|

Negative inversionIn linguistics, negative inversion is one of many types of subject–auxiliary inversion in English. A negation (e.g. not, no, never, nothing, etc.) or a word that implies negation (only, hardly, scarcely) or a phrase containing one of these words precedes the finite auxiliary verb necessitating that the subject and finite verb undergo inversion.[1] Negative inversion is a phenomenon of English syntax. Other Germanic languages have a more general V2 word order, which allows inversion to occur much more often than in English, so they may not acknowledge negative inversion as a specific phenomenon. While negative inversion is a common occurrence in English, a solid understanding of just what elicits the inversion has not yet been established. It is, namely, not entirely clear why certain fronted expressions containing a negation elicit negative inversion, but others do not. As with subject-auxiliary inversion in general, negative inversion results in a discontinuity and so is a problem for theories of syntax. The problem exists both for the relatively layered structures of phrase structure grammars as well as for the flatter structures of dependency grammars. Basic examplesNegative inversion is illustrated with the following b-sentences. The relevant expression containing the negation is underlined, and the subject and finite verb are bolded:

When the phrase containing the negation appears in its canonical position to the right of the verb, standard subject-auxiliary word order obtains. When the phrase is fronted, as in the b-sentences, subject-auxiliary inversion, (negative inversion) must occur. If negative inversion does not occur in such cases, the sentence is bad, as the following c-sentences illustrate:

The c-sentences are bad because the fronted phrase containing the negation requires inversion to occur. In contrast, the d-sentences are fine because there is no negation present requiring negative inversion to occur. TraitsNegative inversion has several traits. The following subsections enumerate some of them:

Fronted argumentsNegative inversion in the b-sentences above is elicited by a negation appearing inside a fronted adjunct. Negative inversion also occurs when the negation is (or is contained in) a fronted argument, but the inversion is a bit stilted in such cases:[2]

The fronted phrase containing the negation in the b-sentences is an argument of the matrix predicate, not an adjunct. The result is that the b-sentences seem forced, but they are nevertheless acceptable for most speakers. If inversion does not occur in such cases as in the c-sentences, the sentence is simply bad. AbsenceAn imperfectly-understood aspect of negative inversion concerns fronted expressions containing a negation that do not elicit negative inversion. Fronted clauses containing a negation do not elicit negative inversion:

The presence of the negations nothing and nobody in the fronted clauses makes one might expect negative inversion to occur in the main clauses, but it does not, a surprising observation. More surprisingly, certain adjunct phrases containing a negation do not elicit negative inversion:

A close examination of the fronted phrases in these sentences reveals that each is a depictive predication over the subject argument (an adjunct over the subject), as opposed to a predication over the entire main clause (an adjunct over the clause). The examples therefore demonstrate that negative inversion is sensitive to how the fronted expression functions within the clause as a whole. DistinctivenessThe most intriguing cases of negative inversion are those where the meaning of the sentence shifts significantly based upon whether inversion has or has not occurred:[3]

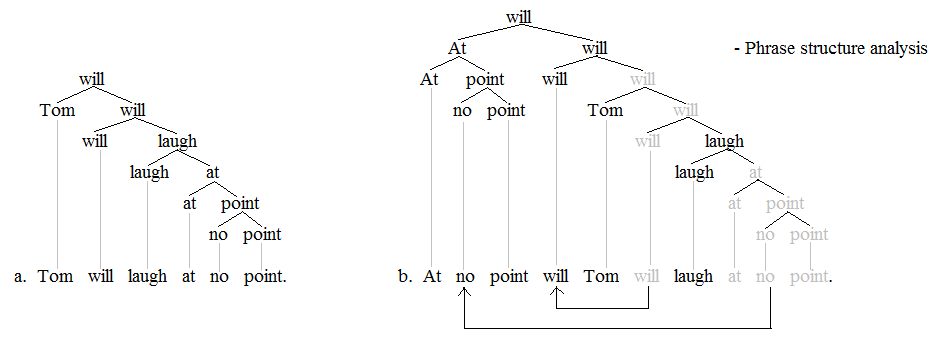

The paraphrases below the examples restate the meaning of each sentence. When negative inversion occurs as in the a-sentences, the meaning is much different than when it does not occur as in the b-sentences. The meaning difference is a reflection of the varying status of the fronted expressions. In the a-sentences, the fronted expression is a clause adjunct or argument of the main predicate, whereas in the b-sentences, it is a depictive predication over the subject argument. Structural analysisLike many types of inversion, negative inversion challenges theories of sentence structure. The challenge is because of the fronting of the phrase containing the negation. The phrase is separated from its governor in the linear order of words so a discontinuity is perceived. The discontinuity is present regardless of whether one assumes a constituency-based theory of syntax (phrase structure grammar) or a dependency-based one (dependency grammar). The following trees illustrate how this discontinuity is addressed in some phrase structure grammars:[4] The convention is used if the words themselves appear as labels on the nodes in the trees. The tree on the left has canonical word order. When the phrase containing the negation is fronted, movement (or copying) is necessary to maintain the strictly binary branching structures, as the tree on that right shows. To maintain the strictly binary and right branching structure, at least two instances of movement (or copying) are necessary. The following trees show a similar movement-type analysis, but this time a flatter, dependency-based understanding of sentence structure is now assumed: The flatter structure allows for a simpler analysis to an extent. The subject and auxiliary verb can easily invert without affecting the basic hierarchy assumed so only one discontinuity is perceived. The following two trees illustrate a different sort of analysis, one where feature passing occurs instead of movement (or copying):[5] The phrase structure analysis is on the left and the dependency structure analysis on the right. The analyses reject movement/copying, and in its stead, they assume information passing (feature passing). The nodes in red mark the path (chain of words, catena) along which information about the fronted phrase is passed to the governor of the fronted expression. In this manner, a link of a sort is established between the fronted phrase and the position in which it canonically appears. The trees showing movement/copying illustrate the analysis of discontinuities that one might find in derivational theories such as Government and Binding Theory and the Minimalist Program, and the trees showing feature passing are similar to what one might find in representational theories like Lexical Functional Grammar, Head-Driven Phrase Structure Grammar, and some dependency grammars. See alsoNotes

Literature

|

Portal di Ensiklopedia Dunia