|

Northwest Airlines Flight 253

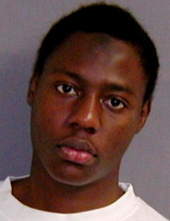

The attempted bombing of Northwest Airlines Flight 253 occurred on December 25, 2009, aboard an Airbus A330 as it prepared to land at Detroit Metropolitan Airport following a transatlantic flight from Amsterdam. Attributed to the terrorist organization al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP), the act was undertaken by 23-year-old Nigerian national Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab using chemical explosives sewn to his underwear.[3] These circumstances, including the date, led to Abdulmutallab being commonly nicknamed either the "Underwear bomber"[4] or "Christmas Day bomber" by American media outlets. It also could have been the worst plane crash in the history of Michigan beating out Northwest Airlines Flight 255. The event was the second airliner bombing attempt in the United States in eight years, following the 2001 American Airlines Flight 63 bombing attempt. If successful, the attack would have surpassed American Airlines Flight 191 as the deadliest airplane crash on U.S. soil and tied Iran Air Flight 655 as the eighth-deadliest of all time. It was also the second event in 2009 involving an Airbus A330 (after the June 1 crash of Air France Flight 447), and the final operational occurrence for Northwest Airlines (preceding that airline's merger with Delta Air Lines the following month). For his role in the plot, Abdulmutallab was convicted as a civilian criminal in U.S. federal court and sentenced to life imprisonment without parole.[5] AQAP leader Anwar al-Awlaki, who reportedly inspired Abdulmutallab and "masterminded" the attack,[6] was killed two years later as the target of a drone strike in Yemen. Sequence of eventsPreparationOn December 16, 2009, Abdulmutallab visited the KLM Royal Dutch Airlines office in Accra, Ghana and paid $2,831 in cash for a Lagos-Amsterdam-Detroit round-trip ticket, with a January 8, 2010, return date.[7] At the time, Ghana and Nigeria were reportedly cash-based economies, making it normal for airplane tickets to be purchased in this manner.[8] Initially, it was rumored by some media outlets that Abdulmutallab had tried to fly to Detroit because it was a major hub of the U.S. automotive industry. The Associated Press later reported that Abdulmutallab chose Detroit because its flights had the least-expensive fares compared to other U.S. destinations like Chicago and Houston.[9] Eight days later on December 24, he departed Ghana's Kotoka International Airport on Virgin Nigeria Flight 804, bound for Murtala Muhammed Airport in Lagos, Nigeria. Abdulmutallab then connected at 23:00 local time to KLM Flight 588, a red-eye service from Lagos to Amsterdam operated by a Boeing 777.[10] Upon his arrival at Schiphol Airport, Abdulmutallab checked in for Northwest Airlines Flight 253 with only carry-on luggage. Bombing attempt Flight 253 was serviced by an Airbus A330-323E (registered N820NW, serial number 0859) transporting 279 passengers, 8 flight attendants, and 3 pilots.[11] The plane departed Amsterdam around 08:45 local time and was scheduled to arrive in Detroit at 11:40 EST.[12] As the plane approached Detroit, passengers aboard the flight recalled seeing Abdulmutallab enter a lavatory for about 20 minutes. After returning to his window seat at 19A (near the fuel tanks and wing),[13] he complained of an upset stomach[14] and was seen pulling a blanket over himself.[15] About 20 minutes prior to landing, he attempted to ignite a small explosive device consisting of plastic explosive powder[16][17] sewn to his underwear,[18] by injecting it with acid from a syringe to cause a chemical reaction.[19] While a small explosion and fire occurred, the device failed to detonate properly.[15][20] Passengers heard popping noises resembling firecrackers, smelled an odor, and saw the suspect's pants, leg and the wall of the plane on fire.[15]

— Passenger on Flight 253, on witnessing the failed attack.

