|

November 1882 geomagnetic storm

The Aurora of November 17, 1882 was a geomagnetic storm and associated aurora event, widely reported in the media of the time. It occurred during an extended period of strong geomagnetic activity in solar cycle 12. The event is particularly remembered in connection with an unusual phenomenon, an "auroral beam", which was observed from the Royal Observatory, Greenwich by astronomer Edward Walter Maunder and by John Rand Capron[1] from Guildown, Surrey. Magnetic effectsThe magnetic storm that caused the brilliant auroral display of November 1882 was reported in The New York Times and other newspapers as having an effect on telegraph systems, which were rendered useless in some cases.[2] The Savannah Morning News reported that "the switchboard at the Chicago Western Union office was set on fire several times, and much damage to equipment was done. From Milwaukee, the 'volunteer electric current' was at one time strong enough to light up an electric lamp".[2] Measurements taken in the United Kingdom, where the telegraph also was affected, indicated that a telluric current five times stronger than normal was present.[3] AuroraePolar observationsDuring the event, bright auroral phenomena were recorded from across the world, including several observations from polar latitudes, thanks to the event occurring during the First International Polar Year. In one case, two members of the ill-fated Lady Franklin Bay Expedition, including the astronomer, Edward Israel, while observing at Fort Conger near the north magnetic pole, instinctively ducked to avoid an aurora described as "as bright as the full moon".[4][5] Observations in the United StatesThe Philadelphia Inquirer of November 18 reported a "brilliance as bright as daylight" at Cheyenne, and a "blood red" sky at St Paul.[2] In a 1917 paper for the National Academy of Sciences, the electrical engineer, Elihu Thomson, described seeing "colored streamers passing upward from all around towards the zenith from north, east, west and south", with "great masses or broad bands to the east and west".[6] Capron's beam - Philosophical Magazine, May 1883 The most unusual phenomenon of the auroral storm, witnessed from Europe at approximately 6 p.m. on November 17, was described in detail in various ways, including as a "beam", "spindle", "definite body" with a "Zeppelin"-like shape and pale green colour, passing from horizon to horizon above the Moon.[7] The phenomenon, which transited the sky in approximately seventy-five seconds, was witnessed and documented by the amateur scientist and astronomer, John Rand Capron, at Guildown, Surrey. Capron made a drawing of what he referred to as the "auroral beam"; it subsequently was published along with an article in the Philosophical Magazine.[1] In the article, Capron collected twenty-six separate accounts, of which the majority came from the United Kingdom: these included reports of the object's torpedo-shaped appearance and an apparent dark nucleus.[7] Several of Capron's correspondents speculated that the phenomenon might have been a meteor, but Capron (and Maunder, who wrote a note in The Observatory on Capron's study) thought it could have represented a transient illumination of an otherwise invisible auroral arc.[8] The writer, Charles Hoy Fort, later referred to this incident in his book The Book of the Damned, in which he collected further reports from various articles (including several in the journal Nature) published both at the time and subsequently:

Although Fort suggested the event had supernatural overtones, scientific opinion was that the "beam" likely represented an extremely unusual auroral phenomenon. Maunder commented:

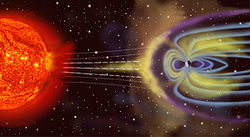

Solar phenomenaIn a 1904 article, Maunder was to describe the storm as a "very intense and long-continued disturbance", which in total, lasted between November 11 and 26. He pointed out that this synchronised "with the entire passage across the visible disc" of sunspot group 885 (Greenwich numbering).[11] This group originally had formed on the disc on October 20, passed off at the west limb on October 28, passed again east–west between November 12–25, and returned at the east limb on December 10, before finally disappearing on the disc on December 20.[12] The association of the November 1882 sunspot, or group of sunspots, with the strong auroral display, the collapse of the telegraph system, and variations in the magnetic readings taken at Greenwich was to prompt Maunder to pursue further research of the link between sunspots and magnetic phenomena.[13] See alsoReferences

|

||||||||||||||

Portal di Ensiklopedia Dunia