|

Rosalia (festival)

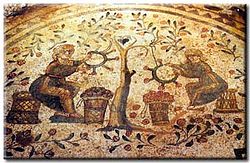

In the Roman Empire, Rosalia or Rosaria was a festival of roses celebrated on various dates, primarily in May, but scattered through mid-July. The observance is sometimes called a rosatio ("rose-adornment") or the dies rosationis, "day of rose-adornment," and could be celebrated also with violets (violatio, an adorning with violets, also dies violae or dies violationis, "day of the violet[-adornment]").[1] As a commemoration of the dead, the rosatio developed from the custom of placing flowers at burial sites. It was among the extensive private religious practices by means of which the Romans cared for their dead, reflecting the value placed on tradition (mos maiorum, "the way of the ancestors"), family lineage, and memorials ranging from simple inscriptions to grand public works. Several dates on the Roman calendar were set aside as public holidays or memorial days devoted to the dead.[2] As a religious expression, a rosatio might also be offered to the cult statue of a deity or to other revered objects. In May, the Roman army celebrated the Rosaliae signorum, rose festivals at which they adorned the military standards with garlands. The rose festivals of private associations and clubs are documented by at least forty-one inscriptions in Latin and sixteen in Greek, where the observance is often called a rhodismos.[3] Flowers were traditional symbols of rejuvenation, rebirth, and memory, with the red and purple of roses and violets felt to evoke the color of blood as a form of propitiation.[4] Their blooming period framed the season of spring, with roses the last of the flowers to bloom and violets the earliest.[5] As part of both festive and funerary banquets, roses adorned "a strange repast ... of life and death together, considered as two aspects of the same endless, unknown process."[6] In some areas of the Empire, the Rosalia was assimilated to floral elements of spring festivals for Dionysus, Adonis and others, but rose-adornment as a practice was not strictly tied to the cultivation of particular deities, and thus lent itself to Jewish and Christian commemoration.[7] Early Christian writers transferred the imagery of garlands and crowns of roses and violets to the cult of the saints. Cultural and religious background In Greece and Rome, wreaths and garlands of flowers and greenery were worn by both men and women for festive occasions.[9] Garlands of roses and violets, combined or singly, adorn erotic scenes, bridal processions, and drinking parties in Greek lyric poetry from the Archaic period onward.[10] In Latin literature, to be "in the roses and violets" meant experiencing carefree pleasure.[11] Floral wreaths and garlands "mark the wearers as celebrants and likely serve as an expression of the beauty and brevity of life itself."[12] Roses and violets were the most popular flowers at Rome for wreaths, which were sometimes given as gifts.[13] Flowers were associated with or offered to some deities, particularly the goddesses Aphrodite (Roman Venus), Persephone[14] (Proserpina), and Chloris[15] (Flora). Roses and fragrances are a special attribute of Aphrodite,[16] and also of Dionysus, particularly in Imperial-era poetry as a wine god for drinking parties or with the presence of Eros ("Love, Desire").[17] The Greek romance novel Daphnis and Chloe (2nd century AD) describes a pleasure garden, with roses and violets among its abundant flora, centered on a sacred space for Dionysus.[18] At Rome Venus was a goddess of gardens as well as love and beauty.[19] Venus received roses at her ritual cleansing (lavatio) on April 1 and at the wine festival (Vinalia) celebrated in her honor April 23.[20] A lavish display of flowers was an expression of conviviality and liberal generosity. An Imperial-era business letter surviving on papyrus attempts to soothe a bridegroom's mother upset that the rose harvest was insufficient to fill her order for the wedding; the suppliers compensated by sending 4,000 narcissus instead of the 2,000 she requested.[21] While flowers were a part of Roman weddings, the bridegroom was more likely than the bride to wear a flower crown; Statius (1st century AD) describes a groom as wearing a wreath of roses, violets, and lilies.[22] When the emperor made a formal arrival (adventus) at a city, garlands of flowers might be among the gestures of greeting from the welcome delegation.[23] According to an account in the Historia Augusta ("presumably fictional"), the decadent emperor Heliogabalus buried the guests at one of his banquets in an avalanche of rose petals.[24] In Greek culture, the phyllobolia was the showering of a victorious athlete or bridal couple with leaves or flower petals.[25]  Classical mythology preserves a number of stories in which blood and flowers are linked in divine metamorphosis.[26] When Adonis, beloved of Aphrodite, was killed by a boar during a hunt, his blood produced a flower. A central myth of the Roman rites of Cybele is the self-castration of her consort Attis, from whose blood a violet-colored flower sprang. In the Gnostic text On the Origin of the World, possibly dating to the early 4th century,[27] the rose was the first flower to come into being, created from the virgin blood of Psyche ("Soul") after she united sexually with Eros.[28] In the 4th-century poem Cupid Crucified by the Gallo-Roman poet Ausonius, the god Cupid (the Roman equivalent of Eros) is tortured in the underworld by goddesses disappointed in love, and the blood from his wounds causes roses to grow.[29] In Egyptian religion, funerary wreaths of laurel, palm, feathers, papyrus, or precious metals represented the "crown of justification" that the deceased was to receive when he was judged in the Weighing of the Heart ceremony of the afterlife. In the Imperial period, the wreath might be roses, under the influence of the Romanized cult of Isis.[30] The statue of Isis was adorned with roses following the Navigium Isidis, an Imperial holiday March 5 when a ceremonial procession represented the "sailing" of Isis.[31] In the Metamorphoses of Apuleius, the protagonist Lucius is transformed into an ass, and after a journey of redemption returns to human form by eating roses and becoming an initiate into the mysteries of Isis.