|

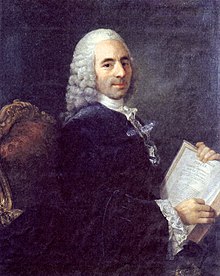

Louis XV