|

Elagabalus

Marcus Aurelius Antoninus (born Sextus Varius Avitus Bassianus, c. 204 – 13 March 222), better known by his posthumous nicknames Elagabalus (/ˌɛləˈɡæbələs/ EL-ə-GAB-ə-ləs) and Heliogabalus (/ˌhiːliə-, -lioʊ-/ HEE-lee-ə-, -lee-oh-[3]), was Roman emperor from 218 to 222, while he was still a teenager. His short reign was notorious for religious controversy and alleged sexual debauchery. A close relative to the Severan dynasty, he came from a prominent Syrian Arab family in Emesa (Homs), Syria, where he served as the head priest of the sun god Elagabal from a young age. After the death of his cousin, the emperor Caracalla, Elagabalus was raised to the principate at 14 years of age in an army revolt instigated by his grandmother Julia Maesa against Caracalla's short-lived successor, Macrinus. He only posthumously became known by the Latinised name of his god.[a] Elagabalus is largely known from accounts by the contemporary senator Cassius Dio who was strongly hostile to him, and the much later Historia Augusta. The reliability of these accounts, particularly their most salacious elements, has been strongly questioned.[5][6] Elagabalus showed a disregard for Roman religious traditions. He brought the cult of Elagabal (including the large baetyl stone the god was represented by) to Rome, making it a prominent part of religious life in the city. He forced leading members of Rome's government to participate in religious rites celebrating this deity, presiding over them in person. According to the accounts of Cassius Dio and the Augusta, he married four women, including a Vestal Virgin, in addition to lavishing favours on male courtiers they suggested to have been his lovers,[7][8] and prostituted himself.[9] His behavior estranged the Praetorian Guard, the Senate, and the common people alike. Amidst growing opposition, at just 18 years of age he was assassinated and replaced by his cousin Severus Alexander in March 222. The assassination plot against Elagabalus was devised by Julia Maesa and carried out by disaffected members of the Praetorian Guard. Elagabalus developed a posthumous reputation for extreme eccentricity, decadence, zealotry, and sexual promiscuity. Among writers of the early modern age, he endured one of the worst reputations among Roman emperors. Edward Gibbon, notably, wrote that Elagabalus "abandoned himself to the grossest pleasures with ungoverned fury".[10] According to Barthold Georg Niebuhr, "the name of Elagabalus is branded in history above all others; [...] "Elagabus had nothing at all to make up for his vices, which are of such a kind that it is too disgusting even to allude to them".[11] An example of a modern historian's assessment is Adrian Goldsworthy's: "Elagabalus was not a tyrant, but he was an incompetent, probably the least able emperor Rome had ever had".[12] Despite near-universal condemnation of his reign, some scholars write warmly about his religious innovations, including the 6th-century Byzantine chronicler John Malalas, as well as Warwick Ball, a modern historian who described him as "a tragic enigma lost behind centuries of prejudice".[13] Modern scholars have questioned the accuracy of Roman accounts of his reign, with suggestions that the reports of his salacious and homosexual behaviour may have been related to Roman stereotypes regarding people from the Orient as effeminate.[5][14] Family and priesthoodA sculpture of Julia Soaemias Elagabalus was born in 203 or 204,[b] to Sextus Varius Marcellus and Julia Soaemias Bassiana,[17] who had probably married around the year 200 (and no later than 204).[18][19] Elagabalus's full birth name was probably (Sextus) Varius Avitus Bassianus,[c] the last name being apparently a cognomen of the Emesene dynasty.[20] Marcellus was an equestrian, later elevated to a senatorial position.[17][21][18] Julia Soaemias was a cousin of the emperor Caracalla, and there were rumors (which Soaemias later publicly supported) that Elagabalus was Caracalla's child.[21][22] Marcellus's tombstone attests that Elagabalus had at least one brother,[23][24] about whom nothing is known.[19] Elagabalus's grandmother, Julia Maesa, was the widow of the consul Julius Avitus Alexianus, the sister of Julia Domna, and the sister-in-law of the emperor Septimius Severus.[17][18] Other relatives included Elagabalus's aunt Julia Avita Mamaea and uncle Marcus Julius Gessius Marcianus and their son Severus Alexander.[17] Elagabalus's family held hereditary rights to the priesthood of the sun god Elagabal, of whom Elagabalus was the high priest at Emesa (modern Homs) in Roman Syria as part of the Arab Emesene dynasty.[25] The deity's Latin name, "Elagabalus", is a Latinized version of the Arabic إِلٰهُ الْجَبَلِ Ilāh al-Jabal, from ilāh ("god") and jabal ("mountain"), meaning "God of the Mountain",[26] the Emesene manifestation of Ba'al.[27] Initially venerated at Emesa, the deity's cult spread to other parts of the Roman Empire in the second century; a dedication has been found as far away as Woerden (in the Netherlands), near the Roman limes.