|

Number (sports)

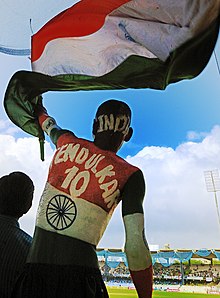

In team sports, the number, often referred to as the uniform number, squad number, jersey number, shirt number, sweater number, or similar (with such naming differences varying by sport and region) is the number worn on a player's uniform, to identify and distinguish each player (and sometimes others, such as coaches and officials) from others wearing the same or similar uniforms. The number is typically displayed on the rear of the jersey, often accompanied by the surname. Sometimes it is also displayed on the front and/or sleeves, or on the player's shorts or headgear. It is used to identify the player to officials, other players, official scorers, and spectators; in some sports, it is also indicative of the player's position. The first use of jersey numbers is credited to a football team from New Zealand called the Nelson Football Club, who began wearing numbered jerseys in 1911. The numbers were used to help the spectators identify the players on the field, as well as to help the referee keep track of fouls and other infractions. The International Federation of Football History and Statistics, an organization of association football historians, traces the origin of numbers to a 1911 association football match in Sydney,[1] although photographic evidence exists of numbers being used in Australia as early as May 1903 in a Fitzroy v Collingwood Australian rules football match.[2] Player numbers were used in a Queensland vs. New Zealand rugby match played on 17 July 1897, in Brisbane, Australia, as reported in the Brisbane Courier.[3] Association football In association football, the first record of numbered jerseys date back to 1911, with Australian teams Sydney Leichhardt and HMS Powerful being the first to use squad numbers on their backs.[4] One year later, numbering in football was mandated in New South Wales.[5] In South America, Argentina was the first country with numbered shirts. It was during the Scottish team Third Lanark's tour to South America of 1923, they played a friendly match vs. a local combined team ("Zona Norte") on 10 June. Both squads were numbered from 1–11.[6] North America saw its first football match with squad numbers on 30 March 1924, when St. Louis Vesper Buick and Fall River F.C. (winners of St. Louis and American soccer leagues, respectively) played the National Challenge Cup, although only the local team wore numbered shirts.[7]  In England, Arsenal coach Herbert Chapman brought the idea of numbered shirts,[8] worn for the first time when his team played Sheffield Wednesday in 1928. Arsenal wore shirts from 1 to 11 while their rivals' numbered from 12 to 22.[9][10] Similar numbering criteria were used in the 1933 FA Cup Final between Everton and Manchester City.[11] Nevertheless, it was not until the 1939–40 season when the Football League ruled that squads had to wear numbers for each player.[11][7] Numbers were traditionally assigned based on a player's position or reputation on the field, with the starting 11 players wearing 1 to 11, and the substitutes wearing bigger numbers. The goalkeeper would generally wear number 1, then defenders, midfield players and forwards in ascending order.[12] The 1950 FIFA World Cup was the first FIFA competition to see squad numbers for each players,[9][13] but persistent numbers would not be issued until the 1954 World Cup, where each man in a country's 22-man squad wore a specific number from 1 to 22 for the duration of the tournament. After some teams such as Argentina fielded non-goalkeeper players with number 1 (in the 1982 and 1986 World Cups), FIFA ruled that number 1 had to be assigned to a goalkeeper exclusively. That change was first applied in the 1990 World Cup.[14][15] The rule is still active for competitions organised by the body.[16] In 1993, England's Football Association switched to persistent squad numbers, abandoning the mandatory use of 1–11 for the starting line-up. The persistent number system became standard in the FA Premier League in the 1993–94 season, with names printed above the numbers. Most European top leagues adopted the system over the next five years.[7] In addition to "1" being commonly assigned to the starting goalkeeper, it is also common for defenders to wear numbers in the lower single digits, for strikers to wear "7" or "9" or "11", and for a team's central playmaker to wear "10".[6][17] It is common for players to change numbers within a club as their career progresses. For example, Cesc Fàbregas was first assigned the number 57 on arrival at Arsenal in 2003. On promotion to the first team squad he was switched to number 15 before inheriting his preferred number 4 following the departure of Patrick Vieira. Very big numbers, the most common being 88, are often reserved and used as placeholders, when a new player has been signed and played by the manager prior to having a formal squad number. However, in some countries these high numbers are well-used, in some cases because the player's preferred number is already taken or for other reasons. On joining A.C. Milan, Andriy Shevchenko, Ronaldinho and Mathieu Flamini all wore numbers reflecting the year of their birth (76, 80 and 84 respectively), because their preferred numbers were already being worn. Australian rules football Squad numbers first appeared on Australian rules football guernseys when clubs travelled interstate.[18] Players traditionally wear numbers on the backs of their guernseys, although in some competitions, such as the WAFL, may feature teams who wear smaller numbers on the front, usually on one side of the chest. The number being worn is not relevant to the player's position on the ground, although some clubs will allocate a prestigious number to the team captain - examples include Port Adelaide, who assign number 1, and Richmond, who traditionally allocate number 17 in honour of former captain Jack Dyer. In these situations, it is customary for players who relinquish the captaincy to switch to another number. AFL clubs generally do not retire numbers, and instead make a ceremony of continuity, featuring retiring champions "passing on" their famous guernsey numbers to chosen successors, usually at a club function or press conference.