|

Riot Act

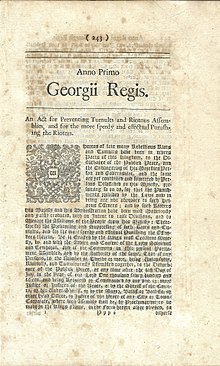

The Riot Act[1] (1 Geo. 1. St. 2. c. 5), sometimes called the Riot Act 1714[2] or the Riot Act 1715,[3] was an act of the Parliament of Great Britain which authorised local authorities to declare any group of 12 or more people to be unlawfully assembled and order them to disperse or face punitive action. The act's full title was "An Act for preventing tumults and riotous assemblies, and for the more speedy and effectual punishing the rioters", and it came into force on 1 August 1715.[4] It was repealed in England and Wales by section 10(2) and Part III of Schedule 3 of the Criminal Law Act 1967. Acts similar to the Riot Act passed into the laws of British colonies in Australia and North America, some of which remain in force today. The phrase "read the riot act" has passed into common usage for a stern reprimand or warning of consequences. Introduction and purposeThe Riot Act 1714 was introduced during a time of civil disturbance in Great Britain, including the Sacheverell riots of 1710, the Coronation riots of 1714 and the 1715 riots in England.[5] The preamble makes reference to "many rebellious riots and tumults [that] have been [taking place of late] in diverse parts of this kingdom", adding that those involved "presum[e] so to do, for that the punishments provided by the laws now in being are not adequate to such heinous offences".[5] Main provisions Proclamation of riotous assemblyThe act created a mechanism for certain local officials to make a proclamation ordering the dispersal of any group of twelve or more people who were "unlawfully, riotously, and tumultuously assembled together". If the group failed to disperse within one hour, then anyone remaining gathered was guilty of a felony without benefit of clergy, punishable by death.[5] The proclamation could be made in an incorporated town or city by the mayor, bailiff or "other head officer", or a justice of the peace. Elsewhere it could be made by a justice of the peace or the sheriff, undersheriff or parish constable. It had to be read out to the gathering concerned and had to follow precise wording detailed in the act; several convictions were overturned because parts of the proclamation had been omitted, in particular "God save the King".[6] The wording that had to be read out to the assembled gathering was as follows:

In a number of jurisdictions, such as Britain, Canada and New Zealand, wording such as this was enshrined and codified in the law itself. While the expression "reading the Riot Act" is cemented in common idiom with its figurative usage, it originated fairly and squarely in statute itself. In New Zealand's Crimes Act 1961, section 88, repealed since 1987, was specifically given the heading of "Reading the Riot Act".[7] Consequences of disregarding the proclamationIf a group of people failed to disperse within one hour of the proclamation, the act provided that the authorities could use force to disperse them. Anyone assisting with the dispersal was specifically indemnified against any legal consequences in the event of any of the crowd being injured or killed.[8][5] Because of the broad authority that the act granted, it was used both for the maintenance of civil order and for political means. A particularly notorious use of the act was the Peterloo Massacre of 1819 in Manchester.[9] Other provisionsThe act also made it a felony punishable by death without benefit of clergy for "any persons unlawfully, riotously and tumultuously assembled together" to cause (or begin to cause) serious damage to places of religious worship, houses, barns, and stables.[5] In the event of buildings being damaged in areas that were not incorporated into a town or city, the residents of the hundred were made liable to pay damages to the property owners concerned. Unlike the rest of the act, this required a civil action. In the case of incorporated areas, the action could be brought against two or more named individuals. This provision encouraged residents to attempt to quell riots in order to avoid paying damages.[10] Prosecutions under the act were restricted to within one year of the event.[5] ControversiesImpracticalityAt times, it was unclear to both rioters and authorities as to whether the reading of the Riot Act had occurred. One example of this is evident in the massacre of St George's Fields of 1768. At the trials following the incident, there was confusion among witnesses as to when the Riot Act had actually been read.[11] Use of forceIn the 1768 massacre of St George's Fields, large numbers of subjects gathered outside King's Bench Prison in Southwark, south London, to protest against the incarceration of John Wilkes. Officials feared that the crowd would forcibly release Wilkes, and troops arrived to guard the prison. After some time, as well as provocation by the rioters, the troops opened fire on the crowd. There were several fatalities, including non-participants of the riot who were struck by stray bullets.[12] Some scholars believe that this massacre set the legal precedent for the justified use of force in future riots.[11] The provision pertaining to the use of force can be found in section 3 of the Riot Act:

