|

Quantum triviality

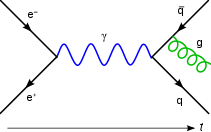

In a quantum field theory, charge screening can restrict the value of the observable "renormalized" charge of a classical theory. If the only resulting value of the renormalized charge is zero, the theory is said to be "trivial" or noninteracting. Thus, surprisingly, a classical theory that appears to describe interacting particles can, when realized as a quantum field theory, become a "trivial" theory of noninteracting free particles. This phenomenon is referred to as quantum triviality. Strong evidence supports the idea that a field theory involving only a scalar Higgs boson is trivial in four spacetime dimensions,[1][2] but the situation for realistic models including other particles in addition to the Higgs boson is not known in general. Nevertheless, because the Higgs boson plays a central role in the Standard Model of particle physics, the question of triviality in Higgs models is of great importance. This Higgs triviality is similar to the Landau pole problem in quantum electrodynamics, where this quantum theory may be inconsistent at very high momentum scales unless the renormalized charge is set to zero, i.e., unless the field theory has no interactions. The Landau pole question is generally considered to be of minor academic interest for quantum electrodynamics because of the inaccessibly large momentum scale at which the inconsistency appears. This is not however the case in theories that involve the elementary scalar Higgs boson, as the momentum scale at which a "trivial" theory exhibits inconsistencies may be accessible to present experimental efforts such as at the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) at CERN. In these Higgs theories, the interactions of the Higgs particle with itself are posited to generate the masses of the W and Z bosons, as well as lepton masses like those of the electron and muon. If realistic models of particle physics such as the Standard Model suffer from triviality issues, the idea of an elementary scalar Higgs particle may have to be modified or abandoned. The situation becomes more complex in theories that involve other particles however. In fact, the addition of other particles can turn a trivial theory into a nontrivial one, at the cost of introducing constraints. Depending on the details of the theory, the Higgs mass can be bounded or even calculable.[2] These quantum triviality constraints are in sharp contrast to the picture one derives at the classical level, where the Higgs mass is a free parameter. Quantum triviality can also lead to a calculable Higgs mass in asymptotic safety scenarios.[2] Triviality and the renormalization group

Modern considerations of triviality are usually formulated in terms of the real-space renormalization group, largely developed by Kenneth Wilson and others. Investigations of triviality are usually performed in the context of lattice gauge theory. A deeper understanding of the physical meaning and generalization of the renormalization process, which goes beyond the dilatation group of conventional renormalizable theories, came from condensed matter physics. Leo P. Kadanoff's paper in 1966 proposed the "block-spin" renormalization group.[3] The blocking idea is a way to define the components of the theory at large distances as aggregates of components at shorter distances. This approach covered the conceptual point and was given full computational substance[4] in Wilson's extensive important contributions. The power of Wilson's ideas was demonstrated by a constructive iterative renormalization solution of a long-standing problem, the Kondo problem, in 1974, as well as the preceding seminal developments of his new method in the theory of second-order phase transitions and critical phenomena in 1971[citation needed]. He was awarded the Nobel prize for these decisive contributions in 1982. In more technical terms, let us assume that we have a theory described by a certain function of the state variables and a certain set of coupling constants . This function may be a partition function, an action, a Hamiltonian, etc. It must contain the whole description of the physics of the system. Now we consider a certain blocking transformation of the state variables , the number of must be lower than the number of . Now let us try to rewrite the function only in terms of the . If this is achievable by a certain change in the parameters, , then the theory is said to be renormalizable. The most important information in the RG flow are its fixed points. The possible macroscopic states of the system, at a large scale, are given by this set of fixed points. If these fixed points correspond to a free field theory, the theory is said to be trivial. Numerous fixed points appear in the study of lattice Higgs theories, but the nature of the quantum field theories associated with these remains an open question.[2] Historical backgroundThe first evidence of possible triviality of quantum field theories was obtained by Landau, Abrikosov, and Khalatnikov[5][6][7] by finding the following relation of the observable charge gobs with the "bare" charge g0,

where m is the mass of the particle, and Λ is the momentum cut-off. If g0 is finite, then gobs tends to zero in the limit of infinite cut-off Λ. In fact, the proper interpretation of Eq.1 consists in its inversion, so that g0 (related to the length scale 1/Λ) is chosen to give a correct value of gobs,

The growth of g0 with Λ invalidates Eqs. (1) and (2) in the region g0 ≈ 1 (since they were obtained for g0 ≪ 1) and the existence of the "Landau pole" in Eq.2 has no physical meaning. The actual behavior of the charge g(μ) as a function of the momentum scale μ is determined by the full Gell-Mann–Low equation

which gives Eqs.(1),(2) if it is integrated under conditions g(μ) = gobs for μ = m and g(μ) = g0 for μ = Λ, when only the term with is retained in the right hand side. The general behavior of relies on the appearance of the function β(g). According to the classification by Bogoliubov and Shirkov,[8] there are three qualitatively different situations:

The latter case corresponds to the quantum triviality in the full theory (beyond its perturbation context), as can be seen by reductio ad absurdum. Indeed, if gobs is finite, the theory is internally inconsistent. The only way to avoid it, is to tend to infinity, which is possible only for gobs → 0. ConclusionsAs a result, the question of whether the Standard Model of particle physics is nontrivial remains a serious unresolved question. Theoretical proofs of triviality of the pure scalar field theory exist, but the situation for the full standard model is unknown. The implied constraints on the standard model have been discussed.[9][10][11] [12][13][14] See alsoReferences

|