[19] Prestigious numbers are handed on to highly touted draftees or young up-and-coming players who are shown to have promise and may share certain traits with the previous wearer, such as position or playing style. For example, as of 2010, Michael Hurley inherited the number 18 jumper left vacant by the retired Matthew Lloyd, effectively keeping the number 18 in Essendon's goal-square for another era. Retired numbers include Collingwood's number 42, worn by Darren Millane, who tragically died in a car accident in 1991. Geelong temporarily retired the number 5 between 1998 and 2005 after the retirement of Gary Ablett Sr. Sons of famous players will often take on their father's number, especially if they play at the same club. Sergio Silvagni and his son Stephen, for example, both wore number 1 for Carlton, with Stephen's son Jack later following suit. Matthew Scarlett wore his father John's number 30 at Geelong. In contrast, some sons of famous players prefer to take on other numbers in the hopes of forging their own identity, and to reduce the burden of having to fulfill high expectations. Notable examples of this are Gary Ablett Jr. at Geelong who wore number 29 and number 4 instead of his father's number 5, and Jobe Watson at Essendon, who passed up Tim's No. 32 in favour of number 4. The use of numbers higher than 60 is very rare. In 2017 eight indigenous players wore the number 67 as part of the Sir Doug Nicholls' Indigenous Round. This was to recognise the 50th anniversary of the 1967 Australian referendum confirming the citizenship of Indigenous Australians.[20] Number 65 was worn by Andrew Witts of Collingwood for one game in 1985, before switching to 45 for the remainder of the season.[21] There is an apocryphal story that number 82 was worn by Ernie Taylor of Richmond, in round 10 of 1925 against North Melbourne, but clubs do not have guernseys with numbers that high available for one-off games, and it is more likely this number was number 32 and misread by a local journalist. Established players will often trade the bigger numbers allocated to rookies for more prestigious lower numbers later in their career. Mal Brown of Claremont in the WAFL demonstrated a blatant disregard for this practice in 1975, trading his normal number 55 for number 100. Baseball In baseball, players (and uniquely to baseball, coaches as well) generally wear large numbers on the back of their jersey. Some jerseys may also feature smaller numerals in other locations, such as on the sleeves, pants, or front of the shirt. The purpose of numerals in baseball is to allow for easy identification of players. Some players have been so associated with specific numbers that their jersey number has been officially "retired". The first team to retire a number was the New York Yankees, which retired Lou Gehrig's No. 4 in 1939. According to common tradition, single-digit numbers are worn by position players but rarely by pitchers, and numbers higher than 60 are rarely worn at all.[22] Bigger numbers are worn during spring training by players whose place on the team is uncertain, and sometimes are worn during the regular season by players recently called up from the minor leagues; however, such players usually change to a more traditional number once it becomes clear that they will stay with the team.[22] However, this tradition is not enforced by any rule,[23] and exceptions have never been rare. Moreover, numbers greater than 60 have become much more popular among Major League players since 2010, for a variety of cultural reasons.[22] Examples include stars Kenley Jansen (74), Aaron Judge (99), Luis Robert (88), Josh Hader (71), Nick Anderson (70), Seth Lugo (67), Jose Abreu (79), and Hyun-Jin Ryu (99).[22] At the other end of the number line, Blake Snell (who wears No. 4) in 2018 became the first pitcher wearing a single-digit number to appear in the All-Star Game and the first to win the Cy Young Award.[24] In the early years of baseball, teams did not wear uniform numbers. Teams experimented with uniform numbers during the first two decades of the 20th century, with the first Major League team to use them being the 1916 Cleveland Indians which used them on their left sleeves for a few weeks before abandoning the experiment.[25] Again in 1923, the St. Louis Cardinals tried out uniforms with small numbers on the sleeves, but the players did not like them, and they were removed. For the 1929 Major League Baseball season both the New York Yankees and Cleveland Indians put numbers on their jerseys, the first two teams to do so, beginning a trend that was completed by 1937, when the Philadelphia Athletics became the last team to permanently add numbers to their jerseys.[26][27] The 1929 New York Yankees handed out uniform numbers based on a player's position in the batting order; which is why Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig wore their famous numbers 3 and 4; they batted third and fourth respectively that season. Numbers 1–8 were assigned to the regular starters at their respective batting order positions, numbers 9 and 10 were assigned to the Yankees' two backup catchers,[28] while pitchers and backup fielders were assigned higher numbers.[29] This is one source of the tradition against pitchers wearing single-digit numbers.[22] Baseball players choose their own number for personal reasons, or accept a number assigned by the team. The reasons that players choose a particular number vary widely. Bill Voiselle in the 1940s wore No. 96 in honour of his hometown of Ninety Six, South Carolina. Hall-of-Fame catcher Carlton Fisk in the 1980s wore No. 72 with the Chicago White Sox because a teammate was already using the No. 27 that Fisk had worn with his prior team, the Boston Red Sox. A number of players, often with iconoclastic personalities or with names featuring the letter "O", have worn No. 0 or No. 00, which are generally uncommon. Catcher Benito Santiago switched from No. 9 to No. 09 (with a leading zero) and wore the latter from 1991 to 1994 in an effort to make his uniform more comfortable, the only major league baseball player (or any major professional sportsman) known to have worn a leading zero (outside of basketball's common 00).