|

North Shore Branch

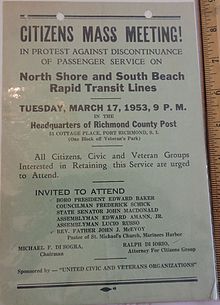

The North Shore Branch is a partially abandoned branch of the Staten Island Railway in New York City, which operated along Staten Island's North Shore from Saint George to Port Ivory. The line continues into New Jersey via the Arthur Kill Vertical Lift Bridge to Aldene Junction in Cranford. The line started construction in 1884, and rapid transit service on the line started on February 23, 1886. Passenger service on the North Shore Branch ended on March 31, 1953, although freight service continued to run along part of the North Shore Branch until 1989. In 2001, part of the line on the east end was reactivated for a short extension to Ballpark, which was in use from 2001 to 2010. In 2005, freight service on the western portion of the line was reactivated, and there are proposals to reactivate the former passenger line for rail or bus service. OperationTrains on the branch used tracks 10 through 12 at the Saint George Terminal. Trains originally consisted of two and three cars during the AM and PM rush hours, and one car at other times; by the end of passenger service, trains used only one car.[1] The fares on the branch were collected by the conductor on the train, who had to pull a cord, similar to how it was done with trolleys. The Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, which owned the branch, wanted to reduce service on the branch, and eventually abandon it. They purposely looked the other way when conductors skimmed money from the collected fares, allowing them to show a lower ridership to the Interstate Commerce Commission, and in return improve their chances for abandoning the branch.[2] Route description The North Shore branch of the SIRT began at Saint George Terminal, using the northernmost platform and tracks of the terminal.[3] After running through the St. George Freight Yard (near the modern Ballpark Station), the line ran on the shore of the Kill Van Kull from New Brighton to West Brighton. The line ran on land between St. George and New Brighton, and on a ballast-filled wood trestle supported by a wood retaining wall through Livingston and West Brighton. Though the right-of-way is distinguishable, little evidence of this portion of the line exists today, except for abandoned tracks and supports, much of which has eroded into the kill.[4][5] Beyond West Brighton near a NYCDEP water pollution control facility, the line rose onto a reinforced concrete trestle known as the Port Richmond Viaduct, crossing Bodine Creek and running for about a mile through the Port Richmond neighborhood.[6][7] West of Nicholas Avenue near Port Richmond High School, the line entered an open cut, crossing under the Bayonne Bridge approach and continued west to the Arlington Yard and station at South Avenue.[8] Rapid transit service continued via a northern spur to Port Ivory; freight service passed the current Howland Hook Marine Terminal (adjacent to Port Ivory) and crossed the Arthur Kill Vertical Lift Bridge to Cranford Junction in New Jersey.[9] The right-of-way from the Port Richmond Viaduct to Arlington Yard has remained intact and in good condition, though the former station sites and infrastructure are dilapidated and need rehabilitation or replacement should passenger service be reactivated.[10] History OpeningThe Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, operators of the SIRT until 1971, began construction on the line in 1884.[11] In order to build the North Shore Branch, property needed to be acquired along the North Shore of Staten Island. About 2 miles (3.2 km) of rock fill along the Kill Van Kull needed to be built to deal with opposition from property owners in Sailor's Snug Harbor.[12] In order to get property for the line to pass over the cove at Palmer's run, the company had to undergo a contest in litigation.[13][14] In Port Richmond, some property was acquired, displacing businesses and homes.[15] On the northwestern corner of Staten Island, the B&O purchased a farm and renamed it "Arlington"; the B&O built a freight yard on the farm by 1886.[15] The SIR was leased to the B&O for 99 years in 1885.[16][17] The proceeds of the sale were used to complete the terminal facilities at St. George, pay for 2 miles (3.2 km) of waterfront property, complete the Rapid Transit Railroad, build a bridge over the Kill Van Kull at Elizabethport, and build other terminal facilities.[18] The North Shore Branch opened for service on February 23, 1886, up to Elm Park cutting travel times to 39 minutes from an hour and a half via the ferry system.