|

Pioneer 10

Pioneer 10 (originally designated Pioneer F) is a NASA space probe launched in 1972 that completed the first mission to the planet Jupiter.[6] Pioneer 10 became the first of five planetary probes and 11 artificial objects to achieve the escape velocity needed to leave the Solar System. This space exploration project was conducted by the NASA Ames Research Center in California. The space probe was manufactured by TRW Inc. Pioneer 10 was assembled around a hexagonal bus with a 2.74-meter (9 ft 0 in) diameter parabolic dish high-gain antenna, and the spacecraft was spin stabilized around the axis of the antenna. Its electric power was supplied by four radioisotope thermoelectric generators that provided a combined 155 watts at launch. It was launched on March 3, 1972, at 01:49:00 UTC (March 2 local time), by an Atlas-Centaur rocket from Cape Canaveral, Florida. Between July 15, 1972, and February 15, 1973, it became the first spacecraft to traverse the asteroid belt. Photography of Jupiter began on November 6, 1973, at a range of 25 million kilometers (16 million miles), and about 500 images were transmitted. The closest approach to the planet was on December 3, 1973, at a range of 132,252 kilometers (82,178 mi). During the mission, the on-board instruments were used to study the asteroid belt, the environment around Jupiter, the solar wind, cosmic rays, and eventually the far reaches of the Solar System and heliosphere.[6] Radio communications were lost with Pioneer 10 on January 23, 2003, because of the loss of electric power for its radio transmitter, with the probe at a distance of 12 billion km (80 AU; 7.5 billion mi) from Earth. Mission backgroundHistoryIn the 1960s, American aerospace engineer Gary Flandro of the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory conceived of a mission, known as the Planetary Grand Tour, that would exploit a rare alignment of the outer planets of the Solar System. This mission would ultimately be accomplished in the late 1970s by the two Voyager probes, but in order to prepare for it, NASA decided in 1964 to experiment with launching a pair of probes to the outer Solar System.[7] An advocacy group named the Outer Space Panel and chaired by American space scientist James A. Van Allen, worked out the scientific rationale for exploring the outer planets.[8][9] NASA Goddard Spaceflight Center put together a proposal for a pair of "Galactic Jupiter Probes" that would pass through the asteroid belt and visit Jupiter. These were to be launched in 1972 and 1973 during favorable windows that occurred only a few weeks every 13 months. Launch during other time intervals would have been more costly in terms of propellant requirements.[10] Approved by NASA in February 1969,[10] the twin spacecraft were designated Pioneer F and Pioneer G before launch; later, they were named Pioneer 10 and Pioneer 11 respectively. They formed part of the Pioneer program,[11] a series of United States uncrewed space missions launched between 1958 and 1978. This model was the first in the series to be designed for exploring the outer Solar System. Based on proposals issued throughout the 1960s, the early mission objectives were to explore the interplanetary medium past the orbit of Mars, study the asteroid belt and assess the possible hazard to spacecraft traveling through the belt, and explore Jupiter and its environment.[6] Later development-stage objectives included the probe closely approaching Jupiter to provide data on the effect the environmental radiation surrounding Jupiter would have on the spacecraft instruments. More than 150 scientific experiments were proposed for the missions.[12] The experiments to be carried on the spacecraft were selected in a series of planning sessions during the 1960s, then were finalized by early 1970. These would be to perform imaging and polarimetry of Jupiter and several of its satellites, make infrared and ultraviolet observations of Jupiter, detect asteroids and meteoroids, determine the composition of charged particles, and to measure magnetic fields, plasma, cosmic rays and the zodiacal light.[6] Observation of the spacecraft communications as it passed behind Jupiter would allow measurements of the planetary atmosphere, while tracking data would improve estimates of the mass of Jupiter and its moons.[6] NASA Ames Research Center, rather than Goddard, was selected to manage the project as part of the Pioneer program.[10] The Ames Research Center, under the direction of Charles F. Hall, was chosen because of its previous experience with spin-stabilized spacecraft. The requirements called for a small, lightweight spacecraft which was magnetically clean and which could perform an interplanetary mission. It was to use spacecraft modules that had already been proven in the Pioneer 6 through 9 missions.[6] Ames commissioned a documentary film by George Van Valkenburg titled Jupiter Odyssey. It received numerous international awards, and is visible on Van Valkenburg's YouTube channel. In February 1970, Ames awarded a combined US$380 million contract to TRW Inc. for building both of the Pioneer 10 and 11 vehicles, bypassing the usual bidding process to save time. B. J. O'Brien and Herb Lassen led the TRW team that assembled the spacecraft.[13] Design and construction of the spacecraft required an estimated 25 million man-hours.[14] An engineer from TRW quipped, "This spacecraft is guaranteed for two years of interplanetary flight. If any component fails within that warranty period, just return the spacecraft to our shop and we will repair it free of charge."[15] To meet the schedule, the first launch would need to take place between February 29 and March 17 so that it could arrive at Jupiter in November 1974. This was later revised to an arrival date of December 1973 in order to avoid conflicts with other missions over the use of the Deep Space Network for communications, and to miss the period when Earth and Jupiter would be at opposite sides of the Sun. The encounter trajectory for Pioneer 10 was selected to maximize the information returned about the radiation environment around Jupiter, even if this caused damage to some systems. It would come within about three times the radius of the planet, which was thought to be the closest it could approach and still survive the radiation. The trajectory chosen would give the spacecraft a good view of the sunlit side.[16]

