|

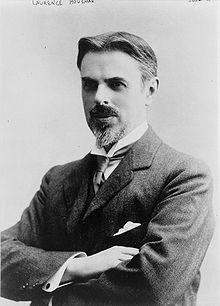

Laurence Housman

Laurence Housman (/ˈhaʊsmən/; 18 July 1865 – 20 February 1959) was an English playwright, writer and illustrator whose career stretched from the 1890s to the 1950s. He studied art in London and worked largely as an illustrator during the first years of his career, before shifting focus to writing. He was a younger brother of the poet A. E. Housman and his sister and fellow activist in the women's suffrage movement was writer/illustrator Clemence Housman.[1] Early lifeLaurence Housman was born in Bromsgrove, Worcestershire to Edward Housman, a solicitor and tax accountant, and Sarah Jane Housman (née Williams).[2] He was one of seven children including an older brother and sister, the classical scholar and poet Alfred E. Housman and the writer and engraver Clemence Housman. In 1871 his mother died, and his father remarried to a cousin, Lucy Housman. Under the influence of their eldest brother, Alfred, Housman and his siblings enjoyed many creative pastimes amongst themselves, including poetry competitions, theatrical performances and a family magazine.[3] The Housmans suffered increasing financial distress as Edward’s business floundered and he succumbed to drinking and illnesses. Despite this, Housman and his brothers managed to receive an education at Bromsgrove School on scholarships. He and his sister Clemence attended a local art class in 1882, and in 1883 they each received a £200 inheritance, which they used to go to study art at the Lambeth School of Art and the Royal College of Art in London.[4] IllustratingHe first worked with London publishers by illustrating such works as George Meredith's Jump to Glory Jane (1892), Jonas Lie's Weird Tales (1892), Christina Rossetti's Goblin Market (1893), Jane Barlow's The End of Elfintown (1894) and his sister's novella The Were-Wolf (1896)[5][6] in an intricate Art Nouveau style. During this period, he also wrote and published several volumes of poetry and a number of hymns and carols.[7] Writing Housman turned more and more to writing after his eyesight began to fail. His first literary success came with the novel An Englishwoman's Love-letters (1900), published anonymously. He then turned to drama with Bethlehem (1902) and was to become best known and remembered as a playwright. His other dramatic works include Angels and Ministers[8] (1921), Little Plays of St. Francis (1922) and Victoria Regina (1934) which was even staged on Broadway. Housman's play, Pains and Penalties, about Queen Caroline, was produced by Edith Craig and the Pioneer Players.[9] Some of Housman's plays were scandalous for depicting biblical characters and living members of the Royal House on stage, and many of them were performed only privately until the subsequent relaxation of theatrical censorship. In 1937 the Lord Chamberlain ruled that no British sovereign may be portrayed on the stage until 100 years after his or her accession. For this reason, Victoria Regina could not be staged until the centenary of Queen Victoria's accession, 20 June 1937. This was a Sunday, so the premiere took place the next day.[10] Housman also wrote children's fairy tales such as A Farm in Fairyland (1894) and fantasy stories with Christian undertones for adults, such as All-Fellows (1896), The Cloak of Friendship (1905), and Gods and Their Makers (1897).[11] A prolific writer with around a hundred published works to his name, his output eventually covered all kinds of literature from socialist and pacifist pamphlets to children's stories. He wrote an autobiography, The Unexpected Years (1937), which, despite his record of controversial writing, said little about his homosexuality, the practice of which was then illegal.[12] After his brother's A.E.'s death in 1936, Laurence was made literary executor, and over the next two years brought out further selections of poems from his brother's manuscripts. His editorial work has been deprecated recently: "The text of many poems was misrepresented: poems not completed by Housman were printed as though complete; versions he cancelled were reinstated; separate texts were conflated; and many poems were mistranscribed from the manuscripts."[13] ActivismSuffrage movementLaurence Housman identified himself as a feminist, contributing mainly to the Suffrage movement in England. His activism was largely through works of art such as creating banners, creating propaganda, writing and contributing to women's newspapers. However, he also participated in physical protests, frequently speaking at suffrage rallies. He took part in handing in a petition against force feeding, and was arrested during associated disturbances.[14] The Suffrage Atelier Laurence Housman and his sister, Clemence Housman, founded the Suffrage Atelier in February 1909.[15] This was a studio that produced artistic propaganda for the suffrage movement. The studio was located at his house, No. 1 Pembroke Cottage Kensington.[16] Although there were other studios throughout England also creating propaganda for the suffrage movement such as the Artists’ Suffrage League and the Women’s Social and Political Union, the Suffrage Atelier was unique because they paid their artists by selling the work to the suffrage community.[16] This studio was important not only in creating propaganda for the suffrage movement but because the creation of banners required collective work. This was significant as it created an environment for women to find other women.[16] Additionally, work such as embroidery, which was known to be domestic, was utilized to propel a political movement and allowed women to earn money.[16] No. 1 Pembroke Cottage KensingtonAside from his Suffrage Atelier studio, Housman opened his house to the suffrage movement and it quickly became a hub for the feminist movement.[16] Along with housing the Suffrage Atelier studio, it additionally held educational classes to help women explore their feminist identities, bringing in public speakers and hosting writing lessons.[16] The house was also used as a safe house on the night of the 1911 census, protecting women participating in the organized Census Boycott.[16] Art and designThe Anti-Suffrage Alphabet was a book designed by Housman that incorporated illustrations from several women, including Alice B. Woodward and Pamela Colman Smith,[17] which worked to raise funds for the suffrage campaign.