[30] Eddie Gaedel, the midget at the centre of an infamous stunt by Bill Veeck's St. Louis Browns, is the only known major league player to have worn a fraction (1⁄8, which he had borrowed from the Browns' batboy) as his jersey number during his only major league plate appearance. Jerseys with three numbers are prohibited, although Bill Lee once tried to change his number to 337 since it spells "Lee" upside down.[citation needed] In 2020, Yankees pitcher Miguel Yajure became the first player to appear in an MLB game wearing No. 89, the last available unused number.[31] In Nippon Professional Baseball, the Japanese major leagues, No. 18 is often reserved for the ace pitcher.[32] Accordingly, a number of Japanese pitchers in MLB have worn the number. Examples include Kenta Maeda and Daisuke Matsuzaka. The number 42 is retired throughout organized baseball in honour of Jackie Robinson. Most independent professional leagues, though not bound by the rulings of the Commissioner of Baseball, have followed suit. During spring training in 2023, the Yankees' clubhouse director Lou Cucuzza suggested that teams should no longer be required to issue uniform numbers for non-player personnel. With the Yankees having retired 22 numbers, and with three other numbers being kept out of circulation, that left 75 numbers available for current personnel. The number crunch was most apparent in spring training, when the Yankees invited 69 players. Cucuzza noted that many Yankees coaches choose not to wear their full uniforms in the dugout during games. Also, many managers and coaches throughout MLB wear a hoodie over their uniform top. Cucuzza pitched the idea to an MLB executive; reportedly, MLB did not want to immediately make such a change, but did not formally turn it down.[33] Basketball American basketball leagues at all levels traditionally use single and double digits from 0 to 5 (i.e. 0, 00, 1–5, 10–15, 20–25, 30–35, 40–45, and 50–55). While numbering was relatively unrestricted at amateur levels in the sport's early decades, numbering rules in the NCAA and most amateur competitions evolved to mandate that only these numbers be used. This eases non-verbal communication between referees, who use fingers to denote a player's number, and the official scorer. In college basketball, single-digit players' numbers are officially recorded as having a leading zero.[34] However, starting in the 2023–24 season, the NCAA has returned to allowing all numbers from 0 to 99 in both men's and women's basketball.[35][36] The rule about "0" and "00" no longer applies in the NBA but previously, in 2000, Utah Jazz center Greg Ostertag changed from "00" to "39" so Olden Polynice could wear No. 0 and in 2003, Washington Wizards center Brendan Haywood switched from No. 00 to No. 33 so Gilbert Arenas (who had the nickname "Agent Zero" already at this point) could wear No. 0. Chicago Bulls backup guard Randy Brown wore No. 0 during the 1995–96 season, but switched to No. 1 after Robert Parish joined the team the following season. When Eric Montross joined the Boston Celtics in 1994, his preferred No. 00 had been taken off circulation after Parish's departure (it was eventually retired in 1998). Montross wore No. 0 in Boston, but would revert to No. 00 after leaving the Celtics in 1996. Since then, a number of NBA teams have featured players wearing both 0 and 00, such as the 2014 Denver Nuggets (Aaron Brooks and Darrell Arthur, respectively), the 2015–16 Denver Nuggets (Emmanuel Mudiay and Arthur), the 2016–17 Indiana Pacers (C. J. Miles and Brooks), the 2017–18 Cleveland Cavaliers (Kevin Love and Chris Andersen), the 2018–19 Portland Trail Blazers (Damian Lillard and Enes Kanter), the 2019–20 Portland Trail Blazers (Lillard and Carmelo Anthony), the 2020–21 Portland Trail Blazers (Lillard and Anthony), the 2021–22 Golden State Warriors (Jonathan Kuminga and Gary Payton II), the 2022–23 Golden State Warriors (Kuminga and Donte DiVincenzo), the 2022–23 Indiana Pacers (Tyrese Haliburton and Bennedict Mathurin), and the 2023–24 Indiana Pacers (Haliburton and Mathurin). The NBA has always allowed other numbers from 0 to 99, but use of digits 6 through 9 is less common than 0 through 5 since most players tend to keep the numbers that they had previously worn in college. However, with the increase in the number of international players, and other players who have been on national (FIBA) teams who change NBA teams and cannot keep their number with the previous team because another player has worn it or is retired, players have adopted such higher numbers (Patrick Ewing with No. 6 in Orlando). When Michael Jordan retired in 1993, the Chicago Bulls retired his 23; when he came out of retirement he chose to wear 45 until, during the 1995 NBA post-season, he went back to his familiar 23. Also, players cannot change numbers midseason, but they used to be able to (Andre Iguodala[37] and Antoine Wright changed from No. 4 and No. 15 to No. 9 and No. 21 for Chris Webber and Vince Carter, respectively). Since Kelenna Azubuike was inactive all season, Carmelo Anthony was able to wear Azubuike's No. 7 when traded to the Knicks in 2011, but since Rodney Stuckey was active, Allen Iverson could not wear No. 3 when traded to the Pistons in 2009. (Anthony would not have been able to wear his normal No. 15 anyway and would have had to trade jerseys; the Knicks have retired the jersey number). No NBA player has ever worn the number 69, which is believed to be implicitly banned due to its sexual connotations; the NBA has never confirmed this.