[13] The Saint George Terminal opened on March 7, 1886, and all SIR lines were extended to this station.[19][20] On March 8, 1886, the South Beach Branch opened for passenger service to Arrochar.[21] The remainder of the North Shore Branch to its terminus at Erastina was opened in the summer of 1886.[1] The new lines opened by the B&O railroad were called the Staten Island Rapid Transit Railway, while the original line from Clifton to Tottenville was called the Staten Island Railway.[11][22] In 1889–1890 a station was put up at the South Avenue grade crossing at Arlington in 1889–1890, where trains were turned on their way back to St. George.[23]  Various proposals were made by the B&O for a railroad between Staten Island and New Jersey. The accepted proposal consisted of a 5.25-mile (8.45 km) line from the Arthur Kill to meet the Jersey Central at Cranford, through Union County and the communities of Roselle Park and Linden.[15] Construction on this road started in 1889,[15] and the line was finished in the latter part of that year.[1] Congress passed a law on June 16, 1886, authorizing the construction of a 500-foot (150 m) swing bridge over the Arthur Kill, after three years of effort by Erastus Wiman.[24][25] The start of construction was delayed for nine months by the need for approval of the Secretary of War,[1][25] and another six months due to an injunction from the State of New Jersey.[25] This required construction to continue through the brutal winter of 1888[24][25] because Congress had set a completion deadline of June 16, 1888, two years after signing the bill.[25] The bridge was completed three days early on June 13, 1888, at 3 p.m.[26][25] At the time of its opening, the Arthur Kill Bridge was the largest drawbridge ever constructed in the world. There were no fatalities in the construction of the bridge.[25] On January 1, 1890,[1] the first train operated from Saint George Terminal to Cranford Junction.[27] Once the Arthur Kill Bridge was completed, pressure was brought upon the United States War Department by the Lehigh Valley Railroad and the Pennsylvania Railroad to have the newly built bridge torn down and replaced with a bridge with a different design, claiming that it was an obstruction for the navigation of the large numbers of coal barges past Howland Hook on the Arthur Kill. They were not successful in these efforts, however.[28] 1900s In 1905, Procter & Gamble opened a large plant near Arlington Yard, later called Port Ivory, resulting in additional traffic. The line's electrification project was completed on Christmas Day of 1925,[29][30] cutting ten minutes off of travel time from Arlington to Saint George.[31] In the 1930s, the SIRT began several projects to remove grade crossings along the formerly surface-level right-of-way, constructing the current concrete viaduct and open-cut sections of the line. On February 25, 1937, the Port Richmond–Tower Hill viaduct was completed, becoming the largest grade crossing elimination project in the United States.[32] The viaduct was more than 1 mile (1.6 km) long, and spanned eight grade crossings on the North Shore Branch of the SIRT. The opening of the viaduct marked the final part of a $6 million grade crossing elimination project on Staten Island, which eliminated 34 grade crossings on the north and south shores of Staten Island.[32] While the viaduct was being constructed, service on the branch was operated on one track.[33] With the opening of the viaduct, the stations at Port Richmond and Tower Hill reopened as elevated stations.[34] Arthur S. Tuttle, state director of the PWA, cut ribbons to dedicate the reopened stations, and rode over the 1 mile (1.6 km) of the viaduct and the 7 miles (11 km) of the route project in a two car train.[34] The project eliminated 37 grade crossings[34] including ones at several dangerous intersections and the 8-foot-high (2.4 m) crossing over Bodine Creek.[35] Around this time, the Lake Avenue and Harbor Road stations were constructed.[30] In the 1940s, freight and World War II traffic helped pay off some of the debt the SIRT had accumulated, briefly making the SIRT profitable. During the second World War, all of the east coast military hospital trains were handled by the SIRT, with some trains stopping at Arlington on Staten Island to transfer wounded soldiers to a large military hospital. The need to transport war material, POW trains, and troops, made the stretch of the Baltimore & New York Railway between Cranford Junction and the Arthur Kill extremely busy. The B&O also operated special trains for important officials such as Winston Churchill.