|

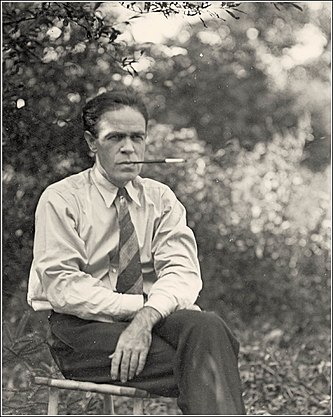

Milo Hastings

Milo Milton Hastings (June 28, 1884 – February 25, 1957) was an American inventor, author, and nutritionist. He invented the forced-draft chicken incubator and Weeniwinks, a health-food snack. He wrote about chickens, science fiction, and health, among other things. Some of his writing is available in book form and on Project Gutenberg. Hastings was married twice and had three children. WriterBorn in Farmington, Atchison County, Kansas, Hastings wrote all his life. His books covered a broad range of topics: chicken husbandry (The Dollar Hen), science fiction (City of Endless Night), nutrition (Physical Culture Cook Book), health (High Blood Pressure). Hastings spent the bulk of his professional life as the food editor for Bernarr Macfadden writing hundreds of columns on food and nutrition for Physical Culture magazine. Hastings contributed several entries to The Olympian System, a four volume set of books published by Macfadden to promote his notions of “developing physical and mental efficiency.” When Macfadden started the New York Graphic newspaper Hastings wrote a series of articles on "Food, Health, and Happiness". Hastings wrote on other topics as well: commerce (The Egg Trade of the United States), philosophy (an introduction to Brann The Iconoclast), urban planning (promoting the linear city idea of Edgar Chambless), social commentary (the stage play Class of ’29), and an occasional short story ("The New Chivalry"). Hastings writing was infused with both clarity and wit. Complex ideas became simple. Historical, biblical, and cultural references were frequent. He got interested in many things over a lifetime. Where his interest led, he would learn, then write, and then move on. Clutch of the War-GodThree of Hastings’ science fiction works are known to survive: In the Clutch of the War-God (1911), The Book of Gud (with Harold Hersey, 1919), and City of Endless Night (1920). There may be others serialized in a Bernarr Macfadden publication, as was the case with Milo’s known works. Clutch of the War-God was serialized in three parts in the July, August, and September 1911 issues of Physical Culture magazine. It was never published in book form. What is known of the origin of Clutch comes from the Sam Moskowitz article “Bernarr Macfadden and His Obsession with Science-Fiction” that appeared in Fantasy Commentator in 1986. Macfadden at the time (1910) was under a suspended jail sentence for an obscenity conviction related to a beauty contest. He commissioned Milo to write a futuristic fiction story promoting his (Macfadden’s) views on physical health and scolding the federal government, hoping to shame officials into granting him a pardon. Macfadden wrote a signed introduction to the story:

The story is subtitled “The Tale of the Orient’s Invasion of the Occident, as Chronicled in the Humaniculture Society’s ‘History of the Twentieth Century.’” Japan has a superior society and government but suffers from food shortages and excess population. They go to war with the United States successfully invading the central states with airplanes transported across the Pacific on flat-topped ships. Here is an excerpt:

