Rhodesia dissolved in 1979. In 1978, Gibson Magarombe was appointed to serve with Cronjé as co-Minister of Health and co-Minister of Education.[15] As Minister of Manpower and Social Affairs, he oversaw the elections process as Rhodesia transitioned from white minority rule to multiracial democracy.[16][17] In February 1978, Cronjé was involved in the reaching of an agreement between the Rhodesian government and black leaders on the future of the Rhodesian military.[18][19] In regard to the rebels fighting the government in the Rhodesian Bush War, the leaders agreed that amnesty would be declared and that guerrillas would be offered retraining for entry into the existing army.[18][19] Cronjé said regarding the Rhodesian Bush War, "Black and white will continue fighting until we have won this war." He went on to criticize foreign nations' involvement in the Rhodesian peace and transition efforts, challenging Britain and the United States, and criticizing the "Marxist masters", referring to the Soviet Union and China.[18][19] Zimbabwe Rhodesia and ZimbabweWhen Zimbabwe Rhodesia, an unrecognized successor state to Rhodesia, was established on 1 June 1979, Cronjé was named by Prime Minister Abel Muzorewa to be Deputy Minister of Lands, Natural Resources, and Rural Development.[12] He held that office until Zimbabwe Rhodesia's disestablishment on 12 December 1979.[citation needed] In Zimbabwe Rhodesia and Zimbabwe, 20 of the 100 seats in the House of Assembly in Parliament were reserved for whites, a system that remained until 1987. Cronjé ran for election to one of the seats in 1979, winning election as the unopposed as the Rhodesian Front candidate for the Central constituency. He was reelected in 1980 after running yet again as the unopposed RF candidate,[20] and he served as a Member of Parliament until 1985, when he chose not to run for reelection and emigrated to South Africa shortly after.[citation needed] BophuthatswanaIn 1985, Cronjé left Zimbabwe and emigrated to South Africa, where he became involved in the Afrikaner volkstaat movement, which proposed a separate state with self-determination for the Afrikaner population in South Africa.[1] He relocated to Bophuthatswana, a bantustan which the South African government made independent in 1977 and which was led by President Lucas Mangope. During the transition away from apartheid in South in the early 1990s, the Mangope administration in Bophuthatswana allied itself with Afrikaner nationalists, as they both shared the common goal of a future South Africa of various independent states divided by ethnicity.[1][21] He was also, during the 1980s, a personal advisor to the Ciskei government.[1][22] In 1986, President Mangope appointed Cronjé Minister of Defence,[1][2][21][23][24][25][26][27] Minister of Aviation,[1][28] and Minister of Foreign Affairs[1][7][21][29] (or Minister of State) of Bophuthatswana. He served in those three positions until Bophuthatswana's dissolution in 1994. As a member of the Bophuthatswana cabinet, and in his capacity as defense minister, Cronjé was at the forefront of the bantustan's effort to remain independent of the post-apartheid South Africa, serving as chief negotiator with South African officials.[1][23] He also served as chairman of the Freedom Alliance, a group that brought together tribal leaders, bantustan leaders, and conservative white groups who each strove for self-determination at the beginning of the post-apartheid era.[23][30][31][32] Cronjé said in 1993 about the self-government of Bophuthatswana, "We've got kids who are 16 years old who never knew apartheid. It has restored the self-dignity of blacks here."[1][23] Defending the large number of white cabinet members in Bophuthatswana, he said, "[President Mangope] has realized from the first day, to run the complicated business of a government is not yet within the grasp of his people."[1] As the South African government under President F. W. de Klerk grew closer to reaching an agreement with the African National Congress on the future government of South Africa, so was more pressure placed on Bophuthatswana, from both sides, to agree to give up its quasi-independence and reenter South Africa. Cronjé worked to defuse tensions and avoid confrontation with South Africa, hoping to maintain Bophuthatswana's independence into the future.[23] He said in 1992, "We have experienced the fruits of independence. To give that up, there must be very good reasons."[30] He argued that the homeland would be able to withstand an economic blockade by South Africa, saying in 1993, "We'll have to tighten our belts"[2] and "reduce our budget."[21] He also made it clear that if South Africa tried to use force on Bophuthatswana to rejoin, the country would fight back and would have allies to help defend it, saying, "It would be the beginning of a civil war in South Africa."[2] Ultimately, by December 1993, Bophuthatswana gave up its ambitions for independence and rejoined the negotiations with the South African government and the ANC.[32] By 1994, Bophuthatswana was merged into the new South Africa, and Cronjé's cabinet positions went out of existence. DeathOn 11 March 2014, Cronjé died in his sleep at his home in Pretoria, at the age of 76. His funeral was held on 15 March of that year.[33] Personal lifeCronjé was an ordained minister of the Dutch Reformed Church in Rhodesia.[34] His brother-in-law was South African Conservative Member of Parliament Tom Langley.[28] Electoral history

References

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Portal di Ensiklopedia Dunia