[38] Dennis Rodman allegedly requested the number 69 when he joined the Dallas Mavericks but was refused and instead wore 70. The WNBA has aspects of NFHS (high schools), NBA, and NCAA numbering rules. Like the NBA and post-2023 NCAA, digits 6–9 are allowed; however, like NFHS and pre-2023 NCAA, no number higher than 55 is allowed. Also, since 2011, no player can wear 00. Up to 2014, players in FIBA-organized competitions for national teams, including the Olympic Games, World Cup and Women's World Championship (since renamed the Women's World Cup), had to wear numbers from 4 to 15, due to the limitations of the digits in the human hand: Referees signal numbers 1 to 3 using their fingers to the table officials to indicate the number of points scored in a particular shot attempt, whereas numbers 4–15 are shown by the referee using their fingers (with the hands shown sequentially instead of simultaneously for number 11 to 15 to signify two separate digits instead of a singular number) after a personal foul to indicate the offending player. The restriction was lifted following the implementation of video replay systems in basketball which allowed the table officials to quickly identify players on the court independently from the referees. Starting in 2014, under FIBA rules, national federations could also allow any numbers with a maximum of 2 digits for their own competitions; this rule also applied in transnational club competitions, most notably the EuroLeague.[39] FIBA extended this change to its own competitions in 2018. At present, players are allowed any numbers from 1 to 99, additionally 0 and 00.[40] USA Basketball, however, remains steadfast in using the pre-2018 FIBA numbering rules.[41] Cricket

The International Cricket Council does not specify criteria for numbering players,[43] so players choose their own jersey number.[44] The 1995–96 World Series Cup in Australia saw the first use of shirt numbers in international cricket, with most players assigned their number and some players getting to choose their number, most notably Shane Warne wearing 23 as it was his number when he played junior Australian rules football for St Kilda. Other countries soon adopted the practice, although players would typically have different numbers for each tournament, and it was several years later that players would consistently wear the same number year-round. Ricky Ponting (14) continued to use the same number as in that initial season.[45] Player numbering was first used in the 1999 Cricket World Cup, where the captains wore the number 1 jersey and the rest of the squad was numbered from 2 to 15.[46] An exception was that South African captain Hansie Cronje retained his usual number 5 with opener Gary Kirsten wearing the number 1 which he had also done previously. Shirt numbers no longer remain exclusive to the short forms of the game, and navy blue numbers are now used on the playing whites in the Sheffield Shield to aid spectators in distinguishing players. However, a recent fashion that has been taken up by several nations is the process of giving a player making his Test debut an appearance number, along with his Test cap, for reasons of historical continuity. The number represents how many players have made their Test debuts including the one wearing it. If two or more players make their debut in the same match, they are given numbers alphabetically based on surname. For example, Thomas Armitage is Test player number 1 for England. He made his debut in the very first Test Match, against Australia, on 15 March 1877, and was first in alphabetical order on England's team. Mason Crane made his debut for England on 4 January 2018 against Australia; his number is 683. These numbers can be found on a player's Test uniform, but it is always in discreet small type on the front, and never displayed prominently. Gaelic gamesFor Gaelic football and hurling, the GAA specifies that players must be numbered from 1 to 24 in championships organised by the body.[47] In camogie, the Association does not specify any criteria for numbering.[48] Apart from that, in Gaelic sports goalkeepers generally wear the number 1 shirt, and the rest of the starting team wears numbers 2–15, increasing from right to left and from defence to attack: substitutes' numbers start from 16. Gridiron footballAmerican footballNFL The NFL has used uniform numbers since its inception; through the 1940s, there was no standard numbering system, and teams were free to number their players however they wanted. An informal tradition had arisen by that point that was similar to the modern system; when the All-America Football Conference, which used a radically different numbering scheme, merged with the NFL in 1950, the resulting confusion forced the merged league to impose a mandatory system of assignment of jersey numbers in 1952.[49] This system was updated and made more rigid in 1973, and has been modified slightly since then.[50] In 2021, the system received a major expansion.[51] Numbers are always worn on the front and back of a player's jersey, and so-called "TV numbers" are worn on either the sleeve or shoulder. The Cincinnati Bengals were the last NFL team to wear jerseys without TV numbers on a regular basis in 1980, though since then several NFL teams have worn throwback uniforms without them, as their jersey designs predated the introduction of TV numbers. Players' last names, however, are required on all uniforms, even throwbacks which predate the last name rule. As of the 2018 season, numbers on shoulders are mandatory, only leaving helmet and pants numbers as optional.[52] Some uniforms also feature numbers either on the front, back, or sides of the helmet (in pro football, these were most prominently worn on the San Diego Chargers "powder-blue" uniforms). Players have often asked the NFL for an exception to the numbering rule; with very few exceptions (see, for example, Keyshawn Johnson), these requests are almost always denied. Below is the numbering system established by the NFL. Small changes were made on occasion after 1973, including opening up the 10–19 range for wide receivers in 2004,[53] and opening 40–49 up to linebackers in 2015, with the latter decree being named the "Brian Bosworth rule"; Bosworth wanted to wear 44, but was ordered to change it to 55.[54] In the same year, numbers 50–59 were opened to defensive linemen; the first benefactor was Jerry Hughes. In 2021, flexibility was increased due to expanded regular season and offseason rosters.[51] In 2023, NFL owners approved a rule allowing the use of the number 0 by all non-lineman positions.