[26] A festival called the Rhodophoria, preserved in three Greek papyri, is the "rose-bearing" probably for Isis, or may be the Greek name for the Rosalia.[32] Roses and violets as funerary flowers Roses had funerary significance in Greece, but were particularly associated with death and entombment among the Romans.[34] In Greece, roses appear on funerary steles, and in epitaphs most often of girls.[35] In Imperial-era Greek epitaphs, the death of an unmarried girl is compared to a budding rose cut down in spring; a young woman buried in her wedding clothes is "like a rose in a garden"; an eight-year-old boy is like the rose that is "the beautiful flower of the Erotes" ("Loves" or Cupids).[36] As a symbol of both blooming youth and mourning, the rose often marks a death experienced as untimely or premature.[37] In the Iliad, Aphrodite anoints Hector's corpse with "ambrosial oil of roses"[38] to maintain the integrity of his body against abuse in death.[39] In Greek and Latin poetry, roses grow in the blessed afterlife of the Elysian Fields.[40] Bloodless sacrifice to the dead could include rose garlands and violets as well as libations of wine,[41] and Latin purpureus expressed the red-to-purple color range of roses and violets particularly as flowers of death.[37] In ancient etymology, purpureus was thought related to Greek porphyreos in the sense of suffusing the skin with purple blood in bruising or wounding.[37] The Augustan epic poet Vergil uses the metaphor of a purple flower to describe the premature, bloody deaths of young men in battle:[42] The death of Pallas evokes both the violet of Attis and the hyacinth generated from the dying blood of Apollo's beloved Hyacinthus.[43] Claudian writes of the "bloody splendor" of roses in the meadow from which Proserpina will be abducted to the underworld, with hyacinths and violets contributing to the lush flora.[44] Roses and the ominous presence of thorns may intimate bloodshed and mortality even in the discourse of love.[45]  Conversely, roses in a funerary context can allude to festive banqueting, since Roman families met at burial sites on several occasions throughout the year for libations and a shared meal that celebrated both the cherished memory of the beloved dead and the continuity of life through the family line.[46] In Roman tomb painting, red roses often spill bountifully onto light ground.[37] These ageless flowers created a perpetual Rosalia and are an expression of Roman beliefs in the soul's continued existence.[47] The bones or ashes of the deceased may be imagined as generating flowers, as in one Latin epitaph that reads:

Roses were planted at some tombs and mausoleums, and adjacent grounds might be cultivated as gardens to grow roses for adornment or even produce to sell for cemetery upkeep or administrative costs.[49] In the 19th to the 21st centuries, a profusion of cut and cultivated flowers was still a characteristic of Italian cemeteries to a degree that distinguished them from Anglo-American practice.[50] This difference is one of the Roman Catholic practices criticized by some Protestants, especially in the 19th century, as too "pagan" in origin.[51] Rose and violet festivals Although the rose had a long tradition in funerary art,[52] the earliest record of a Roman rose festival named as such dates to the reign of Domitian (81–96 AD),[53] and places the observance on June 20.[54] The inscription was made by a priestly association (collegium) in Lucania devoted to the woodland god Silvanus. It records vows for the wellbeing of the emperor and prescribes a sacrifice to Silvanus on five occasions in the year, among them the Rosalia. Although Silvanus is typically regarded as a deity of the woods and the wild, Vergil describes him as bearing flowering fennel and lilies.[55] In other inscriptions, three donors to Silvanus had adopted the cultic name Anthus (Greek anthos, "flower") and a fourth, of less certain reading, may have the Latin name Florus, the masculine form of Flora.[56] Since trees are the form of plant life most often emblematic of Silvanus, his connection with flowers is obscure. His female counterparts the Silvanae, primarily found in the Danubian provinces, are sometimes depicted carrying flower pots or wreaths.[57] Through his epithet Dendrophorus, "Tree-bearer," he was linked to the Romanized cult of Attis and Cybele in which celebrants called dendrophori participated.[58] When well-to-do people wrote a will and made end-of-life preparations, they might set aside funds for the maintenance of their memory and care (cura) after death, including rose-adornment. One epitaph records a man's provision for four annual observances in his honor: on the Parentalia, an official festival for honoring the dead February 13; his birthday (dies natalis); and a Rosaria and Violaria.[59] Guilds and associations (collegia) often provided funeral benefits for members, and some were formed specifically for that purpose. Benefactors might fund communal meals and rose-days at which members of the college honored the dead.[60] The College of Aesculapius and Hygia at Rome celebrated a Violet Day on March 22 and a Rose Day May 11, and these flower festivals are frequent among the occasions observed by dining clubs and burial societies.[61] Most evidence for the Rosalia comes from Cisalpine Gaul (northern Italy), where twenty-four Latin inscriptions referring to it have been found. Ten Latin inscriptions come from the Italian peninsula, three from Macedonia, and four from Thrace, Illyria, and Pannonia. Six Greek inscriptions come from Bithynia, three from Macedonia, and one each from Bulgaria, Scythia, Mysia, Phrygia, Lydia, Asia and Arcadia.[62]  At Pergamon, Rosalia seems to have been a three-day festival May 24–26, beginning with an "Augustan day" (dies Augusti, a day of Imperial cult marking a birthday, marriage, or other anniversary of the emperor or his family).[63] The three-day Rosalia was among the occasions observed by a group of hymnodes, a male choir organized for celebrating Imperial cult, as recorded in a Greek inscription on an early 2nd-century altar. The eukosmos, the officer of "good order" who presided over the group for a year, was to provide one mina (a monetary unit) and one loaf for celebrating the Rosalia on the Augustan day, which was the first day of the month called Panemos on the local calendar.