There were no air marshals on the flight,[22] but several passengers and crew noticed the explosion. Dutch passenger Jasper Schuringa, seated in the same row, saw Abdulmutallab sitting and visibly shaking. He tackled and overpowered him.[23][24] Schuringa saw the suspect's pants were open, and that he was holding a burning object. "I pulled the object from him and tried to extinguish the fire with my hands and threw it away," said Schuringa, who suffered burns to his hands. Meanwhile, flight attendants extinguished the fire with a fire extinguisher and blankets,[15][25] and a passenger removed the partially melted, smoking syringe from Abdulmutallab's hand.[15]  Schuringa grabbed the suspect, and pulled him to the business class area at the front of the plane.[23][26] A passenger reported that Abdulmutallab, though burned "quite severely" on his leg, seemed "very calm," and like a "normal individual."[27] Schuringa stripped off the suspect's clothes to look for additional weapons, and he and a crew member restrained Abdulmutallab with plastic handcuffs. "He was staring into nothing" and shaking, said Schuringa.[23] Passengers applauded as Schuringa walked back to his seat.[26] The suspect was isolated from other passengers until after the plane landed.[20] A flight attendant asked Abdulmutallab what he had in his pocket, and the suspect replied: "Explosive device." When the attack triggered a fire indicator light within the cockpit, the pilot requested rescue and law enforcement personnel. The plane made an emergency landing at Detroit Metropolitan Wayne County Airport in the Downriver Detroit community of Romulus, Michigan.[15]  The Toronto Star reported that the plane's flight route would have had it over Canadian airspace when the attempted bombing occurred. Representatives of two pilot associations told the Star that Detroit Metro airport would have been the nearest suitable airport at which to attempt an emergency landing.[28] PostflightWhile the plane suffered relatively little damage,[29] the suspect incurred first and second degree burns to his hands, as well as second-degree burns to his right inner thigh and genitalia. Two other passengers were also injured.[30][31] When the plane landed, Abdulmutallab was handed over to U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) officers, and taken into custody for questioning and treatment of his injuries in a secured room of the burn unit of the University of Michigan Medical Center in Ann Arbor.[32] Schuringa was also taken to the hospital.[26] One other passenger incurred minor injuries.[33][34] Immediately after his arrest, Abdulmutallab talked to authorities about the plot for about 50 minutes, without having been informed of his Miranda rights. After emerging from surgery, he was informed of his rights and stopped talking to investigators for several weeks.[35] Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) agents, led by Special Agent in Charge Andrew Arena, arrived at the airport after the plane landed.[36] The aircraft was moved to a remote area so authorities could re-screen the plane, the passengers, and the baggage on board.[37] A bomb-defusing robot was first used to board the plane,[33] and the Transportation Security Administration (TSA) interviewed all passengers.[25] Another passenger from the flight was placed in handcuffs after a dog alerted officers to his carry-on luggage; he was searched, and released without charges.[38][39][40] While for several days thereafter federal officials denied that this second handcuffing had occurred, they later reversed this position, and confirmed that a second passenger had indeed been handcuffed.[41] Key peopleUmar Farouk Abdulmutallab The perpetrator of the attack was Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab, a 23-year-old Nigerian born into a wealthy-class family.[33][42] Abdulmutallab was raised in Kaduna, in Nigeria's Muslim-dominated north, a place he returned to on his vacations.[43][44] In high school at the British International School in Lomé, Togo.[26] Abdulmutallab was known to be a devout Muslim, who frequently discussed Islam with schoolmates.[45] He visited the U.S. for the first time in 2004.[46] For the 2004–05 academic year, Abdulmutallab studied at the San'a Institute for the Arabic Language in Sana'a, Yemen, and attended lectures at Iman University.[47][48] He began his studies at University College London in September 2005,[49] where he was president of the school's Islamic society in 2006 and 2007, during which time he participated in, along with political discussions, such activities as martial arts and paintballing.