Number 00 is no longer allowed, but it was issued in the NFL before the number standardization in 1973. Jim Otto wore number "00" during most of his career with the Oakland Raiders. Wide receiver Ken Burrough of the Houston Oilers also wore "00" during his NFL career in the 1970s. This NFL numbering system is based on a player's primary position. Any player wearing any number may play at any position at any time (though offensive players wearing numbers 50–79 or 90–99 must let the referee know that they are playing out of position by reporting as an "ineligible number in an eligible position"). It is not uncommon for running backs to line up at wide receiver on certain plays, or to have a lineman or linebacker play at fullback or tight end in short yardage situations. If a player changes primary positions, he is not required to change his number unless he changes from an eligible position to an ineligible one or vice versa (as such, Devin Hester got to keep his number 23 when changing his primary position from cornerback to wide receiver before the 2007 season). In preseason games, when teams have expanded rosters, players may wear numbers that are outside of the above rules. When the final 53-player roster is established, they are reissued numbers within the above guidelines. College and high schoolIn college football and high school football, a less rigid numbering system is employed. The only rule is that members of the offensive line (centers, guards, and tackles) that play in ineligible positions (those that may not receive forward passes) must wear numbers from 50 to 79. Informally, certain conventions still hold, and players often wear numbers in the ranges similar to their NFL counterparts; though the lowest numbers are often the highest prestige, and thus are often worn by players at any position. Kickers and punters are frequently numbered in the 40s or 90s, which are the least in-demand numbers on a college roster. The increased flexibility in numbering of NCAA rosters is needed because NCAA rules allow 85 scholarship players and rosters of over 100 players total; thus teams would frequently exhaust the available numbers for a position under the NFL rules. One oddity of college football is that the same squad number can be shared by two (or more) players, e.g., an offensive and a defensive player. Usually one of the players is a reserve who rarely plays but there are exceptions: In the 2009 and 2010 seasons, that same number (5) was worn by South Carolina starting quarterback Stephen Garcia and starting cornerback Stephon Gilmore. Gilmore was also used as a wildcat quarterback in games against Clemson in 2009 and Southern Miss in 2010. The player change, since both players wore the same number, caused some confusion among opposing defenses, but was legal, since both players were not on the field at the same time. In 2012, the No. 5 was worn by two Notre Dame starters—quarterback Everett Golson and linebacker Manti Te'o. If two players wearing the same number for the same team do appear on the field on a play, a five-yard illegal substitution penalty is assessed against the offending team. During a 2010 game against Bowling Green, Michigan mistakenly sent Martavious Odoms (wide receiver) and Courtney Avery (defensive back), both of whom wore #9, onto the field as part of a punt-return unit, and incurred the penalty. Avery switched to #5 following that game. Starting in the 2020 NCAA football season, the use of duplicate number will be restricted to only two players, and players will be allowed to wear No. 0.[55] High school football legalized No. 0 in 2022.[56] Canadian football Canadian football, such as that played at the university level in U Sports or professionally in the Canadian Football League (CFL), follows similar rules to amateur American football, with some minor exceptions. In the original numbering system, offensive linemen wore numbers from 40 to 69 and numbers 70–79 were allocated to receivers. A rules change in 2008 switched numbers 40–49 from offensive linemen to eligible receivers. Any eligible player, whether he is a quarterback, running back, receiver, or a kicker, can wear any eligible number. Doug Flutie wore his Boston College number of 22 when he played quarterback for the BC Lions and No. 20 for the Calgary Stampeders. Currently, numbers 1–49 and 70–89 are eligible while 50–69 are not. They can be used as ineligible players in eligible positions. Numbers 90–99 are generally worn on defense although in the early days of the CFL, 90s were common on offense. The number 0 (and 00) is also allowed in the CFL, although as beginning in the 2023 CFL season teams are not permitted to issue both 0 and 00 simultaneously. A defensive player can wear any number he chooses, regardless of the position he plays. HandballAccording to the International Handball Federation, players may wear numbers from 1 to 99.[57] Goalkeepers often wears the numbers 12 and 1. 16 is also common.[58] Field players usually have the remaining numbers from 1 to 20. Sometimes the players also have the last two digits of their birth year.[citation needed] Field hockeyIn field hockey, the International Hockey Federation (FIH) does not specify a criterion for numbering players.[59] Nevertheless, in the 2018 Men's and Women's World Cup, the 18 players of each squad were numbered 1–32,[60] with number "1" generally given to goalkeepers, with some exceptions such as Canada men's, with forward Floris van Son[61] or India women's with midfielder Navjot Kaur, both wearing that number.[62] In other hockey competitions controlled by the FIH, a similar numbering system (1–32 for squads made up of 18 players each) has been applied, such as the 2016 Summer Olympics for both, men's and women's squads.[63] This systems kept for the last men's and women's Champions Trophy held in Breda and Changzhou respectively.[64][65] Ice hockey The first group to use numbers on ice hockey uniforms is a matter of some debate. The Pacific Coast Hockey Association is sometimes credited with being the first to use numbered sweaters, but the National Hockey Association, the predecessor of the National Hockey League, is known to have required its players to wear numbered armbands beginning with the 1911–12 season, which may have come before that.[66] The Patrick brothers, who founded the PCHA, put numbers on players' backs so they could sell programs in which the players were listed by their numbers.