Spacecraft designThe Pioneer 10 bus measures 36 centimeters (14 in) deep and with six 76-centimeter (30 in) long panels forming the hexagonal structure. The bus houses propellant to control the orientation of the probe and eight of the eleven scientific instruments. The equipment compartment lay within an aluminum honeycomb structure to provide protection from meteoroids. A layer of insulation, consisting of aluminized mylar and kapton blankets, provides passive thermal control. Heat was generated by the dissipation of 70 to 120 watts (W) from the electrical components inside the compartment. The heat range was maintained within the operating limits of the equipment by means of louvers located below the mounting platform.[3] The spacecraft had a launch mass of about 260 kilograms (570 lb).[6]: 42 At launch, the spacecraft carried 36 kilograms (79 lb) of liquid hydrazine monopropellant in a 42-centimeter (17 in) diameter spherical tank.[3] Orientation of the spacecraft is maintained with six 4.5 N,[17] hydrazine thrusters mounted in three pairs. Pair one maintained a constant spin-rate of 4.8 rpm, pair two controlled the forward thrust, and pair three controlled the attitude. The attitude pair were used in conical scanning maneuvers to track Earth in its orbit.[18] Orientation information was also provided by a star sensor able to reference Canopus, and two Sun sensors.[19] Power and communications Pioneer 10 uses four SNAP-19 radioisotope thermoelectric generators (RTGs). They are positioned on two three-rod trusses, each 3 meters (9.8 ft) in length and 120 degrees apart. This was expected to be a safe distance from the sensitive scientific experiments carried on board. Combined, the RTGs provided 155 W at launch, and decayed to 140 W in transit to Jupiter. The spacecraft required 100 W to power all systems.[6]: 44–45 The generators are powered by the radioisotope fuel plutonium-238, which is housed in a multi-layer capsule protected by a graphite heat shield.[20] The pre-launch requirement for the SNAP-19 was to provide power for two years in space; this was greatly exceeded during the mission.[21] The plutonium-238 has a half-life of 87.74 years, so that after 29 years the radiation being generated by the RTGs was at 80% of its intensity at launch. However, steady deterioration of the thermocouple junctions led to a more rapid decay in electrical power generation, and by 2001 the total power output was 65 W. As a result, later in the mission only selected instruments could be operated at any one time.[3] The space probe includes a redundant system of transceivers, one attached to the narrow-beam, high-gain antenna, the other to an omni-antenna and medium-gain antenna. The parabolic dish for the high-gain antenna is 2.74 meters (9.0 ft) in diameter and made from an aluminum honeycomb sandwich material. The spacecraft was spun about an axis that is parallel to the axis of this antenna so that it could remain oriented toward the Earth.[3] Each transceiver is an 8 W one and transmits data across the S-band using 2110 MHz for the uplink from Earth and 2292 MHz for the downlink to Earth with the Deep Space Network tracking the signal. Data to be transmitted is passed through a convolutional encoder so that most communication errors could be corrected by the receiving equipment on Earth.[6]: 43 The data transmission rate at launch was 256 bit/s, with the rate degrading by about 1.27 millibit/s for each day during the mission.[3] Much of the computation for the mission is performed on Earth and transmitted to the spacecraft, where it was able to retain in memory up to five commands of the 222 possible entries by ground controllers. The spacecraft includes two command decoders and a command distribution unit, a very limited form of a processor, to direct operations on the spacecraft. This system requires that mission operators prepare commands long in advance of transmitting them to the probe. A data storage unit is included to record up to 6,144 bytes of information gathered by the instruments. The digital telemetry unit is used to prepare the collected data in one of the thirteen possible formats before transmitting it back to Earth.[6]: 38 Scientific instruments