[50][51] During those years, he came to the attention of MI5, the UK's domestic counter-intelligence and security agency, for radical links and connections with Islamic extremists. To protect his privacy, they did not pass the information along to American officials.[52][53] On June 12, 2008, Abdulmutallab applied for and received from the U.S. consulate in London a U.S. multiple-entry visa, valid to June 12, 2010, with which he visited Houston, Texas, from August 1–17, 2008.[54][55] In May 2009, Abdulmutallab tried to return to Britain, supposedly for a six-month "life coaching" program at what the British authorities concluded was a fictitious school; accordingly, his visa application was denied by the United Kingdom Border Agency.[45] His name was placed on a UK Home Office security watch list, which meant he was not permitted to enter the UK, though he could pass through the country in transit and was not permanently banned. The UK did not share the information with other countries.[56] Abdulmutallab returned to the San'a Institute to study Arabic from August to September 2009.[57][58] "He told me his greatest wish was for sharia and Islam to be the rule of law across the world", said one of his classmates at the institute.[50] Abdulmutallab left the institute after a month, but remained in Yemen.[50] Earlier, his family had become concerned in August when he called them to say he had dropped the course, but was remaining there.[43] By September, he routinely skipped his classes at the institute and attended lectures at Iman University, which intelligence officials from the United States suspected to have links to terrorism.[50] The San'a Institute obtained an exit visa for him at his request, and arranged for a car that took him to the airport on September 21, 2009 (the day his student visa expired), but the school's director said, "After that, we never saw him again, and apparently he did not leave Yemen".[58] In October, Abdulmutallab told his father via text message saying that he did not want to attend business school in Dubai, and wanted instead to study Islamic law and Arabic in Yemen. When his father refused to pay for it, Abdulmutallab said he was "already getting everything for free".[50] He text-messaged his father, saying "I've found a new religion, the real Islam", "You should just forget about me, I'm never coming back", and "Forgive me for any wrongdoing, I am no longer your child".[43][50] The family was last in contact with their son in October 2009.[59] On November 11, 2009, British intelligence officials sent the U.S. a message indicating that a man named "Umar Farouk" had spoken to Anwar al-Awlaki, a Muslim spiritual leader supposedly tied to al-Qaeda, pledging to support jihad, but the notice did not mention Abdulmutallab by name.[60] On November 19, his father reported to two CIA officers at the U.S. Embassy in Abuja, regarding his son's "extreme religious views",[43][61] and told the embassy that Abdulmutallab might be in Yemen.[62] Acting on the report, the U.S. added Abdulmutallab's name in November 2009 to its 550,000-name Terrorist Identities Datamart Environment, a database of the U.S. National Counterterrorism Center. It was not added, however, to the FBI's 400,000-name Terrorist Screening Database, the terror watch list that feeds both the 14,000-name Secondary Screening Selectee list and the U.S.'s 4,000-name No Fly List.[63] Abdulmutallab's U.S. visa was not revoked either.[50] Yemeni officials said that Abdulmutallab left Yemen on December 7 (flying to Ethiopia, and two days later to Ghana).[57][58] Ghanaian officials said Abdulmutallab was there from December 9 until December 24, when he flew to Lagos.[64] Two days after the attack, Abdulmutallab was released from the hospital in which he had been treated for burns sustained during the attempted bombing. He was taken to the Federal Correctional Institution, Milan, a federal prison in York Charter Township, Michigan, near Milan.[65][66][67] Anwar al-Awlaki A number of sources reported contacts between Abdulmutallab and Anwar al-Awlaki, the late Muslim lecturer and spiritual leader who the U.S. accused as a senior al-Qaeda talent recruiter and motivator. al-Awlaki, previously an imam in the U.S., who had moved to Yemen, also had links to three of the 9/11 hijackers, the 2005 London subway bombers, a 2006 Toronto terror cell, a 2007 plot to attack Fort Dix, and the 2009 suspected Fort Hood shooter, Nidal Malik Hasan.[68][69] In 2006, he was banned from entering the UK; al-Awlaki repeatedly used a video link for public speeches from 2007 to 2009.[70] The Sunday Times reported that Abdulmutallab first met and attended lectures by al-Awlaki in 2005, when he was in Yemen to study Arabic.[52] He attended a sermon by al-Awlaki at the Finsbury Park Mosque.[6] Fox News reported that Abdulmutallab repeatedly visited Awlaki's website and blog.