[64] On the second of Panemos, the group's priest provided wine, a table setting, one mina, and three loaves for the Rosalia. The grammateus, a secretary or administrator, was responsible for a mina, a table setting worth one denarius, and one loaf for the third day of Rosalia.[65] The group seems to have functioned like a collegium at Rome, and as a burial society for members.[66] Inscriptions from Acmonia, in Phrygia, show the Rosalia in the context of the religious pluralism of the Roman Empire. In 95 AD, a bequest was made for a burial society to ensure the annual commemoration of an individual named Titus Praxias. In addition to a graveside communal meal and cash gifts to members, 12 denarii were to be allocated for adorning the tomb with roses. The obligations of membership were both legally and religiously binding: the society had its own tutelary deities who were invoked to oversee and ensure the carrying out of the deceased's wishes. These were Theos Sebastos (= Divus Augustus in Latin), Zeus under the local and unique epithet Stodmenos, Asclepius the Savior (Roman Aesculapius, as in the collegium above), and Artemis of Ephesus.[67] Acmonia also had a significant Greek-speaking Jewish community, and an inscription dating from the period 215–295 records similar arrangements made for a Jewish woman by her husband. It provides for an annual rose-adornment of the tomb by a legally constituted neighborhood or community association, with the solemn injunction "and if they do not deck it with roses each year, they will have to reckon with the justice of God."[68] The formula "he will have to reckon with God" was used only among Jews and Christians in Phrygia, and there is a slighter possibility that the inscription might be Christian.[69] The inscription is among the evidence that Judaism was not isolated from the general religious environment of the Imperial world, since a rosatio could be made without accompanying sacrifices at the tomb. Instead of multiple deities, the Jewish husband honoring his wife invoked the divine justice of his own God, and chose to participate in the customs of the community while adapting them in ways "acceptable to his Jewish faith".[70]  In Imperial-era Macedonia, several inscriptions mention the Rosalia as a commemorative festival funded by bequests to groups such as a vicianus, a village or neighborhood association (from vicus); thiasos, a legally constituted association, often having a religious character; or symposium, in this sense a drinking and social club. In Thessalonica, a priestess of a thiasos bequeathed a tract of grapevines to pay for rose wreaths.[71] If the Dionysian thiasos disbanded or failed in its duties, the property was to pass to a society of Dryophoroi ("Oak-Bearers"), or finally to the state.[72] In addition to associations of initiates into the mysteries of Dionysus, inscriptions in Macedonia and Thrace record bequests for rose-adornment to thiasoi of Diana (Artemis) and of the little-attested Thracian god or hero Sourogethes, and to a gravediggers' guild.[73] The gravediggers were to kindle a tombside fire each year for the Rosalia, and other contexts suggest that the wreaths themselves might be burnt as offerings.[74] A distinctive collocation that occurs a few times in Macedonian commemoration is an inscription prescribing the Rosalia accompanied by a relief of the Thracian Horseman.[75] Some scholars think that customs of the Rosalia were assimilated into Bacchic festivals of the dead by the Roman military, particularly in Macedonia and Thrace.[76] A Greek inscription of 138 AD records a donation for rose-adornment (rhodismos) to the council in Histria, in modern Dobruja, an area settled by the Thracian Bessi, who were especially devoted to Dionysus.[77] Macedonia was famed for its roses, but nearly all evidence for the Rosalia as such dates to the Roman period.[78] Bacchic ritesAlthough ivy and grapevines are the regular vegetative attributes of Dionysus, at Athens roses and violets could be adornments for Dionysian feasts. In a fragment from a dithyramb praising Dionysus, the poet Pindar (5th century BC) sets a floral scene generated by the opening up of the Seasons (Horae), a time when Semele, the mortal mother of Dionysus, is to be honored:

Dionysus was an equalizing figure of the democratic polis whose band of initiates (thiasos) provided a model for civic organizations.[81] A form of Dionysia dating to pre-democratic Athens was the Anthesteria, a festival name some scholars derive from Greek anthos, "flower, blossom",[82] as did the Greeks themselves, connecting it to the blossoming grapevine.[83] In the 6th century AD, the Byzantine antiquarian Joannes Lydus related the festival name to Anthousa, which he said was the Greek equivalent of the Latin Flora.[84] The three-day festival, which took place at the threshold between winter and spring, involved themes of liminality and "opening up", but despite its importance in early Athens, many aspects elude certainty. It was primarily a celebration of opening the new wine from the previous fall's vintage.[85] On the first day, "Dionysus" entered borne by a wheeled "ship" in a public procession, and was taken to the private chamber of the king's wife[86] for a ritual union with her; the precise ceremonies are unknown, but may be related to the myth of Ariadne, who became the consort of Dionysus after she was abandoned by the Athenian culture hero Theseus.[87]  In keeping with its theme of new growth and transformation,[88] the Anthesteria was also the occasion for a rite of passage from infancy to childhood—a celebratory moment given the high rate of infant mortality in the ancient world. Children between the age of three and four received a small jug (chous) specially decorated with scenes of children playing at adult activities. The chous itself is sometimes depicted on the vessel, adorned with a wreath. The following year, the child was given a ceremonial taste of wine from his chous.[89] These vessels are often found in children's graves, accompanying them to the underworld after a premature death.