[15] In 1945, SIRT purchased the property of the B&NY and merged it with the Staten Island Railway.[15][36] The line had been worked with B&O and SIRT equipment since it opened in 1890.[15] By 1949, there were no longer any staffed offices along the line except at Arlington. All of the stations on the line, with the exception of Harbor Road, Lake Avenue, Livingston and Snug Harbor, had waiting rooms and agents. The stations without waiting rooms were flag stops; the train would only stop if there was someone waiting at the station.[30] The station at Port Ivory, which was used for workers of the Procter & Gamble Plant and was only open for the morning and evening rush hour, closed around the year 1950.[30]  SIRT discontinued passenger service on the North Shore Branch to Arlington at midnight on March 31, 1953, along with service on the South Beach Branch. Passenger service had ceased because of city-operated bus competition, though the branch continued to carry freight.[1][37][38] The third rail on the line was removed by 1955.[39] On October 21, 1957, four years after North Shore Branch passenger trains ended, the very last SIRT special—a train from Washington carrying Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip to the Staten Island Ferry from a state meeting in Washington, D.C., with President Eisenhower—crossed the Arthur Kill Vertical Lift Bridge.[1][40] There was a royal train and a press train and they traveled over the Reading Railroad and the B&O to get to Camp Kilmer in New Jersey. Since British royalty was being transported, the movement was done in secrecy with high security. The trains reached the Camp by traveling via the Port Reading Branch of the Reading Railroad. In order to travel to Staten Island, which required traveling over the Arthur Kill swing bridge, the two trains had to be reconfigured. Done at the Camp, the two diesel locomotives in the front were dropped from the two consists, allowing the trains to pass over the bridge, which had a limited load capacity. Awaiting the return of the equipment from Staten Island, the two diesel trains were sent to Cranford Junction. On the morning of October 21, the press train, consisting of 10 cars, left the Camp in New Jersey and traveled to the SIRT via the Lehigh Valley Railroad. The royal train, which was constructed by Pullman Standard, followed an hour later. These two trains terminated at the Stapleton freight yard, which was cleaned up for the occasion.[1] Each of the trains were hauled back to Cranford Junction by a SIRT switcher after the Queen's motorcade left the yard. The trains, that afternoon, then went south to Baltimore.[15] Freight serviceIn November 1957, the Arthur Kill swing bridge was damaged by an Esso oil tanker, and was replaced by a state-of-the-art, single track, 558 foot vertical lift bridge in 1959.[41] The 2,000 ton lift span was prefabricated, then floated into place.[1] The new bridge was raised 135 feet and since the new bridge aided navigation on the Arthur Kill, the United States government assumed 90% of the $11 million cost of the project.[42] Freight trains started crossing the bridge when it opened on August 25, 1959.[43] The B&O became part of the larger C&O system through a merger with the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway. The freight operation on the island was renamed the Staten Island Railroad Corporation in 1971. The B&O and C&O became isolated from their other properties in New Jersey and Staten Island, with the creation of Conrail on April 1, 1976, by merger of bankrupt lines in the northeast United States.[41] As a result, their freight service was truncated to Philadelphia, however, for several years afterward, one B&O freight train a day ran to Cranford Junction, with B&O locomotives running through as well. By the year 1973, the Jersey Central's car float yard at Jersey Central was closed. Afterwards, the car float operation of the B&O was brought back to Staten Island at Saint George Yard. This car float operation was taken over by the New York Dock Railway in September 1979, and was ended the following year.[15] Only a few isolated industries on Staten Island were using rail service for freight, meaning that the yard at Saint George was essentially abandoned.[41] In April 1985, the Chessie System sold the railway to the New York, Susquehanna and Western Railway (NYS&W), a subsidiary of the Delaware Otsego Corporation (DO), for $1.5 million via a promissory note, and the NYS&W had hopes of attracting more customers to add profitability to the line.