[71] CBS News and The Daily Telegraph reported that Abdulmutallab attended a video teleconference talk by al-Awlaki at the East London Mosque.[70][72] CBS News reported that the two had communicated in the months before the bombing attempt, and other sources have said that at a minimum, al-Awlaki was providing spiritual support for Abdulmutallab and the attack.[73] According to federal sources, over the year prior to the attack, Abdulmutallab had repeatedly communicated with al-Awlaki.[74] Intelligence officials suspected that al-Awlaki may have told Abdulmutallab to go to Yemen for al-Qaeda training.[6] One government source described intercepted "voice-to-voice communication" between the two during the fall of 2009, saying that al-Awlaki "was in some way involved in facilitating [Abdulmutallab]'s transportation or trip through Yemen. It could be training, a host of things."[75] Abdulmutallab reportedly told the FBI that he had trained under al-Awlaki at an al-Qaeda training camp in Yemen.[76][77] Yemen's Deputy Prime Minister for Defense and Security Affairs, Rashad Mohammed al-Alimi, said Yemeni investigators believe the suspect traveled in October to Shabwa, where he may have obtained the explosives and received training. He met with suspected al-Qaida members in a house built by al-Awlaki and used by al-Awlaki to hold religious meetings.[78] "If he went to Shabwa, for sure he would have met Anwar al-Awlaki," al-Alimi said. Al-Alimi also said he believed al-Awlaki was alive.[79] And Abdul Elah al-Shaya, a Yemeni journalist, said a healthy al-Awlaki called him on December 28 and said that the Yemeni government's claims as to his death were "lies". Shaya declined to comment as to whether al-Awlaki had told him about any contacts he may have had with Abdulmutallab. According to Gregory Johnsen, a Yemeni expert at Princeton University, Shaya is generally reliable.[80] At the end of January 2010, a Yemeni journalist, Abdulelah Hider Sha'ea, said he met with al-Awlaki, who told Sha'ea that he had met and spoken with Abdulmutallab in Yemen in late 2009. Al-Awlaki also reportedly called Abdulmutallab one of his students, said that he supported what Abdulmutallab did but did not tell him to do it, and that he was proud of Abdulmutallab. A New York Times journalist who listened to a digital recording of the meeting said that while the tape's authenticity could not be independently verified, the voice resembled that on other recordings of al-Awlaki.[81] Al-Awlaki released a tape in March 2010, in which he said, in part:

Beginning December 18, 2009, President Obama authorized attacks on suspected Al-Qaeda bases in Yemen. On April 6, 2010, The New York Times reported that President Obama had authorized the targeted killing of al-Awlaki.[83] Al-Qaeda in Yemen released a video in 2010 that showed Abdulmutallab and others training in a desert camp. The tape includes a statement from Abdulmutallab justifying his actions against "the Jews and the Christians and their agents."[84] Al-Awlaki was killed in a U.S. airstrike in Yemen on September 30, 2011.[85] Al-Qaeda involvementOn December 28, 2009, Obama, in his first address after the incident, said that the event "demonstrates that an alert and courageous citizenry are far more resilient than an isolated extremist".[86] On the same day, Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) announced that it was responsible for the attempted bombing. AQAP said that the attack, during "their [Americans'] celebration of the Christmas holidays", was to "avenge U.S. attacks on the militants in Yemen".[87][88] On January 24, an audio tape said to be from Osama bin Laden praised the bombing attempt and warned of further attacks against the United States, but did not claim responsibility for it.[89] The short recording, which was broadcast on Al Jazeera television, said: "The message delivered to you through the plane of the heroic warrior Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab was a confirmation of the previous messages sent by the heroes of the September 11."[90][91] An adviser to the U.S. president said he could not confirm whether the voice was that of bin Laden. In the past, the CIA has usually confirmed Al Jazeera reports on tapes attributed to bin Laden.[92] While in custody, Abdulmutallab told authorities he had been directed by al-Qaeda. He said he had obtained the device in Yemen, and was told to detonate it when the plane was over the United States.[26] Abdulmutallab said he had contacted al-Qaeda through a radical Yemeni imam (who according to The New York Times on December 26 was not believed to be al-Awlaki)[55] whom he had reached through the internet.