|

Military organization of the Germanic peoples

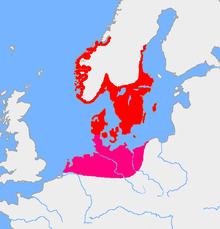

By military organization of the Germanic peoples is meant the set of forces that made up the armies of the Germanic peoples, including the organization of their units, their internal hierarchy of command, tactics, armament and strategy, from the Cimbrian Wars (late 2nd century B.C.) to the Marcomannic Wars (mid-3rd century A.D.). After this period a whole series of confederations of peoples (from the Alemanni to the Franks, Goths, and Saxons) were generated, each with its own internal military organization, which will be analyzed individually and separately. Historical contextOrigins In ancient times there was a widespread hypothesis, reported by Publius Cornelius Tacitus, in De origine et situ Germanorum, that the Germani were an indigenous people of Germania itself.[1] Again according to the Roman historian, they considered themselves descendants of Tuisto, deity of the land, from where his grandchildren, offspring of his son Mannus, would be the progenitors of the three Germanic lineages: that of the Ingaevones, the Istvaeones and the Irminones. According to other traditions, however, Tuisto's sons were more numerous, having thus given rise to other tribes: the Marsi, Suebi, Gambrivii, and Vandals.[2] According to modern archaeological research, the Germani would constitute the result of Indo-Europeanization, of the first half of the third millennium B.C., in southern Scandinavia and Jutland by people from central Europe, which had already been Indo-Europeanized during the fourth millennium B.C.[3] By the mid-eighth century B.C., the Germani are attested along the entire coastal strip from Holland to the mouth of the Vistula. The pressure continued in the following centuries, not as a unified, unidirectional movement but as an intricate process of advances, retrogressions, and infiltrations into regions also inhabited by other peoples. Around 550 BCE they reached the Rhine area, imposing themselves on the pre-existing Celtic peoples[4] and partly mixing with them (the border people of the Belgae are considered mixed). From the 5th to the 1st century BC, during the Iron Age, the Germani pressed steadily southward, coming into contact (and often conflict) with the Celts and, later, the Romans. In the area of contact with the Celts, along the Rhine, the two peoples came into conflict. Although possessing a more articulated civilization, the Gauls suffered the settlement of Germanic outposts in their territory, which gave rise to overlapping conflicts between the two peoples: settlements belonging to one or the other of these two peoples alternated and penetrated, even deeply, into their respective areas of origin. In the long run, the Germani, who would spread west of the Rhine a few centuries later, emerged victorious from the confrontation. An identical process would occur, to the south, along the other natural embankment to their expansion, the Danube.[5] Germani and Romans (late 2nd century B.C.-mid 3rd century A.D.). The Germani came into contact with Rome from the latter part of the 2nd century BC, with the incursions of the Cimbri and Teutons into Roman territory. The two Germanic peoples moved from Jutland and penetrated Gaul, pushing first into Pannonia, then into Noricum (where they beat a Roman army at Noreia in 113 BC), and finally into the newly established Roman province of Gallia Narbonensis. However, the raids continued for about a decade until, after some failures on the part of the Roman generals who rushed to stop them, the intervention of the consul Gaius Marius was necessary. The two Germanic populations were annihilated in two separate battles at Aquae Sextiae (102 B.C.) and Vercellae (101 B.C.). Rome was now safe from a possible Germanic invasion. At the time of the conquest of Gaul led by Caesar (58-50 BC), new conflicts flared up along the Rhine, the border between the Celts and the Germani. Since 72 B.C., a group of Germanic tribes, led by the Suebi of Ariovistus, had crossed the river and harassed Gallic territory with their raids, even inflicting a severe defeat on the Gauls near Amagetobria (60 B.C.). It seems that Ariovistus had crossed the Rhine together with the Suebian peoples from the valleys of the Neckar and Main rivers.[6] The Gauls then invoked the help of Caesar, who finally defeated Ariovistus near Mulhouse (58 B.C.).[7] However, the defeat of Ariovistus[8] was not enough to stop the pressure exerted by the Germanic peoples on the Gauls in those years. A few years later Caesar was also able to build a bridge over the Rhine and cross it, bringing devastation to the German territories east of the river during two different campaigns in 55[9][10] and 53 BCE.[11] The story goes that driven from behind by the pressure of the Suebi, the Germanic tribes of the Usipetes and Tencteri had wandered for three years, and had pushed on from their territories, north of the Main River, until they reached the regions inhabited by the Menapii at the mouth of the Rhine.[9] Having defeated the two tribes in Belgic Gaul,[12] the Roman proconsul had penetrated into the lands of the Germani.  Having crossed the Rhine, he carried out raids and looting to terrorize the enemy and induce him to renounce new incursions into Gaul.[10] Caesar, by repelling the Germanic peoples across the Rhine during these years, had in fact transformed this river into what would be one of the most important natural barriers of the Empire for the next four to five centuries. It had, therefore, not only stopped the migratory flows of the Germani, but also saved Celtic Gaul from the Germanic danger, thus giving Rome, which had won the war, the right to rule over all the peoples in its territory.[13] The Germanic peoples apparently remained calm for about twenty-five years, while in 38 B.C., the Germanic "client" population of the Ubii was moved into Roman territory. In 29 B.C. a new Suebi incursion again brought devastation to the eastern part of Gaul; again in 17 B.C., a coalition of Sicambri, Tencteri, and Usipetes caused the defeat of the Roman proconsul Marcus Lollius and the loss of the legionary insignia of legio V Alaudae. It was as a result of these advents that the Roman Emperor Augustus, who traveled to Gaul in 16 B.C. with his adopted son, Tiberius, felt it was time to permanently annex Germania Magna (as Caesar had done with Gaul), bringing the "natural" borders of the Roman Empire further east, from the Rhine River to Elbe. The actual campaigns began in 12 B.C. by Augustus' stepson, Drusus the Elder,[14] who led the Roman armies until they occupied much of the territory between the Rhine and Weser rivers, although in 9 B.C. he died prematurely.[15]  New Roman operations were undertaken in Germania in the following years, taking the imperial borders as far as the Elbe, mainly through the leadership of the future Emperor Tiberius, who succeeded in permanently occupying all Germanic territories west of the river,[16] with the sole exception of Bohemia in its southern part.