[90] The Anthesteria has also been compared with the Roman Lemuria,[91] with the second day a vulnerable time when the barrier between the world of the living and the dead became permeable, and the shades of the dead could wander the earth. On the third day, the ghosts were driven from the city, and Hermes Chthonios ("Underworld Hermes") received sacrifices in the form of pots of grains and seeds.[92] Although the identity of the shades is unclear, typically the restless dead are those who died prematurely.[93] Wine and rosesThe priestess of Thessalonica who bequeathed a tract of vineyard for the maintenance of her memory required each Dionysian initiate who attended to wear a rose wreath.[72] In a Dionysian context, wine, roses, and the color red are trappings of violence and funerals as well as amorous pursuits and revelry. Dionysus is described by Philostratus (d. ca. 250 AD) as wearing a wreath of roses and a red or purple cloak as he encounters Ariadne,[94] whose sleep is a kind of death from which she is awakened and transformed by the god's love.[95]  The crown that symbolized Ariadne's immortal union with Dionysus underwent metamorphosis into a constellation, the Corona Borealis; in some sources, the corona was a diadem of jewels, but for the Roman dramatist Seneca[96] and others it was a garland of roses. In the Astronomica of Manilius (1st century AD), Ariadne's crown is bejeweled with purple and red flowers—violets, hyacinths, poppies, and "the flower of the blooming rose, made red by blood"—and exerts a positive astrological influence on cultivating flower gardens, weaving garlands, and distilling perfume.[97] Dionysian scenes were common on Roman sarcophagi, and the persistence of love in the face of death may be embodied by attendant Cupids or Erotes.[98] In Vergil's Aeneid, purple flowers are strewn with the pouring of Bacchic libations during the funeral rites the hero Aeneas conducts for his dead father.[99] In the Dionysiaca of Nonnus (late 4th–early 5th century AD), Dionysus mourns the death of the beautiful youth Ampelos by covering the body with flowers—roses, lilies, anemones—and infusing it with ambrosia. The dead boy's metamorphosis creates the first grapevine, which in turn produces the transformative substance of wine for human use.[100] Rites of Adonis The rites of Adonis (Adoneia) also came to be regarded as a Rosalia in the Imperial era.[101] In one version of the myth, blood from Aphrodite's foot, pricked by a thorn, dyes the flowers produced from the body of Adonis when he is killed by the boar.[102] In the Lament for Adonis attributed to Bion (2nd century BC), the tears of Aphrodite match the blood shed by Adonis drop by drop,

According to myth, Adonis was born from the incestuous union of Myrrha and her father. The delusional lust was a punishment from Aphrodite, whom Myrrha had slighted. The girl deceived her father with darkness and a disguise, but when he learned who she really was, his rage transformed her human identity and she became the fragrance-producing myrrh tree. The vegetative nature of Adonis is expressed in his birth from the tree. In one tradition, Aphrodite took the infant, hid him in a box (larnax, a word often referring to chests for ash or other human remains), and gave him to the underworld goddess Persephone to nurture. When he grew into a beautiful youth, both Aphrodite and Persephone—representing the realms of love and death—claimed him. Zeus decreed that Adonis would spend a third of the year with the heavenly Aphrodite, a third with chthonic Persephone, and a third on the mortal plane. The theme is similar to Persephone's own year divided between her underworld husband and the world above.[104] For J.G. Frazer, Adonis was an archetypal vegetative god, and H.J. Rose saw in the rites of Adonis "the outlines of an Oriental myth of the Great Mother and of her lover who dies as the vegetation dies, but comes back to life again."[105] Robert A. Segal analyzed the death of Adonis as the failure of the "eternal child" (puer) to complete his rite of passage into the adult life of the city-state, and thus as a cautionary tale involving the social violations of "incest, murder, license, possessiveness, celibacy, and childlessness".[106]  Women performed the Adoneia with ceremonial lamentation and dirges, sometimes in the presence of an effigy of the dead youth that might be placed on a couch, perfumed, and adorned with greenery.[107] As part of the festival, they planted "gardens of Adonis", container-grown annuals from "seeds planted in shallow soil, which sprang up quickly and withered quickly",[108] compressing the cycle of life and death.[107] The festival, often nocturnal, was not a part of the official state calendar of holidays, and as a private rite seems like the Rosalia to have had no fixed date.[109] Although the celebration varied from place to place, it generally had two phases: joyful revelry like a marriage feast in celebration of the love between Aphrodite and Adonis, and ritual mourning for his death. Decorations and ritual trappings for the feast, including the dish gardens, were transformed for the funeral or destroyed as offerings: the garlanded couch became the lying-in bier (prothesis).[110] The iconography of Aphrodite and Adonis as a couple is often hard to distinguish in Greek art from that of Dionysus and Ariadne.[111] In contrast to Greek depictions of the couple enjoying the luxury and delight of love, Roman paintings and sarcophagi almost always frame their love at the moment of loss, with the death of Adonis in Aphrodite's arms posing the question of resurrection.[112] At Madaba, an Imperial city of the Province of Arabia in present-day Jordan, a series of mythological mosaics has a scene of Aphrodite and Adonis enthroned, attended by six Erotes and three Charites ("Graces"). A basket of overturned roses near them has been seen as referring to the Rosalia.[113] In late antiquity, literary works set at a Rosalia—whether intended for performance at the actual occasion, or only using the occasion as a fictional setting—take the "lament for Adonis" as their theme.[114] Shared language for the Roman festival of Rosalia and the floral aspects of the Adoneia may indicate similar or comparable practices, and not necessarily direct assimilation.[115] The violets of Attis From the reign of Claudius to that of Antoninus Pius, a "holy week" in March developed for ceremonies of the Magna Mater ("Great Mother", also known as Mater Deum, "Mother of the Gods," or Cybele) and Attis.