[67] To start the 1977–78 season, the NHL placed into effect a rule that also required sweaters to display the names of the players wearing them, but Toronto Maple Leafs owner Harold Ballard initially refused to abide by it, fearing that he would not be able to sell programs at his team's games. The NHL responded by threatening to levy a fine on the team in February 1978, so Ballard, in malicious compliance, started having names put on the jerseys but made them the same color as the background they were on, which for the team's road jerseys was blue. The league threatened further sanctions, and despite playing more than one game with their "unreadable" sweaters, Ballard's Maple Leafs finally complied in earnest by making the blue jerseys' letters white.[66] The first jersey number to be retired in professional sports was that of an NHL player, Ace Bailey, whose number 6 was retired by the Toronto Maple Leafs in 1934 following a career-ending fight with Eddie Shore during a game against the Boston Bruins in 1933. Shore injured Bailey under the mistaken impression that Bailey had hip-checked him when it was actually fellow Maple Leaf Red Horner. To aid Bailey, the NHL hosted a benefit game between the Maple Leafs and an all-star team, at which Maple Leafs owner Conn Smythe retired Bailey's number.[68] Historically, starting NHL goaltenders wore the number 1. Popular belief holds that this was because the goaltender was the first player on the rink from the perspective of one standing in front of the net; this is also believed to be why replacement goaltenders would also wear the number. Further use of the number 1 among goaltenders can be attributed to adherence to tradition.[69] Over time, the number 1 became rare among NHL goaltenders, with only four rostered goalies using it as of the end of the 2023–24 NHL season: Lukáš Dostál of the Anaheim Ducks, Jeremy Swayman of the Boston Bruins, Ukko-Pekka Luukkonen of the Buffalo Sabres, and Devin Cooley of the San Jose Sharks. One reason was that goaltenders increasingly followed the example set by the Toronto Maple Leafs' Terry Sawchuk after the NHL mandated that each team have two goaltenders in every game. In 1964, Sawchuk joined the Maple Leafs wearing 24, as the number 1 was already being used, but switched to 30, starting a trend of goaltenders using numbers in the 30s. Nowadays, some goalies have worn the numbers 40 and 41 in goal in addition to numbers in the 30s, with Anthony Stolarz wearing 41 for the Toronto Maple Leafs and Alexandar Georgiev wearing 40 for the San Jose Sharks for example. Also, seven franchises have retired the number 1—six in honor of players and one, the Minnesota Wild, in honor of its fanbase—making it unavailable. As a result, fewer goalies have chosen the traditional number 1 and instead have opted for more distinctive numbers, or numbers of their favourite goalies. Notable examples include Jacob Markström wearing 25 for the New Jersey Devils, Pyotr Kochetkov wearing 52 for the Carolina Hurricanes, Jake Oettinger wearing 29 for the Dallas Stars, Jordan Binnington wearing 50 for the St. Louis Blues, Joseph Woll wearing 60 for the Toronto Maple Leafs, Karel Vejmelka wearing 70 for the Utah Hockey Club, Sergei Bobrovsky wearing 72 for the Florida Panthers, Dan Vladar wearing 80 for the Calgary Flames, Elvis Merzļikins wearing 90 for the Columbus Blue Jackets, Andrei Vasilevskiy wearing 88 for the Tampa Bay Lightning, Juuse Saros wearing 74 for the Nashville Predators, Ivan Fedotov wearing 82 for the Philadelphia Flyers, and Logan Thompson wearing 48 for the Washington Capitals.[69][70] The NHL no longer permits the use of 0 or 00 as the league's database cannot list players with such numbers,[69] and in 2000 the league retired the number 99 for all member teams in honor of Wayne Gretzky.[71] The last number to go unused in the NHL was 84, and Canadiens forward Guillaume Latendresse became the first to wear it at the start of the 2006–07 season.[72] Auto racingIn most auto racing leagues, cars are assigned numbers. The configuration of stock cars, however, makes the numbers much more prominent. (Aerodynamic open-wheel cars do not have nearly the amount of flat surface that a stock car has.) Numbers are often synonymous with the drivers that carry them. Dale Earnhardt Sr. is associated with the number 3 (although that number is actually associated more with its owner, Richard Childress, who has taken the number out of reserve for his grandson Austin Dillon, first in the Truck Series, then in the Nationwide Series, and finally in the Cup Series beginning in 2014), while Richard Petty is associated with number 43, Wood Brothers Racing with number 21, and Jeff Gordon with the number 24. NASCAR In NASCAR, numbers are assigned to owners and not specific drivers. Drivers that spend a long time on a single race team often keep their numbers as long as they drive for the same owners. When drivers change teams, however, they take a new number that is owned by that team. Jeff Burton, for example, raced for three teams from 1994 to 2013, and had four numbers in that time. In 1994 and 1995 he raced the number 8 car, then owned by the Stavola Brothers. From 1996 to mid-2004 he raced for Roush Racing, and drove the Number 99 car. After leaving Roush Racing for Richard Childress Racing, he changed to car number 30 (for the rest of the 2004 season) and drove number 31 (also an RCR car) from 2005 to 2013. The number 99 car he used to drive for Roush was driven by Carl Edwards from 2004 to 2014. When Dale Earnhardt Jr., having raced under number 8 at Cup level, moved from DEI to Hendrick Motorsports, he attempted to take the number with him. When that failed Hendrick was able to secure the number 88 from Robert Yates Racing. Unlike most other racing leagues, number 1 is just another number anyone can use in NASCAR. As of 2022, Trackhouse Racing fields the number 1 car for Ross Chastain following Trackhouse purchasing Chip Ganassi Racing's NASCAR operations. Formula One Formula One car numbers started to be permanently allocated for the whole season in 1974. Prior to this numbers were allocated on a race-by-race basis by individual organisers. From 1974 to the mid-1990s, the numbers 1 and 2 were allocated to the reigning world champion and his teammate, swapping