[28] The god was later imported to Rome and assimilated with the sun god known as Sol Indiges in the era of the Roman Republic and as Sol Invictus during the late third century.[29] In Greek, the sun god is Helios, hence Elagabal was later known as "Heliogabalus", a hybrid of "Helios" and "Elagabalus".[30] Rise to powerHerodian writes that when the emperor Macrinus came to power, he suppressed the threat to his reign from the family of his assassinated predecessor, Caracalla, by exiling them—Julia Maesa, her two daughters, and her eldest grandson Elagabalus—to their estate at Emesa in Syria.[31] Almost upon arrival in Syria, Maesa began a plot with her advisor and Elagabalus's tutor, Gannys, to overthrow Macrinus and elevate the fourteen-year-old Elagabalus to the imperial throne.[31] Maesa spread a rumor, which Soaemias publicly supported, that Elagabalus was the illegitimate child of Caracalla[22][32] and so deserved the loyalty of Roman soldiers and senators who had sworn allegiance to Caracalla.[33] The soldiers of the Third Legion Gallica at Raphana, who had enjoyed greater privileges under Caracalla and resented Macrinus (and may have been impressed or bribed by Maesa's wealth), supported this claim.[21][32][34] At sunrise on 16 May 218,[35] Elagabalus was declared emperor by Publius Valerius Comazon, commander of the legion.[36] To strengthen his legitimacy, Elagabalus adopted the same name Caracalla bore as emperor, Marcus Aurelius Antoninus.[37][38] Cassius Dio states that some officers tried to keep the soldiers loyal to Macrinus, but they were unsuccessful.[21]  Praetorian prefect Ulpius Julianus responded by attacking the Third Legion, most likely on Macrinus's orders (though one account says he acted on his own before Macrinus knew of the rebellion).[39] Herodian suggests Macrinus underestimated the threat, considering the rebellion inconsequential.[40] During the fighting, Julianus's soldiers killed their officers and joined Elagabalus's forces.[37] Macrinus asked the Roman Senate to denounce Elagabalus as "the False Antoninus", and they complied,[41] declaring war on Elagabalus and his family.[34] Macrinus made his son Diadumenian co-emperor, and attempted to secure the loyalty of the Second Legion with large cash payments.[42][43] During a banquet to celebrate this at Apamea, however, a messenger presented Macrinus with the severed head of his defeated prefect Julianus.[42][43][44] Macrinus therefore retreated to Antioch, after which the Second Legion shifted its loyalties to Elagabalus.[42][43] Elagabalus's legionaries, commanded by Gannys, defeated Macrinus and Diadumenian and their Praetorian Guard at the Battle of Antioch on 8 June 218, prevailing when Macrinus's troops broke ranks after he fled the battlefield.[45] Macrinus made for Italy, but was intercepted near Chalcedon and executed in Cappadocia, while Diadumenian was captured at Zeugma and executed.[42] That month, Elagabalus wrote to the Senate, assuming the imperial titles without waiting for senatorial approval,[46] which violated tradition but was a common practice among third-century emperors.[47] Letters of reconciliation were dispatched to Rome extending amnesty to the Senate and recognizing its laws, while also condemning the administration of Macrinus and his son.[48] The senators responded by acknowledging Elagabalus as emperor and accepting his claim to be the son of Caracalla.[47] Elagabalus was made consul for the year 218 in the middle of June.[49] Caracalla and Julia Domna were both deified by the Senate, both Julia Maesa and Julia Soaemias were elevated to the rank of Augustae,[50] and the memory of Macrinus was expunged by the Senate.[47] (Elagabalus's imperial artifacts assert that he succeeded Caracalla directly.)[51] Comazon was appointed commander of the Praetorian Guard.[52][53] Elagabalus was named Pater Patriae by the Senate before 13 July 218.[49] On 14 July, Elagabalus was inducted into the colleges of all the Roman priesthoods, including the College of Pontiffs, of which he was named pontifex maximus.[49] Emperor (218–222)Journey to Rome and political appointments   Elagabalus stayed for a time at Antioch, apparently to quell various mutinies.[54] Dio outlines several, which historian Fergus Millar places prior to the winter of 218–219.[55] These included one by Gellius Maximus, who commanded the Fourth Legion and was executed,[55] and one by Verus, who commanded the Third Legion Gallica, which was disbanded once the revolt was put down.[56] Next, according to Herodian, Elagabalus and his entourage spent the winter of 218–219 in Bithynia at Nicomedia, and then traveled through Thrace and Moesia to Italy in the first half of 219,[54] the year of Elagabalus's second consulship.[49] Herodian says that Elagabalus had a painting of himself sent ahead to Rome to be hung over a statue of the goddess Victoria in the Senate House so people would not be surprised by his Eastern garb, but it is unclear if such a painting actually existed, and Dio does not mention it.[57][58] If the painting was indeed hung over Victoria, it put senators in the position of seeming to make offerings to Elagabalus when they made offerings to Victoria.