[118] A preliminary festival on March 15 marked the discovery by shepherds or Cybele of the infant Attis among the reeds of a Phrygian river. The continuous ceremonies recommenced March 22 with the Arbor intrat ("The Tree enters") and lasted through March 27 or 28. For the day of Arbor intrat, the college of dendrophores ("tree-bearers") carried a pine tree to which was bound an effigy of Attis, wrapped in "woollen bandages like a corpse" and ornamented with violet wreaths.[119] Lucretius (1st century BC) mentions roses and other unnamed flowers in the ecstatic procession of the Magna Mater for the Megalensia in April.[120] The most vivid and complex account[121] of how the violet was created out of violence in the Attis myth is given by the Christian apologist Arnobius (d. ca. 330),[122] whose version best reflects cult practice in the Roman Imperial period.[123] The story begins with a rock in Phrygia named Agdus, from which had come the stones transformed to humans by Pyrrha and Deucalion to repopulate the world after the Flood. The Great Mother of the Gods customarily rested there, and there she was assailed by the lustful Jupiter. Unable to achieve his aim, the king of gods relieved himself by masturbating on the rock,[124] from which was born Acdestis or Agdistis, a violent and supremely powerful hermaphroditic deity. After deliberations, the gods assign the cura of this audacity to Liber, the Roman god identified with Dionysus: cura means variously "care, concern, cure, oversight." Liber sets a snare, replacing the waters of Agdistis's favorite spring (fons) with pure wine. Necessity in time drives the thirsty Agdistis to drink, veins sucking up the torpor-inducing liquid. The trap is sprung: a noose, woven from hair, suspends Agdistis by the genitals, and the struggle to break free causes a self-castration. From the blood springs a pomegranate tree, its fruit so enticing that Nana, the daughter of the river god Sangarius, in sinu reponit, a euphemism in Imperial-era medical and Christian writing for "placed within the vagina".[125] Nana becomes pregnant, enraging her father. He locks her away as damaged goods, and starves her. She is kept alive by fruits and other vegetarian food provided by the Mother of the Gods. When the infant is born, Sangarius orders that it be exposed, but it is discovered and reared by a goatherd. This child is Attis.  The exceptionally beautiful Attis grows up favored by the Mother of the Gods and by Agdistis, who is his constant companion. Under the influence of wine, Attis reveals that his accomplishments as a hunter are owing to divine favor—an explanation for why wine is religiously prohibited (nefas) in his sanctuary and considered a pollution for those who would enter. Attis's relationship with Agdistis is characterized as infamis, disreputable and socially marginalizing. The Phrygian king Midas, wishing to redeem the boy (puer), arranges a marriage with his daughter, and locks down the city. The Mater Deum, however, know Attis's fate (fatum): that he will be preserved from harm only if he avoids the bonds of marriage. Both the Mother of the Gods and Agdistis crash the party, and Agdistis spreads frenzy and madness among the convivial guests. In a detail that appears only in a vexed passage in the Christian source,[127] the daughter of a concubine to a man named Gallus cuts off her breasts. Raging like a bacchant, Attis then throws himself under a pine tree, and cuts off his genitals as an offering to Agdistis. He bleeds to death, and from the flux of blood is born a violet flower. The Mother of the Gods wraps the genitals "in the garment of the dead" and covers them with earth, an aspect of the myth attested in ritual by inscriptions regarding the sacrificial treatment of animal scrota.[128] The would-be bride, whose name is Violet (Greek Ia), covers Attis's chest with woollen bands, and after mourning with Agdistis kills herself. Her dying blood is changed into purple violets. The tears of the Mother of the Gods become an almond tree, which signifies the bitterness of death. She then takes the pine tree to her sacred cave, and Agdistis joins her in mourning, begging Jupiter to restore Attis to life. This he cannot permit; but fate allows the body to never decay, the hair to keep growing, and the little finger to live and to wave in perpetual motion. Arnobius explicitly states that the rituals performed in honor of Attis in his day reenact aspects of the myth as he has told it, much of which developed only in the Imperial period, in particular the conflict and intersections with Dionysian cult.[129] For the Arbor intrat on March 22, the dendrophores carried the violet-wreathed tree of Attis to the Temple of the Magna Mater. As a dies violae, the day of Arbor intrat recalled the scattering of violets onto graves for the Parentalia.[130] The next day the dendrophores laid the tree to rest with noisy music that represented the Corybantes, youths who performed armed dances and in mythology served as guardians for infant gods.[131] For the Dies Sanguinis ("Day of Blood") on March 24, the devotees lacerated themselves in a frenzy of mourning, spattering the effigy with the blood craved as "nourishment" by the dead. Some followers may have castrated themselves on this day, as a preliminary to becoming galli, the eunuch priests of Cybele. Attis was placed in his "tomb" for the Sacred Night that followed.[132] According to Sallustius, the cutting of the tree was accompanied by fasting, "as though we were cutting off the further progress of generation; after this we are fed on milk as though being reborn; that is followed by rejoicings and garlands and as it were a new ascent to the gods."[133] The garlands and rejoicing (Hilaria) occurred on March 25, the vernal equinox on the Julian calendar, when Attis was in some sense "reborn" or renewed.[134] Some early Christian sources associate this day with the resurrection of Jesus,[135] and Damascius saw it as a "liberation from Hades".[136] After a day of rest (Requietio), the ritual cleansing (Lavatio) of the Magna Mater was carried out on March 27.[137] March 28 may have been a day of initiation into the mysteries of the Magna Mater and Attis at the Vaticanum.