Mission profileLaunch and trajectory Pioneer 10 was launched on March 3, 1972, at 01:49:00 UTC (8:49 p.m. Eastern Standard Time on March 2) by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration from Space Launch Complex 36A in Florida, aboard an Atlas-Centaur. The third stage of the expendable vehicle consisted of a solid fuel Star-37E stage (TE-M-364-4) developed specifically for the Pioneer missions. This stage provided about 15,000 pounds (6,800 kg) of thrust and spun up the spacecraft.[34] The spacecraft had an initial spin rate of 30 rpm. Twenty minutes following the launch, the vehicle's three booms were extended, which slowed the rotation rate to 4.8 rpm. This rate was maintained throughout the voyage. The launch vehicle accelerated the probe for a net interval of 17 minutes, reaching a velocity of 51,682 km/h (32,114 mph).[35] After the high-gain antenna was contacted, several of the instruments were activated for testing while the spacecraft was moving through the Earth's radiation belts. Ninety minutes after launch, the spacecraft reached interplanetary space.[35] Pioneer 10 passed by the Moon in 11 hours[36] and became the fastest human-made object at that time.[37] Two days after launch, the scientific instruments were turned on, beginning with the cosmic ray telescope. After ten days, all of the instruments were active.[36] During the first seven months of the journey, the spacecraft made three course corrections. The on-board instruments underwent checkouts, with the photometers examining Jupiter and the Zodiacal light, and experiment packages being used to measure cosmic rays, magnetic fields and the solar wind. The only anomaly during this interval was the failure of the Canopus sensor, which instead required the spacecraft to maintain its orientation using the two Sun sensors.[35] While passing through interplanetary medium, Pioneer 10 became the first mission to detect interplanetary atoms of helium. It also observed high-energy ions of aluminum and sodium in the solar wind. The spacecraft recorded important heliophysics data in early August 1972 by registering a solar shock wave when it was at a distance of 2.2 AU (330 million km; 200 million mi).[38] On July 15, 1972, Pioneer 10 was the first spacecraft to enter the asteroid belt,[4] located between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter. The project planners expected a safe passage through the belt, and the closest the trajectory would take the spacecraft to any of the known asteroids was 8.8 million kilometers (5.5 million miles). One of the nearest approaches was to the asteroid 307 Nike on December 2, 1972.[39] The on-board experiments demonstrated a deficiency of particles below a micrometer (μm) in the belt, as compared to the vicinity of the Earth. The density of dust particles between 10 and 100 μm did not vary significantly during the trip from the Earth to the outer edge of the belt. Only for particles with a diameter of 100 μm to 1.0 mm did the density show an increase, by a factor of three in the region of the belt. No fragments larger than a millimeter were observed in the belt, indicating these are likely rare; certainly much less common than anticipated. As the spacecraft did not collide with any particles of substantial size, it passed safely through the belt, emerging on the other side about February 15, 1973.[40][41]