with the previous year's champions. Once numbers had been allocated, teams retained the same numbers from year to year, only exchanging for 1 and 2 when the drivers' World Championship was won. As a result, Ferrari are infamous for having carried 27 and 28 for many years (every season from 1980 to 1989, and then again from 1991 to 1995), these numbers having originally been allocated to new entrant Williams in 1977 and passed to Ferrari when Alan Jones replaced Jody Scheckter as World Champion after the 1980 season. Numbers were reallocated occasionally as teams departed and joined the series, but this scheme persisted until the late 1990s; one team, Tyrrell, kept the same numbers (3 and 4) throughout this period for every season from 1974 to 1995. The system was changed again in 1996. From that point through 2013, numbers were assigned annually, first to the reigning World Champion driver (who received number 1) and then his team-mate (who received number 2); after that the numbers were assigned to constructors sequentially according to their position in the previous season's Constructors' Championship, so that numbers were allocated (if the reigning champion is not driving for the reigning constructor's champion team) from 3 and 4, 5 and 6, and so on (skipping 13 with the seventh-placed team using 14 and 15). The only stipulation was that the World Drivers' Champion was entitled to the number 1 car regardless of the constructor's results; this was relevant when the winning driver's team failed to win the Constructors Championship, or if the winning driver changed teams after winning the championship—for example, when Damon Hill moved to the Arrows team for the 1997 season. This situation happened again in 2007 when 2006 champion Fernando Alonso left Renault to join McLaren, earning him and his rookie teammate, Lewis Hamilton, the numbers 1 and 2; and again in 2010 when Jenson Button moved to McLaren from Brawn GP.  Originally if a driver won the World Championship but did not defend their title the following season, tradition dictated that the number 1 was not allocated; the reigning World Constructors Champions then received numbers 0 and 2. Damon Hill received car number 0 in 1993 due to Nigel Mansell's move to Championship Auto Racing Teams (CART) in the U.S., and again in 1994, this time due to Alain Prost's retirement. This tradition has not always been in place; Ronnie Peterson received number 1 in the 1974; although he did not win the championship the previous year, due to Jackie Stewart's retirement, his Lotus team was allowed to keep number 1 as they had won the constructors' title. Feeder series Formula 2 and Formula 3 continue to use this numbering scheme, though 18 and 19 haven't been seen in Formula 2 since Anthoine Hubert's fatal accident in Formula 2 running number 19. The 2014 season was the first with a new system, in which drivers are assigned numbers for their entire careers. Under this system, similar to that used in MotoGP, drivers may choose any (available) number from 2 to 99, with number 1 reserved for the reigning drivers' champion. The champion's "regular" number is placed in reserve while that driver is using number 1, preventing other drivers from using that number. Since Jules Bianchi's fatal accident at Suzuka in 2014, Formula One has not issued Bianchi's number 17 as a mark of respect.[73] During Lewis Hamilton's spell as champion, he had declined use of the number 1, with number 44 being used for marketing purposes. Only two drivers have used number 1 since this new system's implementation. Sebastian Vettel, who had used the number 1 in four seasons spanning 2011–2014, and Max Verstappen, who is using the number 1 in 2022 after his championship win in 2021. Since the introduction of permanent race numbers in 2014 the lowest number to not have been selected is number 15. The 2014 season also saw the first time a car had raced with the number 13 since 1976; with Pastor Maldonado opting to take number 13 as his driver number. Since 2015, if a driver leaves the sport for whatever reason their number is held in abeyance for two seasons before it is becomes free to use again, since the introduction of this rule, ten numbers have been reused, These being, number 2 (Stoffel Vandoorne & Logan Sargeant); number 4 (Max Chilton & Lando Norris); number 6 (Nico Rosberg & Nicholas Latifi); number 9 (Marcus Ericsson & Nikita Mazepin); number 10 (Kamui Kobayashi & Pierre Gasly); number 21 (Esteban Gutierrez and Nyck de Vries); number 22 (Jenson Button & Yuki Tsunoda); number 28 (Will Stevens & Brendon Hartley); number 88 (Rio Haryanto & Robert Kubica); number 99 (Adrian Sutil & Antonio Giovinazzi). A similar system is used in many European-style championships at national and international level; the champion receives number 1, and others are allocated either by a driver's placing in the previous season (third place the year before equates to race number 3) or by the team's placing in the team/constructor championship. If the championship driver does not return, the championship team is allowed to use number 1.   IndyCarDuring the USAC era of Indy car racing, it was traditional for the defending champion to carry No. 1 during the season. This rule had one exception; at the Indianapolis 500. The previous year's Indy 500 winner traditionally utilized No. 1 in the Indy 500 that particular year. The defending national champion would have to select a different car number for Indy only, unless they happened to also be the defending Indy 500 winner, sometimes swapping numbers with the other affected driver. There were typical exceptions to the rule, as some defending champions decided against using No. 1, preferring instead to maintain their identity with the number associated with the team. During the CART era, car numbers 1–12 were assigned based on the previous season's final points standings. Number 13 was not allowed, and starting in 1991, No. 14 was formally assigned to A. J. Foyt Enterprises. The remaining numbers 15–99 were generally allocated to the rest of the teams on first-come, first-served basis. Again at Indianapolis only, the No. 1 was set aside for use by the defending Indy 500 winner, if they so choose to use it, since it was a USAC-sanctioned race. Some teams in the top 12 chose not to utilize their assigned number, instead preferring a personal favorite number. For