[18] The main goal of the book was to criticize women’s disenfranchisement by mocking negative attitudes towards women.[17] "From Prison to Citizenship" was the first banner created by Housman as a contribution to the Women’s Social and Political Union.[15] This banner was displayed at the Queen’s hall at an unveiling ceremony and has been used regularly by the Women’s Social and Political Union.[15]  WritingHousman incorporated his passion for writing in his work with the feminist movement. He was popular for taking other people’s work and giving it a feminist twist.[15] For example, he read “Tommy this Tommy that” by Rudyard Kipling as “Women this Women that” at a Hype Park rally.[19] He also contributed to newspapers, advising women on how to protest; his advice can be found in the Women’s Freedom League.[20] Additionally, a series of poems supporting the Suffragette movement was published in The Women’s Press as well as Votes for Women.[20] In 1911 the Census Boycott, a feminist movement with the goal of disrupting government processes, asked women to refuse to give their information for the census.[21] The movement was advertised by Housman through a series of articles published in The Vote, in which he argued for the reasoning and tactical benefits of the proposal.[22] He also wrote fiction supporting the movement, setting this series in a potential future where the boycott went well.[22] Men’s League for Women’s Suffrage Housman believed men should be an active participant of the suffrage movement. Therefore, Housman along with Israel Zangwill, Henry Nevinson and Henry Brailsford formed the Men’s League for Women’s Suffrage to propel the movement.[23] These four writers were able to successfully convince some men in the 1910 general election to write Vote for Women on their ballot.[23] He was also active in another male feminist group, the Men’s Social and Political Union.[19] Economic beliefsHousman thought economics was a central component working to oppress women. He believed the Suffragettes perceived masculinity to value market values while feminine values leaned to be more utopian and reflect collective values.[24] The Suffrage movement, therefore, centred maternal values, de-individualizing the movement.[24] This, was important as it helped break the stereotype that women, especially mothers, who were active in the movement, were bad citizens.[24] Other activismHumanist movementAn atheist, Housman was a leading light of the British Ethical and humanist movements in his lifetime. A Vice President of the Ethical Union (today known as Humanists UK), "Housman's humanism was active and lifelong, evidenced by his myriad efforts towards equality and social reform, guided by reason and compassion," to which he donated 40 years of activism. In 1929, he also gave the Conway Hall Memorial Lecture on the topic of ‘The Religious Advance Towards Rationalism’ (using "religious" in the sense of "organised", as in "religious humanism").[25] Housman attributed his own loss of faith and adoption of humanist beliefs to his strict Victorian upbringing. He said: "It was this sanction of obscurantism... which started the breach between myself and the narrow Conservatism of my upbringing. I could not feel that any social or religious system, which so sedulously refused to tell and to face the truth, deserved respect; and though for a while I still conformed, it was without heart or conviction."[25] Later he opined that many in the Victorian era conformed to Christianity in name only, while acting on "worldly" convictions of right and wrong: "One hears a good deal of talk nowadays about the decay of religion; and the Victorian age is spoken of as though it had been an age of faith. My own impression of it is that it combined much foolish superstition with a smug adaptation of Christianity to social convention and worldly ends."[25] His sexualityHousman was openly homosexual and invested himself to help other homosexuals to be less stigmatized by society. To do so, he joined an organization called the Order of Chaeronea which was a secret society that worked to gain homosexuals social recognition.[26] Additionally, he also was a founder of the British Society for the Study of Sex Psychology.[19] This was an organization which aimed to advance sex reform hoping for a more open society regarding sexualities by breaking prejudices.[27] It was originally known as the British Society of Psychiatry; however, Housman wanted it known as a society and had it changed.[27] Housman also brought his artistic contributions to the fight of de-stigmatizing homosexuality. For example, he created pamphlets for the organization such as The Relation of Fellow-Feeling to Sex.[27] Peace Pledge UnionIn 1945 he opened Housmans Bookshop in Shaftesbury Avenue, London, founded in his honour by the Peace Pledge Union, of which he was a sponsor. In 1959, shortly after his death, the shop moved to Caledonian Road, where it is still a source of literature on pacifism and other radical approaches to living.[28] Later lifeAfter World War I, Laurence and Clemence left their Kensington home and moved to the holiday cottage which they had previously rented in the village of Ashley in Hampshire.[29][30] They lived there until 1924,[31] when they moved to Street, Somerset, where Laurence lived the last 35 years of his life.[32] Posthumous recognitionHis name and picture (and those of 58 other women's suffrage supporters) are on the plinth of the statue of Millicent Fawcett in Parliament Square, London, unveiled in 2018.[33][34][35] CollectionsUniversity College London holds c.450 volumes of Housman's works. The collection formed part of the holdings of Ian Kenyur-Hodgkins, an antiquarian bookseller whose material was purchased by the University in 1978.[36] The Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas holds an archive of Housman's material which includes manuscripts and correspondence.[37] Published writingsSource: Open Library list of his works.[38]

Novels

Short fiction

Plays

Verse

Translation

Non-fiction

Works edited

References

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Laurence Housman.

|

||||||||||||||

Portal di Ensiklopedia Dunia