Encounter with JupiterOn November 6, 1973, the Pioneer 10 spacecraft was at a distance of 25 million km (16 million mi) from Jupiter. Testing of the imaging system began, and the data were successfully received back at the Deep Space Network. A series of 16,000 commands were then uploaded to the spacecraft to control the flyby operations during the next sixty days. The orbit of the outer moon Sinope was crossed on November 8. The bow shock of Jupiter's magnetosphere was reached on November 16, as indicated by a drop in the velocity of the solar wind from 451 km/s (280 mi/s) to 225 km/s (140 mi/s). The magnetopause was passed through a day later. The spacecraft instruments confirmed that the magnetic field of Jupiter was inverted compared to that of Earth. By the 29th, the orbits of all of the outermost moons had been passed, and the spacecraft was operating flawlessly.[42] Red and blue pictures of Jupiter were being generated by the imaging photopolarimeter as the rotation of the spacecraft carried the instrument's field of view past the planet. These red and blue colors were combined to produce a synthetic green image, allowing a three-color combination to produce the rendered image. On November 26, a total of twelve such images were received back on Earth. By December 2, the image quality exceeded the best images made from Earth. These were being displayed in real-time back on Earth, and the Pioneer program would later receive an Emmy award for this presentation to the media. The motion of the spacecraft produced geometric distortions that later had to be corrected by computer processing.[42] During the encounter, a total of more than 500 images were transmitted.[43] The trajectory of the spacecraft took it along the magnetic equator of Jupiter, where the ion radiation was concentrated.[44] Peak flux for this electron radiation is 10,000 times stronger than the maximum radiation around the Earth.[45] Pioneer 10 passed through the inner radiation belts within 20 RJ, receiving an integrated dose of 200,000 rads from electrons and 56,000 rads from protons (in comparison, a whole body dose of 500 rads is fatal to humans).[46] The level of radiation at Jupiter was ten times more powerful than Pioneer's designers had predicted, leading to fears that the probe would not survive. Starting on December 3, the radiation around Jupiter caused false commands to be generated. Most of these were corrected by contingency commands, but an image of Io and a few close-ups of Jupiter were lost. Similar false commands would be generated on the way out from the planet.[42] Nonetheless, Pioneer 10 did succeed in obtaining images of the moons Ganymede and Europa. The image of Ganymede showed low albedo features in the center and near the south pole, while the north pole appeared brighter. Europa was too far away to obtain a detailed image, although some albedo features were apparent.[47] The trajectory of Pioneer 10 was chosen to take it behind Io, allowing the refractive effect of the moon's atmosphere on the radio transmissions to be measured. This demonstrated that the ionosphere of the moon was about 700 kilometers (430 mi) above the surface of the day side, and the density ranged from 60,000 electrons per cubic centimeter on the dayside to 9,000 electrons per cubic centimeter on the night face. An unexpected discovery was that Io was orbiting within a cloud of hydrogen that extended for about 805,000 kilometers (500,000 mi), with a width and height of 402,000 kilometers (250,000 mi). A smaller, 110,000-kilometer (68,000 mi) cloud was believed to have been detected near Europa.[47] It was not until after Pioneer 10 had cleared the asteroid belt that NASA selected a trajectory towards Jupiter which included a slingshot effect to send the spacecraft out of the Solar System. Pioneer 10 was the first spacecraft to attempt such a maneuver, a model for future missions. Such an extended mission was not in the initial proposal, but was planned for prior to launch.[48] At the closest approach, the velocity of the spacecraft reached 132,000 km/h (82,000 mph; 37,000 m/s),[49] and it came within 132,252 kilometers (82,178 mi) of the outer atmosphere of Jupiter. Close-up images of the Great Red Spot and the terminator were obtained. Communication with the spacecraft then ceased as it passed behind the planet.[44] The radio occultation data allowed the temperature structure of the outer atmosphere to be measured, showing a temperature inversion between the altitudes with 10 and 100 mbar pressures. Temperatures at the 10-mbar level ranged from −133 to −113 °C (140 to 160 K; −207 to −171 °F), while temperatures at the 100 mbar level were −183 to −163 °C (90.1 to 110.1 K; −297.4 to −261.4 °F).[50] The spacecraft generated an infrared map of the planet, which confirmed the idea that the planet radiated more heat than it received from the Sun.[51] Crescent images of the planet were then returned as Pioneer 10 moved away from the planet.[52] As the spacecraft headed outward, it again passed the bow shock of Jupiter's magnetosphere. As this front is constantly shifting in space because of dynamic interaction with the solar wind, the vehicle crossed the bow shock a total of 17 times before it escaped completely.[53]