example, Penske has used 2 and 3 since 1994. Also, Newman-Haas Racing exchanged the No. 2 with Walker Racing to get the No. 5, after Nigel Mansell joined the team in 1993, 5 having been his long-used number in Formula One. "Unused" numbers from 1–12 reverted to the general pool, and could be used by any of the remaining teams. In the current IndyCar era, No. 1 is set aside for use by the previous season's championship entry. However, the majority of champions since 1998 have ignored the tradition at the request of teams or sponsors to maintain their team identity, and some drivers or teams have used their car numbers in social media accounts. The 1998 IndyCar championship team was A. J. Foyt Enterprises, which kept the traditional No. 14, while Panther Racing kept the No. 4, identified with team minority owner Jim Harbaugh, who wore it for the majority of his NFL career (except for his year in Charlotte, where John Kasay wore that number, he wore Foyt's No. 14). Chip Ganassi Racing has traditionally declined No. 1 as it was used after their 2003 season championship because of their poor performance the next season, and in recent years with PNC Financial Services has marketed a "Bank on the 9" campaign based on its number. In one case, at the 2012 Indianapolis 500, defending national champion Dario Franchitti, who normally used No. 10 and had the right to No. 1, chose to use No. 50 at that race for the 50-year anniversary of sponsor Target, which has been car owner Chip Ganassi's sponsor since 1990. In the 2009 Firestone Indy 300, British driver Alex Lloyd used number 40202, in reference to the phone text message number of a campaign to donate to Susan G. Komen for the Cure. (It was listed as No. 40 for purposes of computer timing.) OthersIn other forms of auto racing, such as sprint car racing or motorcycle racing, it is not uncommon to see the use of triple-digit numbers or alphanumeric combinations with a single letter, either as a prefix or suffix. Rugby leagueIn rugby league each of the thirteen positions on the field traditionally has an assigned shirt number, for example fullback is "1". In recent times squad numbering has been used for marketing purposes in the Super League competition. In Super League each player is given a squad number for the whole season, the first choice starting line-up at the beginning of the season will usually be given shirts 1–13 but as interchanges (substitutions) occur during the game and injuries etcetera occur during the season, it is less likely that the number a player wears will match the position they are playing. The position and numbers are as follows:

The four players on the interchange bench are numbers 14 to 17 but are simply named as Interchanges as the players can be played at any on-field position, although teams tend to have mostly forwards (positions 8 to 13) as interchange players as these are the positions that do more of the tackling and tire more quickly.[74]

Rugby union When included in the starting line-up, a player's rugby shirt number usually determines their position. Numbers 1–8 are the 'forwards', and 9–15 the 'backs'. Rugby union even has a position named simply after the shirt normally worn by that player in the "Number 8" position. Several clubs (Leicester and Bristol particularly) used letters instead of numbers on shirts, although have now been forced into line with the rest of the clubs.

Other sports Other sports which feature players with numbered shirts, but where the number that may be worn is not relevant to the player's position and role are: In water polo, players wear swim caps bearing a number. Under World Aquatics rules, the starting goalkeeper wears Number 1, the substitute goalkeeper wears Number 13, and remaining players wear numbers 2 though 12. In road bicycle racing, numbers are assigned to cycling teams by race officials, meaning they change from race to race. Each team has numbers in the same group of ten, excluding multiples of ten, for example 11 through 19 or 21 through 29. If a race has squads of smaller than nine, each still uses numbers from the same group of ten, perhaps 31 through 36 where the next squad will have 41 through 46. Usually, but not always, the rider who wears a number ending in 1 is the squad's leader and the one who will try for a high overall placing. If the race's defending champion is in the field, he or she wears number 1. In floorball, all players are required to have number 1–99 on their jersey, but goalies are the only players who can wear number 1. In volleyball competitions organised by the FIVB, players must be numbered 1–20.[75] Retired numbers Retiring the uniform number of an athlete is an honor a team bestows on a player, usually after the player has left the team, retires from the game, or has died. Once a number is retired, no future player from the team may use that number, unless the player so-honored permits it. Such an honor may also be bestowed on players who had their careers ended due to serious injury. In some cases, a number can be retired to honor someone other than a player, such as a manager, owner, or a fan. For example, the Boston Celtics retired the squad number 1 in honor of the team's original owner Walter A. Brown. This is usually done by individual teams. In association football, the practise of retiring numbers started in the 1990s, when clubs assigned permanent numbers for their players, first in European Premier League or Serie A and then in South American leagues such as Argentine Primera División. Nevertheless, associations such as CONMEBOL have squads numbering rules that do not allow the retiring of numbers. Moreover, some South American teams (such as Universitario de Deportes or Flamengo, and even Mexican teams invited for the occasions) have occasionally had to re-issue their retired numbers for special cases due to CONMEBOL rules for club and national team competitions (Copa Libertadores, Copa América). In cricket also, there is a practice of retiring certain numbers to honour great players associated with the sport or league. For example, in the Indian Premier League (IPL) of India, recently the club Royal Challengers Bangalore retired the jerseys of two great players, AB de Villiers and Chris Gayle.[76] They had jersey numbers of 17 and 333.[76] See also

References

Further reading

External links |

Portal di Ensiklopedia Dunia