[1][37][44] In 1989, the NYS&W embargoed the right-of-way east of Elm Park on the North Shore Branch, ending all rail freight traffic to Saint George.[1] In 1990, Procter & Gamble, the line's primary customer, closed.[1] The closure resulted in a major decline in freight traffic, with the Arthur Kill bridge being removed from service in July 1991, and the final freight train was operated in April 1992.[1][45][46] Afterwards, the North Shore Branch and the Arthur Kill Bridge were taken over by CSX. The right-of-way was sold again in 1994, to the New York City Economic Development Corporation (NYCEDC), whose purchase was followed by a decade of false starts.[43] During the early 2000s, plans for reopening the Staten Island Rapid Transit line in New Jersey were announced by the New York Port Authority. Since the Central Railroad of New Jersey became a New Jersey Transit line, a new junction would be built to the former Lehigh Valley Railroad. In order for all New England and southern freight to pass through the New York metropolitan area, a rail tunnel from Brooklyn to Staten Island, and a rail tunnel from Brooklyn to Greenville, New Jersey were planned.[15] On December 15, 2004, a $72 million project to reactivate freight service on Staten Island and to repair the Arthur Kill Vertical Lift Bridge was announced by the NYCEDC and the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey.[43] Specific projects on the Arthur Kill Vertical Lift Bridge included repainting the steel superstructure and rehabilitating the lift mechanism.[43] In June 2006, the freight line connection from New Jersey to the Staten Island Railway was completed, and became operated in part by the Morristown and Erie Railway under contract with the State of New Jersey and other companies.[47] The Arthur Kill Vertical Lift Bridge was renovated in 2006 and began regular service on April 2, 2007, sixteen years after the bridge closed.[48] A portion of the North Shore Line was rehabilitated, and the Arlington Yard was expanded.[49] Soon after service restarted on the line, Mayor Michael Bloomberg officially commemorated the reactivation on April 17, 2007.[50] Along the remainder of the North Shore Branch, there are still tracks and rail overpasses in some places.[4][5] Possible reactivation for passenger serviceThe Regional Plan Association's A Framework for Transit Planning in the New York Region released in 1986 recommended extending the proposed Second Avenue Subway from Manhattan under Water Street to Staten Island via Liberty State Park in New Jersey. The line would have descended into bedrock at Pine Street, stop at South Ferry, and would have emerged under Liberty State Park in Communipaw, New Jersey with a transfer to the proposed Hudson–Bergen Light Rail. From there it would have run along the Jersey Central's line to Constable Hook, and then pass through a tunnel under the Kill Van Kull and connect with the North Shore Branch in New Brighton. They proposed several stops in Bayonne and Jersey City and a stop on Richmond Terrace. This 10 miles (16 km)-long line was estimated to take slightly less time than the Staten Island Ferry, but would result in passengers spending less time waiting and transferring.[51]: 155 The New York City Department of Transportation undertook a study called North Shore Transit Corridor, which proposed using the right-of-way as a guided busway, which would decrease travel times to and from St. George for bus routes from across the island. Specially equipped buses were to enter and leave the guideway at Howland Hook, Morningstar Road, Broadway or Bard Avenue, and operate nonstop to the ferry, or with a local stop near St. George. The study estimated that the guided busway would carry 12,000 passengers in the peak direction in the peak hour, compared to 9,000 for a regular busway, 18,000 for light rail, and 24,000 for heavy rail. The guided busway was estimated to cost $20.5 million to construct, lower than the $20.8 million estimate for the busway, and the $36 million and $38.5 million estimates for heavy rail and light rail, respectively.