[138] Although scholars have become less inclined to view Attis within the rigid schema of "dying and rising vegetation god", the vegetal cycle remains integral to the funerary nature of his rites.[139] The pine tree and pine cones were introduced to the iconography of Attis for their cult significance during the Roman period.[140] A late 1st- or 2nd-century statue of Attis from Athens has him with a basket containing pomegranates, pine cones, and a nosegay of violets.[141] Vegetal aspects of spring festivalsPerceived connections with older spring festivals that involved roses helped spread and popularize the Rosalia, and the private dies violae or violaris of the Romans was enhanced by the public prominence of Arbor intrat ceremonies.[142] The conceptual link between Attis and Adonis was developed primarily in the later Imperial period.[143] The Neoplatonic philosopher Porphyry (d. ca. 305 AD) saw both Adonis and Attis as aspects of the "fruits of the earth":

Porphyry linked Attis, Adonis, Korē (Persephone as "the Maiden", influencing "dry" or grain crops), and Dionysus (who influences soft and shell fruits) as deities of "seminal law":

Roses and violets are typically among the flower species that populate the meadow from which Persephone was abducted as Pluto's bride.[145] The comparative mythologist Mircea Eliade saw divine metamorphosis as a "flowing of life" between vegetal and human existence. When violent death interrupts the creative potential of life, it is expressed "in some other form: plant, fruit, flower". Eliade related the violets of Attis and the roses and anemones of Adonis to legends of flowers appearing on battlefields after the deaths of heroes.[146] Military Rosaliae The Roman army celebrated the Rosaliae signorum, when the military standards (signa) were adorned with roses in a supplication, on two dates in May. A.H. Hooey viewed the military rose festival as incorporating traditional spring festivals of vegetative deities.[147] The festival is noted in the Feriale Duranum, a papyrus calendar for a cohort stationed at Dura-Europos during the reign of Severus Alexander (224–235 AD). The calendar is thought to represent a standard religious calendar issued to the military.[148] The day of the earlier of the two Rosaliae is uncertain because of the fragmentary text, but coincided with the period of the Lemuria, archaic festival days on May 9, 11, and 13[149] for propitiating shades (lemures or larvae) of those whose untimely death left them wandering the earth instead of passing into the underworld. The ceremonies of the Lemuria, in the vivid description of Ovid, featured the spitting of black beans as an especially potent apotropaic gesture.[150] The second of the Rosaliae signorum occurred on May 31, the day before the Kalends of June.[151] The feast day of June 1, devoted to the tenebrous Dea Carna ("Flesh Goddess" or "Food Goddess") and commonly called the "Bean Kalends" (Kalendae Fabariae),[152] may have pertained to rites of the dead[153] and like the days of the Lemuria was marked on the calendar as nefastus, a time when normal activities were religiously prohibited. In the later Empire, the Rosaliae signorum coincided with the third day of the "Bean Games" (Ludi Fabarici) held May 29 – June 1, presumably in honor of Carna.[154] A civilian inscription records a bequest for rose-adornment "on the Carnaria", interpreted by Mommsen as Carna's Kalends.[155] Sculpture from a 3rd-century military headquarters at Coria, in Roman Britain (Corbridge, Northumberland), has been interpreted as representing the Rosaliae.[156] A 3rd-century inscription from Mogontiacum (present-day Mainz), in the province of Germania Superior, records the dedication of an altar to the Genius of the military unit (a centuria), on May 10. Although the inscription does not name the Rosaliae, the date of the dedication, made in connection with Imperial cult, may have been chosen to coincide with it.[157]  The Rosaliae signorum were part of devotional practices characteristic of the army surrounding the military standards. The Imperial historian Tacitus says that the army venerated the standards as if they were gods, and inscriptions record dedications (vota) made on their behalf.[158] The day on which a legion marked the anniversary of its formation was the natalis aquilae, "the Eagle's birthday," in reference to the Roman eagle of the standard.[159] All Roman military camps, including marching camps, were constructed around a central altar where daily sacrifices were made, surrounded by the standards planted firmly into the ground[160] and by images of emperors and gods.[161] Decorated units displayed gold and silver wreaths on their standards that represented the bestowal of living wreaths, and the Eagles and other signa were garlanded and anointed for lustrations, ceremonies for beginning a campaign, victories, crisis rituals, and Imperial holidays.[162] Among these occasions was the wedding of the emperor Honorius in 398 AD, described in an epithalamium by Claudian: the military standards are said to grow red with flowers, and the standard-bearers and soldiers ritually shower the imperial bridegroom with flowers purpureoque ... nimbo, in a purple halo.[163] In recounting a mutiny against Claudius in 42 AD, Suetonius avers that divine agency prevented the Eagles from being adorned or pulled from the earth to break camp by the legionaries who had violated their oath (sacramentum); reminded of their religious obligation, they were turned toward repentance (in paenitentiam religione conversis).[164] Christian apologists saw the veneration of the signa as central to the religious life of the Roman military, and Minucius Felix tried to demonstrate that because of the cruciform shape, the soldiers had been worshipping the Christian cross without being aware of it.[165] Most evidence of the Rosalia from the Empire of the 1st–3rd centuries points toward festivals of the dead. Soldiers commemorated fallen comrades,[166] and might swear an oath on the manes (deified spirits) of dead brothers-in-arms.