Some predictions in Clutch are remarkably accurate. Modern aircraft carriers are anticipated as is industrial agriculture. As a polemic the story served to further antagonize the government against Macfadden. Milo continued to write for Macfadden for years to come. The Book of GudIn 1919, Hastings and Harold Hersey, editor of the pulp The Thrill Book, collaborated on a short science-fiction novel, The Book of Gud, with mutual friend, Billy Rose, previewing (and dismissing) the chapters as they came forth.[2] It was eventually published in Hersey's magazine, Main Street, issue of July 1929, although Hastings' byline was changed to the pseudonym, Dan Spain. The story "... deals with a god in whom nobody believed, and of his adventures the day after eternity." City of Endless NightThe science fiction work for which Hastings is best known is City of Endless Night, a dystopian work. It first appeared as the story "Children of Kultur" serialized in True Story Magazine in seven installments from May to November, 1919. The word kultur, German for culture, had been made infamous by Allied propaganda in World War I. After Woodrow Wilson’s reelection in 1916 there was a concerted effort on the part of his administration to convince the citizenry to go to war. A Committee on Public Information was established that produced pro-war and anti-German propaganda. There were pamphlets with titles such as “The German Whisper” and “Conquest and Kultur”. There were movies with titles like The Kaiser, the Beast of Berlin and “Wolves of Kultur”.[3]  "Children of Kultur" was later revised, retitled City of Endless Night and published by Dodd, Mead and Company, Inc., copyright 1919, 1920. It was reprinted in 1974 by Hyperion Press, Inc. with an introduction by Sam Moskowitz who edited a reprint series of two dozen science fiction classics for Hyperion. Here is an excerpt from his introduction putting the work in its place in the development of science fiction:

City of Endless Night was written as World War I was ending and anticipates the resurgence of Germany and the rise of fascism. City of Endless Night is one of the works cited in an article on “Literary Propheteering” by Murray Teigh Bloom that appeared in the February 1, 1941 Saturday Review of Literature:

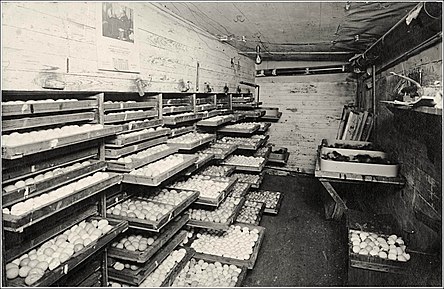

Some say that City of Endless Night was the original inspiration for Fritz Lang’s 1927 science fiction film Metropolis.[4] Chicken husbandryHastings’ interest in chickens began as a teenager on his family’s farm. In college at Kansas State Agricultural College he began their poultry husbandry program.[5] He built a new kind of chicken house based on plans from the Maine Experiment Station. It was a “curtain-front” house, the idea being a big frame covered with heavy white cloth on the south side instead of glass windows. The cloth let the water vapor pass through to keep the house drier, but was as warm as glass. In 1904 while still at Kansas State he began the first official egg laying contest in America.[6] It was during his college days he got the idea for the forced-draft chicken incubator. The goal was to incubate eggs in large numbers. Up to that time eggs were incubated by the dozens. Milo’s goal, later appearing on his stationery, was the million egg incubator. The technical problem was the control of heat and humidity. Eggs in the early stages of incubation take in heat. In the later stages they give off heat. Milo’s idea was an incubator with eggs in various stages of incubation with a fan to move the excess heat of the later stages to the earlier stages all while maintaining the proper humidity. He proposed the idea to the Department of Agriculture where he was working after he completed college in 1906. The idea was rejected as impractical. The Department did accept his 1909 patent (Serial No. 911,875) for a cold-storage evaporimeter. Hastings recognized the importance of maintaining proper humidity in the cold storage of eggs. He wrote Circular 149, "A Cold-Storage Evaporimeter", describing the device and Circular 140 on "The Egg Trade of the United States." In 1909 while still working for the Department (he left in 1910) he wrote The Dollar Hen, which became the classic guide to free-range chicken farming. The book was published in 1911 by the National Poultry Publishing Company. It was republished in 2003 by Norton Creek Press and is also available on the Internet through Project Gutenberg. The book is full of practical advice and Hastings’ witticisms:

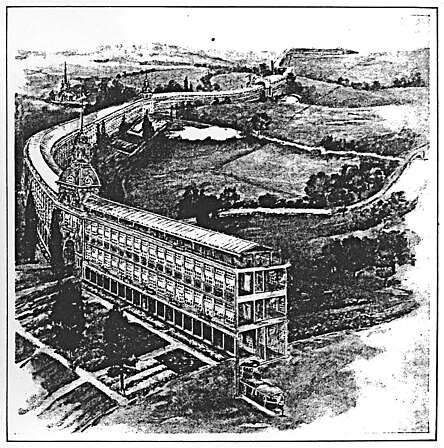

Hastings’ serialized portions of The Dollar Hen as “Home Course in Poultry Keeping”. The series was distributed by the American Press Association and appeared in several papers in 1910 and 1911.  Hastings made three tries at building a large commercial forced-draft chicken incubator. In 1911 he built a 6000 egg incubator in Brooklyn, New York, for a Walter B. Davis. An advertising booklet “Davis Poultry Farm” described operations on the farm. Later in 1911 Hastings went to Muskogee, Oklahoma and built a 30,000 egg incubator in a business arrangement with a Lieber, a local lawyer and business man. In the spring of 1912 Milo went to Petaluma, California, then the chicken capitol of the West, trying to generate interest in a million egg incubator. With interest lacking he then went to Port O’Conner, Texas and built a 150,000 egg incubator with financial support from a local businessman. All these business ventures were undercapitalized and none were a commercial success. While still working on the Brooklyn incubator, Milo filed for a patent, Serial No. 624,885 for “A Hatchery for the Eggs of Domestic Fowl”. (The application was witnessed by Edgar Chambless, Hastings' urban planning mentor.) Supporting documents were filed in July, 1911 and further amended by counsel on May 24, 1912. The patent was rejected, the rejection appealed, and on Dec 30, 1912 the appeal was rejected. The patent application was eventually abandoned. In 1918 a Smith got patent Serial No. 1,262,860 for basically the same invention. The Smith patent was challenged in both the United States and Canada. The matter was in the courts for years. At first the challenges were unsuccessful. Then a new strategy was tried: that the Smith patent was invalid because of Hastings’ prior art. So Hastings had a career as an expert witness. This was the only money he ever made off his incubator invention. The matter wound up in the Supreme Court and was decided in Smith v. Hall, 301 U.S. 216 (1937). The decision, confirming Milo’s prior art, was writing by Justice Harlan Stone, soon to become chief justice. The decision tracks the evolution of Milo’s incubator ideas and his whereabouts. Hastings was also interested in industrializing the raising of chickens. In a Scientific American of September 18, 1915 he detailed how to raise poultry on a manufacturing basis. Hastings’ final major poultry activity was raising chickens at his place in Tarrytown, New York. By 1928 he had 10,000 birds selling the eggs in New York City. Then in 1929 a chicken cholera epidemic wiped the flock out in a matter of weeks. Milo discusses this disease in The Dollar Hen. His discussion of its deadliness is all too prophetic. WeeniwinksHastings’ interest in healthy eating and his proclivity as an inventor lead to his creation of “Weeniwinks” in the early '30s. The idea was to create a processed food as a snack for kids that would be good for them. That meant the ingredients were based on natural grains and no sugar. At the time such a product did not exist. Milo tried many mixtures of ingredients before hitting on a promising combination of wheat and corn. He used his young children and their friends as taste testers.  The technical problem to be solved in the manufacture of the product was how to cook the ingredients without their sticking to the mold. Milo tried several possibilities and wound up using ordinary cast iron. The development of the product was done in his compound in Tarrytown, New York where a pilot plant was built. For bulk production a factory was built on the family farm in Effingham, Kansas. With the deepening of the Great Depression the monies to continue the venture were not forthcoming and the factory was abandoned. Later in 1938 Hastings tried to promote the idea in Russia.[7] A test-tube filled with Weeniwinks remains in the memorabilia of one of Hastings’ sons. Urban planningAnother long-time interest of Hastings was urban planning and the linear city of Edgar Chambless. Hastings met Chambless in 1909 and they remained lifelong friends. Hastings lived with Chambless briefly early in their acquaintance and Chambless would entertain Hastings’ children later on.  Chambless presented his ideas in his 1910 book Roadtown. Hastings wrote magazine articles based on the same ideas for The Independent (May 5, 1910) and Sunset, The Pacific Monthly (January, 1914). Hastings entered a competition for "The Best Solution of the Housing Problem," sponsored by the American Institute of Architects and the Ladies' Home Journal. His entry, "A Solution of the Housing Problem in the United States", was awarded one of the two top prizes and printed in the Journal of the American Institute of Architects (June, 1919), the Ladies’ Home Journal (January, 1919), and The Joke About Housing.[8] The Harvard Design School Library[9] retains an extensive collection of material about Roadtown. The goal of Roadtown was to reinvent housing according to principles of greater efficiency. The essential idea was a continuous linear house owned by the occupants with farmland on either side and the utilities beneath. Here is an excerpt from Milo’s Sunset article providing some of the details:

The Roadtown idea has a utopian aspect. The drawings and text almost read like science fiction. Chambless acquired rights to some of the patents needed to implement the concept. In particular, Thomas A. Edison contributed his cement pouring patents needed to construct the buildings. Chambless proselytized for his Roadtown concept for decades until the end of his life in 1936. Hastings had by then moved on to other things. Broadway connection Though a prolific writer Hastings never learned to touch-type. This led to a never-ending search for typing help. That was how he came to be friends with William Samuel Rosenberg, later notable as Broadway impresario Billy Rose. Rosenberg had been trained in Gregg Shorthand by John Robert Gregg himself and at age 16 had won a high-speed dictation contest. On the train between New York and Washington Milo would dictate and Billy would record. In the 1920s, when Billy began to write songs, Milo suggested the stage name “Billy Rose”.[10][citation needed] In the early 1920s Hastings penned The Who-Ams, a comedy-drama, with Leslie Burton Blades. Evidently the play was never produced. A copy exists in the archives of the New York Public Library Performing Arts Theatre. Hastings was also acquainted with Ned Wayburn the head of the Ned Wayburn Studios of Stage Dancing. Family lore holds that much of Wayburn’s 1925 book The Art of Stage Dancing was actually written by Hastings. In 1936, during the Great Depression, Hastings and Orrie Lashin (secretary to Walter Lippmann) wrote the play Class of ’29 under the auspices of the Federal Theatre Project. The play is about the spiritual unrest of college graduates unable to find work during the Depression. Heywood Broun devoted one of his "It Seems to Me" columns in a March 1936 to accusations that the play was socialist propaganda. The play enjoyed a brief run at the Manhattan Theatre on Broadway in the spring of 1936[11] and was presented in other US cities. Family Milo Milton Hastings was the youngest of the seven children of Reverend Zachariah Simpson Hastings and Rosetta (Butler) Hastings. Each of the children had double initials. "This happened so with the two first, with the others it was purposed so."[12] His father was a preacher and farmer in Kansas where the family was raised. Only four of the boys survived to adulthood. Brother Paul P. Hastings became the VP of traffic for the Santa Fe Railroad. Milo's mother's father was Pardee Butler, an abolitionist preacher who came to Kansas before the Civil War and is remembered in Kansas history for being set adrift on the Missouri River for his beliefs.[13] After the Civil War the family became involved with the temperance movement and anti-smoking campaigns. Milo rebelled against his family's religious beliefs, although his writing is sprinkled with biblical references. Milo married Beatrice Hill in 1906. They soon separated and were divorced in 1913 after he had his first child by Carmen Horowitz (née Frances Horowitz.) He married a second time in 1916 to Sybil Butler, a first cousin, and had two more children. There are three grandchildren and one great-grandchild. After living many places in his youth, Hastings bought an old quarry in Tarrytown, New York in 1920 and lived there until his death in 1957. The quarry was given to the town of Tarrytown and is now a park. Milo is buried with some of his family in the Pardee Cemetery in Cummings, Atchison County, Kansas. Notes

Bibliography

External links

|

Portal di Ensiklopedia Dunia