[51]: 152–154 A report completed by the New York City Department of City Planning (DCP) in 1991, which analyzed the potential use of inactive railroad rights-of-way for transit service, recommended that the North Shore Branch be reactivated for use by heavy rail in two phases. As part of the first phase, St. George would be connected with Arlington Yard, where an intermodal facility could divert express bus and car passengers that went to Manhattan via the Verrazzano-Narrows Bridge. The second phase would connect the yard with the New Jersey Transit system and the Travis Branch, providing alternate ways of getting to Manhattan and capturing the reverse commuter market from Staten Island to New Jersey. The DCP's Staten Island Reverse Commute UTMA Study projected 419 work trips from Staten Island to Woodbridge and Edison in New Jersey, and expected that number to increase if the line was extended using the Staten Island Railroad Company Line in New Jersey and the Amtrak Northeast Corridor.[51]: 157 That same year, the Revitalizing the Staten Island Railroad study was conducted by the New York Cross Harbor Railroad Terminal Corporation, which recommended restoring the line from St. George to Cranford in Union County, New Jersey, with connections at Elizabeth Arch for the Northeast Corridor and North Jersey Coast Line of New Jersey Transit.[51]: 156 In 2001, a few hundred feet of the easternmost portion of the North Shore Branch were reopened west to the Richmond County Bank Ballpark station to provide passenger service to the new Richmond County Bank Ballpark, home of the Staten Island Yankees minor-league baseball team.[52] This service was discontinued in 2010, but the tracks and station remain in place.[52] In 2003, Borough President James Molinaro and the Port Authority commissioned a study on the feasibility of rebuilding the North Shore line and restoring passenger service to St. George.[11] In a 2006 report, the Staten Island Advance explored the restoration of passenger services on 5.1 miles (8.2 km) of the North Shore Branch between St. George Ferry Terminal and Arlington station. The study needed to be completed to qualify the project for an estimated $360 million, but a preliminary study found that daily ridership could exceed 15,000.[53] Chuck Schumer, a senator from New York state, asked for $4 million in federal funding.[54] A similar study, performed in 2009, explored the possibility of expanding the Hudson Bergen Light Rail line over the Bayonne Bridge and along the West Shore (including the Travis Branch right-of-way), adding service to Staten Island Teleport and West Shore Plaza, and creating the possibility of a rail belt line around the island.[55] Mayor Michael Bloomberg included reactivation of the North Shore line in his 2009 campaign for mayor, and the MTA hired SYSTRA Consulting in 2009 to think of further options for the North Shore Line's right-of-way.[11] An approximately 1-mile (1.6 km) portion of the western end is used for freight service as part of the Howland Hook Marine Terminal transloading system called ExpressRail, which opened in 2007 and connects to the Chemical Coast after crossing over the Arthur Kill Vertical Lift Bridge. A smaller eastern portion provided seasonal service to the passenger station for RCB Ballpark, where the Staten Island Yankees play. This service operated from June 24, 2001 to June 18, 2010.[56] As of 2008, restoration was being discussed along this mostly abandoned 6.1-mile (9.8 km) line as part of the Staten Island light rail plan.[57] In 2012, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority released an analysis of transportation solutions for the North Shore, which included proposals for the reintroduction of heavy rail, light rail, or bus rapid transit using the North Shore line's right-of-way. Other options included transportation systems management which would improve existing bus service, and the possibility of future ferry and water taxi services. Bus rapid transit was the preferred option for its cost and relative ease of implementation, which would require $352 million in capital investment. The analysis evaluated the alternatives according to their ability to "Improve Mobility", "Preserve and Enhance the Environment, Natural Resources and Open Space", and "Maximize Limited Financial Resources for the Greater Public Benefit".[58] Since 2015, the MTA has been planning to utilize the old right-of-way for bus rapid transit.[59] The 2012 plans included the West Shore/Teleport extension, which would add seven new stations, including two new stops in the vicinity of the former Arlington terminal.[60] In July 2018, the MTA indicated that it was retaining a consultant to advise on an environmental impact assessment for the bus rapid transit line on the North Shore Branch.[61] Station list

Notes and referencesNotes

References

External links

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Portal di Ensiklopedia Dunia