[31] The New York Times reported on December 25 that a counter-terrorism official had told them Abdulmutallab's claim of connection with al-Qaeda "may have been aspirational".[93] But U.S. Representative Jane Harman (D-Calif.), Chairman of the House Homeland Security Subcommittee on Intelligence, Information Sharing, and Terrorism Risk Assessment, said the following day that a federal official briefed lawmakers about "strong suggestions of a Yemen-al Qaeda connection" with the suspect.[94] On January 2, 2010, President Obama said that AQAP trained, equipped, and dispatched Abdulmutallab, and vowed retribution.[95][96] In reaction to suggestions that the U.S. launch a military offensive against the alleged terrorists' sanctuary in Yemen, The Washington Post noted that Yemeni forces equipped with U.S. weapons and intelligence had carried out two major raids against AQAP shortly before the bombing attempt, and that the terror group may have lost top leaders in a December 24, 2009 airstrike.[97] On March 24, 2011, the Associated Press reported that before Abdulmutallab set off on his mission, he visited the home of al-Qaeda manager Fahd al-Quso to discuss the plot and the workings of the bomb.[98] In addition, the AP said that Abdulmutallab targeted Detroit because the plane ticket there was cheaper than the tickets to either Houston or Chicago. This suggests that al-Qaeda in Yemen chose to attack "targets of opportunity," rather than Osama bin Laden's preference of "symbolic targets."[99] Jasper SchuringaJasper Schuringa, who was en route to Miami, Florida, for a vacation, stopped Abdulmutallab from causing too much damage and received burn injuries in the process. In a statement, Schuringa, who was in seat 20J on the flight, said he was able to locate Abdulmutallab, help to extinguish the fire that the explosive had caused, and helped to restrain Abdulmutallab using plastic cuffs.[23] Schuringa lives in Amsterdam, and was born in 1977 in Curaçao, Netherlands Antilles.[100] Schuringa is a graduate of Leiden University, Leiden. He is a film director of low-budget Dutch films for an Amsterdam-based media company, and was the assistant director for National Lampoon's Teed Off Too.[101] Dutch Deputy Prime Minister Wouter Bos phoned Schuringa on behalf of the Dutch government the day after the attack, and conveyed the government's compliments and gratitude for Schuringa's part in overpowering the suspect.[102] Dutch Member of Parliament Geert Wilders[103] called Schuringa "a national hero" who "deserves a royal honor", which Wilders said he would ask the Dutch government to award.[104][105] According to the Dutch newspaper De Volkskrant, Queen Beatrix expressed her feelings of gratitude towards Schuringa.[106] On May 21, 2010, Schuringa received the Honorary Medal of the city Amsterdam from then-acting mayor of Amsterdam, Lodewijk Asscher, for his "extraordinary heroism."[107] In December 2010, Schuringa was also awarded the Silver Carnegie Medal from the Dutch division of the Carnegie Hero Fund.[108] Reactions and investigationsU.S. response President Barack Obama was notified of the incident by an aide while on a vacation in Kailua, Hawaii, and spoke with officials from the Department of Homeland Security.[37] He instructed that all appropriate measures be taken in response to the incident.[109] The White House called the attack an act of terrorism.[42][110] While describing security measures taken by U.S. and foreign governments in the immediate aftermath of the attack, U.S. Secretary of Homeland Security Janet Napolitano said "once the incident occurred, the system worked." She cited "the actions of the passengers and the crew on this flight" to show "why that system is so important."[111] After heavy criticism, she stated the following day that the system "failed miserably," referring to Abdulmutallab's boarding the flight with an explosive device.[112] On December 29, President Obama called the U.S.'s failure to prevent the bombing attempt "totally unacceptable", and ordered an investigation.[113] The U.S. investigation was managed by the Detroit Joint Terrorism Task Force, led by the FBI and including the U.S. Customs and Border Protection, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, the Federal Air Marshal Service, and other law enforcement agencies.[114] They initially focused on determining what kind of training Abdulmutallab received, who else (if anyone) was in the same training program, whether others were preparing to launch similar attacks, whether the attack was part of a larger plot, whether the attack was a test run, and who, if anyone, assisted Abdulmutallab.