There was also confusion regarding the use of troops as it pertained to the one-hour mark. Rioters often believed that the military could not use force until one hour had passed since the reading of the proclamation. This is evident in the actions of the rioters at the massacre of St George's Fields, particularly their provocative behaviour towards the soldiers.[13] Subsequent history of the Riot Act in the UK and coloniesThe Riot Act caused confusion during the Gordon Riots of 1780, when the authorities felt uncertain of their power to take action to stop the riots without a reading of the Riot Act. After the riots, Lord Mansfield observed that the Riot Act did not take away the pre-existing power of the authorities to use force to stop a violent riot; it only created the additional offence of failing to disperse after a reading of the Riot Act.[8] The Riot Act was read prior to the Peterloo Massacre of 1819 and the Cinderloo Uprising of 1821, as well as before the Bristol Riots at Queen's Square in 1831.[14][15] Both are held to be related to the Unreformed House of Commons, which was righted in the Reform Act 1832. Lieutenant-Governor Sir Francis Bond Head and his administrators read the act during the Upper Canada Rebellion of 1837.[16] The death penalty created by sections one, four and five of the act was reduced to transportation for life by section one of the Punishment of Offences Act 1837.[17] The Riot Act eventually drifted into disuse. The last time it was definitely read in England was in Birkenhead, Cheshire, on 3 August 1919, during the second police strike, when large numbers of police officers from Birkenhead, Liverpool and Bootle joined the strike. Troops were called in to deal with the rioting and looting that had begun, and a magistrate read out the Riot Act. None of the rioters subsequently faced the charge of a statutory felony.[citation needed] Earlier in the same year, at the battle of George Square on 31 January, in Glasgow, the city's sheriff was in the process of reading the Riot Act to a crowd of 20,000–25,000 when the sheet of paper he was reading from was ripped out of his hands by one of the rioters. The last time it was read in Scotland was by the deputy town clerk James Gildea in Airdrie in 1971.[citation needed] The act was repealed on 18 July 1973 for the United Kingdom by the Statute Law (Repeals) Act 1973.[18] In other countriesThe Riot Act passed into the law of those countries that were then colonies of Great Britain, including the North American colonies that would become the United States and Canada.[19][20] In many common-law jurisdictions, a lesser disturbance such as an affray or an unruly gathering may be deemed an unlawful assembly by the local authorities and ordered to disperse. Failure to obey such an order would typically be prosecuted as a summary offence. AustraliaActs similar to the Riot Act have been enacted in some Australian states. For example, in Victoria the Unlawful Assemblies and Processions Act 1958 allowed a magistrate to disperse a crowd with the words (or words to the effect of):

Anyone remaining after 15 minutes may be charged and imprisoned for one month (first offence) or three months (repeat offence). The act does not apply to crowds gathered for the purpose of an election. The same act allows a magistrate to appoint citizens as "special [police] constables" to disperse a crowd and provides indemnity for the hurting or killing of unlawfully assembled people in an attempt to disperse them.[21] The Act was significantly amended in 2007.[21] BelizeBelize, another former British colony, also still retains the principle of the Riot Act; it was last read on 21 January 2005, during the 2005 Belize unrest. While there is no specific form of words provided for such proclamations, they must be made "in the King's name". The provisions are formed in sections 231, 246 and 247 of the country's criminal code, providing particularly that:

Any person who does not disperse within one hour of the proclamation being read is liable to receive a maximum penalty of five years imprisonment.[22] CanadaIn Canada, the Riot Act has been incorporated in a modified form into the Criminal Code, a federal statute. Sections 32 and 33 of the Code deal with the power of police officers to suppress riots.[23][24] The Code defines a riot as an "unlawful assembly" that has "begun to disturb the peace tumultuously".[25] When twelve or more persons are "unlawfully and riotously assembled together", the proclamation can be read by a number of public officials, such as justices of the peace, provincial court judges, mayors, and sheriffs.[26] The proclamation can also be read during prison riots: Quebec and Manitoba have designated senior correctional staff as justices of the peace for the purpose of reading the proclamation, while other provinces will ask a local justice of the peace to travel to the prison to read the proclamation.[27] The proclamation is worded as follows:

Unlike the original Riot Act, the Criminal Code requires the assembled people to disperse within thirty minutes.[28] When the proclamation has not been read, the punishment for rioting is up to two years of imprisonment.[29] When the proclamation has been read and then ignored, the penalty increases, up to life imprisonment.[28] The maximum penalty of life imprisonment also applies to someone who wilfully uses force to hinder the reading of the proclamation, or to those fail to disperse and who have reasonable grounds to believe the proclamation would have been made had the official not been hindered by force. The proclamation was read during the Winnipeg general strike of 1919[30] and the 1958 riot over racial discrimination against First Nations in Prince Rupert, British Columbia.[31][32] One recent reading was during Vancouver's Stanley Cup riot in June 2011.[33] Despite the reading of the proclamation, rioters were almost always charged under s 65 due to the difficulty of proving the elements of the offence in s 68. Many rioters also faced charges related to assaulting peace officers, mischief, theft, arson and assault. Caribbean regionIn St Kitts on 29 January 1935 the act was read at Buckley's Estate[34] located on the western outskirts of Basseterre during the "Sugar Workers Rebellion" [35] In St Vincent on 21 October the act was read in Kingstown during "The Labour Rebellion" [35] New ZealandIn New Zealand the Riot Act was incorporated into sections 87 and 88 of the Crimes Act 1961.[36] The proclamation is worded as follows:

The need to read the Riot Act was removed by section three of the Crimes Amendment Act (1987 No 1).[38][39] United StatesA riot act was passed by the Massachusetts state legislature in 1786 during Shays' Rebellion.[40] At the federal level, the principle of the Riot Act was incorporated into the first Militia Act (1 Stat. 264) of 2 May 1792. The act's long title was "An act to provide for calling forth the militia to execute the laws of the Union, suppress insurrections and repel invasions". Section 3 of the Militia Act gave power to the president to issue a proclamation to "command the insurgents to disperse, and retire peaceably to their respective abodes, within a limited time", and authorized him to use the militia if they failed to do so. Substantively identical language is currently codified in title 10 of the United States Code, Chapter 13, Section 254.[41] Prohibitions against inciting riots were further codified in United States federal law under 18 U.S. Code § 2101 – Riots, as part of the Civil Rights Act of 1968, passed by the United States Congress.[42][43] "Read the Riot Act"Because the authorities were required to read the proclamation that referred to the Riot Act before they could enforce it, the expression "to read the Riot Act" entered into common language as a phrase meaning "to reprimand severely", with the added sense of a stern warning.[44] See also

References

External links

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Portal di Ensiklopedia Dunia