It was necessary, therefore, to annex the powerful Marcomanni kingdom of Maroboduus as well. Tiberius was thus prepared to attack even the last bastion of free Germania (in 6 A.D.),[17][18] moving simultaneously with two armies (one from Mogontiacum and the other from Carnuntum), and converging on Bohemia.[19] The Roman armies were stopped, however, by the outbreak of revolt in Pannonia and Dalmatia.[20] All the territories conquered in this 20-year period were compromised when in the year 7 Augustus sent Publius Quinctilius Varus to Germania, who lacked diplomatic and military skills, as well as being unaware of the people and places. In 9 an army of 20,000 men consisting of three legions and a dozen auxiliary units was massacred in the forest of Teutoburg by Arminius, a Roman citizen of Germanic origin. As luck would have it, Maroboduus did not ally himself with Arminius, and the assembled Germani stopped before the Rhine, where only 2 or 3 legions remained to guard the entire province of Gaul.[21] The military campaigns that followed by the Romans (A.D. 10 to 16), first under the high command of Tiberius and then of the heir-designate, Germanicus, were aimed both at averting a possible Germanic invasion and at preventing possible uprisings among the populations of the Gallic provinces.  Eventually Tiberius, having become emperor himself, preferred to suspend all military activity across the Rhine, leaving the Germanic peoples themselves to settle it by fighting each other. He only made alliances with some peoples against others, so as to keep them always at war with each other;[22] avoiding having to intervene directly, with great risk of incurring new disasters such as that of Varus;[23] but above all without having to employ huge military and economic resources, in order to maintain peace within the "possible and new" imperial borders. It is said that in 18 Arminius, having grouped under his command numerous Germanic tribes (such as Lombards, Semnones, and some of the Suebian lineages of the kingdom of Maroboduus), waged war on the Marcomanni kingdom of Maroboduus. And contrary to ancient Germanic traditions, both Germanic commanders, now accustomed to following Roman tactics, having both served for years in Roman auxiliary troops, faced each other in an orderly manner and with tactics unusual to them. Tacitus relates that:

Tiberius replied to him that he would not intervene in internal affairs of the Germanic peoples, since Maroboduus had remained neutral, when in 9, Augustus had requested his military aid in vain after the defeat of Varus. Maroboduus was thus forced to seek asylum from the emperor Tiberius, who accepted him, allowing him and the remnants of his court to take up residence in Ravenna, where he died a full 18 years later, in 36 or 37.[24] The following year, in 19, Arminius was assassinated by his subjects, who feared his growing power:

The next sixty years saw relative peace reign along the borders of the Roman Empire and Germania Magna. The client system created by Tiberius gave Rome a period of relative peace, at least until the Batavian revolt of 69-70. Then under Vespasian[25] and Domitian, the Romans again advanced into Germania, albeit in a marginal area called Agri Decumates (between the Rhine and the Danube, with the purpose of joining Mogontiacum with the Danube near Castra Regina).[26] The Roman client system began to enter a crisis towards the end of the first century, between 89 and 97, when Pannonia was the scene of a war against the Suebian peoples of Marcomanni and Quadi, and Sarmatian peoples of the Iazyges of the middle course of the Danube.[27] This was the first important sign of what would later prove to be the beginning of a long series, first of invasions for raiding purposes (late 2nd century),[28] and then of migrations of entire populations (from the 3rd century onward), by the Germanic tribes gravitating along the Danubian and Rhine limes in the following centuries. During this long period, the last attempt by the Romans to conduct offensive warfare in barbarian territory occurred under Emperor Marcus Aurelius, with the temporary occupation of Marcomannia (around 175).[29] Then came the slow and unstoppable decline, until the final collapse of the Western Roman Empire under the constant pressure of the Germanic peoples, now confederated into Alemanni, Franks, Goths and Saxons. Unit structureInfantrySince Caesar's time, the normal deployment of Germanic infantry (in this case those of the Suebi of Ariovistus) was phalanx-like, as Caesar himself recounts:

All this is confirmed by the Latin historian Tacitus in his Germania (late 1st century CE), according to whom the Germanic peoples, unlike the Celts, fought mainly on foot, in "wedge" phalanx formation.[30] From the nomadic tribes of the steppes (Scythians and Sarmatians) they later learned a greater use of horse at the expense of infantry.

The backbone of the Catti army was the infantry, which fought with slow actions but firm courage.[31] CavalryCaesar further recounts how the German horsemen (at least the peoples just east of the Rhine) fought normally. From this techno-tactical form, it is believed that the so-called equitate cohorts were later established at the time of the Augustan reform of the Roman army:

The Tencteri especially excelled in mounted combat, on a par with the Catti in infantry.[32] MercenariesTacitus relates that when the tribe among whom one lives is in a long period of peace, leaving its warriors to live in idleness, many young men of the nobility spontaneously go to other peoples, who at that time are engaged in war, and fight a war that is not their own. This happens because the Germanic peoples are a race that is intolerant of peace, and also because one acquires glory only in the midst of danger, and only with war can one maintain a large following. Only by war and raids can one obtain the means to be liberal and equitable.[33] NavyAmong the Germanic peoples of the first century CE, the Swedes of the Baltic Sea had powerful fleets. The shape of their vessels differed from other ones, however, in that at both ends the prow gave access to the front of the landing place. They did not have either ships with sails or oars lined up at the sides. The oars, on the contrary, were free as when sailing down a river. They rowed either on one side or the other as needed.[34] Organization and internal hierarchy According to Tacitus, the Germani grow naked and filthy until they attain the solidity of limbs and size of their bodies that arouse the wonder of their adversaries, such as the Romans. Servants cannot be distinguished from masters by any particular upbringing. Both grow up in the same environments, until age separates the free and the valor sets them apart.[35] The fundamental structure of Germanic society was the clan (Sippe), formed by the union of several related patriarchal families. The clan constituted an entirely autonomous and self-sufficient military (in infantry and cavalry formations) and political entity. Next to the combatants stand their loved ones, so close that they hear the screams of women and the wails of children.[36] The clan leaders gave rise, probably already in very ancient times, to periodic assembly meetings. The higher entity of the Sippen was the "people" (gau or pagus, called civitas by the Romans), that is, a tribe settled in a given territory. Essentially democratic, Germanic society experienced forms of elective monarchy[37] within which the assembly of free men (allthing or witan) periodically assembled retained de facto all powers, including judicial power. The assemblies expressed the decisions of the people, which thus consisted of the free and voluntary union of different clans. In case of war the assembly appointed army commanders[37] (whom Caesar called communis magistratus),[38] men of special valor or authority, often fighting at the head of their own ranks;[37] and these, mere "first among equals," were always made accountable to the assembly itself. It was only in later times that elected military commanders began to take on connotations more and more similar to kings (although Caesar in the mid-1st century B.C., had already called Ariovistus rex Germanorum),[39] and with the formation of the Romano-Barbarian kingdoms, after the end of the Western Roman Empire, prestigious royal lineages were established. In any case, the figures of the Germanic rulers at the head of their armies were always limited in their power by the assembly. Even valiant young men or those of distinguished nobility were in some cases given the powers of a chief. Tacitus relates that in the same retinue there was a hierarchy of ranks, distributed according to the decision of its leader; the subordinates competed with each other to emulate their leader and occupy the rank closest to him; the chiefs in turn, competed to have as numerous, valiant, and strong comrades as possible.[40] When it comes to battle, it was disgraceful for a leader to allow himself to be surpassed in valor by subordinates, but so was it for the latter not to match their commander in courage. It was also ignominious to save oneself from combat when the leader was killed, since it is the duty of subordinates to protect him, even attributing their own heroic deeds to him.[41] Tactics and weaponryWeaponryTacitus reports that iron in Germania Magna was scarce, even at the end of the first century, as could also be inferred from the type of their weapons. Few in fact seem to have made use of swords or large spears. Instead, they wielded the spears they called framea, with a narrow, short head, but so sharp and easy to wield that the same weapon served, depending on the circumstances, for hand-to-hand or ranged combat.[42] The mounted warriors also carried shield and spear; the foot soldiers threw many projectiles, and hurled them over great distances; they fought naked or at most lightly dressed in a light tunic. The Germani had no affectation or elegance. They merely adorned their shields with peculiar colors.[43] Few of them wore armor, only one or two (out of 100) wore helmets of metal (cassis) or leather (galea).[44] Tacitus also tells of the distant populations near the Baltic Sea of the Goths, who used instead, along with the Rugii and Lemovii, round shields and short swords.[45] Deployment and combat  The Germani had a "battle cry" called barditus by Tacitus:

According to Tacitus, judging from the whole, the backbone of the army of the Germani lies in the infantry, where the infantrymen are mixed with the horsemen, so that they are well adapted to the cavalry battles, and the speed of the infantry soldiers, chosen from among the young men and destined for the front of the deployment, is harmonized.[47] The army deployed to battle is arranged in a wedge.[48] Tacitus then further adds that:

Tacitus adds that alongside the ranks of fighters, stand in the rear their families, so close that they hear the cheering cries of their women and children. These are for every soldier the dearest people, whose wounds are cared for by their mothers and wives and by whom they are fed with food, exhorted and encouraged.[49]

Siege techniques Little is known or reported about the siege techniques of the ancient Germanic peoples. Living in small villages that, according to today's archaeological findings, do not appear to have been equipped with high, thick walls (as were the oppida of the neighboring Gauls), they knew no specific siege techniques, perhaps only some defensive techniques. A brief mention is made of a failed attempt by them to besiege a Roman post during the years of the Marcomannic wars. This episode is depicted in Scene XI of Marcus Aurelius' column in Rome, according to which the barbarians prepared a large siege machine that was destroyed by lightning. The episode is said to have been witnessed by the Emperor himself, Marcus Aurelius.[50] Also attributed to this period is another failure by the Germanic coalition of Marcomanni, Quadi and Vandals to besiege Aquileia (in 170): although the barbarian horde was very numerous, once again it proved powerless before the walls of a large Roman city.[51] The first sieges of any significance to Roman cities, which lasted for a long time and in some cases were successful, would belong to the mid-3rd century, when the northern barbarians began to repeatedly break through the Roman limes. It is said that in 248 the Goths were stopped by Philip the Arab's general, Trajan Decius, future emperor, near the city of Marcianopolis, which had been under siege for a long time. The surrender was made possible by a still rudimentary technique on the part of the Germani in the form of siege machinery and probably, as Jordanes suggests, "by the sum paid to them by the inhabitants."[52] Again in 249, a new wave of Goths and Carpi besieged Philippopolis (today's Plovdiv) for a long time, where the governor Titus Julius Priscus was located.[53] A decade later, in 260, hordes of Franks succeeded in seizing the legionary fortress of Castra Vetera and besieged Cologne, sparing Augusta Treverorum (today's Trier) instead.[54] In 262, again the Goths carried out a new sea raid along the Black Sea coast, managing to sack Byzantium, ancient Ilium and Ephesus.[55]