[115][116] Additionally, investigators examining what information the U.S. government possessed before the attack, why its National Counterterrorism Center did not make a connection between the warning from Abdulmutallab's father, National Security Agency (NSA) intercepts of conversations among Yemeni al-Qaida leaders about a "Nigerian" to be used for an attack (months before the attack took place), and why the suspect's U.S. visa was not withdrawn.[50][117] Analysis of explosivesThe substance that the suspect tried to detonate was a combination of more than 80 grams (2.8 oz) of pentaerythritol tetranitrate (PETN), a crystalline powder that is often the active ingredient of plastic explosives, the high explosive triacetone triperoxide (TATP),[118] and other ingredients.[2] PETN is among the most powerful of explosives, and chemically resembles nitroglycerin.[119] The powder was analyzed by the FBI at Quantico,[120] and an FBI affidavit filed in the Eastern District of Michigan[15][121] reflected preliminary findings that the device contained PETN.[122] The authorities also found the remains of the syringe.[15][121] The suspect apparently carried the PETN onto the plane in a 6-inch (15 cm)-long[19] soft plastic container, possibly a condom, attached to his underwear. Much of the container was lost in the fire.[123] ABC News cited a government test indicating that 50 grams (1.8 oz) of PETN can blow a hole in the side of an airliner, and posted photos of the remains of Abdulmutallab's underwear and explosive packet.[19]  In a public test conducted by the BBC, the test plane's fuselage remained intact, indicating that the bomb would not have destroyed the aircraft, though it did show window damage that would likely have led to cabin depressurization. This test was undertaken at ground level, with zero pressure differential between the cabin and the surrounding environment. This was claimed to have no effect on the overall result of the test, which aimed to simulate the explosion at 10,000 feet (3,000 m). It was not demonstrated what would happen at a typical cruising altitude of between 31,000 feet (9,400 m) and 39,000 feet (12,000 m), where the pressure differential would have caused the fuselage to be under a far greater stress than at ground level.[124] Al-Qaeda member Richard Reid (the "Shoe Bomber") had tried to detonate 50 grams of the same explosives in his shoes during an American Airlines flight on December 22, 2001.[118][119] On January 7, 2010, James L. Jones, the National Security Advisor, said Americans would feel "a certain shock" when a report detailing the intelligence failures that could have prevented the attack would be released that day. He said that President Obama would be "legitimately and correctly alarmed that things that were available, bits of information that were available, patterns of behavior that were available, were not acted on."[125] On April 6, 2010, it was reported that President Obama had authorized military action to kill Anwar al-Awlaki, the Muslim cleric accused of being a Yemen-based al-Qaeda commander behind the plot.[83] Al-Awlaki was killed on September 30, 2011, as a result of a targeted drone strike. International responseGordon Brown, Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, said that the UK would take "whatever action was necessary". The day after the attack, British police searched a family-owned flat where Abdulmutallab had lived while in London.[126] Dutch counter-terrorism agency NCTb said that it had started a probe into where the suspect originated.[127][128] Dutch officials also said that they will now use 3D full-body scanning X-ray technology on flights departing to the U.S.,[129] despite protests from privacy advocates. Dutch officials said that security must take priority over the privacy of the individuals being scanned, but the scanners are not designed to compromise an individual's privacy, as the imagery resolution is only high enough to detect non-metallic objects under clothing, such as powdered explosives.[130] Members of the Second Chamber (Lower House) of the Dutch parliament demanded an explanation from Minister of Justice Hirsch Ballin, asking how the suspect managed to smuggle explosives on board, despite Schiphol's reportedly strict security measures.[131][132] The incident also raised concerns regarding security procedures at Nigeria's major international airports in Lagos and Abuja.[133] In response to criticism, Nigerian civil aviation officer Harold Demuran announced that Nigeria would also set up full-body scanning X-ray machines in Nigerian airports.[130] In response to the incident and to comply with new U.S. regulations, the Canadian government said it would install full body scanners at major airports. The first 44 scanners were planned to be installed at airports in Vancouver, Calgary, Edmonton, Winnipeg, Toronto, Ottawa, Montreal, and Halifax.