[56] On his way to Rome, Elagabalus and his allies executed several prominent supporters of Macrinus, such as Syrian governor Fabius Agrippinus and former Thracian governor C. Claudius Attalus Paterculianus.[59] Arriving at the imperial capital in August or September 219, Elagabalus staged an adventus, a ceremonial entrance to the city.[49] In Rome, his offer of amnesty for the Roman upper class was largely honored, though the jurist Ulpian was exiled.[60] Elagabalus made Comazon praetorian prefect, and later consul (220) and prefect of the city (three times, 220–222), which Dio regarded as a violation of Roman norms.[59] Elagabalus himself held a consulship for the third year in a row in 220.[49] Herodian and the Augustan History say that Elagabalus alienated many by giving powerful positions to other allies.[61] He developed the imperial palace at Horti Spei Veteris with the inclusion of the nearby land inherited from his father Sextus Varius Marcellus. Elagabalus made it his favourite retreat and designed it (as for Nero's Domus Aurea project) as a vast suburban villa divided into various building and landscape nuclei with the Amphitheatrum Castrense which he built and the Circus Varianus hippodrome[62] fired by his unbridled passion for circuses and his habit of driving chariots inside the villa. He raced chariots under the family name of Varius.[63] Dio states that Elagabalus wanted to marry a charioteer named Hierocles and to declare him caesar,[55] just as (Dio says) he had previously wanted to marry Gannys and name him caesar.[55] The athlete Aurelius Zoticus is said by Dio to have been Elagabalus's lover and cubicularius (a non-administrative role), while the Augustan History says Zoticus was a husband to Elagabalus and held greater political influence.[64] Elagabalus's relationships to his mother Julia Soaemias and grandmother Julia Maesa were strong at first; they were influential supporters from the beginning, and Macrinus declared war on them as well as Elagabalus.[65] Accordingly, they became the first women allowed into the Senate,[66] and both received senatorial titles: Soaemias the established title of Clarissima, and Maesa the more unorthodox Mater Castrorum et Senatus ("Mother of the army camp and of the Senate").[50] They exercised influence over the young emperor throughout his reign, and are found on many coins and inscriptions, a rare honour for Roman women.[67] Under Elagabalus, the gradual devaluation of Roman aurei and denarii continued (with the silver purity of the denarius dropping from 58% to 46.5%),[68] though antoniniani had a higher metal content than under Caracalla.[69] Religious controversy  Since the reign of Septimius Severus, sun worship had increased throughout the Empire.[70] At the end of 220, Elagabalus instated Elagabal as the chief deity of the Roman pantheon, possibly on the date of the winter solstice.[49] In his official titulature, Elagabalus was then entitled in Latin: sacerdos amplissimus dei invicti Soli Elagabali, pontifex maximus, lit. 'highest priest of the unconquered god, the Sun Elgabal, supreme pontiff'.[49] That a foreign god should be honored above Jupiter, with Elagabalus himself as chief priest, shocked many Romans.[71] As a token of respect for Roman religion, however, Elagabalus joined either Astarte, Minerva, Urania, or some combination of the three to Elagabal as consort.[72] A union between Elagabal and a traditional goddess would have served to strengthen ties between the new religion and the imperial cult. There may have been an effort to introduce Elagabal, Urania, and Athena as the new Capitoline Triad of Rome—replacing Jupiter, Juno, and Minerva.[73] He aroused further discontent when he married the Vestal Virgin Aquilia Severa, Vesta's high priestess, claiming the marriage would produce "godlike children".[74] This was a flagrant breach of Roman law and tradition, which held that any Vestal found to have engaged in sexual intercourse was to be buried alive.[75] A lavish temple called the Elagabalium was built on the east face of the Palatine Hill to house Elagabal,[76] who was represented by a black conical meteorite from Emesa.[48] This was a baetyl. Herodian wrote "this stone is worshipped as though it were sent from heaven; on it there are some small projecting pieces and markings that are pointed out, which the people would like to believe are a rough picture of the sun, because this is how they see them".[77] Dio writes that in order to increase his piety as high priest of Elagabal atop a new Roman pantheon, Elagabalus had himself circumcised and swore to abstain from swine.[76] He forced senators to watch while he danced circling the altar of Elagabal to the accompaniment of drums and cymbals.[77] Each summer solstice he held a festival dedicated to the god, which became popular with the masses because of the free food distributed on these occasions.[78] During this festival, Elagabalus placed the black stone on a chariot adorned with gold and jewels, which he paraded through the city:[79]