[167] Hooey, however, argued against interpreting the Rosaliae signorum as a kind of "poppy day". Roman rose festivals, in his view, were of two distinct and mutually exclusive kinds: the celebratory and licentious festivals of spring, and the somber cult of the dead. Transferred from the civilian realm, the old festivals of vegetative deities were celebrated in the Eastern Empire in a spirit of indulgence and luxury that was uniquely out of keeping with the public and Imperial character of other holidays on the Feriale Duranum.[168] This "carnival" view of the Rosaliae signorum was rejected by William Seston, who saw the May festivals as celebratory lustrations after the first battles of the military campaigning season, coordinate with the Tubilustrium that fell on May 23 between the two rose-adornments.[169]  The Tubilustrium was itself a purification ritual. Attested on calendars for both March 23 and May 23, it was perhaps originally monthly. The lustration (lustrum) was performed regarding the annunciatory trumpets (tubi or tubae, a long straight trumpet, and cornua, which curved around the body) that were used to punctuate sacral games and ceremonies, funerals,[170] and for signals and timekeeping in the military.[171] The March 23 Tubilustrium coincided in the city of Rome with a procession of Mars' armed priests the Salii, who clanged their sacred shields. In the later Empire, it had become assimilated into the "holy week" of Attis, occurring on the day when the tree rested at the Temple of the Magna Mater. As a pivotal point in the cycle of death/chaos and (re)birth/order, the day brought together noise rituals of wind and percussion instruments from different traditions, the clamor of the Corybantes or Kouretes who attended Cybele and Attis, and Roman ceremonies of apotropaic trumpet blasts or the beating of shields by the Salian priests,[172] who were theologically identified with the Kouretes as early as the 1st century BC.[173] Tacitus records the performance of noise rituals on the trumpets by the military in conjunction with a lunar eclipse.[174] The practice is found in other sources in a civilian context.[175] Jörg Rüpke conjectures that the tubae were played monthly "to fortify the waning moon (Luna)", one nundinal cycle after the full moon of the Ides, since the Roman calendar was originally lunar.[176] The signa and the trumpets were closely related in Roman military culture, both ceremonially and functionally, and on Trajan's Column the trumpets are shown pointing toward the standards during lustrations.[177] Although Latin lustratio is usually translated as "purification", lustral ceremonies should perhaps be regarded as realignments and restorations of good order: "lustration is another word for maintaining, creating or restoring boundary lines between the centric order and the ex-centric disorder".[178] The Rosaliae of the standards in May were contingent on supplicationes, a broad category of propitiatory ritual that realigned the community, in this case the army, with the pax deorum, the "treaty" or peace of the gods, by means of a procession, public prayers, and offerings. The military calendar represented by the Feriale Duranum prescribed supplicationes also for March 19–23, the period that began with the Quinquatria, an ancient festival of Minerva and Mars, and concluded with a Tubilustrium. The Crisis of the Third Century prompted a revival and expansion of the archaic practice of supplicatio in connection with military and Imperial cult.[179] On the calendar In the later Empire, rose festivals became part of the iconography for the month of May. The date would vary locally to accommodate the blooming season.[181] For month allegories in mosaics, May is often represented with floral wreaths, the fillets or ribbons worn for sacrifice, and wine amphorae.[182] May (Latin Maius) began in the middle of the Ludi Florae, a series of games in honor of the goddess Flora that opened April 28 of the Julian calendar and concluded May 3. Flora was a goddess of flowers and blooming, and her festivities were enjoyed with a notable degree of sexual liberty. In the 2nd century AD, Philostratus connects rose garlands with Flora's festival.[183] A Greek epigram from the Palatine Anthology has May personified announce "I am the mother of roses".[184] Among explanations for the month's name was that it derived from Maia, a goddess of growth or increase whose own name was sometimes said to come from the adjective maius, "greater". Maia was honored in May with her son Mercury (Greek Hermes), a god of boundaries and commerce, and a conductor of souls to the afterlife. The theological identity of Maia was capacious; she was variously identified with goddesses such as Terra Mater ("Mother Earth"), the Good Goddess (Bona Dea), the Great Mother Goddess (Magna Mater, a title also for Cybele), Ops ("Abundance, Resources"), and Carna, the goddess of the Bean Kalends on June 1.[185] Roses were distributed to the Arval Brothers, an archaic priesthood of Rome, after their banquets for the May festival of Dea Dia.[186]  Although the month opened with the revelry of Flora, in mid-May the Romans observed the three-day Lemuria for propitiating the wandering dead.[187] The season of roses thus coincided with traditional Roman festivals pertaining to blooming and dying. The demand for flowers and perfumes for festal and funerary purposes made floriculture an important economic activity, especially for the rich estates of Roman Africa.[188] One Roman tomb painting shows vendors displaying floral garlands for sale.[189] Following the Lemuria, Mercury and Maia received a joint sacrifice during a merchants' festival on the Ides of May (the 15th). The Calendar of Filocalus (354 AD) notes a flower fair on May 23, when the roses come to market (macellus).[190] The month is illustrated for this calendar with a king of roses: a young man, wearing the long-sleeved robe called a dalmatica, carries a basket of roses on his left arm while holding a single flower in his right hand to smell.[182] In other pictorial calendars, the Rose King or related imagery of the rose festival often substitutes for or replaces the traditional emblem of Mercury and his rites to represent May.[191] In Ovid's Fasti, a poem about the Roman calendar, Flora as the divine representative of May speaks of her role in generating flowers from the blood of the dead: "through me glory springs from their wound".[192] Ovid shows how her mythology weaves together themes of "violence, sexuality, pleasure, marriage, and agriculture."