[134] Other agenciesDelta Air Lines, which owned Northwest until all operations were merged into Delta on January 31, 2010,[135] said its Detroit group did not handle security for the flight.[36] It released a statement calling the incident a "disturbance," and saying that Delta was "cooperating fully with authorities".[136] Delta's CEO, Richard Anderson, said in an internal memo that "Having this occur again [after 9/11] is disappointing to all of us... You can be certain we will make our points very clearly in Washington."[137] In January 2010, ICTS International, a security firm that provides security services to Schiphol airport,[138] and G4S (Group 4 Securicor Aviation Security B.V.), another security firm, traded blame over the security oversight, as did authorities at Schiphol Airport, the Federal Aviation Authority, and U.S. intelligence officials.[138] According to Haaretz, the failure was twofold: An intelligence failure, as Obama stated, in the poor handling of information that arrived at the State Department and probably also the CIA from both the father of the would-be bomber and the British security service; and a failure within the security system, including that of ICTS.[138] AftermathCriminal charges and conviction On December 26, a criminal complaint was filed against Abdulmutallab in the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Michigan, charging him with two counts: placing a destructive device in, and attempting to destroy, a U.S. civil aircraft.[15] Abdulmutallab was arraigned and officially charged by U.S. District Court Judge Paul D. Borman later the same day at the University of Michigan Hospital.[139] On January 6, 2010, a federal grand jury indicted Abdulmutallab on six criminal counts including attempted use of a weapon of mass destruction and attempted murder. "Not guilty" pleas were entered on the behalf of Abdulmutallab at the hearing.[140][118] He faced his first court hearing, a detention hearing, on January 8, 2010.[141] When asked about his decision to prosecute Abdulmutallab in federal court rather than have him detained under the law of war, U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder defended his position, saying that it was "fully consistent with the long-established and publicly known policies and practices of the Department of Justice, the FBI, and the United States Government as a whole," and that he was confident that Abdulmutallab would be successfully prosecuted under the federal criminal law. Holder had originally been asked by U.S. Senator Mitch McConnell, as well as several others, about his choice.[142] On February 16, 2012, Abdulmutallab, who had pleaded guilty but remained unrepentant, was sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole.[35] He is currently incarcerated at the ADX Florence supermax prison, near Florence, Colorado. Effect on travelThe U.S. government did not raise the Homeland Security Advisory System terrorist threat level, orange at the time (high risk of terrorist attacks), following the attack.[20][25] The Department of Homeland Security enacted additional security measures for the remainder of the Christmas travel period.[37] The TSA detailed several of these measures, including a restriction on movement and access to personal items during the last hour of flight for planes entering U.S. airspace. The TSA also announced an increase of officers and security dogs at airports.[10] The U.S. also increased the installation and use of millimeter wave scanners in many airports as a result of the attack. Designed to detect explosive materials under clothing, the machines were initially deployed at 11 airports, including O'Hare International Airport in Chicago, beginning in March 2010. The TSA announced further plans to install 1,000 of the machines in other airports by the end of 2011. Prior to 2010, the U.S. had only 40 scanners across 19 airports. The government also said that it planned to buy 300 additional scanners in 2010 and another 500 in the following fiscal year, starting October 2010. It costs around an estimated $530 million to purchase the 500 machines and hire over 5,300 workers to operate them. However, the U.S. government has stated that being scanned is voluntary and that passengers who object to the process could choose to undergo a pat-down search or be searched with hand-held detectors.[143][144] Under new rules prompted by the incident, airline passengers traveling to the U.S. from 14 nations would undergo extra screening: Afghanistan, Algeria, Cuba, Iran, Iraq, Lebanon, Libya, Nigeria, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, and Yemen. The inclusion of non-Muslim Cuba on the list was criticized.