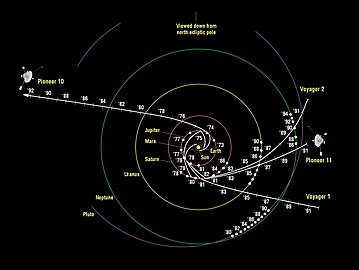

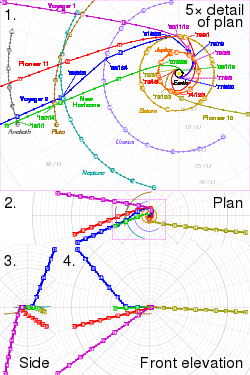

Deep spacePioneer 10 crossed the orbit of Saturn in 1976 and the orbit of Uranus in 1979.[54] On June 13, 1983, the craft crossed the orbit of Neptune, and so became the first human-made object to leave the proximity of the major planets of the Solar System. The mission came to an official end on March 31, 1997, when it had reached a distance of 67 AU (10.0 billion km; 6.2 billion mi) from the Sun, though the spacecraft was still able to transmit coherent data after this date.[3] After March 31, 1997, Pioneer 10's weak signal continued to be tracked by the Deep Space Network to aid the training of flight controllers in the process of acquiring deep-space radio signals. There was an Advanced Concepts study applying chaos theory to extract coherent data from the fading signal.[55] The last successful reception of telemetry was received from Pioneer 10 on April 27, 2002; subsequent signals were barely strong enough to detect and provided no usable data. The final, very weak signal from Pioneer 10 was received on January 23, 2003, when it was 12 billion km (80 AU; 7.5 billion mi) from Earth.[56] Further attempts to contact the spacecraft were unsuccessful. A final attempt was made on the evening of March 4, 2006, the last time the antenna would be correctly aligned with Earth. No response was received from Pioneer 10.[57] NASA decided that the RTG units had probably fallen below the power threshold needed to operate the transmitter. Hence, no further attempts at contact were made.[58] Timeline  Plot 1 is viewed from the north ecliptic pole, to scale. Plots 2 to 4 are third-angle projections at 20% scale. In the SVG file, hover over a trajectory or orbit to highlight it and its associated launches and flybys.

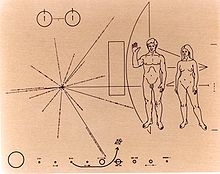

Current status and future On July 18, 2023, Voyager 2 overtook Pioneer 10, making Pioneer 10 the third farthest spacecraft from the Sun after Voyager 1 and Voyager 2.[63][64] As of June 2024, the probe is estimated to be 137.3 AU (20.5 billion km; 12.8 billion mi) from Earth and 136.3 AU (20.4 billion km; 12.7 billion mi) from the Sun.[65] Sunlight takes 18.9 hours to reach Pioneer 10. The brightness of the Sun from the spacecraft is magnitude −16.0.[65] Pioneer 10 is currently travelling in the direction of the constellation Taurus.[65] If left undisturbed, Pioneer 10 and its sister craft Pioneer 11 will join the two Voyager spacecraft and the New Horizons spacecraft in leaving the Solar System to wander the interstellar medium. The Pioneer 10 trajectory is expected to take it in the general direction of the star Aldebaran, currently located at a distance of about 68 light years. If Aldebaran had zero relative velocity, it would require more than two million years for the spacecraft to reach it.[3][65] Well before that, in about 90,000 years, Pioneer 10 will pass about 0.23 parsecs (0.75 light-years) from the late K-type star HIP 117795.[66] This is the closest stellar flyby in the next few million years of all the Pioneer, Voyager, and New Horizons spacecraft, which are leaving the Solar System. A backup unit, Pioneer H, is currently on display in the "Milestones of Flight" gallery at the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C.[67] Many elements of the mission proved to be critical in the planning of the Voyager program.[68] Pioneer plaque Because it was strongly advocated by Carl Sagan,[13] Pioneer 10 and Pioneer 11 carry a 152 by 229 mm (6.0 by 9.0 in) gold-anodized aluminum plaque in case either spacecraft is ever found by intelligent life-forms from another planetary system. The plaques feature the nude figures of a human male and female along with several symbols that are designed to provide information about the origin of the spacecraft.[69] The plaque is attached to the antenna support struts where it would be shielded from interstellar dust.[70] Pioneer 10 in popular mediaIn the film Star Trek V: The Final Frontier, a Klingon Bird-of-Prey destroys Pioneer 10 as target practice.[71] In the serialized speculative fiction multimedia narrative 17776, one of the main characters is a sentient Pioneer 10. See alsoWikimedia Commons has media related to Pioneer 10.

References

Bibliography

External links

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||