The most sacred relics from the Roman religion were transferred from their respective shrines to the Elagabalium, including the emblem of the Great Mother, the fire of Vesta, the Shields of the Salii, and the Palladium, so that no other god could be worshipped except in association with Elagabal.[81] Although his native cult was widely ridiculed by contemporaries, sun-worship was popular among the soldiers and would be promoted by several later emperors.[82] Marriages, sexual orientation and gender identity The question of Elagabalus's sexual orientation and gender identity is confused, owing to salacious and unreliable sources. Cassius Dio states that Elagabalus was married five times (twice to the same woman).[57] His first wife was Julia Cornelia Paula, whom he married prior to 29 August 219; between then and 28 August 220, he divorced Paula, took the Vestal Virgin Julia Aquilia Severa as his second wife, divorced her,[57][83] and took a third wife, who Herodian says was Annia Aurelia Faustina, a descendant of Marcus Aurelius and the widow of a man Elagabalus had recently executed, Pomponius Bassus.[57] In the last year of his reign, Elagabalus divorced Annia Faustina and remarried Aquilia Severa.[57] Dio states that another "husband of this woman [Elagabalus] was Hierocles", an ex-slave and chariot driver from Caria.[8][84] The Augustan History claims that Elagabalus also married a man named Zoticus, an athlete from Smyrna, while Dio says only that Zoticus was his cubicularius.[8][85] Dio says that Elagabalus prostituted himself in taverns and brothels.[9] Some writers suggest that Elagabalus may have identified as female or been transgender, and may have sought sex reassignment surgery.[86][87][88][89][90] Dio says Elagabalus delighted in being called Hierocles's mistress, wife, and queen.[88] The emperor reportedly wore makeup and wigs, preferred to be called a lady and not a lord, and supposedly offered vast sums to any physician who could provide him with a vagina by means of incision.[88][91] Some historians, including the classicists Mary Beard, Zachary Herz, and Martijn Icks, treat these accounts with caution, as sources for Elagabalus' life were often antagonistic towards him and largely untrustworthy.[92][93] In November 2023, the North Hertfordshire Museum in Hitchin, United Kingdom, announced that Elagabalus would be considered as transgender and hence referred to with female pronouns in its exhibits due to claims that the emperor had said "call me not Lord, for I am a Lady". The museum has one Elagabalus coin.[93][94] Fall from powerElagabalus stoked the animus of Roman elites and the Praetorian Guard through his perceptibly foreign conduct and his religious provocations.[95] When Elagabalus's grandmother Julia Maesa perceived that popular support for the emperor was waning, she decided that he and his mother, who had encouraged his religious practices, had to be replaced. As alternatives, she turned to her other daughter, Julia Avita Mamaea, and her daughter's son, the fifteen-year-old Severus Alexander.[96] Prevailing on Elagabalus, she arranged that he appoint his cousin Alexander as his heir and that the boy be given the title of caesar.[96] Alexander was elevated to caesar in June 221, possibly on 26 June.[49] Elagabalus and Alexander were each named consul designatus for the following year, probably on 1 July.[49] Elagabalus took up his fourth consulship for the year of 222.[49] Alexander shared the consulship with the emperor that year.[96] However, Elagabalus reconsidered this arrangement when he began to suspect that the Praetorian Guard preferred his cousin to himself.[97] Elagabalus ordered various attempts on Alexander's life,[98] after failing to obtain approval from the Senate for stripping Alexander of his shared title.[99] According to Dio, Elagabalus invented the rumor that Alexander was near death, in order to see how the Praetorians would react.[100] A riot ensued, and the Guard demanded to see Elagabalus and Alexander in the Praetorian camp.[100]  On 13 March,[d] the emperor complied and publicly presented his cousin along with his own mother, Julia Soaemias. On their arrival the soldiers started cheering Alexander while ignoring Elagabalus, who ordered the summary arrest and execution of anyone who had taken part in this display of insubordination.[102] In response, members of the Praetorian Guard attacked Elagabalus and his mother:

Following his assassination, many associates of Elagabalus were killed or deposed. His lover Hierocles was executed.[100] His religious edicts were reversed and the stone of Elagabal was sent back to Emesa.[104] Women were again barred from attending meetings of the Senate.[105] The practice of damnatio memoriae—erasing from the public record a disgraced personage formerly of note—was systematically applied in his case.[49][106] Several images, including an over-life-size statue of him as Hercules now in Naples, were re-carved with the face of Alexander Severus.[107] SourcesCassius Dio The historian Cassius Dio, who lived from the second half of the second century until sometime after 229, wrote a contemporary account of Elagabalus. Born into a patrician family, Dio spent the greater part of his life in public service. He was a senator under emperor Commodus and governor of Smyrna after the death of Septimius Severus, and then he served as suffect consul around 205, and as proconsul in Africa and Pannonia.[108] Dio's Roman History spans nearly a millennium, from the arrival of Aeneas in Italy until the year 229. His contemporaneous account of Elagabalus's reign is generally considered more reliable than the Augustan History or other accounts for this general time period,[109][110] though by his own admission Dio spent the greater part of the relevant period outside of Rome and had to rely on second-hand information.[108] Furthermore, the political climate in the aftermath of Elagabalus's reign, as well as Dio's own position within the government of Severus Alexander, who held him in high esteem and made him consul again, likely influenced the truth of this part of his history for the worse. Dio regularly refers to Elagabalus as Sardanapalus, partly to distinguish him from his divine namesake,[111] but chiefly to do his part in maintaining the damnatio memoriae and to associate him with another autocrat notorious for a dissolute life.[112] Historian Clare Rowan calls Dio's account a mixture of reliable information and "literary exaggeration", noting that Elagabalus's marriages and time as consul are confirmed by numismatic and epigraphic records.[113] In other instances, Dio's account is inaccurate, such as when he says Elagabalus appointed entirely unqualified officials and that Comazon had no military experience before being named to head the Praetorian Guard,[114] when in fact Comazon had commanded the Third Legion.[52][53] Dio also gives different accounts in different places of when and by whom Diadumenian (whose forces Elagabalus fought) was given imperial names and titles.[115] Martin Icks has written that "It is clear that Dio was not attempting an accurate portrayal of the emperor", an assessment endorsed by Josiah Osgood.[5] Herodian fides exercitus ("the Faith of the Army") Another contemporary of Elagabalus was Herodian, a minor Roman civil servant who lived from c. 170 until 240. His work, History of the Roman Empire since Marcus Aurelius, commonly abbreviated as Roman History, is an eyewitness account of the reign of Commodus until the beginning of the reign of Gordian III. His work largely overlaps with Dio's own Roman History, and the texts, written independently of each other, agree more often than not about Elagabalus and his short but eventful reign.[116] Herodian may have used Dio's work as a source for parts of his account about Elagabalus.[5] Arrizabalaga writes that Herodian is in most ways "less detailed and punctilious than Dio",[117] and he is deemed less reliable by many modern scholars, though Rowan considers his account of Elagabalus's reign more reliable than Dio's[113] and Herodian's lack of literary and scholarly pretensions are considered to make him less biased than senatorial historians.[118] He is considered an important source for the religious reforms which took place during the reign of Elagabalus,[119] which have been confirmed by numismatic[120][121] and archaeological evidence.[122] Augustan HistoryThe source of many stories of Elagabalus's depravity is the Historia Augusta, which includes controversial claims.[123] It is most likely that the Historia Augusta was written towards the end of the fourth century, during the reign of emperor Theodosius I.[124] The account of Elagabalus in the Historia Augusta is of uncertain historical merit.[125] Sections 13 to 17, relating to the fall of Elagabalus, are less controversial among historians.[126] The author of the most scandalous stories in the Historia Augusta concedes that "both these matters and some others which pass belief were, I think, invented by people who wanted to depreciate Heliogabalus to win favour with Alexander".[13] The Historia Augusta is widely regarded to have been written by a single author who used multiple pseudonyms throughout the work, and has been described as a "fantasist" who invented large parts of his historical accounts.[6] Modern historians For readers of the modern age, The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire by Edward Gibbon (1737–1794) further cemented the scandalous reputation of Elagabalus. Gibbon not only accepted and expressed outrage at the allegations of the ancient historians, but he might have added some details of his own; for example, he is the first historian known to claim that Gannys was a eunuch.[127] Gibbon wrote:

The 20th-century anthropologist James George Frazer (author of The Golden Bough) took seriously the monotheistic aspirations of the emperor, but also ridiculed him: "The dainty priest of the Sun [was] the most abandoned reprobate who ever sat upon a throne ... It was the intention of this eminently religious but crack-brained despot to supersede the worship of all the gods, not only at Rome but throughout the world, by the single worship of Elagabalus or the Sun".[129] The first book-length biography was The Amazing Emperor Heliogabalus[130] (1911) by J. Stuart Hay, "a serious and systematic study"[131] more sympathetic than that of previous historians, which nonetheless stressed the exoticism of Elagabalus, calling his reign one of "enormous wealth and excessive prodigality, luxury and aestheticism, carried to their ultimate extreme, and sensuality in all the refinements of its Eastern habit".[132]  Some recent historians paint a more favourable picture of the emperor's rule. Martijn Icks, in Images of Elagabalus (2008; republished as The Crimes of Elagabalus in 2011 and 2012), doubts the reliability of the ancient sources and argues that it was the emperor's unorthodox religious policies that alienated the power elite of Rome, to the point that his grandmother saw fit to eliminate him and replace him with his cousin. He described ancient stories pertaining to the emperor as "part of a long tradition of 'character assassination' in ancient historiography and biography".[133] Leonardo de Arrizabalaga y Prado, in The Emperor Elagabalus: Fact or Fiction? (2008), is also critical of the ancient historians and speculates that neither religion nor sexuality played a role in the fall of the young emperor. Prado instead suggests Elagabalus was the loser in a power struggle within the imperial family, that the loyalty of the Praetorian Guards was up for sale, and that Julia Maesa had the resources to outmaneuver and outbribe her grandson. In this version of events, once Elagabalus, his mother, and his immediate circle had been murdered, a campaign of character assassination began, resulting in a grotesque caricature that has persisted to the present day.[134] Other historians, including Icks, criticized Prado for being overly skeptical of primary sources.[135] Warwick Ball, in his book Rome in the East, writes an apologetic account of the emperor, arguing that descriptions of his religious rites were exaggerated and should be dismissed as propaganda, similar to how pagan descriptions of Christian rites have since been dismissed. Ball describes the emperor's ritual processions as sound political and religious policy, arguing that syncretism of eastern and western deities deserves praise rather than ridicule. Ultimately, he paints Elagabalus as a child forced to become emperor who, as expected of the high-priest of a cult, continued his rituals even after becoming emperor. Ball justified Elagabalus's executions of prominent Roman figures who criticized his religious activities in the same way. Finally, Ball asserts Elagabalus's eventual victory in the sense that his deity would be welcomed by Rome in its Sol Invictus form 50 years later. Ball claims that Sol Invictus came to influence the monotheist Christian beliefs of Constantine, asserting that this influence remains in Christianity to this day.[136] Cultural referencesDespite the attempted damnatio memoriae, stories about Elagabalus survived and figured in many works of art and literature.[137] In Spanish, his name became a word for "glutton", heliogábalo.[137][138] Due to the ancient stories about him, he often appears in literature and other creative media as a decadent figure (becoming something of an anti-hero in the Decadent movement of the late 19th century, and inspiring many famous works of art, especially by Decadents)[89] and the epitome of a young, amoral aesthete. The most notable of these works include:[139] Fiction

Plays

Dance

Music

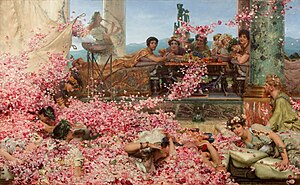

Paintings

Poetry

Television

Severan dynasty family tree

Notes

References

BibliographyPrimary sources

Secondary material

Images

External links

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||