[193] The Romans considered May an unpropitious month for weddings, a postponement that contributed to the popularity of June as a bridal month. Each day of the Lemuria in mid-May was a dies religiosus, when it was religiously prohibited to begin any new undertaking, specifically including marriage "for the sake of begetting children".[194] In the 4th century, the Rosalia was marked on the official calendar as a public holiday at the amphitheater with games (ludi) and theatrical performances. A calendar from Capua dating to 387 AD notes a Rosaria at the amphitheater on May 13.[195] Christianization In the 6th century, a "Day of Roses" was held at Gaza, in the Eastern Roman Empire, as a spring festival that may have been a Christianized continuation of the Rosalia.[196] John of Gaza wrote two anacreontic poems that he says he presented publicly on "the day of the roses", and declamations by the Christian rhetorician Procopius[197] and poetry by Choricius of Gaza are also set at rose-days.[198] Roses were in general part of the imagery of Early Christian funerary art,[199] as was ivy.[200] Martyrs were often depicted or described with flower imagery, or in ways that identified them with flowers.[29] Paulinus of Nola (d. 431) reinterpreted traditions associated with the Rosalia in Christian terms for his natal poem (natalicium) about Saint Felix of Nola, set January 14:[201]

At one of the earliest extant martyr shrines, now part of the Basilica of Sant'Ambrogio in Milan, a mosaic portrait dating perhaps as early as 397–402 depicts Saint Victor within a classically inspired wreath of lilies and roses, wheat stalks, grapes on the vine, and olive branches: the circular shape represents eternity, and the vegetation the four seasons.[203] In the Christian imagination, the blood-death-flower pattern is often transferred from the young men of Classical myth—primarily Adonis and Attis—to female virgin martyrs.[204] Eulalia of Mérida is described by Prudentius (d. ca. 413) as a "tender flower" whose death makes her "a flower in the Church's garland of martyrs": the flow of her purple blood produces purple violets and blood-red crocuses (purpureas violas sanguineosque crocos), which will adorn her relics.[205] The rose can also symbolize the blood shed with the loss of virginity in the sacrament of marriage.[206] Drawing on the custom of floral crowns as awards in the Classical world, Cyprian (d. 258) described heavenly crowns of flowers for the faithful in the afterlife: lilies for those who did good works, and an additional crown of roses for martyrs.[207] In one early passion narrative, a martyr wears a rose crown (corona rosea) at a heavenly banquet.[208] For Ambrose (d. 397), lilies were for virgins, violets for confessors of the faith, and roses for martyrs;[209] of these, the imagery of the violet has no biblical precedent.[210] In a passage influenced by Vergilian imagery, Ambrose enjoins young women who are virgins to "Let the rose of modesty and the lily of the spirit flourish in your gardens, and let banks of violets drink from the spring that is watered by the sacred blood."[211] In the description of Jerome (d. 420), "a crown of roses and violets" is woven from the blood of Saint Paula's martyrdom.[212] Dante later entwines Classical and Christian strands of imagery in his Paradiso, linking the garland of saints with the rose corona of Ariadne, whom he imagines as translated to the heavens by it.[213] The use of the term "rosary" (Latin rosarium, a crown or garland of roses) for Marian prayer beads was objected to by some Christians, including Alanus de Rupe, because it evoked the "profane" rose wreath of the Romans.[214]  Miracles involving roses are ascribed to some female saints, while roses are a distinguishing attribute of others ranging from Cecilia of Rome (d. 230 AD) to Thérèse of Lisieux (d. 1897).[216] The floral iconography of Saint Cecilia includes a rose or floral wreath, a palm branch, and a "tall sprig of almond leaves and flowers in her hand".[217] Roses are among the most characteristic attributes of Mary, mother of Jesus, who became associated with the month of May,[218] replacing goddesses such as Maia and Flora in the popular imagination.[219] Mary is described in early Christian literature as a rosa pudoris, "rose of modesty",[220] and a rose among thorns.[221] In the Middle Ages, roses, lilies and violets become the special flowers of Mary.[222] In some Catholic cultures, offerings of flowers are still made to Mary, notably in Mexican devotional practices for Our Lady of Guadalupe.[223] On the island of Pollap, in Micronesia, offerings of flowers before the cult statue of Mary are added to ceremonies of the rosary especially for May; the concept of the rosary as a "crown of roses" complements local traditions of wearing a flower wreath on the head.[224] Latin hymns and litanies from the earliest Christian era name Mary as the "Mystical Rose" and by an array of rose epithets, or as a garden that bore Christ in the image of the rose.[225] Ambrose declared that the blood of Christ in the Eucharist, transubstantiated from wine, was to be perceived as a rose.[226] The five-petaled rose became a symbol of the Five Wounds of Christ and hence of the Resurrection.[227] The living bodies and corpses of saints were said to exude a floral "odor of sanctity" as one of the most notable signs of their holiness.[228] Pope Gregory I described the fragrance and luminosity of the rose as issuing from the blood of martyrs.[229] Herman of Steinfeld exhaled a fragrance "like a garden full of roses, lilies, violets, poppies and all kinds of fragrant flowers" as he prayed.[230] The bedridden virgin Lydwine of Schiedam was said to consume nothing but spiced wine, and wept "fragrant tears of blood" which she called her roses; when these dried on her cheeks overnight, they were gathered and kept in a box. The omen of her death was the opening of roses on a mystical rosebush, and when she was buried the bag of rose blood-tears was used as her pillow.[231] Flowers, blood, and relics were interwoven in the imagery of Christian literature from the earliest period.[232] Rose Sundays Two days of the liturgical calendar have been called "Rose Sunday":

See also

References

|

||||||||||||