[145][146] On December 28, Transport Canada announced that for several days it would not allow passengers flying to the U.S. from Canada a carry-on bag, with some exceptions.[147] British Airways said that passengers flying to the U.S. would only be permitted one carry-on item.[148] Other European countries increased baggage screening, pat-down searches, and random searches for passengers traveling to the U.S. A spokesperson for Schiphol Airport said that heightened security would be in place for "an indefinite period".[149] However, in spite of the extra measures said to have been put in place to prevent a follow-up attack, Stuart Clarke, a photoreporter from the British newspaper Daily Express, claimed to have smuggled a syringe containing fluid, which could have been a liquid bomb detonator onto another plane. On January 3, 2010, Clarke said he boarded a jet from Schiphol Airport bound for Heathrow Airport just five days after the Christmas Day attack, and that the airport appeared to have imposed no additional security, such as precautionary pat-downs which could easily have discovered the syringe which he claimed he kept in his jacket pocket throughout.[150] U.S. political falloutWhite House Press Secretary Robert Gibbs and Secretary of Homeland Security Janet Napolitano said several times on Sunday talk shows that "the system had worked", a statement that engendered some controversy.[36][151] The next day they retracted the statements, saying that the system had in fact "failed miserably."[151] According to Napolitano, her initial statement had referred to the rapid response to the attack that included alerts sent to the 128 other aircraft in U.S. airspace at the time, and new security requirements for the final hour of flight, rather than the security failures that allowed the attack to happen.[152] Napolitano had originally stated on This Week that "once this incident occurred, everything went according to clockwork" and that "once the incident occurred, the system worked".[111] The day after the attack, the U.S. House Homeland Security Committee and Senate Commerce, Science, and Transportation Committee both announced that they would hold hearings in January 2010 to investigate how the device passed through security, and whether further restrictions should be placed on air travel; the Senate hearings began on January 21.[12][121] Four days after the attack, Obama said publicly that Abdulmutallab's ability to board the aircraft was the result of a systemic failure that included an inadequate sharing of information among U.S. and foreign government agencies. He called the situation "totally unacceptable."[153] He ordered that a report be delivered detailing how some government agencies had failed to share or highlight potentially relevant information about the suspect before he allegedly tried to blow up the airliner.[154] Two days later Obama received the briefing, which included statements that information about the suspect had failed to cross agency lines, and that the failures to communicate within the U.S. government had led to the threat posed by Abdulmutallab not being known by certain agencies until the attack. Obama said he would meet with security officials and specifically question why Abdulmutallab was not placed on the U.S. no-fly list, despite the government having received warnings about his potential al-Qaeda links.[155] On January 27, 2010, an official from the U.S. State Department said that Abdulmutallab's visa was not revoked because federal authorities believed that it would have compromised a larger investigation. The official, Patrick F. Kennedy, said intelligence officials had told the State Department that letting Abdulmutallab keep his visa would allow for a greater chance of exposing the terrorist network.[156][157][158] Alleged subsequent plotOn May 7, 2012, American officials claimed that they had thwarted another Al Qaeda plot that would have targeted a civilian passenger plane not unlike Northwest Airlines Flight 253.[159] American officials stated that the attack would have involved a more sophisticated bomb, also planted in undergarments, and would have been deployed near the anniversary of the killing of Osama Bin Laden. Officials did not state whether any persons had been arrested or charged in their operation.[159] An American official told MSNBC that the bomb was received by American security personnel in April, "was never near a plane" and "never posed a risk." They speculated that the bomb might have been constructed by Ibrahim al-Asiri, who is accused of constructing the explosives used by Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab in 2009.[160] See also

References

External links

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Portal di Ensiklopedia Dunia