Ambushes The great forests and immense swampy areas of Germania Magna[56] enabled these ancient peoples to implement increasingly effectively, against the Roman advance into their territories, the tactic of ambush. The most famous one remains the one implemented by the prince of the Cherusci, Arminius, who near the modern site of Kalkrieser managed to completely destroy an entire Roman army, consisting of three legions, 6 infantry cohorts and 3 wings of auxiliary cavalry. Based on recent excavations of the battle site, modern historians and archaeologists have come to the conclusion that Arminius had very carefully arranged all the details of the ambush:

This is the description handed down to us by the historian Cassius Dio of the initial Germanic assault on the marching Roman "column":

Other ancient Roman historians portrayed this massacre as one of the worst in the entire Roman history, comparable only to Cannae and Carrhae:

However, this was not the only episode. Other incidents are recorded of other Roman generals who, through luck and tactical skill, managed to emerge victorious, such as Drusus the Elder during the military "campaign" of 12-9 BC, when he fell into very dangerous pitfalls during a retreat:

Other incidents include those of Aulus Caecina Severus during the Germanicus expedition of A.D. 14-16;[57] or again during the Marcomannic wars, in the so-called "miracle of the rain" episode, when a Roman "column" trapped among the forests and mountains of Marcomannia was saved by rain, which quenched the thirst of the Roman soldiers, surrounded by the Quadi, giving them renewed energy to emerge victorious from the Germanic encirclement.[58] Cavalry combatCaesar describes the equestrian fighting of the Germani in his Book IV of De bello Gallico (55 B.C.):

Tacitus, a century and a half later, adds more detail to the cavalry units, arguing that their horses were neither beautiful to look at nor fast in riding. The Germani did not teach them to perform maneuvers, as the Romans did. They either rode them straight ahead, or made them fall back with one type of turn to the right, so that they would not hinder each other in the event of a retreat, thus preventing anyone from falling behind.[44]  Raids and incursionsIn Caesar's time, raids carried out outside one's territory did not bring infamy. On the contrary, they were said to represent a way to discipline the youth and diminish laziness and cowardice.[59] AuguriesThe Germani drew auguries in order to predict the outcome of important wars, by having a prisoner belonging to that particular enemy fight one of their champions. Each of the combatants then made use of their own weapons. The victory of either one or the other was regarded as an omen.[60] StrategyEach people considers it the greatest glory to have around the borders of their nation uninhabited territories for the largest possible extent. This means for them that a number of nations is unable to resist their force of arms. Caesar relates that one side of the Suebi borders is uninhabited for a stretch of country equal to about 600,000 passes (equal to just under 900 km).[61]

Size of armiesCaesar recounts in his De bello Gallico that the people of the Suebi, to which Ariovistus belonged, were by far the most numerous and warlike of all the Germanic peoples, and could field to wage war outside the borders of their territories as many as 100,000 armed men (1,000 for each pagus).[62] The coalition of Germanic peoples,[6] which consisted of Marcomanni, Triboci, Nemetes, Vangiones, Sedusi, Suebi and Harudes, seems to have grown to between 100,000 and 120,000 rapidly.[8] A few years later (in 55 B.C.E.), Caesar again recounts a new incursion into Gaul by the Germanic tribes of Usipetes and Tencteri, who had pushed out of their territories, north of the Main River, and reached the regions inhabited by the Menapii at the mouth of the Rhine. Caesar claims there were as many as 430,000 people, including civilians and armed men.[63] It is said that Prince Maroboduus, king of the Marcomanni of Bohemia, against whom the Roman general Tiberius had deployed his armies in an expedition that was never completed in 6 CE, had a large army:

In 9 A.D., the prince of the Cherusci, Arminius, succeeded in assembling a coalition of Germanic peoples consisting of Cherusci and Bructeri, as well as probably Sicambri, Usipetes, Marsi, Chamavi, Angrivarii and Catti, totaling an estimated 20,000 to 25,000 armed men.[64] Regarding the large forces that the Germani fielded during the invasions of the third century, they can be summarized as follows:

See alsoReferences

Bibliography

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Portal di Ensiklopedia Dunia